- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Fairlie Clifton

Much of the modern history of Australia and New Zealand arises from the discoveries of James Cook and his fine ship Endeavour. For this reason Endeavour is of national importance, which is encapsulated in her Australian built replica, launched in December 1993. But what happened to the original ship is a mystery which has eluded historical research for more than two centuries. Recent announcements on her possible fate are therefore of significant interest.

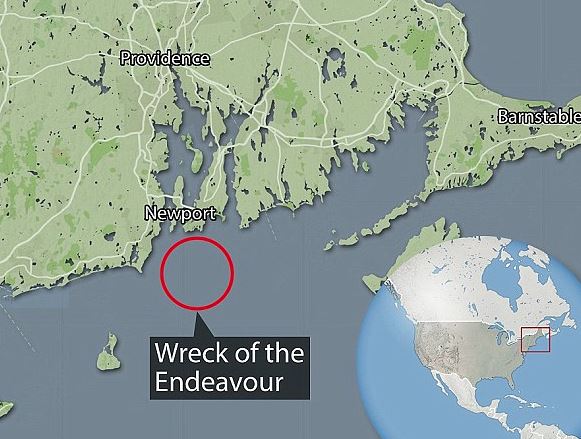

At a press conference on 3 February 2022 the outgoing Chief Executive Officer of the Australian National Maritime Museum, Kevin Sumption, declared that the remains of Captain Cook’s ship Endeavour had been discovered off Newport, Rhode Island. Saying: ‘This is an important moment. It is arguably one of the most important vessels in our maritime history’ and ‘We can conclusively confirm that this is indeed the wreck of Cook’s Endeavour’.

Background

This famous ship started life in 1764 as the North Sea collier Earl of Pembroke. Four years later she was purchased by the Admiralty for a scientific mission to the South Pacific and to search for the ‘Unknown Southern Land’. Commissioned as His Majesty’s Bark Endeavour, she departed Plymouth in August 1768 under the command of Lieutenant James Cook RN.

Following Cook’s famous voyage of discovery, she returned to the southern English port of Dover on 12 July 1771. Refitted, she was largely forgotten and made three return voyages to the Falkland Islands to resupply the British garrison there. The last voyage, in April 1774, evacuated the garrison.

She decommissioned in September 1774, was sold out of service, and renamed Lord Sandwich. This renaming in a small way re-established her connection with Cook, as Lord Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty in the latter half of the 18th century, was an keen supporter of Cook’s voyages. She then transported timber from the Baltic before being contracted by the British Government in 1776 as a troop transport to take British and Hessian troops to fight against American independence-seeking colonists. The Hessians were German mercenaries who fought with the British Army. Up to 30,000 such troops were used during the American Revolutionary War, representing a quarter of British land forces. This use of mercenaries outraged the colonists.

How did Lord Sandwich come to be in Newport, Rhode Island?

In May 1776, with over 200 Hessians on board, the ship joined a fleet of 100 ships (nearly 70 were transports) which left Portsmouth for New York. After a very rough crossing the fleet reassembled at Halifax, Nova Scotia before moving on to New York, which was successfully captured from the Americans.

The British then turned their attention to Newport, which was held by American forces and was a threat to New York. Lord Sandwich, with another contingent of Hessians on board, joined the fleet bound for Newport, which was swiftly taken.

In 1777 France joined the war on the side of the Americans, and in the summer of 1778 these allies launched a combined assault on Newport. This involved the Continental Army and French forces approaching from the north, and a French naval bombardment from the harbour. To block French access to the Inner Harbor the British burned frigates and scuttled 13 transports in the Outer Harbor. Lord Sandwich, by now in use as a low value hulk housing American POWs, was one of the thirteen.

The British managed to retain control of Newport, and some of the scuttled transports were re-floated. The wrecks of those that remained lay gently rotting away being covered with silt, with bits and pieces secured by souvenir hunters, and their exact location being forgotten in the mists of time.

The search for HMB Endeavour

In 1998 two Australian historians, Mike Connell and Des Liddy, established the connection between Endeavour and Lord Sandwich via their archival research. Their work was expanded by the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project (RIMAP) headed by Dr Kathy Abass. RIMAP is a not-for-profit organisation established in 1993, with interests in Rhode Island’s rich maritime history and marine archaeology. Its goals are to locate, identify and protect the submerged cultural resources of Rhode Island waters.

In 1999 collaboration between the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) and RIMAP began, with the aim of determining if Lord Sandwich was one of the 13 scuttled ships. An agreement between the two was signed, and criteria that would have to be met for positive identification were developed. It was agreed that any eventual identification should be based on a ‘preponderance of evidence’ approach. These criteria were reconfirmed by ANMM and RIMAP in 2018.

Unfortunately, after five years of joint work in a very large area of interest in the northern summer months of 1999-2004, the dive teams failed to find any evidence. Work resumed in 2015, with diver surveys of a large area of Newport Harbor’s seafloor. Then, in 2016, there was a wonderful breakthrough.

