- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, RAN operations, Ship histories and stories, WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

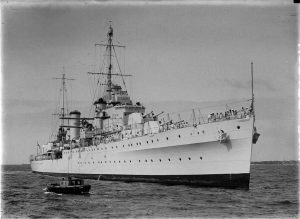

- HMAS Hobart I

- Publication

- March 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

As told to our Editor by Cyril Rayner

The Australian Navy started the war with three relatively modern Modified Leander Class light cruisers. Of these fine ships much has been heard of the loss of HMAS Sydney and HMAS Perth but much less of their surviving sister HMAS Hobart. This story, by now 93 year old Cyril Rayner, was related to our Editor in November 2013, Cyril recalls his war-time service much of which was in Hobart which, being skilfully handled, survived many near misses and one near fatal hit.

To say that Cyril George Rayner was born with salt water in his veins is not too great an exaggeration as he was born at the famous naval town of Chatham on 10 January 1920 where his father, a sergeant in the Royal Marines, was based. When the family later migrated to Australia, his father found work at Garden Island Dockyard (GID) and Cyril’s older brother Reginald (Reg) gained an engineering apprenticeship at GID. Reg later joined the RAN as an engineering artificer. Not to be left out Cyril joined the Sea Scouts and eventually enlisted in the RANR as an Ordinary Seaman where he undertook weekly training at the Reserve Depot at Rushcutters Bay.

Mobilization of the Reserves

With the outbreak of war the RANR was mobilised and, on 6 September 1939, Cyril reported for duty at the Reserve Depot and was entered into the books of HMAS Penguin II. Cyril and a few other Reservists who possessed uniforms were brought before the well known LCDR Alexis Albert, RANR and as there was a waiting list for entry into Flinders he detailed them for sentry duty at Spectacle Island looking after ammunition and stores and at Cockatoo Island being responsible as sentries for ships under construction and repair. After a few weeks he was then sent by train, changing to the Victorian gauge at Albury, with many other youngsters to Flinders Naval Depot (HMAS Cerberus). Here he undertook basic training and qualified as Gun Layer 2nd class and acquired the nickname ‘Stormy’. Cyril would not have been lonely as uncle Reg, now a Chief ERA, was also at FND awaiting posting to HMAS Australia, where he was to serve throughout the war. His father George, who had also been mobilised as a Warrant Officer RANVR was at hand helping to prepare about forty other more senior citizens, mainly retired Royal Marines, who had returned to the colours and would mostly find themselves as parade ground drill instructors of new recruits.

In December 1939, 19 year old Cyril was posted as the one and only naval representative to the Adelaide Steamship Company passenger/cargo liner MV Manunda which had been fitted with a single ex WW I 4-inch gun. In these early days of war with this token armament Manunda continued unescorted on her normal peacetime route from Sydney to Fremantle via Melbourne and Adelaide and then returned by the same ports. Able Seaman Rayner found himself in charge of the ship’s armament and responsible for drilling two guns’ crews, one composed of sailors from the upper deck and the other of stewards. He was assisted in these duties by the ship’s bosun and had to think quickly when the bosun’s friendliness turned into unwanted attention. After all these years Cyril has retained notes of the amount of practice ammunition expended as he drilled the gun crews on passage where they would stop for a short duration and fire at a floating target which had been made on board. In May 1940 when Manunda was requisitioned as a hospital ship, the gun was removed and Cyril found himself back at Cerberus. He was shortly selected with 15 others for Officer Training; six months later passing out of OT Class No 3 he was appointed to Penguin II awaiting a sea posting.

First ship HMAS Hobart in the Med

On New Year’s Day 1941 Cyril proudly put on a new uniform as Acting Sub-Lieutenant (Probationary) RANR and early the next month joined HMAS Hobart, then refitting at Cockatoo. With the majority of the ship’s company on leave Cyril’s welcome on board was far from ideal, he was largely ignored and given a copy of KR&AIs to keep him busy for the first couple of weeks. Another disadvantage of junior rank was that there were not enough sleeping berths for all 700 men on board and the new Acting Sub was required to sling a hammock in the Wardroom Flat, always being given a friendly nudge by passing sailors to ensure the occupant did not sleep too soundly. But it was not long before Cyril found acceptance and the ways of shipboard routines. Then there was a flurry of activity as they were off to the Mediterranean to relieve their sister ship HMAS Perth which had sustained damage during the evacuation of Crete. In attempting to transit the Suez Canal, Cyril first experienced the perils of war in navigating through enemy laid mine fields and attacks from German aircraft. While these missed Hobart they hit the troopship Georgic and another ship which caught fire; Hobart lowered all her boats in helping take off these crews and providing medical assistance. Later Hobart joined the 7th Cruiser Squadron based on Alexandria providing support during campaigns in the Levant and North Africa, all the time dodging Axis bombs and torpedoes from aircraft as well as the threat from U-boats. It was during this period that HMAS Parramatta was torpedoed and sunk with heavy loss of life. Hobart was ordered to return to the Pacific in December 1941. At this time with a true baptism of fire, Cyril was awarded his full watchkeeping certificate.

