- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The late 19th century rumblings of colonial expansion to the immediate north of the Australian mainland gave rise to unease in the Australian colonies.Russian naval expeditions to the South Pacific also made our forefathers aware of their vulnerability to potential attack. The so called ‘Russian Scare’ gave rise to the improvement of fortifications in our main harbours. In 1871 the arrival of yet another Russian expedition in the waters to our north inflamed these fears. However the panic was soon allayed when it was realised that the mainstay of this expedition was one idealistic young man largely travelling at his mother’s expense.

Ian Fleming, a real life naval reserve officer, wrote the highly successful novel From Russia with Love, loosely based on his experiences as a naval intelligence agent. This gave rise to an exceptional film of the same name starring the fictional James Bond. More than a century before these events a debonair Bond-like character came to these shores. Was he idealistically intent on saving mankind or, was he a spy in the very midst of our society, reporting to Imperial Russian naval intelligence?

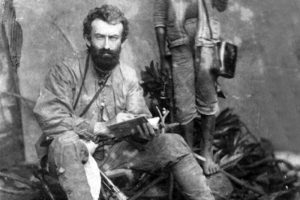

Enter Baron Nickolai Miklouho-Maclay (1846-1888) born the son of a hereditary Ukrainian nobleman and Russian mother; the quaint family name is due to an old Scottish connection. A more precise translation of the name is Mikukho-Maklai, however when living in Australia the scholar anglicised this to Miklouho-Maclay, which is used in this article and is sometimes shortened to Maclay.

Family background and early life

Nickolai’s father, a railway engineer, died when he was young leaving the burden of bringing up five children with his mother. She was a well read woman of progressive views, and during their early years, educated her children at home. During Nickolai’s youth Russia was experiencing unrest with many peasant uprisings marking the emergence of revolutionary democracy. At fifteen, when attending high school, the youngster was arrested and spent three days in prison for taking part in a student demonstration. In 1863 he gained entry to the prestigious St. Petersburg Imperial University, known for educating the country’s elite, but the next year was expelled for participating in student meetings – the situation must have been serious as he was deprived of the right to study at any other Russian institution of higher learning. Through family connections he finally obtained permission to complete his education in Germany.

Miklouho-Maclay entered the University of Heidelberg where he studied science, economics and philosophy. At this time he had mastered German, English and French. He again became imbued with radical views in the struggle to transform society through social equality. Maclay later transferred to the smaller University of Jena as a disciple of Ernst Haeckel, a major biologist and follower of Darwin. Maclay studied the mutability of organic forms relating to sea fauna. Haeckel, impressed by the bright young scholar, made him an Assistant and in 1886 took him on a voyage to Madeira, the Canaries and Morocco, after which Maclay wrote his first important scientific paper. On graduating from university he undertook another voyage to the coast of the Red Sea to further his zoological studies. On this journey he paid considerable attention to the living conditions of the local people and attempted to determine the reasons for their economic and cultural problems. In 1869 Maclay returned to St. Petersburg with excellent credentials and was accepted as a research assistant by the Zoological Museum and Academy of Sciences. Through his work here he developed an interest in marine zoology in the Pacific region.

The Imperial Russian Navy and Pacific exploration

An early Imperial Russian naval model for professional development and scientific endeavour was largely based upon their recognition of the eminence of Captain Cook as a commander and his scientific approach towards discovery. Within terms of their own expansion they saw improved knowledge of the Pacific as a means of exercising economic and strategic power. Somewhat like migratory birds Russian naval vessels in the 19th century regularly escaped the oncoming Baltic winter chills and headed south to their possessions in the Far East and the western shores of North America. As they followed their course from the Indian to the Pacific Ocean both Sydney and Hobart became ports of call where provisions were sought, repairs conducted and crews given shore leave.

The first of these calls occurred in 1807 when the warship Neva under command of the 26 year old Lieutenant Ludwig von Hagemeister arrived in Sydney during its circumnavigation. This was followed by numerous similar visits which became so common that their place of mooring near Neutral Bay became known as Russian Point. The most important of these occurred in 1820 with the Antarctic research and discovery conducted by Captain Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen in the sloop Vostokwhen twice using Sydney as a base.

