- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Ship histories and stories, History - WW1, WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

William Kinnersley was born in Wales on 20 September 1896 and died aged 95 on 17 May 1992 at Collaroy, NSW. After Royal Naval service during the First World War he emigrated to Australia in 1925 where he worked in radio electrical engineering. He lived at Mosman with his wife Kathleen and their son Donald. ‘Uncle Bill’ was dedicated to the Scout movement and in later life became something of a celebrity speaker, especially at Masonic Lodge meetings. With his melodious Welsh lilt he had a gift for eloquence coupled with a vivid imagination and excellent recall of historical detail. To enliven his stories Bill often transposed himself as principal actor in the midst of the scenes he so graphically described.

The following address by William Kinnersley has been transcribed from the original of a cassette tape recording made to a Sydney Masonic Lodge in the early 1970s. William tells of his service as a Midshipman RNVR with the first landing of ANZAC forces at the Dardanelles on 25 April 1915. We now know that Bill was a veteran of the Battle of Jutland but this was of little interest to an Australian audience who wanted Gallipoli and the Somme. If Anzac was needed then who better to provide this than Uncle Bill?

Australia Will Be There

The address starts with a recording of a famous marching song capturing the spirit of the time, Australia Will Be There by Walter William (Skipper) Francis. Songs like these were the last strains men heard from their homeland as their ships cast off from docksides on their way to the far distant war in support of the mother country.

Rally round the banner of your country

Take the field with brothers o’er the foam,

On land or sea, wherever you be

Keep your eye on Liberty;

But England home and beauty

Have no cause to fear

Should Auld acquaintance be forgot

No! No! No – No – No!

Australia will be there, Australia will be there.

Worshipful Master,

May I thank the Brethren of this Lodge for the tolerance I hope they will extend to me tonight, an old man, with a difficult task. I cannot give you oratory but I can offer you sincerity. As I am not a lecturer I would prefer a yarn with the Brethren.

Once again it is April which in Australia emanates an aura which we call ANZAC with these letters standing for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps. Some people of my vintage shake their heads saying ‘Anzac Days are not what they used to be’, and perhaps they are fading out, and with the last Digger they will be gone. Younger men who have fought their own war, and have done well in them, brashly say Anzac Day is gone. And still younger people say it should be forgotten, as it is part of history. And most of us just grab the holiday instead of making it what it should be, a holy day. But I advert that Anzac must not be forgotten, as it is part of our history, it is a noble cause that preserves from oblivion those things that should be stored and eternally remembered. And is not Anzac one of those? No, Anzac day will not be forgotten.

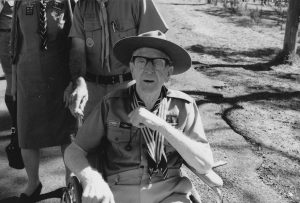

Kinnersley Family Archive

Those cemeteries on the Heights of Gallipoli are unlike those of any other war. It was early decided that the dead should be buried close to where they fell. Consequently there are a score or more cemeteries lying close to the Heights, some with a hundred bodies and others contain thousands, and they are all nearly on the Heights where the fighting reached its zenith. Each cemetery is surrounded by banks of pine trees and the graves, which are marked by plaques, are set about by cypress, juniper, rosemary, arbutus and judas trees. They are cared for by the descendants of the people who killed them. The effect of these cemeteries is not one of tragedy and death but a great sense of peace and tranquillity.

