- Author

- Ellis, John

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Voyager I

- Publication

- September 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By John Ellis

This article first appeared in the United Service Journal 65(1) March 2014 and is reproduced with the kind permission of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales.

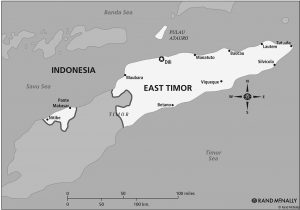

Earlier this year (2013) I accompanied a group of Rotarians to Dili, East Timor, to implement a youth leadership training programme. There was an opportunity to visit Betano Bay, the scene of tragedy for HMAS Voyager in September 1942 and I was curious to see if any remains of Voyager might be still visible and whether the incident and other events of that time remain with local minds.

Sparrow Force

With Japan’s entry into World War II, landing in Malaya on 8 December 1941, Dutch colonies in South East Asia were threatened. On 10 December 1941 Australia deployed a force of 1,400 troops from the 8th Division from Darwin in SS Zealandia to Koepang (now Kupang) in Dutch Timor. They travelled under the name of Sparrow Force. On landing, the force was divided and 2/2nd Independent Company moved to Dili in Portuguese Timor. Portugal’s policy of neutrality was the official line in Dili, however many local authorities realised such a view would probably be deemed of little consequence by the Japanese. Reinforcements were despatched in mid Janaury 1942; the convoy, protected by HMA Ships Swan and Warrego, retreated to Darwin on encountering superior enemy air power. The reinforcements were eventually landed on 12 February. A week later, the success of the Japanese attack on Darwin saw Sparrow Force isolated in Timor. A day after the attack on Darwin, the Japanese landed at Koepang and after four days their superior numbers secured the capitulation of the force of 1,100 Australians on 23 February. A similar attack on Dili was resisted by the Independent Company before they melted away into the rugged hinterland.

There was no further word from the Independent Company for two months, when faint radio messages were picked up in Darwin. This company, trained in guerilla tactics at Wilsons Promontory, Victoria, was able to contain the Japanese in Portuguese Timor for another 12 months. Their success in distracting a Japanese divison for a year could not have been achieved without the support of local Timorese, who risked execution by the Japanese. Indeed, Japanese policy throughout the East Indies was to encourage locals to take the opporunity of shedding the European yoke. In late April 1942, the survival of the Indpendent Company in Timor was relayed to Darwin via weak signals from an improvised radio set, dubbed ‘Winnnie the War Winner’. Within a few days, much needed supplies were parachuted in. Initially they were supported by random drops from Darwin-based Hudson bombers. In late May and early June, HMAS Kuru made the first two of six voyages to land stores and men. Kuru was a motor launch, 23 m long, capable of 13 knots, armed with a 20 mm Oerlikon and a machine gun. In July, HMAS Vigilant added further support. She was a requisitioned Customs vessel, 30 m long, capable of 14 knots. The minesweeper HMAS Kalgoorlie, joined the support in September 1942. These ships used Suai and Betano Bay on the south coast of Portuguese Timor to land their men and supplies.

HMAS Voyager

By June 1942, Army Headquarters was planning to relieve the 2/2nd Independent Company with the 2/4th Independent Company. A larger, faster ship was required and the task fell to Voyager. She had established a proud record in the Mediterranean in 1940-41 under the command of Lieutenant Commander J.C. Morrow, DSO, RAN, and she returned to Sydney for refit in September 1941. She was back at sea in March 1942 under the command of Lieutenant Commander R.C. Robison, DSC, RAN. He had been decorated when First Lieutenant of HMAS Stuart at the Battle of Matapan. Following her refit, Voyager was engaged in escort duties around southern and western coastal waters of Australia until despatched to Darwin in mid September 1942. There she embarked 250 troops, 15 tonnes of stores and eight army barges; she sailed for Betano Bay on 22 September. This shallowly-indented bay is some two and a half miles across; the bay is steep, with deep water close to the beach. There are many reefs at the eastern end of the bay and there were no markers ashore. Robison’s aids to navigation were his echo sounder, lead line, a rough sketch of Betano Bay without soundings, and Sub Lieutenant H. A.Bennett, RANR, who had commanded Kuru and Vigilant.

