- Author

- Kingsley Perry

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, History - WW1, WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

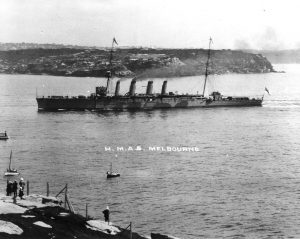

- HMAS Sydney I, HMAS Melbourne I

- Publication

- June 2016 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Kingsley Perry

George Henry Iles was born at Norwood, Surrey on 11 December 1883 and later joined the Royal Navy where he became a cook. On 14 October 1912 he was amongst a large number of RN personnel lent to the RAN, helping crew its new ships fitting out in British yards. On the day she commissioned, 18 January 1913, he was formally posted as a Leading Cooks Mate to HMAS Melbourne and later promoted to Acting Chief Ships Cook and finally to Chief Petty Officer Cook. He served in Melbourne throughout the Great War until 23 May 1919. Following a brief stint ashore he joined HMAS Australia on 20 October 1919 and was in her until 6 December 1920. Another short shore posting followed before passage home and reverting to the RN on 4 September 1921. We know little else about him other than he was married to Hannah: we are unsure if she came to Australia.

George Iles was a senior ship’s cook in HMAS Melbourne throughout the First World War. He produced reminiscences of his time in the ship in the form of a diary which provides an interesting insight into life in the ship and its part in the war. Most history is written on the reports or reminiscences of the people in charge – the overall picture. Sometimes it is interesting to read reports from the lower ranks and to look, as it were, under the covers.

He wrote a diary of sorts he called ‘My reminiscencies [sic] of Four and a Quarter Years of War’. Although in diary form, it may have been written or at least transcribed after the war. It is in ink, uniformly throughout, and in fair handwriting. It has been bound and is kept in the State Library of New South Wales.

Melbourne was always on the periphery but did not have an active role in the First World War inasmuch it was not involved in any naval engagements or battles. Little is written about her, although there is a ship’s history in the excellent book aptly titled The Forgotten Cruiser – HMAS Melbourne 1913-1928 by Andrew Kilsby and Greg Swinden, published in 2013. While Kilsby and Swinden have consulted widely with an extensive bibliography including a number of diaries, that of Iles was then unknown to them.

The diary’s title page summarises the ship’s war history as including the capture of Samoa, Nauru and German New Guinea (August – September 1914), convoying Australian troopships to Port Said (September – November 1914,) the sinking of the Emden by HMAS Sydney (November 1914), patrolling off North America and West Indies (November 1914 – August 1916), patrolling and convoying in the North Atlantic (August 1916 – November 1918), the surrender of the German Fleet (November 1918), and the return to Australia (25 February – 26 May 1919).

In many respects the author follows the format of a report of proceedings – where the ship was or was going to, and what it did when it got there (mostly bunkering). Although there are of course many references to what was happening in the ship, there is less than might be expected about the living conditions or what was going on in the messdecks. There is no reference to any friends or shipmates. Nevertheless, it makes for interesting reading, particularly when reporting on the more well-known pieces of history in which the ship was involved.

Melbourne was an important element of our first fleet that sailed proudly into Sydney Harbour in October 1913 with her better known sister HMAS Sydney. But our author does not dwell upon her arrival or the fact that of her peacetime complement of 390 about half were on loan from the Royal Navy, all being under the command of Captain Mortimer L’Estrange Silver, RN. In fact all the cooks (like Iles) and stewards appear to have been Royal Naval ratings – does this say something about the standard of colonial catering in these times? Another important factor about the ship that only rates a mention in the amount of time spent bunkering is that she was coal fired, which meant constant evolutions of coaling ship and cleaning up afterwards. The largest department was not seamen manning her weapons but stokers, of which she had more than one hundred.

Departure from home

The most dramatic part of the whole diary is the excellent description of the ship’s departure from Sydney with Australia on 3 August 1914:

As we groped our way forward in the darkness, the canopy of heaven above and the deep waters beneath, the silhouettes of the ocean greyhounds were symbolical of Britain’s might, and Australian prowess…never before in history had our vast Empire had reason to feel so proud of England’s sure shield as it was on this memorable day…the mighty steel walls of Britain’s Navy had been called upon to protect not only the free thinking nations of the world, but the whole of Humanity.

Melbourne then spent a couple of months on patrol in the Pacific, trying to find some part of the German Colonies to bombard or part of the German Pacific Squadron to sink. It accomplished neither. She was at Rabaul on 15 September when news was received of the well known disappearance of the Australian submarine AE1. Iles tells us: there were several theories, the most likely being that she had struck a submerged coral reef whilst about to return to harbor, a theory that persists to this day.

