- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- RAN operations, Post WWII, Ship History and Story Videos

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Melbourne II

- Publication

- June 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By John Ingram

‘Oh, hear us when we cry to thee, For those in peril on the sea’.

Some of the immortal words of the Naval Hymn composed by the Revd. William Whiting after his own brush with death in a violent storm in the Mediterranean Sea in 1860. These lyrics encapsulate so poignantly the events of June 1981 when two units of the RAN, ably supported by FAA aircraft, located and saved 99 men, women and children from a watery grave in the South China Sea. This is the story of the night recovery of ‘MG 99’ or HMAS MELBOURNE Group 99.

Fast backwards 40 years to June, 1981: HMAS Melbourne, flying the Flag of RADM J.D. Stevens and under the command of CDRE Mike Hudson RAN, is steaming south from Hong Kong with HMAS Torrens (CAPT Mike Rayment RAN) to participate in Exercise STARFISH 81. Both ships have been deployed for exercises, initially with the USS Midway Battle Group in the Indian Ocean. Standing between STARFISH 81 and arrival home in Sydney are scheduled visits to Singapore, Darwin and Brisbane with the annual Admiral’s and Departmental Inspections on passage south. All fairly routine one might think, but events are about to change dramatically for all concerned!

Vung Tau harbour was well known to the RAN, especially those who served in the Fast Military Transport HMAS Sydney and her escorts in the period 1965-72. It is from this location and many others along the Vietnamese coast that countless thousands of refugees fled in tiny boats seeking a new start in another country. By 1981 the war is six years in the past but the misery lingers for most Vietnamese.

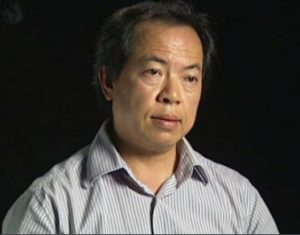

Meanwhile, in Can Duoc, Long An province in the Mekong Delta near Saigon, Nguyen Van Tam, affectionately known as ‘Tam’, the 40-year-old skipper of a 13.7 metre fishing boat, Nghia Hung, (named to honour his two sons), prepares his reconditioned craft for a one-way passage. Local Communist officials have directed him to embark 99 fellow Vietnamese, including his wife, seven children and two brothers.

But first the passengers, aged from just seven months to a 65-year-old grand-mother, are stripped of all valuables by corrupt officials. Some, such as Nguyen Thi Hong Van, aged 30, daughter of a Saigon University professor, is making her fifth attempt to flee. Four previous attempts failed through betrayals resulting in beatings, detention and further payments to ‘organisers’ bent on extracting every last dong from her and family.

After 17 months of planning and with refugees, including ethnic Chinese, the vessel departs the muddy waters of Can Duoc on 18 June in the early hours at around 0130. Conditions onboard are incredibly cramped; water, diesoline and food are severely limited; communist officials decree that just 100 kg of rice and twelve bottles of soy sauce are sufficient to feed the entire boatload for the estimated seven-day passage to Singapore.

Initially weather conditions are favourable and, with good visibility, they pass Vung Tau at 0500 just as dawn breaks. Tam is able to clear the harbour at Cap Saint-Jacques and set course south in the East Vietnam Sea using his basic magnetic compass. His plan is to pass to the west of Con Son Islands initially then to keep well to seaward in the Gulf of Thailand as he has heard tales of the vicious pirates raping, pillaging and murdering refugees in these waters. He is determined his passengers and family will not suffer the same fate as has befallen countless numbers since 1975.

As a postscript, the UNHCR estimate 300,000 Indo-Chinese refugees lost their lives at sea fleeing from Communist regimes 1975-1990.

The first night and day pass without incident; Tam estimates the 20 HP diesel engine has propelled his 14 tonne 3-metre-wide wooden vessel at an average speed of 8 knots into an increasing sea, swell and headwind. So far, so good; 200 nautical miles behind him, 500 ahead if he is to take the direct, open-sea route to Singapore and freedom. There’s an air of excitement onboard despite the appalling congestion. The Con Son Islands are now astern; landfall should be Singapore Island in five days.