‘…pimply faced indolent oafs’

In 1913 German missionaries who had travelled freely throughout the British Commonwealth made observations of Australian characteristics with reports sent home to their church leaders and, one reached the war lords in Berlin. This said that any armies coming from the Antipodes would consist of but gamblers, horse lovers, and pimply faced indolent oafs. And with them the story began. It was these pimply faced oafs that leapt from their boats in 1915, waded through the water and on to the beach and fixed bayonets. Let me be clear, these Anzacs were not on their own. The French were there as I saw them, with some French officers in black and gold uniforms of the parade ground, with soldiers in scarlet tunics and bright dark blue breeches. The Foreign Legion wore light tropical uniform of the North African deserts. Sikhs and Ghurkhas were there too, also men representing nearly all the county regiments of the British Army. And with all these there were several thousand young men, barely 17, from the British Naval Division. They had been given just seven weeks training in squad drill on the nice green lawns of Crystal Palace or the parks of Penge and Dulwich Hill and, another three or four weeks at Blandford in Dorsetshire on the range and digging trenches. Then four days leave and, then gathering their equipment, were shipped to the Dardanelles and death. I speak very feelingly as from my own school there were forty of them and not one returned.

The Anzacs had no battle-scarred officers to nurse and coax them and no great military traditions to which they might aspire. Few of them had any military ancestry to follow. They had to make their own traditions; they had to prove themselves to themselves and this they surely did on those beaches. I said beaches – they were barely narrow strips of mud leading to imponderable hills, each one registered by a letter of the alphabet. Jack Churchill (Winston’s brother) who was a war correspondent for the ‘Times’ wrote a poem about ‘Y Beach’:

Y Beach, the Scottish Borderer cried,

While panting up the steep hillside

To call this a beach is stiff

It’s nothing but a bloody cliff,

Why Beach?

Three naval warships of the British Mediterranean Fleet (London, Prince of Wales and Queen) with their escorts and a large number of transports steamed fervently towards Gaba Tepe. We reached our destination in the dark when anchors were lowered slowly and quietly. On board the battleships there were large numbers of Australian soldiers. It was intended that they would be the first ashore. Each ship had a number of pinnaces and behind each were three barges which would form tows to be taken ashore.

The last hot meal on board

After anchoring, the lower booms were swung out on both sides of the ships and the boats secured, fires were lit and steam raised. We supernumeraries inspected our boats and the tow of three barges which held about 40 men each. And then we inspected them again and still again. About 12 o’clock (midnight) the troops were called and then sent below for their last hot meal on board. The order came for the men to be loaded into the boats and given their instructions, there was to be no smoking and they were told to keep quiet. The boats were tightly packed and were most uncomfortable. Here we hung about for a couple of hours which seemed an eternity. Each one of us, I believe, fought one of man’s greatest enemies, the unknown. From one of the boats I heard a hoarse whisper saying ‘look at that kid’ (he meant me) standing up there as stiff and straight as a rifle barrel’. And another said ‘I bet he’s scared stiff just like me’. Of course I was, but I hissed back ‘keep quiet in the boats’. Around 4 am the signal came and we steamed at full speed over several thousand yards for the shore. I imagined what might happen if one of the boats coming from the other side of the ship came across our bows and we collided so I veered out to starboard. At last there was the beach which looked like several Paddy’s Markets with everything imaginable from tents, corrugated iron, food and water, mules and donkeys and at one end a blacksmith’s shop and at the other end a signal station which looked like an Australian humpy after a cyclone. We came ashore, discharged our troops and then returned for other work.

Over the next few days we hung about doing all sorts of duties carrying dispatches from ship to ship, transporting the wounded back to hospital ships, dodging dead mules that floated on the water upside down, very bloated, with their legs straight up looking like tables with their legs in the air.

German (sic) artillery was picking off our boats and I had worked out my own form of zigzag plan. One morning our boat was struck by shellfire right on the waterline and we quickly began to sink. My petty officer said, ‘Well Sir we had better abandon her’ and he and the engine room hand and the bowman who could all swim jumped in hoping to be picked up by passing boats – I have never seen or heard of them since. As I could not swim1 I was wearing a life jacket and with a little hope and not much faith prayed for deliverance. I eventually passed out, coming to when washed onto a rocky outcrop. Here I was discovered by a passing boat which had Captain Edward Unwin, VC on board. As Captain Unwin had lost his ship, the transport River Clyde, he had been found another position on the Commodore’s staff. Knowing that a Midshipman without a boat was not highly prized as yet another mouth to feed he took me aboard his own ship and I was tasked with all those little jobs that no one else wanted.