In October, Melbourne was called on to escort Australian and New Zealand troopships to the Middle East. On the way to Albany they passed many of these ships: it seemed the side near to us was crowded with Anzacs waving handkerchiefs to us as we sped past them. Melbourne was the first warship to arrive at Albany, and: one by one the transports continued to arrive all through the night forming lines of fine ships as they anchored in position. The impressive escorts the armoured cruiser HMS Minotaur and the battlecruiser IJNS Ibuki joined and HMAS Sydney arrived on 31 October, and on the following day he describes the scene when there were twenty-six troopships and four naval escorts in view:

one of the most memorable days in Australian history – this great assembly of ships began to move – the day was in keeping with events, a cloudless sky which allowed the sun to shine in all its brilliancy, just a light breeze was blowing, and the sea was ripless and this great and representative assembly of men and ships were on the eve of taking farewell of their country, the land of their birth, setting out on a task they knew not where, or how long it would take to accomplish.

While not mentioned in the narrative it is historically important that when Minotaur was unexpectedly detached, as the next senior ship Melbourne was placed in charge of this great Anzac convoy proceeding to the Middle East.

The sinking of Emden by Sydney on 9 November is recorded with his captain: became very frenzied because he could not himself proceed to intercept hostile warship, but he was prevented from so doing on account of his immense responsibility of being in charge of convoy and its safety, and he had to perforce remain with convoy, against his wish……. and each and every one was very excited over impending events and keen disappointment prevailed because we could not go. The news of the sinking of Emden was: great and glorious news and it was a great sight to witness the excitement that it caused among our men. The captain permitted “Splice the Mainbrace” – Sydney done the work, and Melbourne drank the tot, which caused much amusement to the two ships concerned.

All the same, Melbourne missed out on the glory.

Escort duties on the Atlantic and West Indies

Melbourne carried on with her escort duties as far as Colombo, and continued to the Red Sea, Suez, Malta, Gibraltar, and then into the South Atlantic and the West Indies. This was quite uneventful. His diary notes visits to many ports and meetings with other warships, but no naval action. At the end of 1915, he reports: altho our present duties of protecting trade routes were very nice, it was becoming very monotonous, and we all desire change.

Christmas 1915 was celebrated at sea (on 27 December, when men returned from leave). We have some feel for what occurred but there is no specific mention of the important part played by the cooks:

the interior of the ship and all the messes had been gaily decorated, photographs of all the best girls, which had been carefully preserved were on this day given prominent places on the table and bulkheads etc etc, each and all carefully scrutinizing all the fair and pretty faces, that were now exhibited for the first time maybe…dinner consisted of chickens, turkeys sausages, hams, green peas, potatoes, plum pudding and sauce, mince pies, dates, figs, mixed nuts, biscuits, chocolates, lime juice, cigars, and cigarettes, plenty of each item being freely served out.

The ship continued her patrols and drills throughout the Atlantic, visiting numerous ports and meeting up with many warships (including Sydney). Iles is quite thorough in reporting on the ships and what they did and where they were going. There is little reference to news from home. The outcome of the Battle of Jutland was noted on 31 May, but without comment.

Although he clearly enjoyed this period, particularly in the West Indies, they were ready for home as he notes: one and all of us were most eager to go to England to enable us to take a more active part in the Great War. Eventually, on 28 August 1916, Melbourne departed from Bermuda to join the Grand Fleet for operations in the North Sea.

Joins the Grand Fleet

The ship arrived at Plymouth on 7 September, with the good news that all crew were granted three weeks’ leave. Many of the sailors with family links, especially those from the RN after several years away took the opportunity to re-unite with their families. We know nothing of Iles family relationships other than he tells us he had: a beautiful and rainless 21 days in Cornwall (without saying with whom, if anyone). At this time the highly efficient and popular Captain Silver who had earlier contracted malaria sought to be relieved as his eyesight was failing. His replacement was Captain Eric Fullerton, DSO, RN. Then on 6 October: we arrived off Scapa Flow, for this our first introduction to the Greatest Fleet of warships in the world, second to none either in ships, or men, filled us with pride.There is some further detail about the ships and arrangements and harbour security.

The spectacle of the ships was clearly impressive: away on our port beam could be seen a large assembly of warships, the likes of which we had never seen before at least many of the more modern of them and on 1 November: at daybreak we were able to witness for the first time the Great Fleet at sea at least as much as we could see of it because the whole of the fleet that were now at sea covered such a vast area that it was quite impossible to view them all, but as it was there were numberless ships of all classes and description spread upon the ocean in every direction as far as the eye could see.