With the grossly overladen boat now in exposed open waters the wind increases alarmingly. By mid-afternoon on 19 June Tam estimates it is Force 7-8 increasing. He is reluctant to turn downwind and reverse his course as that would admit defeat. The sea state worsens as does the swell; sea and sky merge in a frightening grey salty melange of fear; infants cry, some scream for their mothers. Most are sea-sick: unable to move from their cramped confinement vomit spews into the bilge, clogging the filter in the bilge pump which stops. As the blend of seawater, diesoline and vomit accumulates the terrified passengers, almost all of whom have never been to sea before, realise their hopes and aspirations for a new life are in serious jeopardy. Death by drowning is now a real prospect. Buddhist and Christian alike pray in common union, openly and privately, hoping their God will hear their pleas for help in their hour of need.

With the severe tropical storm now in full fury any chance of safely confronting the violence is lost. Fuel consumption is excessive; what little remains is soon contaminated. The overheated engine dies and, despite frantic attempts at restarting, all efforts are in vain. Dehydration becomes a serious issue and drinking water is limited to one cup per person per day. Remaining food supplies are rationed to a single scoop of boiled rice with a dash of soy sauce each day.

Without power the boat is at the mercy of the raging seas. Tam suspects he is being blown eastward towards the Spratly Islands: this may prove fortuitous as it would place them in the shipping lanes linking north and south east Asian ports. Surely, he muses wryly, a ship will come to our aid?

Fast forward 24 hours. Three merchant-ships are flagged down but fail to offer any help. Tam is sure others have sighted their flares and frantic waving but have ignored their obvious distress. Morale sinks further with each incident. Tam decides to keep the very last flare for one final attempt. What that will be and when, he keeps to himself.

Despite moderating weather, the long swell persists. The boat remains intact but hand bailing is taking its toll on emaciated, weakened souls. Heat blisters and saltwater sores from constant immersion in bilge water are further causes of distress. The veteran two-way radio has failed, a victim of flat batteries and salt water ingress. Tam is powerless, his tiny command rolling beam to swell with most of those onboard wishing for no more than a swift death in the South China Sea.

21 June: Melbourne is in Modified Sunday Routine which, in this context, means CDR ‘Air’ (Commander George Heron) has flying operations scheduled involving fixed wing S2G Tracker and rotary wing Wessex 31B and Sea King helos. ‘Below’ (the Flight Deck) the Executive Officer (Commander JO Morrice) and fellow departmental heads (as CDR ‘S’ I stand guilty too) seize the opportunity to work sailors on the Sabbath to ‘clean ship’ after the ten-day Hong Kong visit and to prepare for the aforementioned annual Admiral’s Inspection.

Visibility is limited: Torrens, when not close at hand as Rescue Destroyer while launching and recovering aircraft, is barely visible on the horizon, rolling in the confused sea maybe two miles ahead. Her grey hull blends with sea and sky, the near perfect camouflage. I note rain squalls sweeping the flight deck and the difficulty sailors experience in ranging aircraft.

The Command is well aware that the severe tropical storm has dispersed refugee boats far and wide, hence the decision that Melbourne should provide daylight air surveillance. Even the powerful LWO-2 search radars in both ships have difficulty in detecting wooden craft, especially in adverse conditions. This is where the Tracker excels with its ‘long legs’ (endurance), and big ‘ears and eyes’. As if on cue, the first sighting of the day is by a Tracker, of a tiny boat, well distant from the RAN ships. The Liberian registered MV Karaka, en route to Hong Kong, is vectored to recover the refugees. Whether it is a willing participant we will not know.

At 1807, in deteriorating daylight, Tracker 851 with Sub Lieutenant Dave Marshall in command, Lieutenant Steve Langlands as Observer and Leading Seaman Casey as crew reports ‘a fishing boat on fire, 9 miles to the west of Melbourne with estimated 20-50 persons on the upper deck’. This positions the refugee boat over 200 miles due east of Saigon. This means the boat has been blown sideways some 330 miles since her engine failed, testimony to the might of the storm and a feat topped only by the fact she remains afloat.

It transpires the crew of Tracker 851 had sighted the very last hand-held orange flare fired by Tam. The ‘fire’ report was actually from a tub of burning oily rags strategically positioned on the wheelhouse which generated a trail of dense black smoke, quickly dispersed by the wind.

While the carrier turns into wind to recover Tracker 851, Pedro 15, the Wessex 31B rescue helo, lands momentarily onboard Melbourne to embark the Senior Medical Officer. Torrens is detached at speed in the twilight to stand by the stricken vessel. En route to the rendezvous Surgeon Commander John Anderson is lowered onboard Torrens from Pedro 15 at 1840.