The coast of Timor was sighted late next day and at 1823 Voyager was steaming slow ahead into Betano Bay. The echo sounder recorded 128 fathoms followed closely by 25 fathoms when about seven cables off the beach. At 1828 Robison anchored two and a half cables off the beach. Disembarkation of the troops commenced a minute later. The ship’s whaler was lowered and took soundings around the ship. Five minutes later, the ship had swung and was closing the beach. Robison could see he needed to weigh and shift to deeper water. He wanted to go astern on the port engine and ahead on the starboard to get his stern out into deeper water. There were, however, two barges loaded with troops on the port quarter. The soldiers could not grasp the dangers of the situation and did not respond to urgent demands from the bridge to move out of the way. Robison’s desired course would have upset the barges, and his solution was to turn to starboard and proceed ahead. For 16 minutes Robison manoeuvred his ship slowly on his starboard engine.

At 1850, with ‘Half ahead both, starboard 20,’ Voyager’s stern was aground. Efforts to free the ship continued through the night until noon the next day. Despite laying a kedge anchor and jettisoning depth charges, torpedoes and heavy weights, she was fast, her screws under the sand. A reconnaisance aircraft, with a Zero as escort, appeared at 1330 and was shot down by Voyager’s guns. Robison realised their presence was now known and ordered the ship be scuttled. At 1600, three bombers and two fighters appeared. Robison signalled Darwin and Voyager’s company was rescued by HMA Ships Kalgoorlie and Warrnambool four days after the grounding. The stricken ship was photographed at the time and again shortly after the peace in 1945, when remains of an identifiable ship were still visible on the beach.

Today, the remains of boilers and engines can be seen only at low water. These remains were located in November 1999 by the Hydrographic Office Detached Survey Unit following their main task of the pre-landing survey for the INTERFET operations. The image was taken by LCDR D.J. Perryman, RAN, then attached to INTERFET. On my visit in August 2013, discussion with local fishermen indicated the remains of Voyager and her significance were still well known.

The Fate of Sparrow Force

What of Sparrow Force? The 2/2nd Independent Company, reinforced in September, continued to conduct raids on the Japanese. By November 1942, the Japanese were gaining the upper hand and Australia decided to withdraw. An early evacuation saw HMA Ships Castlemaine and Armidale at Betano Bay. In this operation Armidale was lost with very few survivors. The bulk of the Australian troops were evacuated in HMAS Arunta under the command of Commander J.C. Morrow. The last of the Australian troops were brought out in February 1943. Sparrow Force lost 151 in Dutch and Portuguese Timor.

Arunta’s evacuation included Major Bernard Callinan, whose extraordinary leadership in Timor was recognised with the award of the Military Cross. On his return to Australia he was promoted and was later awarded the Distinguished Service Order for leadership in New Guinea. In later life, his civil engineering background saw him as chief executive officer of Gutteridge, Haskins and Davey with the award of a knighthood, Commander of the British Empire and Companion of the Order of Australia recognising his contribution to engineering in Australia.

Retribution by the Japanese on the local people of what is now East Timor (Timor-Leste) was severe. It is estimated at least 40,000 perished, possibly as many as 70,000. Further grief for East Timor followed during Indonesian rule between 1974 and 1999. At least a third of the population perished, either at the hands of the Indonesain militia or illness and starvation arising out of Indonesian policies. During this period we and others looked away until Prime Minister Howard responded to the events surounding the independence referendum in East Timor in 1999. The achievements of Sparrow Force in Timor are recognised at the Dare Memorial, some 15 km along a tortuous and appalling road from Dili, although only 4 km as the crow flies. The memorial includes a photograph of Voyager soon after her grounding. Dare (pronounced dar ray) was a vantage lookout across to the Japanese based in Dili.

Further Reading:

Callinan, Bernard J. (1953). Independent Company: the 2/2 and 2/4 Independent Companies in Potuguese Timor, 1941–1943 (Heinemann: London) (Ursula Davidson Library call number: 588 CALL 1953).