Paper boats

As I told Captain Unwin the story of being washed ashore he had me return to this spot and spend three days making paper boats and chasing them to observe the state of the tide. While this could be regarded as playing games I was told later that the information proved very useful in taking boats back to our ships, making the best use of the tide, when we eventually evacuated the beaches.

Later on I was given a new pinnace and instructed to take an important party ashore which included: Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Hungerford Pollen – Military Secretary to Sir Ian Hamilton, C-in-C of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force; Major Jack Churchill (Winston Churchill’s brother); Lieutenant R.M. Compton Mackenzie of ‘Whisky Galore’ fame and A.P. Herbert (SBLT Alan Patrick Herbert, RNVR – poet and novelist and later a MP).

‘…no billies and no tea!’

A truce had been called to discuss burial of the dead. We had to make our way up to a cave. Here there were Turkish, German and British officers and some of ours. I did not go inside but stayed out with the cooks. From the conversation I heard from the cooks it led me to the conclusion that 99% of Australians were born out of wedlock. One of them shouted out ‘which of you bastards have got the billy cans; no billies and no tea’. An officer came out from the cave, said nothing and gave him some billies. What tolerance I thought.

I overheard Pollen trying to start a conversation talking to three Australians, not one of whom was less than six foot tall. Pollen, who had a soft, somewhat ecclesiastical voice, was saying ‘Have you chaps heard that they’ve given General Bridges (Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges who died of wounds on 18 May 1915) a posthumous KCB’. ‘Have they?’ one of the giants replied. ‘Well, that won’t do him much good where he is now, will it mate?’

A.P. Herbert came along and started us up a hill going to the Heights. We were on our tummies making three steps forward and sliding two backwards. Going up we came across a group of Australians coming down. Pollen looked at them and tried to speak but they did not salute and ignored him. Later another group of Australians came down and saluted smartly, difficult as it was for Pollen as he was still crawling along on his tummy, he returned the salute. I heard one of them say ‘that’s what you call British politeness.’ Pollen looked at them and shook his head.

We got to the trenches eventually; pretty rough going and we were not much more than a cricket pitch from the Turks. I looked through a trench periscope and could see the Turkish soldiers up above sitting on the edge of their trenches having a smoke. I tried bringing this information to the attention of an officer, a Major. He said ‘oh they’re alright, they have been there all morning, we know where they are and it’s all quiet, if they want a bit of a stoush we will be ready’. I did not know what a stoush was at this time. The Major told two soldiers with fixed bayonets to keep an eye on me. It was then that I learned what might happen to young men captured in some of the raids – and it was not nice. I was terrified and anxious to get back. Compton Mackenzie said I broke all records going down from the trenches to the beach.

Joining the Grand Fleet

I was told that with a number of other supernumerary midshipmen who were no longer required we would be going back to Britain to join the Grand Fleet. And I was given the task of going around the fleet finding the names of those being returned. Eventually we were all taken to the Greek island of Mudros to await transportation back home. Here we could obtain new supplies and I was presented with a new uniform with a brand new gold stripe ready to be sewn on. I was told of a beautiful Australian nurse who ran a field hospital from a large tent. I managed to find her and not having any female company for many months she seemed like an angel of peace. She provided extra blankets to escape the cold and offered to have my stripe sewn on. A few days later we joined HMHS Britannic2 and so made our way to England. Also boarding Britannic was an Australian, Mr Dickers, who had been aboard one of the transports and was now to join the RNR.

When we arrived home after some leave Dickers went to Portsmouth for gunnery training and I went to Plymouth for torpedo instruction. We were both to meet up again a short time later on a ship (HMS Constance) being fitted out at Cammell Lairds at Birkenhead. It took me months to get Dickers to understand that the Navy had rules that had to be obeyed. After falling foul of the Captain he was eventually transferred to HMAS Anzac.

