- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

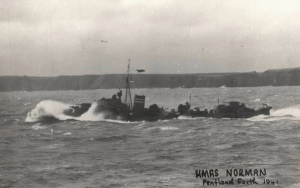

- HMAS Norman I

- Publication

- March 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Peter Nunan

Background

The N-class destroyers operated in many parts of the globe but HMAS Norman was the only one of her ilk to have made an operational voyage to Russia. In October 1941, she proceeded from northern Scotland to Iceland, past Bear Island and Murmansk to the White Sea port of Archangel. Over the next three years, convoys using this route to Murmansk became the focus of public attention in the terms of men, ships and material lost to German enemy action in horrendous weather conditions. Norman’s icy passage remains possibly the most memorable of her wartime activities.

A new Australian destroyer, six British trade unionists, and Winston Churchill combined to produce a notable voyage in October 1941. On 2 September that year in Edinburgh, the British Trade Union Congress set up an Anglo-Soviet Trade Union Council. Two weeks later, in Southampton, Commander Henry Burrell, RAN1commissioned HMAS Norman; his navigating officer was Lieutenant Graham Wright, RAN2. Three weeks later, on 8 October, Churchill, eager to promote Russian links, had Normanand six unionists on their way to Russia.

The delegation’s leader, Sir Walter Citrine3, Commander Burrell and Lieutenant Wright all recorded the voyage in later publications. Norman‘s Report of Proceedings fills in details. Burrell’s Mermaids do Existpublished in 1986, two years before his death, gives one perspective, and Citrine’s autobiography, published in two volumes in 1964 and 1967, provides another. In 2014 Wright also produced his autobiography, the aptly named Putting it Wright, in which he provides a slightly different version to that of his commanding officer. We also benefit from a previous article in this magazine, One of our Destroyer’s Journeys to Russia by George Ramsay, published in December 1988.

Norman’s captain’s evening meal, on 6 October at Scapa Flow during work up, was interrupted by a summons from his superior. Rear Admiral Hamilton ordered him to Seydisfjord, Iceland to embark Citrine’s party from the disabled HMS Antelope. The delegation had previously embarked in the destroyer Antelope but she developed engine problems caused by water freezing in her condensers. The admiral asked if Burrell had the necessary charts. He confessed ignorance, but said ‘ … he would pinch Antelope‘s set if necessary.’ Then he respectfully reminded the Admiral that his new ship, still working up, could in no way be considered battleworthy. This was blandly met with, ‘ … he knew the position, and I was to let him know at what time I wanted the boom gate opened …’

Driving hard through the night, morning fog, and a bright afternoon Norman averaged 31 knots to reach Antelope and transfer the passengers. Sailing at 0800 on 8 October, Burrell steered well clear of German-occupied Norway, and, maintaining best speed of 18.5 knots in rough, very cold weather, they reached Archangelat 1500 on 12 October. On passage, to improve his ship’s readiness, he carried out gunnery practice, and kept the forward gun mount constantly manned. A steam hose, rigged to prevent freezing of the ready use ammunition housing, itself froze.

Wright’s Observations

At this stage Graham Wright was a newly promoted 22 year old Lieutenant and had yet to complete a course of specialisation. He was, however, given the highly responsible job of navigation officer. He relates that as the crow flies the distance between Seydisfjord and Archangel is some 1370 nautical miles but, making a passage clear of enemy aircraft and submarine activity, meant going mostly inside the Arctic Circle north of Bear Island as far as 75 degrees north latitude and increasing the distance to some 2470 nautical miles.

With only the benefit of primitive anti-aircraft radar and, with the prior agreement of Russian authorities, that a lighthouse would be operational for five minutes only on the hour, they made landfall during a snowstorm off the Kola Inlet. After circumnavigating a minefield, they arrived at the mouth of the North Dvina River to take a pilot who spoke no English, beyond port and starboard. They later learned that the minefield they so carefully avoided didn’t really exist.

Owing to the high speed of advance the voyage was extremely uncomfortable, especially for non-seafarers such as the Trade Union Delegation. To escape the vibration of the Captain’s Day Cabin, Sir Walter found some relief in the Chart House below the Bridge, which was heated, and he could converse with the Navigator on progress. Quite a rapport was established between the young Australian and the experienced older man who spoke freely of his mission to gain first-hand information from Stalin as to whether the Russians could hold out against the German offensive before Britain poured aid into northern Russia, which might then fall into enemy hands. If not, an alternative strategy was planned to be implemented before Christmas, whereby the British Trade Unions were to be called out supporting appeasement with Germany.