By the late 1830s the previous good relationship between Britain and Russia had deteriorated as expansion of Russian influence was seen to be competing with Britain’s imperialistic ambitions. This antipathy extended to the Colony of New South Wales, which in 1841 established harbour fortifications to defend itself against an invasion – the only potential enemy was Russia! The Gold Rush and Crimean War tended to cement this adversity.

Friendlier relationships began to develop after the Crimean War with an inflow of Russian-speaking immigrants and Honorary Russian Consuls were established in 1857. In 1862 when HMIRS Sveltana sailed into Port Phillip Bay no powder was available to return her salute – causing angst and embarrassment. Rear Admiral Andrey Alexandrovich Popov, the commander of the Russian Pacific Squadron, flying his flag in HIMS Bogatyr, called at Sydney and Melbourne in 1863. While the visit was a success, when it was later reported that the Russian had conducted topographical surveys and inspected coastal fortifications, this again led to speculation of invasion with calls for improvements to defence capabilities. Finally in 1870 the corvette Boyarinappeared unexpectedly in the Derwent River raising fears that Hobart was about to be attacked. However her arrival was innocent as one of her officers was seriously ill and needed hospitalisation – he later died ashore and was buried with due ceremony in Hobart. Local funds were donated for a headstone to his grave, and in gratitude Captain Serkov presented the city with two mortars from his ship, which still stand at the entrance to Anglesea Barracks.

The above chronology brings us up to date with the arrival of Baron Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay in 1871. In many respects Creswell and other self defence advocates should be forever thankful for the assistance given to their cause by these friendly, if sometimes unexpected, Russian guests.

Arrival of Baron Nikolai Miklouho-Maclay

During the time of his theoretical research at the Academy of Sciences Maclay’s attention was drawn to New Guinea as a promising new field for anthropological and ethnological studies. Here he hoped to find primitive tribes unaffected by others that have risen to a comparatively higher status of civilisation. He was attempting to continue Darwin’s researches and establish beyond doubt that there was no difference between man regardless of origins, and that all mankind descended from one source.

Aided by the Imperial Geographical Society he was given a small grant and secured a place in the steam corvette Vitiaz which wasthen making a research voyage to the South Pacific. The President of the Geographical Society was Grand Duke Constantine Nikolayevitch, the second son of Tsar Nicholas I, also an Admiral of the Russian Fleet. Knowing that Maclay intended to live with the natives of New Guinea the Admiral promised to send other support vessels to check upon the young explorer’s progress – he generously lived up to these promises.

After a lengthy voyage from the Baltic via Cape Horn the ship anchored on the north-east coast of New Guinea at Astrolabe Bay (near present day Madang) on 20 September 1871. Astrolabe Bay was named after his ship in 1827 by the French navigator Durmount d’Urville but he never set foot ashore here. The Russians remained for a few days to establish a temporary observation post and Maclay, plus two assistants he had acquired during the voyage, were put ashore. A party from Vitiazraised the Russian flag and afterwards this was flown above Maclay’s residence, providing evidence of a potential Russian claim to sovereignty. Maclay also flew a Russian naval ensign from a boat he had acquired.

From these primitive beginnings commenced his odyssey which with patience, courage and medical skill Maclay won the confidence and co-operation of the inhabitants. He studied the people, their language and characteristics. He was the first European to set foot upon this rugged terrain and visit many isolated villages where he collected specimens, and as an accomplished graphic artist, drew the likeness of the people, flora and fauna and scenery. He also named the main features of what became known as the Maclay Coast.

The Russian frigate Izumrud called in December 1872 and was delighted, and in truth surprised, to find Maclay alive. Far from needing support and protection he had made friends among the local inhabitants and was fending well. At first Maclay was undecided whether he should leave with the ship or reprovision and stay. There had been setbacks as his young Polynesian servant had died and the other, a Swedish seaman Olsson, was a burden, frequently unwell and dispirited. This, coupled with his own health which was declining from malaria led him to make for Batavia where he recuperated and published his anthropological findings.

