- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- None noted

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Commander Neil Westphalen, RAN

Let us assume it’s 0915 on a Monday and you are the CPOCSM for a major fleet unit that is due to sail at 1000. While finalising your pre-sailing report for the WEEO, you discover that LSET Bloggs is about to be landed for medical reasons. This matters, as she is the last person available who is qualified to calibrate an obscure combat subsystem as an important part of the week’s workup. As the WEEO heads to the bridge to tell your CO that it won’t be happening, you see Bloggs being helped down the brow with her kit, in obvious pain. What just happened?

Introduction

It may come as a surprise that, apart from a doctrinal reference regarding deployed operations, the ADF has never had a truly comprehensive military health strategy. Like other Western military services, since the mid-1970s ADF health policy has instead been premised on various assumptions, in particular that health services only exist to treat patients, and that uniformed health staff are required only because civilians cannot deploy. This has led to its health services long being considered an obvious exemplar of something that could easily be unified or contracted out.

Moreover, the ADF’s Middle East operations since 2001 have led to the terms ‘deployed’ and ‘operational’ health services being used more or less interchangeably. The ensuing failure to differentiate between the two means that at present, Navy (and RAAF) operations from Australian soil are supported by ‘garrison’ health services that are deemed ‘non-operational’ because they themselves do not deploy.

ADF operational capability is further hampered by excessive rates of preventable work-related injuries and illness (up to 90 percent of which has not been reported) even without deploying. Besides the cost of their treatment, rehabilitation and compensation, costs associated with the time lost from duty can be added, and for those unable to return to work, recruiting and training hard-to-replace skilled personnel. Meanwhile, the ensuing high rates of long-term mental health conditions have led to the 2019 Productivity Commission veterans’ health inquiry, and the current Defence and veteran suicide Royal Commission.

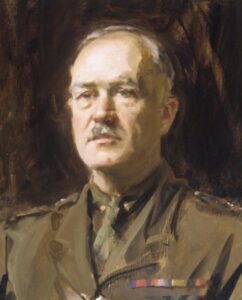

Yet in 1940, Colonel Arthur Graham Butler’s classic World War I official medical history identified what he termed the three elemental ‘purposes’ of military health services. Suitably updated, his purposes (missions) are central to a truly comprehensive and effective ADF military (including naval and RAAF) health strategy, based on an occupational health-based model.

The aim of this paper is to summarise Butler’s purposes, and their relevance to LSET Bloggs.

Butler’s ‘purposes’

Butler described his ‘purposes’ as follows: ‘As we follow the course of the casualties, sick and wounded, from the front through the various levels of evacuation to their distribution and final disposal…we find three prime purposes intermingling in the manifold activities of the medical service…To the military command, it owed service to promote and conserve manpower for the purpose of war. To the nation at large, it was responsible for promoting…the efforts of the civil institution whose duty it should be to prepare for useful return to civil life the soldiers unfitted for further military service. By Humanity…it was charged with minimising…the individual sufferings of the combatants of both sides. These three strands of purpose, inextricably interwoven as they were, in a self-contained and consistent scheme of medical service nevertheless furnished each as an end in itself—all three entering at every stage into the medical problem, and now one, now another, providing its dominating motive.’

Butler’s distinguished Gallipoli and Western Front service ensures his credibility as a military clinician and administrator, attributes he shared with many of his contemporaries. Unlike his contemporaries, however, he spent the rest of his working life writing a seminal history that comprehensively analysed the enduring elemental lessons learned by the Australian Army medical services during World War I. Regrettably, however, these lessons have since been lost, not least by subsequent Australian official military medical historians.

Previous reference has been made to the assumption that military health services only need to treat patients. To this end, Butler agrees that military health services have an obligation to minimise the suffering endured by service personnel. Furthermore, the extent to which this mission is no different to that of civilian health services means that it is well-understood by civilian health providers.

However, this assumption ignores the fact that civilian health services have no remit regarding the other two missions. Furthermore, military health services are also differentiated from their civilian counterparts, in that the population they provide care for is (by definition) exclusively working age, whose clinical conditions (in particular their musculoskeletal injuries and mental health disorders) are therefore either caused by their work, or affect their ability to perform their work. These conditions reflect the plethora of physical, chemical, biological, ergonomic and psychosocial workplace hazards to which ADF members are exposed, even without deploying. To these can be added combat-related workplace hazards that are deliberately intended to cause harm.

These considerations account for why the modern ‘treatment service’ mission is far broader in scope than Butler’s Army-only WWI setting. Furthermore, the work-relatedness of the illnesses and injuries requiring treatment explains why conducting this mission necessitates an occupational health-based strategic model.

