- Author

- van Gelder, Commander John RAN (Rtd)

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Queenborough

- Publication

- March 2003 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Friday 21st was a distinctly unpleasant day for everyone in the ship. By this stage a steady routine had been established. With the enormous swell on the starboard beam the ship would roll to port on the approaching swell then almost recover to a vertical state in the following trough before being rolled again to port on the next swell. There was, of course, a sea on top of the swell but this appeared insignificant in relation to the magnitude of the swell.

I have often regretted that we made no attempt to take accurate measurements of the swell height and interval. There is no doubt that the height from trough to crest was in the vicinity of fifteen metres and possibly more. The height of Queenborough’s bridge above water line was 30 feet and we were certainly looking up at the top of the approaching swells at a considerable angle. From memory the interval between crests appeared to be about 200 metres and they were moving at a speed over the ground that would have been difficult to assess. The bitterly cold wind at this stage was about 70 knots and breaking the tops off the seas into white water and salt spray. The clear vision screens on the bridge were being given an unremitting workout. Naturally, venturing out on to the upper deck was definitely not on.

During the afternoon watch the Engineer Officer advised that the inclinometer was registering the ship rolling to port up to 40 degrees. From a ship handling point of view one incident occurred which indicate how critical speed can be in these conditions. Our estimated time of arrival at the Island was calculated as late afternoon Saturday. Therefore, in order to give us some leeway in time, it was decided to increase speed to 20 knots. The consequences of increasing speed were quite remarkable. Whilst steaming at 18 knots, although rolling badly, we were not shipping water across the decks. When speed was increased by just 2 knots it was found that we were shipping water over the forecastle deck edge and it was running across the deck as broken white water about eighteen inches deep. This was a terrifying sight to me as I had no inclination of burying my ship vertically into the Southern Ocean, thus an order to return to 18 knots was rapidly executed.

After wandering around the ship late Friday night listening to the odd creaking sounds being produced by a relatively old riveted hull, I wondered just how hard you could drive a ship from a structural integrity point of view. These were not idle thoughts, since I could recall quite vividly being involved in stopping a leak and shoring up the ship’s side in the forward seamen’s messdeck of HMAS Quiberon during a northerly gale in the Straits of Formosa only a few years previously.

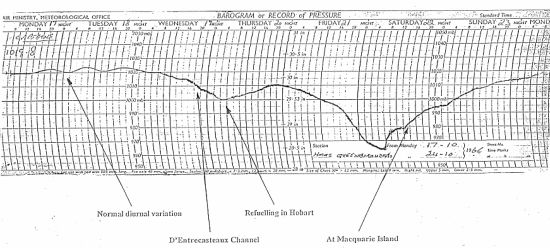

On entering my cabin at about 0100 I glanced at the barograph to find to my surprise that the atmospheric pressure was now down to about 975 millibars and still falling. At this time I had a number of thoughts, in order:

Firstly, this is a crazy situation, however we must press on because it is a medical evacuation after all.

Secondly, just how low can the barometer fall? The rate at which it was falling suggested to me that we were approaching the centre of a depression – and what then?

Thirdly, a vague but real sense of isolation. We were a long way from assistance in these extreme weather conditions.

That night I think I envied my junior sailors sleeping in their swinging hammocks, since trying to sleep on a single mattress aligned fore and aft, under these conditions, required some skill. I had left instructions for the Officer of the Watch to call me at 0600. This he did in the usual and very effective manner by calling down the voice tube. On this occasion, however, apart from hearing the cheerful voice of the Officer of the Watch telling me the time and how bad the weather was I was also treated to a cupful of stale, rusty water into my ear from the voice tube. Not a good way to start a new day! No doubt the offending liquid had been accumulating somewhere in the voice tube plumbing for some considerable time, awaiting the time for the ship to roll far enough to port to dislodge it and surprise some hapless victim (me!).