South China and Java Seas

Hobart returned briefly to Fremantle before making for Singapore in January 1942 then in the midst of a Japanese invasion. Hobart joined other ships under the command of Commodore Collins in an attempt to intercept enemy invading forces. All the time avoiding enemy aircraft and often making for cover provided by rain squalls, merchant ships were convoyed into the relative safety of the Indian Ocean. While refuelling at Tanjong Priok from a Dutch tanker the ships suffered a determined attack by 15 Japanese dive bombers. While the ships were sitting targets only one bomb struck the tanker and Hobart escaped but with minimum fuel. Hobart later joined with Dutch forces in an attempt to cut off the Japanese who were intent on invading East Java. The Allied naval forces were divided into two groups with Hobart being in command of the Western Strike Force and Admiral Dorman in charge of the Eastern Strike Force. During this period 13 separate air attacks involving 109 enemy aircraft were recorded in one day. The Western Strike Force somehow missed the Japanese fleet but the Eastern Strike Force met the full brunt with disastrous consequences including the loss of Perth. With further resistance unlikely to be effective, given the overwhelming opposition, the remaining ships were ordered to Padang to take aboard as many evacuees as possible. The ships made this shallow port under cover of darkness and took onboard about 2,000 refugees, mainly women and children, from Singapore and transported them to Colombo.

Hobart returned via Fremantle and securely moored in Sydney Harbour on 4 April 1942. This was then a period of frantic repair after the ravages of many months of almost continuous wartime operations. Here, Hobart was fitted with a new secret weapon, Radar, complete with six operators who had been given a crash course into its mysteries. There was even time for a belated Christmas party for the ship’s company and their families. On 1 May in company with Australia, Hobart put to sea bound for the Coral Sea to join with the might of US aircraft carriers and for the first time appreciate the advantage of friendly air cover. Task Force 17.3 which included the two RAN cruisers was detached to intercept a Japanese invasion force bound for Port Moresby and, while they came under air attack with bombs and torpedoes the ships were unharmed and the Japanese ships returned to Rabaul. To add insult, American B17s which had been dispatched from Townsville to attack Japanese ships had less than the desired training in ship recognition and bombed our Task Force; thankfully their aim was on par with their recognition. The Task Force with its new radar had however given good account of these improved anti-aircraft capabilities with ten Japanese aircraft failing to return.

In May 1942 the ship returned via Brisbane and the next month the ever popular Captain Harry Howden, RAN was relieved by Captain Henry (Harry) Showers, RAN. Australian naval forces was now involved in providing a screen to the north east of Australia while US naval forces was located east of the Solomons. In July, Task Force 44, which included Australia, Canberra and Hobart, sailed from Brisbane to New Zealand where they refuelled and joined with Task Force 61, this included the battleship USS North Carolina and three carriers. This fleet then proceeded north to recapture the Solomons. On 7 August after a shore bombardment, the first wave of troops waded ashore on Guadalcanal. The same morning a radio report from Australian coast-watchers warned of approaching Japanese aircraft and these were picked up on Hobart’s radar. The Japanese were met by devastating fire from US fighter aircraft and the fleet below. This was followed by another raid in the afternoon which was again repulsed. Further concerted attacks occurred the next day when one destroyer and a transport were lost but the Japanese also lost 20 aircraft.

On 9 August the fleet was deployed around Savo Island with Australia, Canberra and USS Chicago patrolling the southern passage and with Hobart and USS San Juan guarding the centre passage. Three further US cruisers were guarding the northern passage. In the early hours of the morning a Japanese cruiser squadron penetrated the southern passage and crippled Canberra and the three US cruisers from the northern passage. While distant gun flashes were evident, this action was unknown to Hobart until the following day. After the engagement, the remaining cruisers and destroyers withdrew to Noumea where they refuelled and re-ammunitioned. The ships later returned to provide a defensive screen for the US carriers operating against Guadalcanal. At the end of August part of the task force, including Hobart, was withdrawn to Sydney for repairs.

The Coral Sea and Solomons

After refit Hobart was based at Dunk Island inside the Barrier Reef which provided excellent natural torpedo defence and provided an opportunity to stretch our legs ashore and play sport. There were several months of dull routine with ten day patrols into the Coral Sea, followed by three day rests at Dunk or Palm Islands. It was during this period that beer became available from the stores ship Merkur with two bottles per day being issued to all hands when in harbour. In March 1943 Task Force 74 was formed comprising the cruisers Australia, Hobart and Phoenix, seven US destroyers plus HMA Ships Arunta and Warramunga. The Task Force at last free of the Reef, joined with the 7th Fleet at Espiritu Santo on 16 July. A few days before this on 1 July there was cause for minor celebration as Cyril was promoted to Lieutenant (Provisional) RANR.