For a number of years, still with irregular support from the Imperial Navy, he continued his exploration and studies throughout the region comparing the characteristics of various native peoples. He grew anxious about the future of these primitive people; their land and culture threatened by exploitation and, sought assistance from colonial powers in stopping the trafficking of firearms and intoxicants to vulnerable people. He made three visits to the Maclay Coast spending a total of three years living in this region and gaining a unique insight into the ways of the local population. Believing that he could now achieve more from a settled environment in July 1878 he arrived in Sydney with a large collection of artefacts, specimens and drawings

The exotic, handsome, aristocratic and well educated Russian explorer enchanted colonial society. He became an intimate of the leading Australian naturalist and zoologist and political figure Sir William Macleay. He assisted in establishing the Macleay specimen collection which is now housed in the University of Sydney. Shortly after arriving in Sydney he approached the Linnean Society offering to organise a zoological centre. In September 1878 his offer was approved and the centre, known as the Marine Biological Station, was constructed by the prominent Sydney architect, John Kirkpatrick. This facility, located in Watsons Bay, was the first marine biological research institute in Australia. The Marine Biological Station was commandeered by the Ministry of Defence in 1899 as a barracks.

State Library of NSW

Maclay could have been content with his new comfortable surroundings and absorbing scientific studies but he could never forget the revolutionary politics of his youth. On 8 April 1881 the Melbourne Arguscarried an open letter from Maclay to Commodore John Wilson, the Commander-in-Chief of the Australia Station, which in part reads:

That the exportation of slaves (for it is only right to give the transaction its proper name) to New Caledonia, Fiji, Samoa, Queensland, and other countries by kidnapping and carrying away the natives, under cover of false statements and lying promises, still goes on to a very large extent, I am prepared to aver and support by facts.

He continues with further examples and submits to Wilson further documented evidence of a flourishing slave trade between Australia and Oceania.

The relationship between Scientist and Commodore prospered as in August 1881 Maclay was invited to accompany Wilson aboard his flagship HMS Wolverine on a punitive expedition to the New Guinea south coast where natives had killed missionaries. Maclay was familiar with the area and thought he could help isolate the culprits and avoid the usual punishment of widespread destruction of villages and crops and the taking of hostages, until some undeserving wretches were delivered for summary punishment. Whether his intervention succeeded is a matter of debate as the outcome was a large landing party surrounding the village of the suspect chieftain who, with a handful of his followers was killed, and only the chief’s house was razed. Honour appears to have been satisfied and the lessons well learned by adjacent tribes who in future respected the role of missionaries.

Demonstrating that Maclay’s approach was even handed and he was not just criticising Europeans for their abuse of native peoples there are two letters (in his Travels to NewGuinea) to the Governor-General of the Netherlands Indies. These speak of abuse of Papuans by Malay slave traders operating along the southern coast of New Guinea conducting plunder, assault and unwarranted destruction. In particular he mentions the spice island Sultanate of Tidore as being the main instigator with the Sultanate being under Dutch protection.

When the Russian Pacific Fleet visited Melbourne in February 1882 Maclay joined HIMS Vesnik and returned to the Baltic port of Kronshtadt in September. Maclay undertook lecture tours in his homeland and was awarded the Imperial Geographical Society’s gold medal and presented with a certificate of honour by the Tsar. The next year he returned to Batavia and from here in a familiar ship Skobelev (Vitiazhad been refitted and renamed)took the now famous explorer back again to Astrolabe Bay. Maclay persuaded his hosts to purchase livestock (a bull, a cow a billy and she-goats) plus coffee beans which were presented to the people of Astrolabe Bay. Unfortunately conditions had deteriorated unfavourably during his absence due to the influence of European adventurers.

He was particularly alarmed to discover that in April 1883 the Colonial Queensland Government had annexed Papua for the British Empire. Understanding full well the fate awaiting New Guineans under such an unenlightened administration he appealed to Sir Arthur Gordon, the British High Commissioner in the Western Pacific. Sir Arthur, as the younger son of the highly respected British statesman the Duke of Aberdeen, was politically well connected. This helped persuade the British Government’s refusal to ratify the arbitrary Colonial annexation and, to overcome this unfortunate incident, in November 1884 a protectorate was declared over British New Guinea. But his beloved Maclay Coast could not be saved as negotiations between the European colonial powers saw the north eastern part of New Guinea given to others, and again in November 1884, the German flag was raised over Kaiser-Wilhelmsland.

Much against her family’s wishes, in February 1884 Maclay married Margaret-Emma Clark, the widowed daughter of the long-standing Premier of New South Wales, Sir John Robertson. Early in 1886 he returned to Russia with his new family and twenty-two boxes of specimens. He arranged for some further publications and conducted lecturers. He intended to return to Sydney but his health deteriorated and he died in 2 April 1888. Not yet 42 years of age, he had achieved much and with a revolutionary zeal remained true to the idealistic aims of social democracy for all mankind. His wife and two sons returned to Sydney where their descendents remain.

