- Author

- Issacs, Keith, AFC, ARAeS, Group Captain, RAAF (Retd)

- Subjects

- History - WW1, Naval Aviation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Melbourne I, HMAS Sydney I, HMAS Australia I

- Publication

- March 1974 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

In the third part of his story on Australian Naval Aviation, Group Captain Isaacs discusses the merits of the Sopwith Ship’s Strutter and the Sopwith Ship’s Camel, aircraft that played a pioneering role in naval aviation.

Sopwith Ships Strutter

The Sopwith 1½ Strutter as used by the Royal Flying Corps and No. 6 (Training) Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, has already been described. This biplane had at least four official titles – the Sopwith Two- Seater for the Royal Flying Corps, the Sopwith Type 9400 two-seater and Type 9700 single-seater for the naval land-based squadrons and, when relegated to shipboard use, the Sopwith Ship’s Strutter. But as usually happened, the popular nickname caught on and the aircraft was universally known as the 1½ Strutter, or simply Strutter.

The Strutter was first developed in 1915 for the Royal Naval Air Service. In the early months of 1916 Strutters of No. 3 Wing at Luxeuil were formed into a strike force to carry out some of the first planned strategic bombing raids in air warfare history. The targets were the industrial centres of Germany, and the bombers were built as single-seaters carrying up to 12 bombs stowed internally. Although the forward-firing synchronised machine-gun for the pilot was retained, the observer’s cockpit was eliminated to compensate for the bomb load. This perturbed an Australian, Sidney Cotton, who was serving with the Royal Naval Air Service at the time. Cotton not only missed the comradeship of his observer, but more importantly the protection he offered. So Cotton ingenuity came to the fore:

‘I fitted a gun-ring to my plane immediately behind the cockpit (he explained later), and painted a large black blob at the point along the fuselage where the gunner sat in the fighter version, to fool the Germans into thinking that my bomber was a fighter. They held the fighter version in great respect, and they seldom attacked a bomber if it was accompanied by a fighter. I also fitted a Lewis gun behind my back firing backwards, and I fitted the trays with tracer bullets to make sure that anyone who got on my tail knew it was firing. We were trained to fly in V formation and I always took up position at the tail-end of the V. Any fighter coming into attack would suddenly see tracer bullets coming at him and would think – or so I hoped – that there was a fighter guarding the rear.’

Of about 550 Strutters used by the Royal Naval Air Service, some 420 were two-seaters and the remainder single-seaters. They were used during 1916 in attacks against Zeppelin sheds, enemy aerodromes, ammunition dumps, and U-boat bases. When the aircraft’s performance became obsolescent in 1917 some naval Strutters were transferred for overseas service to Macedonia and the Mediterranean area.

During the latter part of 1917, launching experiments from ships were carried out with single-seat Sopwith Pups and Camels, which were considered ideal types for the protection of the fleet from air attacks. The landplane scout was preferred to the seaplane because of better performance in climb and speed, two necessary requirements for the interception of Zeppelins. What was needed next was some reliable method of launching a two-seat aircraft at sea to meet the fleet’s requirements for aerial reconnaissance. There were two schools of thought on how this could be done, either from carriers or from the decks of warships. Both approaches were taken to their logical conclusions, and the flagship of the Royal Australian Navy played an important part in the latter experiments.

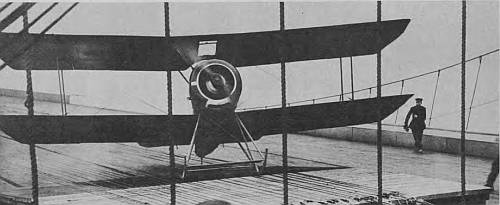

The British Official History described how ‘. . . the turret platform in the Repulse was extended but an attempt in a Sopwith 1½ Strutter in March 1918 failed. Trials were then transferred to HMAS Australia where a bigger platform was built . . .’ The ill-fated launching experiment from Repulse must have occurred in the first days of March because the Australian Official Historian, referring to Australia, recorded that ‘on the 8th of March 1918 a two-seater seaplane was successfully launched from a short deck constructed on a turret and prolonged over the chase of the turret-guns, and another successful flight was made on the 14th of May.’

The generalisation of terms as used by Jose does not, however, give a clear picture. His reference to a ‘seaplane’ appears ambiguous, because landplanes only were used in these particular launching trials, and he was probably referring to Australia’s 1½ Strutter, a landplane being operated at sea. This aircraft is shown in a much published photograph (IWM Q.18729 and AWM EN.343 and EN.544) taking off from a ramp over the 12 inch guns on the amidships starboard ‘Q’ turret while Australia was at Rosyth. It is believed that the pilot on this occasion, 8 March 1918, was Flight Sub- Lieutenant Simonson – he is shown flying solo from the anchored Australia and the turret is turned into a strong wind, as is evident from the flags flying on HMS New Zealand in the background. The official caption for the Imperial War Museum photograph stated merely ‘HMAS Australia. Sopwith 1½ Strutter flying from platform built upon a turret,’ while the Australian War memorial caption – ‘An aeroplane starting on a trial flight from HMAS Australia in harbour, Rosyth, Scotland, in December 1918′ – appears to be wrongly dated because Australia at that stage was carrying the Ship’s Strutter, F.7562, which was produced later than the aircraft shown in the photograph.