Non-combat-related injuries and disease

Butler also noted that military health services owe an allegiance to commanders to promote and conserve personnel for the purpose of war. To this end, he wrote extensively elsewhere regarding the medical, dental and other measures necessary to fulfil all three ‘purposes’, through preventing avoidable non-combat-related injuries and disease. In addition, he described how, if these measures fail, his ‘purposes’ entail two tasks. The first is to provide timely treatment and rehabilitation: besides fulfilling his ‘treatment purpose’, this reduces patient downtime from their normal duties (his ‘command purpose’), and the risk of long-term impairment, thereby reducing future compensation costs (his ‘national purpose’). The second task requires patients undergoing a medical review on regaining their maximum post-treatment functionality, which either returns them to their normal duties (his ‘command purpose’), or recommends their medical discharge, with the relevant civilian institution(s) providing for their subsequent medical care and compensation (his ‘national purpose’).

It should be noted that Butler’s experiences reflected an especially horrific form of industrialised attrition warfare, for which personnel conservation as an end unto itself proved essential to victory. The same could also be said of the World War I campaigns in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and East Africa, and the World War II Burma and South-West Pacific campaigns, where the medical components to ensuring operational success pertained less to managing combat casualties than to controlling overwhelming rates of preventable infectious disease.

Even so, despite undertaking clinical duties at Duntroon from 1927 to 1930, Butler seems not to have recognised the extent to which his ‘command purpose’ extends beyond wartime Army operations, most likely because the Army at that time – including its medical services – almost exclusively comprised a part-time militia that was not liable for overseas service. This contrasts with Navy, whose peacetime operations have always required health support, especially where shore-based services are not available within an operationally or clinically appropriate timeframe.

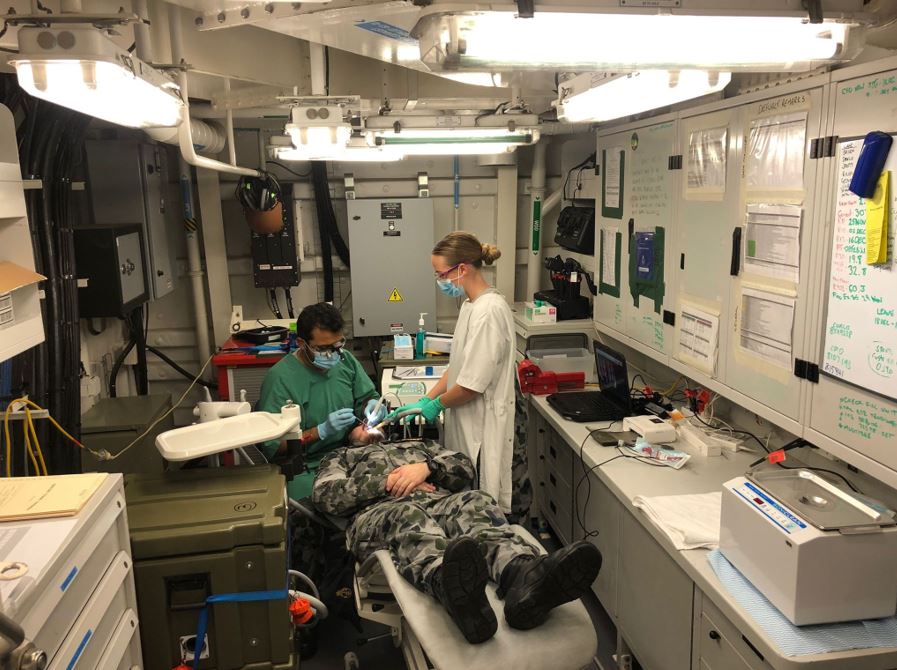

This explains why the RAN medical services ‘command purpose’ is not limited to just conserving personnel, but entails all the additional clinical and non-clinical medical measures necessary to get ships to sea and keep them there. This firstly requires health staff ashore as well as afloat, who not only prevent medically unsuitable personnel from going to sea, but can also ascertain who can still go sea despite their medical condition(s). This requires a risk management approach based on two components: understanding how each patient’s medical condition(s) limit or prevent them doing their job at sea, and vice versa, i.e., considering the potential for their job at sea to worsen their medical condition(s).

Keeping ships on-task also requires seagoing health staff who can avoid landing patients unnecessarily, or if this is not possible, use the resources available for however long it takes to reach a shore location that can provide better care than on board. These demands extend beyond Navy’s General Service personnel to its aircrew, divers and submariners, whose operational capabilities that they provide require dedicated health support.

To these ends, it seems reasonable to assert at this point that health staff with actual seagoing experience are better able to get ships to sea and keep them there than those without, and that those with more seagoing experience are better at doing so than those with less. Yet, this assertion conflicts with the assumption that Navy only needs uniformed health staff because civilians cannot go to sea. Even so, it explains why conducting this mission likewise necessitates an occupational health-based strategic model.

Butler notes that military health services owe an allegiance to the nation at large to facilitate the civil institutions responsible for returning military personnel deemed unfit for further service to the civilian community. For more than a century, the primary institution he referred to has been theDepartment of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) and its antecedent organisations. However, while the Productivity Commission inquiry confirmed the need for substantial reform (particularly regarding rehabilitation and compensation), many of its recommendations are still based on the aforementioned assumptions.