A Russian Colony in the South Pacific

Nickolai advocated establishment of a Russian protectorate on the Maclay Coast and suggested ideals of Russian expansionism to those in power in St. Petersburg. He noted there was a mood of expansionism in Australia, particularly towards New Guinea and the islands in Oceania. He also wrote to Tsar Alexander III in which he suggested that due to the lack of a Russian sphere of influence in the South Pacific and English domination in the region, there was a threat to Russian supremacy in the North Pacific.

Maclay expressed his willingness to provide assistance in pursuing Russian interests in the region. Nicholas de Giers, the Russian Foreign Minister, suggested in reports to the Tsar that relations with Miklouho-Maclay should be maintained due to his familiarity of political and military issues in the region. This opinion was mirrored by the Naval Ministry. In total, three reports were sent to Russia by Miklouho-Maclay, containing information on the growth of anti-Russian sentiment and the build-up of the military in Australia, which correlated with the worsening of Anglo-Russian relations.

Noting the establishment of coal bunkers and the fortifying of ports in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide, Maclay advocated taking over Port Darwin, Thursday Island, Newcastle and Albany. The Foreign Ministry considered a Russian colony in the Pacific as unlikely and military notes of the reports were only partially utilised by the Naval Ministry. The authorities in Russia appraised his reports, and in December 1886 de Giers officially advised Miklouho-Maclay that his request for the establishment of a Russian colony had been declined.

Retrospect

While now largely forgotten Maclay gained international repute and is fondly remembered in his homeland. His Russian Biographer Daniil Tumarkin says: The most striking thing about Miklouho-Maclay is an amazing combination of the qualities of a courageous traveller, an erudite scholar, a progressive thinker and humanist, an active public figure, and a fighter for the rights of oppressed peoples. Taken separately, there is nothing exceptional about these qualities, but the combination of them in a single person was an unusual phenomenon.Gabriel Monod, the well-known French historian, wrote in La Nouvelle Revuein 1882: Russia should be proud of the outstanding position she occupies in the history of travel owing to M. Maclay. This man is the most sincere and consistent idealist whom I have ever met. An idealist and man of action – are these not the traits of a genuine hero? Miklouho-Maclay is a hero in the noblest and all-embracing sense of the word.The world renowned author and philosopher Leo Tolstoy in a letter written to Maclay in 1886 says: You were the first to demonstrate beyond question by your experience that man is man everywhere, that is, a kind sociable being with whom communication can and should be established through kindness and truth, not guns and spirits.

In his time Maclay was one of the brightest stars of scientific research. His scholarly and humanitarian achievements are mainly linked to living and working in the jungles of New Guinea with then almost unknown tribesmen. From here he came to New South Wales where he established a new home and wrote of his experiences. Above all he placed humanity first and, if he did delve into the world of espionage and intrigue, it was surely done with the best of motives. While some monuments to him are to be found in Australia, New Guinea and Russia a more fitting tribute is Moscow’s Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology named in his honour and the annual Macleay Miklouho-Maclay fellowship, awarded by the University of Sydney.

Bibliography

Barratt, Glynn, The Russians at Port Jackson 1814-1822, Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1981.

Govor, Elena & Ballard, Chris, A Mirror in the South Seas: Russian perspectives on New Caledonia during the nineteenth century, Canberra: Australian National University, 2010.

Mennis, M.R., Mariners of Madang and Austronesian Canoes of Astrolabe Bay, Research Report Series Volume 9, University of Queensland, 2011.

Miklouho-Maclay, N., Travels to New Guinea – Diaries Letters Documents, Moscow: Progress Publishers – English translation, 1982.

Australia–Russia Relations

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australia%E2%80%93Russia_relations>. Accessed 30 April 2015.

Early Visits of Russian Warships to Australia

<http://ahoy.tk-jk.net/macslog/EarlyVisitsofRussianWarsh.html>. Accessed 30 April 2015.

Australian Dictionary of Biography

<http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mikuho-maklai-nicholai-nicholaievich-4198>. Accessed 30 April 2015.