Ramsay’s Observations

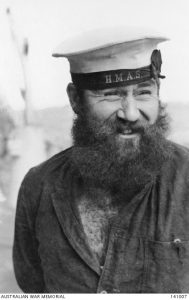

George Ramsay was a 20 year old Perth born junior sailor who had served in HMAS Sydneyand who, together with about 120 of his colleagues, was transferred to form the nucleus of the crew of the new ship Norman. They were the lucky ones who escaped the Sydney/Kormoranengagement. Extracts from young George’s recollections help fill some important gaps.

Into the Barents Sea and passing north of Bear Island, then turning southward past Murmansk, and into the White Sea. On Sunday 12 October, we were met by a pilot and two officials in a very smart motor launch, skippered by a tall attractive lady in a white uniform, who then guided us into the Dvina River proceeding along the tree lined and snow covered shores to berth in Archangel. From our berth, all seemed to be wood – ice – snow, and the settlement reminded me of an old time American army outpost.

This berth was in a bay with a small settlement on the opposite side from the city of Archangel which could only be reached by boat.

A band of very sizeable armed women sentries, probably appearing so under a lot of protective clothing, patrolled the dock area but the local traders eluded them. As we had no Russian money someone soon found out that a bar of chocolate or a packet of cigarettes could barter all that was on offer, which wasn’t much due to local rationing. What we needed was warmer clothing and I managed to acquire a fur hat. It was also so cold that we did not venture ashore much. There was a small canteen-bar but the local beer was awful to drink, and more devastating in results. For recreation someone from the two RN destroyers we found up here Escapadeand Impulsiveproduced a football, and it was hilarious playing in the deep snow.

The ships were later joined by the cruiser HMS Suffolk which berthed further downstream.

Citrine’s Observations

At Archangel, as Sir Walter and his team disembarked ‘ … it was quite clear that he hoped for a bigger ship for his return.’ Burrell was not wrong as the 54 year old Citrine had an uncomfortable voyage. The following excerpt taken from Sir Walter Citrine’s observations provides a useful insight into conditions in one of HMA Ships when working far from home:

At daybreak the following morning, Normanput to sea, and when I awakened the heaving of the ship showed that we were already some distance from land. The Commander had very considerately allowed me to use his day cabin on the lower deck … Every ship has its own peculiar motion and Normanmost certainly had hers.

I went up to the bathroom on the deck above and bathed and shaved as expeditiously as I could because of unpleasant and unmistakable symptoms. I had to return to bed but the pitching and rolling of the ship was so violent, and I felt so thoroughly dejected, that I couldn’t even read. I lay listening to the interminable whirl of the propellers and the swishing of the water near my head. There was only three-eighths of an inch thickness of plating between the sea and us, and one could hear many sounds that would never be noticed in a larger and heavier ship.

The atmosphere was decidedly colder than it had been the previous day and I was literally buried in blankets. Naturally I ate nothing, and the succeeding night could scarcely sleep, and lay listening to the howling of the wind and the battering of the sea against the hull.

[Next day] I staggered up on deck … to find a fresh wind blowing and a heavy swell running, so that I had to walk warily and to hang on to the lifelines which ran lengthwise at shoulder height above the deck.

The crew were Australians and they were a husky and friendly lot. They were clustered about the gun stations and near the funnel trying to escape the biting wind. Everyone wore his balaclava helmet and was muffled up in all the warm clothing he could muster … The weather really was cold and I was told by one of the engineers that the men in the stokehole were wearing heavy coats to keep them warm. It appears that the forced draught was rather strong and the frigid air rushes down on the stokers … The following day, when I went on deck, I was greeted with a swirl of sleet, the decks being wet and not at all easy for landlubbers to traverse … We were now very far to the north, and I thought this was probably the coldest weather we would encounter. We had only six degrees of frost, but, on going to the forecastle, I saw ice encasing the guns, stays, deck and rail … Despite the bad weather it was a pleasure to go on deck, not only for the exhilarating air, but to chat with the crew … They were a keen, alert lot of fellows. At the moment their principal concern was whether they would get any leave in Archangel and how much. What was Archangel like? How much did vodka cost? Were there any dancehalls there? How much was the rouble worth? Did the Russians like night life? Was the vodka very strong? These, and a host of other questions, showed how eagerly the crew were looking forward to having a fling ashore … One grievance these young fellows had was about rum. It appears that there is no rum allowance in the Australian Navy as there is in the British, and on cold runs like this, the crew considered this was a hardship. Certainly they were going through it. Used to the beautiful, mild climate of Australia, these frigid zones put a strain on them. I looked up at the fellow in the crow’s nest and thought he must nearly be frozen. Fortunately these men only have very short spells of duty of about an hour each on lookout.