Then follows a series of exercises and drills, mostly in inclement weather in the North Sea, often in company with HMAS Sydney. The loss of two sailors overboard on 21 December is reported: neither was ever seen again, and no lifeboat could ever live in such a sea, and we were not allowed to stop our engines whilst at sea under no consideration, for fear of an enemy submarine being in the vicinity. Mention is made of the activities of other ships of the fleet with a description of the dramatic collision between the destroyers HM Ships Hoste and Negro when both sank with all hands lost, although he did not witness it.

Christmas 1916 finds Melbourne at Rosyth – a lecture by the Commodore, and: greetings from Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet, the King (and of whom I should have mentioned first; apologies) Rear Admiral Battle Cruiser Squadron, Australian Naval Board, High Commissioner, etc etc. all of which were reciprocated, then church, then we had a sumptuous repast, consisting of poultry, of various kinds, and everything it was possible to have, nuts sweets biscuits, Xmas pudding etc etc, all except anything alcoholic.

On 27 December they were back at sea for exercises for a month when the ship left for an extensive refit at Liverpool: which meant an unlimited amount of leave for the boys. The diary is then compressed until Melbourne rejoins the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow on 19 June. The ship is at anchor at night on 9 July when: a most curious explosion was felt, not a loud report, but that peculiar heavy thud which accompanies a great explosion. Within a few minutes it was learnt that the Dreadnought battleship HMS Vanguard had sunk (an accidental magazine explosion caused the ship to sink with heavy loss of life). Although in the same harbour, it was four or five miles away. No lights were visible: but far away in that direction could be seen on the surface of the water, a long narrow irregular red glow,which was afterwards discovered to be oil burning on the water.

Exercises continued, but there was no warlike action involving Melbourne. The diary continues with entries on most days, detailing what the ship was doing, and what others were doing. He enjoyed: lectures given by the Captain – one on his own wartime experiences, and another on astronomy. Otherwise the diary for the next 18 months or so settles mostly into a routine report of proceedings.

Then on 11 November 1918, the exciting news that the armistice had been signed: the news came through the Fleet like a bolt from the blue. The celebrations, he tells us, were magnificent. The Admiral of the Fleet ordered “Splice the Mainbrace” and leave was given from 1 pm until 5 pm, when an extra issue of rum was given. Much celebrating for quite some time. He writes at some length about the surrender of the German fleet at Scapa Flow, and then reports on the ship’s transit to Portsmouth on 30 November where she remained until 6 March 1919 with HMAS Australia and HMAS Brisbane.

Homeward bound

On 6 March they began their cruise home, visiting a number of ports on the way. Arriving at Sydney on 21 May 1919, the first time in this port since 17 October 1914. The ferries, motor launches and steam boats lined our course, and rousing cheer upon cheer and coo-ees were sent up continually upon our return and so under such an enthusiastic welcome we made our way to Garden Island… As soon as possible the Governor-General came on board Melbourne and personally welcomed our return to Sydney and Australia after having done our duty. On the following day: a banquet was given at the Town Hall in our honour and invitations extended to all officers and men, many speeches were given and the event was a huge success.

On 26 May the ship arrived at Port Phillip. At this time Melbourne was the temporary Federal capital so there was a long list of distinguished visitors including the Governor-General – Lord Denman, the Prime Minister – Mr. Fisher and the Minister for Defence – Senator Millen. The author says here: a similar welcome as at Sydney awaited us and a most enjoyable time was spent by all. The ship’s company proceeded on extended leave and so, he notes: ended a glorious and historical career in the pioneer Australian man-o-war and though bloodless she had done her duty nobly and well, for whether you be at grips with the enemy or patrolling the sea communications it is all a duty in war. He tells us that: during hostilities the ship had travelled approximately 145,000 nautical miles – not too bad a record as prior to the war she had only steamed 25,000 nautical miles. Melbourne served honorably in peace and war; while no shots were made in anger she served in many war-zones and helped preserve Allied superiority. Eight of her ship’s company died during her war service and many others were injured.

And so ended George Iles’s reminiscences. All in all, the diary gives an interesting insight into the ship and its activities, although it reflects little of George Iles’s personality. It does show how life at sea in the Navy was mostly routine, certainly not necessarily always one of adventure and action. Although he was not involved in any naval action, he was justifiably proud of his contribution to the war effort.

The diary, or reminiscences, occupies some 312 pages, all handwritten. It provides a good chronology of the ship’s activities during the war, and is one more example of how so much of history, insignificant though it might be, can be hidden in the writings of those who were there, regardless of rank, role or status.