I was lent to a Q ship the Argo3, an old sailing vessel which could do no more than 8 knots. She was disguised as a tramp and on deck there was a large coil of rope but inside there was a gun with sighting holes. The crew was dressed up in civilian clothes and I had to pretend to be the captain’s wife. These ships were so successful against U Boats that they soon reverted to their normal mode of torpedoing targets rather than attempting boarding and sinking them with explosives.

I had another experience with Australians as the Army and the Navy had decided it was quiet enough for an exchange of officers and so I volunteered. On reaching Boulogne I was more or less captured by an Australian in a slouch hat and taken in a car…

(Here the cassette recording ends).

William Kinnersley – Service Record

A copy of William Kinnersley’s service record obtained from the National Archives shows his DOB 20 September 1896 and entering the RNVR Wales Division Service No Z 1269 on 1 June 1915. He was not called up until 14 September when just short of his 19th birthday he entered the service as an Able Seaman. He was 5 feet 7 inches tall with brown hair and grey eyes with a slight build. Prior to joining the Navy he had followed his father down the pit as a coal miner. His list of service postings comprise:

| Ship | Rating | From | To |

| Victory 1 | AB | 14 September 1915 | 15 September 1915 |

| Caroline | AB | 16 September 1915 | 25 February 1916 |

| Constance | AB | 26 February 1916 | 26 February 1917 |

| Vivid 111 | AB | 27 February 1917 | 18 October 1917 |

| Defiance | AB | 19 October 1917 | 9 January 1918 |

| Vivid 11 (IB 033) | AB | 10 January 1918 | 7 June 1918 |

| Vivid 111 | AB | 8 June 1918 | 13 June 1918 |

| Diligence (Scout) | AB | 14 June 1918 | 23 July 1918 |

| Constance | AB | 24 July 1918 | 13 March 1919 –Discharge ashore |

HM Ships Caroline and Constance were both new ‘C’ class light cruisers and served in the North Sea as part of the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron. The latter ship served at the Battle of Jutland (31 May to 1 June 1916) when Kinnersley was serving in her. Caroline is the last surviving vessel to have taken part in the Battle of Jutland where she came under fire from a Deutschland-class battleship, but escaped unscathed. After many years as the RNR Northern Ireland headquarter ship she finally decommissioned in 2011 when she was the second oldest ship in Royal Navy service after HMS Victory. She is now being preserved as part of the Titanic Quarter of Belfast.

HMS Vivid (using various numbers) was part of the Royal Naval barracks at Devonport. Personnel posted to Vivid were sometimes detached to small ships, this is possibly the significance of IB 033 which is believed to have been a torpedo boat tender.

HMS Defiance was the torpedo school at Devonport so Kinnersley would have qualified as a torpedoman.

HMS Diligence was a destroyer depot ship and the reference to HMS Scout refers to a new destroyer which was commissioned in June 1918 so it appears Kinnersley was standing by this ship but he did not in fact join her.

John Dicker, Able Seaman Royal Naval Division and Lieutenant Royal Naval Reserve

In his address to the Masonic Lodge reference is made on three occasions to a Mr Dicker(s) who later joins the RNR. The Royal Navy Lists confirm that Lieutenant John H. Dicker, RNR was posted to HMS Constance in February 1916 and was still serving in her in July 1918. Quite remarkably a photograph has been discovered dated 1918 of Lieutenant Dicker, RNR serving aboard HMS Constance.

Following research through the National Archives the service records of John Henry Dicker were obtained. These show he was born at Burnham, Essex on 8 July 1891 and his father was John L. Dicker, head of the Coastguard4 station based at Sheerness. The Royal Naval Division was formed in August 1914 so John Dicker was an early volunteer entering as an Able Seaman on 17 September 1914. His service no. was London Z/410 and he was posted to the Benbow Battalion. Up until this time he had been in the Merchant Navy and possessed a First Mate’s certificate but was serving as Second Mate in a cargo ship. At the time of engagement he was 5 feet 10.5 inches tall, with brown hair and blue eyes, having a chest measurement of 38 inches – for his time he was quite a tall and well built man.