At 1902 the boarding party from Torrens reports an estimated 90 plus refugees but the incredibly adverse conditions onboard preclude a more specific count. They confirm the immobilised state of the engine, the absence of fuel and water, the near depletion of food stocks and that most are suffering extreme seasickness, dehydration and exhaustion. There is no evidence of fire.

Earlier plans for Torrens to embark the refugees are quickly cancelled due to the numbers involved. The Command decision is made for Melbourne to be the host ship and planning is quickly underway to embark what was to become known as MG99 or Melbourne Group of 99 Vietnamese refugees.

With Torrens lying upwind and providing some protection, her Gemini equipped boarding party under Lieutenant Ross Smith and Sub Lieutenant Bob Williams begin the difficult task in the semi-darkness of coaxing the refugees, one by one, into the RHIB. Lighting is poor, especially from the hand-held torches; signal lanterns on Torrens attempt to improve the-situation.

On arrival Melbourne also positions herself upwind and her 33-foot Utility Boat (UB) and Geminis are quickly on the scene.

The refugees are greatly relieved to see the UB and the relative security a more substantial boat offers. Soon a shuttle begins transferring all refugees, seven in each Gemini load, to the carrier’s starboard forward ladder position where the ship’s rolling and pitching movement is deemed to be the least in this confused sea state.

Onboard the Flagship the Executive Department is very busy preparing the means to hoist onboard 33 men, 37 women and 29 children, whose medical condition ranges from barely-able to stand to unlikely to survive 24 hours without urgent medical intervention. Lieutenant Commander Linn Smith MBE RANR, the First Lieutenant, has been tasked to take charge of the seamanship aspects. The wily and experienced No. 1 has devised Plan Alpha, a ‘drifting ladder’ concept in the little time available to overcome the potential dangers associated with having boats alongside a carrier’s heaving hull.

Plan Alpha is soon discarded, however, when it is realised that our soon-to-be passengers are none too keen to attach themselves to a trailing rope ladder at night in the open sea. Nor are we onboard enthused by the thought that we have found them, offered hope but could see them drown or, heaven forbid, attacked by hungry sharks.

Plan Bravo involves a modified helo rescue strop lowered over the ship’s side. In conjunction with the steel boarding ladder affixed to the ship’s hull a process begins whereby each person is placed in the strop and hoisted aboard. Some relatively able-bodied young refugee men make the ascent in the strop alone but the majority elect to be in the arms of a re-assuring sailor. Remarkably, no one is lost or injured and the embarkation is completed at 2145, just 55 minutes after the first person was hoisted onboard.

This highly successful recovery evolution conducted in trying conditions in total darkness was attributed to teamwork at all levels. This included the positioning of the two ships upwind to quell the sea state as best as possible; the leadership and direction of the Executive branch officers involved; the skilful boat handling by the coxswains and crews and, most importantly, the fit young sailors who, time after time, carried or supported exhausted and sometimes unconscious refugees up the rolling ship’s side.

Both ships and their crews performed to the highest expectations that night. The Fleet Commander reported by signal to Canberra that: …in conducting this operation officers and sailors from both ships displayed great professional skill…safely and efficiently.

By 2145 Torrens has completed a thorough check of the abandoned fishing vessel and her demolition team execute the order to sink the craft lest she become a hazard to shipping.

The last person to leave his beloved boat, Nghia Hung, is Tam, clutching the vessel’s compass and brightly polished brass wheel which he has carefully detached. Tam hands his prized possessions to a Gemini crew member; a symbolic gesture to the RAN for saving the lives of all onboard his simple command.

The very next day the interviewing process begins and is to last four days. This labour-intensive task is needed to comply with UNHCR, International Red Cross, and Singapore and Australian Government requirements. Led by Lieutenant Commander Mike Webster, it includes three women who have volunteered to act as language interpreters in Chinese and French.

Mike quickly realises these women are very helpful in establishing an effective liaison between the two very diverse cultures. Use is made of the Navy-supplied translation cards. After a short while confidence has risen to the point Mike is able to form three interview panels which expedite the time consuming and repetitive nature of the task as facts are compiled, sorted and reported to various authorities.

Great care is taken to avoid any sense of ‘interrogation’ by such simple steps as ensuring privacy and detachment; infants are provided with toys to avoid distracting a parent during interview and so forth.