It should be noted that Butler began writing his history in 1923, when ‘the Repat’ provided services for hundreds of thousands of mostly ex-AIF members with war-related illnesses and injuries, and when many ‘Repat’ service providers themselves had had wartime experience. Among other considerations, this meant that they could, for example, ‘fill in the gaps’ when reviewing each claimant’s often scant wartime clinical and other documentation, perhaps decades later. Post-World War II ‘Repat’ assessors likewise possessed this capability into the 1980s as, again, many had wartime service comparable to that of many of the claimants they were assessing.

Vietnam War veterans

However, the tribulations endured by Vietnam War veterans and their successors indicate the extent to which modern civilian health practitioners have no such experience. The claims process is further hampered by the current exclusion of military occupational physicians from the assessment process, despite their specific training in assessing clients, providing impartial advice regarding their eligibility and treatment, and facilitating their return to work.

This explains why all ADF personnel—not just the medically separated members referred to by Butler—should be managed as potential DVA clients from when they first join. This has two components: preventing avoidable work-related illness and injuries (i.e. DVA claims) in the first place, and reporting all work-related illness and injuries when they first present to ADF health staff.

Although assessing injury work-relatedness can be straightforward, this may not always be the case for conditions such as mental health disorders, whose clinical effects resulting from work-related exposures and vice versa may not be readily apparent. It therefore seems reasonable to assert that assessing work-relatedness can be somewhat problematic without an understanding of what the member’s job actually entails: this requires medical practitioners either with comparable workplace (i.e. service) experience, or training for those without such experience that is not provided at present.

Meanwhile, the current organisational split between the clinical services provided by Joint Health Command, and the illness and injury reporting process to the Defence Work Health and Safety Branch, is actively inimical to achieving this mission. This situation is not improved by largely bureaucratic rehabilitation processes that lack specialist rehabilitation and occupational physician clinical input, and have no outcome measures that actually include the return of ADF members to their normal duties. These deficiencies further support the contention that the military health services ‘civilian transition’ mission requires an occupational health-based strategic model.

Butler notes that his ‘purposes’ are not discretely separate but intrinsically linked depending on circumstances. To demonstrate this point, let us return to LSET Bloggs. It turns out she first presented to the sick bay at 0735 with shoulder pain, but was not seen by Dr Smith until 0900, because other patients were deemed more clinically urgent. Besides the normal clinical process of taking Bloggs’s medical history, examining her shoulder, performing investigations, formulating a diagnosis and prescribing treatment (i.e. the ‘treatment mission’), Smith needed the skills and expertise to also consider the following, despite typically lacking a military service background.

The ‘operational capability mission’.

Smith needed to consider whether Bloggs’s diagnosis and/or treatment limited or prevented her performing her seagoing duties, or vice versa—that is, whether her seagoing duties would adversely affect her diagnosis or treatment. If so, Smith then needed to consider how either or both affected her CO’s mission. In this case, Bloggs being the sole ET qualified to calibrate the combat subsystem may have led to substantial changes in her clinical prioritisation and personnel management if she was unfit for sea, compared to LSET Jones, who has the same skills but is posted ashore, who Smith saw the week prior with the same diagnosis.

The ‘civilian transition mission’.

This should have entailed Smith carefully documenting how and why Bloggs’s injury occurred. Once again, this aspect of her management would be different if it occurred while performing her secondary ship’s diver duties the week prior, compared to LSET Jones who injured his shoulder at home. Besides documenting work-related illnesses or injuries for future treatment liability and compensation purposes, Smith’s patient management IT system should have also initiated the DVA reporting process and help prevent future injuries (in Bloggs’s case, having lifting equipment to move heavy gear into the dive boat), rather than expecting Bloggs or her divisional chain to record these details separately as at present.

Besides demonstrating how these missions are intimately linked, Bloggs’s case explains why military health services are more complex (and hence bureaucratic) than civilian health organisations that only have one mission. It also demonstrates the fallacious nature of the assumptions as to why military health services exist and what they do, which has led to the ADF health services’ treatment mission being the only one to be recognised as such and resourced accordingly.

Conclusion

Since the mid-1970s, ADF health policy has generally been premised on assumptions in lieu of the three elemental yet intrinsically linked missions of military health services identified by Butler nearly a century ago. Besides the ‘treatment service’ mission common to most civilian health services, military health services are also required to enable operational capability across all three environments and facilitate the transition of military personnel to the civilian community. Performing these three missions requires an occupational health-based strategic model.

However, commander dissatisfaction within the ADF, and community disquiet regarding ex-serving members, indicates that these assumptions have led to military health services that have not been fit for purpose for some time. With the end of Australia’s Middle East operations after 20 years, there is an urgent need for fundamental reform of the ADF’s health services, in particular ensuring that their non-deployable assets can effectively support future Indo-Pacific operations, most of which will be conducted from bases on Australian soil. These reforms also need to ensure that the health services for ex-serving members begin when they first enter the ADF, with a focus on reporting and preventing avoidable work-related illness and injuries, and on effective workplace-based treatment and rehabilitation.

For reasons of space, references included with this article have been omitted. A copy of the article complete with references is available upon request