After a patrol to the west of New Hebrides, which had been in clear weather with slight seas, the flagship Australia, Hobart and three US destroyers were returning to Espiritu Santo. The ships were in defence watches (four hours on and four off) and steaming at 23 knots under a zigzag plan. Australia was in the van, followed at 600 yards by Hobart, with the destroyers in a standard anti-submarine screen around the cruisers, one 2,200 yards ahead and the others at 2,700 yards distant 60 degrees on each bow. On 20 July at about 18:45 the sun had set and it was getting dark, the officer of the watch in Hobart, the newly promoted Cyril Rayner, could be well satisfied with his lot, expecting a run ashore the following day with the attraction of seeing American nursing sisters. But there was a mighty explosion as the ship was hit on its port quarter, machinery went dead, all lighting was lost and the 60 ton Y turret was lifted off its mounting with its guns pointing at crazed angles. The OOWs urgent calls down the voice pipe to his Captain went unheard, the Executive Officer, CMDR James Walton, RAN, lay seriously wounded, but the situation was calmed as the normally taciturn First Lieutenant LCDR Christopher Johns, RN, who happened to be on the Bridge at this time and quickly took charge until the Captain’s arrival.

LCDR Johns ordered stop engines, and action stations, and later made contact with damage control parties to help assess the situation. With the Captain on the bridge permission was obtained to fire starshell to illuminate the horizon but no contacts were observed. The engineering staff worked tirelessly in restoring emergency services. The ship, with two of its four propellers and its rudder blown off in the explosion and now listing to port, was able to restore some power, sufficient to make headway. Using one propeller at fixed revs and the other at variable revs to provide direction, a speed of about 7 knots was attained. In addition a large steel cable was placed around the gunwale to help secure the stern section. Casualties resulting from the explosion were 14 men killed, including a young USN liaison officer, with a further 16 wounded. The torpedo had missed the after magazine by six feet; if this had been penetrated it is doubtful if the ship would have survived.

A later report by the Commanding Officer of Japanese submarine I-GO11 confirmed that she had fired a pattern of torpedoes at the Australian cruisers when at extreme range of about 10 miles, with a running time of 12 minutes. These were intended for the lead ship (Australia) but only one found its target (Hobart). For unexplained reasons, possibly having no further torpedoes, the submarine retired. Hobart limped off supported by screening US destroyers, and next day went through the grim task of committing the dead to the deep. That evening they met with US tugs who assisted the ship in passing through the Bougainville Strait. Early the following morning, 22 July, they were able to find the safety of anchorage at Espiritu Santo. Hobart was not a lone casualty with a number of ships suffering similar damage including two USN cruisers and surprisingly another near sister ship HMNZS Leander, which had been badly mauled by a Japanese cruisers a week previously. Vital support was soon forthcoming from the Repair Ship USS Vestal including the use of then novel underwater cutting and welding equipment. A USN Constructor Officer who examined the damage said: A Nip torpedo makes a hole 60 feet by 30 feet and you are true to pattern. The USN repair group worked tirelessly around the clock including 10 divers who worked for over a week cutting away, repairing and replacing torn plating.

A Board of Enquiry was established onboard Hobart on 22 July under the presidency of Captain Harold Farncomb, DSC, RAN assisted by two other officers from HMAS Australia. Cyril gave evidence to the Enquiry. In summary the Board found that the cruiser was in all probability hit by one of a pattern of standard Japanese 21-inch torpedos fired by an unknown enemy submarine firing at extreme range and that the remainder of the pattern passed astern of Hobart. The two cruisers and the three screening escort destroyers, which were all fitted with radar, had no knowledge of any surface contact and, that because of the speed of advance, sonar was ineffective. The officers and men of HMAS Hobart acted appropriately and the high degree of professionalism especially that displayed by the Engineering and Damage Control parties was of great credit and helped save the ship from further disaster.

With temporary repairs completed Hobart sailed from Espiritu Santo on 21 August being able to make passage at 12 knots accompanied by Arunta and Warramunga and safely made Cockatoo Island Dockyard for more extensive repairs. The devastation caused by a single torpedo would keep Hobart out of the front line for over 12 months and it was not until 7 December 1944 that she recommissioned and once more returned to the Pacific campaign.

Return Home

There was some well deserved home leave and during this period on 5 October 1943 Cyril took the plunge and married Beryl (nee Dickson). They set up home sharing a flat at Milsons Point. But married bliss was interrupted when in December 1943 Cyril was posted as First Lieutenant of the Bathurst Class corvette HMAS Fremantle, then operating on convoy escort duties between Darwin and Thursday Island. Later the next year, he had a short time at home posted to HMAS Penguin, but this again was not to last as in August 1945 he was posted to the large PNG shore depot HMAS Madang. Here he was sent to assist with port operations in remote Langemak Bay, a sheltered harbour on the north east coast near Finshhafen, which was extensively used during WW II military operations. With the war drawing to its close, Cyril returned once more to Rushcutters Bay for demobilisation on 8 November 1945. A new life waited Cyril this time far removed from the sea and the dangers of war. This was in the field of accountancy which surprisingly would later take him for brief visits to PNG. He would however never forget those days when Hobart skilfully survived all that the Axis forces could place in her way.