While his service record does not state where he went after initial training at Blandford, most Benbows departed from Plymouth in the troopship Ivernia in early May 1915, arriving at Lemnos on 22 May. They landed at ‘V’ beach using the wrecked River Clyde (also mentioned by Uncle Bill) as a temporary jetty on 25 May. These troops were soon to see action and on 12 June he was transferred to the Anson Battalion. On 30 June he was admitted to the Dardanelles Hospital suffering from nervous shock and later enteritis.

While he temporarily rejoined his unit he was subsequently invalided by the hospital ship HMHS Hunslet5 to England. He was discharged from Haslar Naval Hospital at Portsmouth for duty on 26 November 1915. During this period he appears to have passed a selection board for Officer Cadet but at his own request he was discharged from the RND on 18 January 1916 and was commissioned into the RNR as a Temporary Sub-Lieutenant on 28 January 1916. His new service no. was 1160.

Paymaster LCDR E Hopkins, RN archive

His initial posting was to the Royal Naval Gunnery School at HMS Excellent for HMS Constance. Constance was a new ‘C’-class light cruiser building in Cammell Laird at Birkenhead. She commissioned in January 1916 and he joined her 17 February 1916 and stayed in this ship throughout the remainder of his service career. As Constance was at Jutland he would have again seen active service and shortly afterwards on 27 July 1916 he was promoted to Acting Lieutenant and as Temporary Lieutenant on 24 January 1918. He was demobilised on 16 March 1919 and returned to the Merchant Service where he passed for his Master’s certificate on 23 May 1919 and is last recorded as serving as First Mate on an oil tanker. Uncle Bill’s allusion to Dicker being an Australian and later posting to HMAS Anzac appears to have been a red herring as there is no record of an officer by the name of Dicker serving in Anzac during this period.

Farewell to Uncle Bill

Our likeable Uncle Bill who so eloquently described the landings at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 had at that time yet to join the Royal Navy and did not serve in this theatre. His naval service was as an Able Seaman RNVR restricted to home waters and the North Sea; he did however see active service at the Battle of Jutland. There is much in William Kinnersley’s story closely resembling the service career of John Dicker and coincidently both men served together in Constance for a year, from February 1916 to February 1917 and again for 8 months from July 1918 until they were both discharged ashore in March 1919.

Rudyard Kipling once said ‘If history were taught in the form of short stories, it would never be forgotten’. Did not then Uncle Bill with his stories pay tribute to the historical record?

Endnotes:

1 The battleship HMS Russell flying the flag of RADM Sydney Fremantle (later Admiral Sir Sydney) took part in the evacuation of troops from the Dardanelles. When waiting off Malta at night on 26 April 1916 she struck mines recently laid by U-73 and quickly sank. Although many were rescued by boats from Malta there was a loss of 124 lives. Admiral Fremantle finished his career as C-in-C Portsmouth where he introduced compulsory swimming tests for the Royal Navy.

2 HMHS Britannic, a sister to Olympic and Titanic, was one of the largest ships afloat. She made five successful voyages to the Middle East as a hospital ship but on her fateful sixth voyage on 21 November 1916 when off the coast of Greece she was either mined or torpedoed and sank. At this time she did not have any patients on board and only 30 lives were lost.

3 Argo was a small cargo vessel of 661 tons which was built in 1906 and requisitioned by the Admiralty in June 1917, initially as a store ship and later a ‘Q’ ship.

4 From the 1830s to the 1920s the British Coastguard formed part of the reserve forces of the Royal Navy and could be recalled to active service during times of emergency.

5 HMHS Hunslet had started life as SS Tannenfels, an auxiliary attached to the German Naval Pacific Squadron. She was captured in the Philippines and taken to Britain where she was converted for use as a hospital ship.