Dr Nigel Erskine, ANMM’s Head of Research, using remarkable detective work and scouring Admiralty records and 250-year-old British shipping logs at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, located two letters from August 1778 concerning the scuttling of five transports, including Lord Sandwich. In the first letter John Brisbane, Newport naval commander, ordered John Knowles, agent for transports, to scuttle the transports, including Lord Sandwich. Knowles’s response when this had been done included the locations of the scuttled ships in the narrow channel between Goat Island and the North Battery at Newport, as well as details of each

ship which showed that Lord Sandwich was by far the largest of the five. Dr Erskine’s research enabled the search partners to focus on a far smaller search area.

In 2017 marine archaeologist Dr James Hunter joined the team – Kieran Hostie of ANMM, and RIMAP volunteers – and began conducting 3D photogrammetry of the five transport sites. Using this technology and researching Lloyd’s Shipping Register for dimensions, tonnages and key dates, then cross-checking against the team’s underwater surveys, resulted in profiles of each ship. The Lord Sandwich wreck clearly stood out. A digital model of it from the surveys was superimposed on the Endeavour’s 1768 Admiralty plans (those from which the replica was built) and there was a near perfect fit. This was a magical moment.

In 2019 with marine archaeologist Irini Malliaros from the Silentworld Foundation joining the ANMM-RIMAP team, a more comprehensive survey of the largest vessel was conducted and permission was given by the Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission (RIHPC) for timber samples to be taken for analysis. Permission was also given for limited excavation of the site.

Early in 2020 the stump of a bilge pump shaft was uncovered and this provided an identifiable reference point within the hull. When the site plan of the wreck was superimposed on the 1768 plans, the locations of the pump shaft, pump well and centreline all aligned. The imagery also enabled the team to predict the location of the wreck’s bow and stern. With further excavation and knowing the likely wind direction in August 1768, the bow was found in its predicted location. A remarkably well-preserved scarph (or joint) was also located where it attached to the stem. This type of scarph is very rare in 18th century ships, and the size and form of this one corresponded exactly with the 1768 Admiralty plans.

Groupings of three floor timbers at midships and a set of paired floor timbers in the bow section also correlated exactly to the positions of Endeavour’s mainmast and foremast in the 1768 plans. Such groupings do not occur anywhere else within the recorded hull and are indicative of additional strengthening to support the two masts.

Further work was interrupted by the pandemic but went on remotely with, at the US end, respected American marine archaeologist Dr John Broadwater, specialising in 18th century ships, and remote sensing specialist, Joshua Daniel, representing ANMM. By September 2020 it had been determined that the wreck was that of a large, robustly built, flat-floored 18th century vessel with a keel constructed of European elm, a firm indication that the ship was British or European built. Other timber scantlings recorded were a close match with Admiralty survey reports when Endeavour entered Royal Navy service in 1768.

During 2021 the ANMM marine archaeology team reviewed the findings of the previous surveys. By 2022, using the preponderance of evidence approach and innovative technology, ANMM decided that sufficient of the identification criteria had been met to prove that the remains of Lord Sandwich were indeed those of Cook’s Endeavour.

Years of persistence, research and field work requiring great precision in very difficult conditions had finally paid off. The water in the channel where the five transports were scuttled is almost always very murky, with very poor visibility (averaging 1.5 m), and there is a great deal of sediment over the wreck at a depth of 13 m to contend with. As well, in the summer months when the work was being carried out, there is a lot of boat traffic, stirring the sediment. Work could only be done in the northern summer but some work was done in January 2020 (midwinter in Rhode Island) when the water temperature was around 2oC. Even in summer, the water temperature is low around Rhode Island.

On the basis of the ANMM/Silentworld team’s findings the ANMM Director, Kevin Sumption, announced on 3 February 2022 that HMB Endeavour had been found. RIMAC felt that this announcement was premature, believing that identification should await discovery and dating of artefacts found on the wreck site. However, the ANMM team contended that identification would depend upon the surviving hull. It was the team’s view that recovery of artefacts naming the ship, for example the ship’s bell or a sign, was most unlikely, given that the ship ended its life as a prison hulk from which anything of value would have been removed before scuttling. In its years of work on the site, ANMM did not find artefacts which would have aided identification.

What next?

There is now an urgent need to secure the wreck site at Newport, with the highest level of legislative and physical protection for such an important historical site. This will involve the government of the State of Rhode Island, which owns the wreck, the RIHPC, RIMAP and others.

ANMM is confident of its findings and has prepared a 100-page report which has been sent to RIMAP. Reports from RIMAP and the RIHPC are awaited. If ANMM’s findings in its report are disputed, ANMM would welcome another level of intensive peer review.

Meanwhile, ANMM is open to dialogue concerning its findings and is convening an online Endeavour Forum to take place in the near future, with marine archaeologists and scholars from the UK and elsewhere, including of course RIMAP and the RIHPC in Rhode Island, being invited.

In the meantime, work on the wreck site and liaison with the Rhode Island research partners is continuing. In his announcement in February Mr Sumption acknowledged the combined efforts of RIMAP and ANMM and paid tribute to the work of Dr Kathy Abass, Executive Director of RIMAP, and her team.

ANMM will continue to publish the work of its maritime archaeology team via its Deep Dive website. The following link relates to the finding Endeavour project – https://www.sea.museum/explore/maritime-archaeology/deep-dive/finding-endeavour

Acknowledgments:

ANMM Signals No. 138 Autumn 2022

ANMM Deep Dive website

RIMAP website