Various arrangements are put in place to occupy the refugees during daylight hours. The men are eager to work ‘part of ship’ assisting in basic maintenance tasks such as chipping, scraping and painting. Women who are without children to care for volunteer to clean showers and toilets, and undertake laundry and food preparation duties. The religious needs are met by making the chapel available for the many Catholic refugees.

Ship tours are especially popular with the children. These activities greatly assist the integration process, break down cultural and racial barriers and are for the common good. At night sentries are positioned on the exposed and windy forecastle to ensure physical security, especially in relation to the children, while the refugees sleep on camp stretchers. Most remain mentally distressed at having left their homeland, relatives and friends. All express profound relief that they have survived the perils of the sea.

On arrival in Singapore Friday 26 June local Quarantine, Health, Security and Immigration officials check the new arrivals. Due to the thorough pre-arrival administration undertaken by ship’s staff these checks are completed without complication. The refugees are assembled onboard to be addressed by Australian High Commission and UNHCR staff then bussed to the Hawkins Road Refugee Camp. Of these, 77 apply for Australian permanent residency status, are accepted and are airlifted to Sydney by QANTAS the following month, arriving ahead of Melbourne’s final return to her home port.

There were lessons to be learned from such a recovery operation, especially in these trying conditions. Melbourne reported these to higher authority so that future incidents might be better resourced. These included improved lighting in RHIB type craft, the urgent need for genuinely waterproof hand-held radios, suitable clothing for women and children etc.

Living conditions onboard for the refugees were cramped, noisy and far from ideal; no-one would pretend the forecastle of an operational aircraft carrier would be anything but difficult especially when launching and recovering aircraft. Melbourne was able to provide medical and dental treatment, good food, potable water, showers and laundry facilities, basic clothing and toiletries, camp stretchers and bedding and, above all, a safe haven with hope for the future.

CDRE Hudson received a letter from the UNHCR Commissioner shortly after the ship’s arrival in Singapore. It read:

I would like to extend to you my congratulations and my gratitude to you for your humanitarian gesture towards refugees in distress on the high seas. Thanks to your actions 99 Vietnamese refugees…were brought to Singapore. I want you to know that our office is aware of the great responsibility you took in doing so. I appreciate the fact that you did not hesitate to save lives.

{Signed} Luise Druke

That all 99 refugees survived is a great tribute to the skill of the skipper Nguyen Van Tam, his tiny fishing boat and all RAN personnel involved in this remarkable recovery operation one night many years ago.

About the Author:

John Ingram served in the RAN for 28 years including six ship postings, in two of which, namely HMA Ships Stalwartand Torrens, he was the commissioning Supply Officer. John was the initial RAN Exchange officer with the USN in Pennsylvania (1974-76) and the RAN’s first graduate of the US Army’s Logistics College, Fort Lee, VA in 1977.

John rues the day the RAN lost its invaluable fixed wing air cover capability. ‘The carrier Melbourne was the first RAN ship I stepped onboard as a starry-eyed Cadet Midshipman in January, 1957, and the last I stepped off as her Commander ‘S’ in 1982, shortly before her decommissioning. It was a sad day for me, compounded by the fact we failed to secure HMS Invincible and a new generation of fixed wing aircraft the following year.’

Having served in South Vietnamese waters in Sydney and Torrens, John had gained a deep respect for this war-ravaged country. Following the fall of Saigon in 1975 while serving on USN Exchange, he volunteered to assist the US Red Cross in the development of a logistics plan enabling the urgent settlement of refugees in a disused US Army camp in Pennsylvania. From 1978 to 1980 he was the honorary secretary of the Indo-Chinese Refugee Association in Canberra. At night and weekends John and wife Janet worked tirelessly resettling displaced individuals and families from hostels into the wider community, locating missing family members, pleading cases for visa status with government departments and so forth.

John sensed that in this 1981 deployment Melbourne would be, in some way, involved with refugees. Prior to departure from Sydney, he had obtained approval for Ship’s Welfare Fund money to be used to purchase toys and essentials not available via the public purse. Immediately prior to this incident while Melbourne was in Hong Kong for R&R, he and Janet had twice visited local refugee camps and distributed clothing, books and money generously donated by the ship’s company. Little did they realise that within days Melbourne would be so intimately involved in saving lives on the high seas.

John resides in Port Macquarie where he maintains his life-long interest in refugee issues. In the 2014 Australia Day Honours list he received the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) in recognition of his voluntary involvement in refugee resettlement, with special mention relating to MELBOURNE Group 99 (MG99).