The engineers weren’t without their troubles either [with fractured water and hydraulic pipes]. But they took it very philosophically, as they said such defects always showed themselves in a new ship …

The wind, which was now abeam, caused Normanto roll a good deal, so much so that one of the officers was thrown the whole length of the wardroom. … That night the weather became worse, and I went to bed early, listening to the sudden angry swirling of the water, the tremor of the ship, and the banging of the sea on her sides … The cold at night was intense, and although I had an electric radiator turned on and an extra blanket on the bed, I had to put my heavy coat on top of these to keep myself warm. I turned in wearing my underclothes and socks, over which I pulled my pyjamas.

The succeeding day the gun turrets, decks and almost every bit of metal were covered in ice. One of the crew told me he had almost passed out with the cold during his four-hour watch. I lay awake until approximately five o’clock, when, suddenly, the bedding shot off the mattress and I was hurled right across the cabin … I knew that we had to expect an unpleasant passage in a destroyer, but I never imagined it could be so bad …

That morning] for a time I stood [on deck] … talking to the men on watch. We had a following wind, whereas the previous night it had been on the beam practically the whole time. It was a sight to inspire confidence to see how the little vessel soared up just as mountainous waves appeared ready to burst over her. There was a really heavy swell, some of the waves rising, I should say, more than fifty feet above the deck. Yet somehow they seldom succeeded in curling over the poop. Forward it was a different matter. Great wave after great wave came over the weather side and swept along the decks. One had to be wide awake to avoid trouble. But the cold didn’t freeze the spirits of the crew who were as friendly and optimistic as ever.

On Sunday, 12th October, while we were at breakfast, the alarm bells began to ring … An aeroplane had been sighted … It was very inspiriting to observe the alertness of the crew as they speedily and calmly manned their posts … The aeroplane … turned aside [so] we never knew for certain whether it was a German or a Soviet machine.

Soon after … we took a Soviet pilot on board, accompanied by two officers, one of whom was an interpreter … They were full of admiration for Norman, calling her a beautiful ship, which in truth she was despite the unpleasant time she had given us.

The destroyer rounded the turn and passed down the delta of the River Dvina, steaming briskly along. At the truck of the mast a figure of an Australian kangaroo had been fixed with a pennant streaming from it and the White Ensign floating below …

Further down the river we drew near the quay and fastened up alongside in the rapidly diminishing light. Very soon an English naval captain came on board, accompanied by a delegation of trade unionists … They greeted us warmly, and regretfully we left our good host, Commander Burrell and the officers and crew of Norman.

Citrine’s party was flown from Archangel to Moscow hedge-hopping all the way to avoid enemy aircraft. At this time, German troops were within 20 miles of the Russian capital. On arrival they discovered Stalin had remained but many of his senior political advisers, who they had hoped to see, had decamped to Kuybyshev some 500 miles further east. The mission was however regarded as a success, leading to increased aid being shipped to northern Russia and a subsequent return mission of senior Soviet officials to Britain.

Burrell’s Leadership

After two days at a rudimentary jetty Commander Burrell decided that as the Russian trip had interrupted their work-up, training should continue. Perhaps also feeling his crew would be better off at sea, rather than ashore in the arms of the local ‘angels’. With the agreement of the resident Senior British Naval Officer Norman sailed on an anti-submarine patrol for two days in some of the coldest weather in the world, inside the Arctic Circle to the Barents Sea. Burrell’s style of leadership, if not exactly appreciated by his crew, was to later take him to command the Australian Fleet and then achieve the greatest accolade as Chief of Naval Staff.

Shortly after return to Archangel, at 1530 on 16 October, Norman was ordered by Suffolk to proceed to Seydisfjord. Off Bear Island came the order, again from Suffolk, to return and from the 19th to the 21st the destroyer was again alongside. Another anti-submarine patrol and an assessment of a possible convoy anchorage as the river began to freeze filled part of the wait for the unionists.

‘A thoroughly depressing town’ was Burrell’s assessment of Archangel. On his only run ashore the captain and his chief engineer passed rifle carrying women sentries before traversing wooden roads. They saw no men, and ‘the women, … shrouded in black, all seemed very old.’ An order in a cafe for fried eggs produced two frying pans each containing four small eggs.

Homeward Bound

Citrine’s party rejoined Norman on 27 October. He describes the return voyage:

After about two hours steaming we dropped anchor and lay to until orders were received for us to proceed on our way.

The following day opened with a bright sun in bitterly cold weather. On going on deck I found that the ice was at least three inches thick and big chunks of it, broken off as we passed through, were forming up some distance behind us. No doubt it would soon freeze over into a solid mass …

This cold of the return leg initially matched that of the voyage to Archangel. Thankfully the seas were kinder. On the bridge a suspicious sighting turned out to be a log. Citrine continues:

I descended to the comparative warmth of the main deck, joining the select party who were warming their hands on the funnel. I was curious to ascertain what the crew thought of Archangel. They held that the roubles were far too expensive and they grumbled that a bottle of Madeira wine had cost them 35 roubles, with the rate of exchange at 48 roubles to the pound. They had resorted to trading cigarettes and chocolate. A bar of chocolate brought 10 roubles, and English cigarettes were much sought after.

The intense cold persisted until the day before arrival. Gunnery practice with a smoke float as target Citrine judged as ‘pretty good.’

We put in at Iceland where the caterers for the various ship’s messes went out hunting for food. I saw them delving into the shops for fish, onions, bread and biscuits … The following day we left Iceland, travelling at high speed … An open boat was investigated and found to be a fisherman; a wisp of smoke on the horizon was monitored until it disappeared.

Arrived off a place somewhere in Scotland, a lighter put off to us and we passed down the ship’s side while the whole ship’s company lined up to give us three cheers which we heartily returned. We left Normanwith a real sense of gratitude to the good fellows who had brought us home in security on a voyage full of interest, despite the rigorous weather.

Burrell’s account adds further details. At 0700 on 27 October, Norman sailed for Seydisfjord. Arriving there on the last day of the month, Normantook on bread and mutton from the Army before sailing at 6.41 a.m. on 1 November. The party disembarked next day at 9 a.m. at Scrabster, Scotland.

Summary

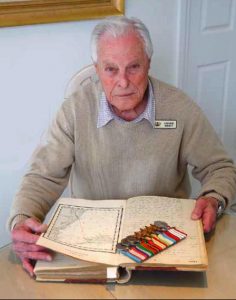

This northern voyage was unique to the RAN in WWII. It made its crew some of the few Australians eligible for the Arctic Star, the last campaign medal of the war. Norman‘s navigator, Graham Wright, was 93 when he received his in 2013, at the same time ex‑Able Seaman George Ramsay, then 91, also received his medal. The captain, who died in 1988, did not live to receive his Arctic Star. The Russians did not forget their past comrades and eventually issued a splendid Russian Convoy Medal, with its striking ribbon, to all Allied sailors involved which included those of the RAN.Commander Burrell also received a black lacquer cigarette box Sir Walter gave him on disembarking. He was grateful, but in 1986 ended his account of the voyage with:

I have yet to learn if the conference in Russia achieved anything, and I still doubt the wisdom of sending out into enemy waters a ship whose only fighting attribute was high speed in retreat.

Naval and merchant ships suffered grievous losses during these Russian convoys with their precious cargoes being delivered at tremendous cost. The heroism, determination and seamanship displayed by all who took part deserved the mark of respect they made in maritime history.

Notes:

- Henry Mackay Burrell (1904-1988) was a highly successful Australian naval officer who graduated from the RANC in 1921 and served in a number of RN and RAN ships during the inter-war period, including as navigating officer of the cruiser HMS Devonshire, during her tour of duty in the Spanish Civil War. Early in WWIIhe was given command of the new N-class destroyer HMAS Normanand in her took a British delegation to Archangel. A variety of other commands followed with promotion in 1959 to Vice Admiral as Chief of Naval Staff when he received a knighthood. He retired from the RAN in 1962.

2.Graham Wright also wrote of his experiences in his autobiography Putting it Wright,published in 2014 when he was 94 years of age. He was greatly assisted in this work by his much younger wife, Marie. Graham Wright excelled academically and was good at sport, he became Chief Cadet Captain and King’s Medallist at the Royal Australian Naval College, all attributes likely to assure a highly successful naval career. His self confidence sometimes placed him at odds with more experienced officers and his fractious relationship with Henry Burrell impacted upon his subsequent naval career. In 1962 he retired from the RAN and after a couple of false starts pursued an accomplished public service career within the Department of Defence.

- Walter Citrine (1887-1983) came from humble origins, his father was a seafarer from Liverpool, but he quickly rose through the ranks of the Trade Union movement. He was General Secretary of the British Trades Union Congress from 1926 to 1946 and from 1939 was also President of the influential International Federation of Trade Unions and, from 1931 a director of the mass circulation Daily Heraldsocialist newspaper. Citrine was favoured by Winston Churchill because of his anti-Nazi views. He had made visits to the Soviet Union in 1925 and again in 1935 and, with Government support, visited Finland in 1940 when Britain was providing aid at the height of her war against the Soviet Union. His 1941 visit to the Soviet Union was part of Churchill’s diplomatic efforts to bring Russians into an alliance against Germany before establishing Arctic convoys providing them with war materials. Walter Citrine was knighted in 1935 and received a peerage in 1947.