- Author

- Gladstone, Lieutenant G.V.

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

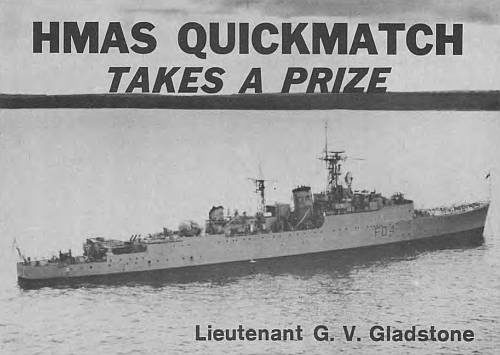

- HMAS Quickmatch

- Publication

- September 1974 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

This article, which was originally published in 1944 in the ship’s magazine, tells the story of the destroyer’s first operation in the Atlantic in late 1942.

QUICKMATCH ENTERED THE WAR at a critical stage. The North African landing had just been made, and our first job was in support of the operation.

Leaving England as an escort to a very large troop convoy, the passage was without interest until the morning of November 30, when information was received that an enemy vessel was being bombed by our aircraft off Cape Ortegal. She was estimated to be proceeding on a westerly course at twelve knots, but beyond that there was no further information.

Despite numerous submarine reports the convoy proceeded peacefully and without excitement of any sort. In the early afternoon of December 2 a ship was sighted fifteen miles ahead of the convoy; the Senior Officer of the escort immediately detached Quickmatch and Redoubt to investigate. Quickmatch was first on the scene and ordered the vessel by light not to attempt scuttling, nor to transmit on W/T. This appeared to have an immediate effect on the strange ship as she stopped engines and, as if more as an afterthought, ran up the Swedish ensign.

Wallowing in a long swell she hoisted a group of flags, stating that she was the Swedish ship Nanking, bound for Buenos Aires. This weak and ineffective attempt at bluff was called when Quickmatch ordered her to lower a boat and send her papers on board for inspection. Playing for time, a reply came back that it was too rough to lower a boat. Both destroyers had been circling the ship, but Quickmatch now closed and ordered the immediate despatch of papers, the order being passed verbally by the ‘loud hailer’. This excellent invention eliminated any previous ideas of stalling.

Pathetically the bogus ensign was hauled down, and replaced by a white tablecloth; simultaneously the vessel commenced lowering a boat.

After a considerable effort the wretched-looking crew got their boat alongside the ship. An officer and six men were hauled inboard, the officer immediately furnishing the information that his vessel was the Italian merchant ship Cortellazzo, bound from Bordeaux to Japan, with six German passengers, and two thousand tons of aircraft machinery. During this period the Senior Officer of the escort had confirmed the identity of the Italian by W/T from Admiralty. Thus ended a most inadequate and unimaginative attempt at deception; perhaps the Master had a dismal dreading of the future, and grave doubts as to the hospitality of the Japanese.

What was to be done with the Cortellazzo? An immediate decision was required and this inevitably fell to the Senior Officer of the escort. In passing, it would not be out of place to remark on the responsibility attached to this most important command: The direction of seven escorts for twenty-three large liners carrying 60,000 troops – influenced by this terrific responsibility, one man had to make the correct decisions. There were three possibilities: to sink the ship forthwith, allowing the destroyers to return immediately to their places on an already inadequate screen; to put a prize crew on board and join up with the convoy; finally, a more desperate, but less secure, move – to coerce the Italians into steaming the ship in convoy.

Weather and the U-boat situation decided the question. Having ordered the Cortellazzo to abandon ship, Redoubt picked up the survivors, and then sank the vessel by torpedo and gunfire. Turning into a rising sea, we increased to maximum speed in an endeavour to rejoin the convoy before dark. It became rough and, of course, cold and wet: first impressions of an HM ship for the Italians could not have been worse: desperately miserable and violently seasick, they must have cursed the German masters who thanklessly consigned them to Japan. The following day the unhappy band were mustered for interrogation. A mixture of English, French and Italian served as a means of ascertaining their stories; all had come from Trieste to Bordeaux, via Monaco, by rail; they were united in one cause only, the hatred of the Germans; who would win the war was of no interest to them; they all lived very much in the immediate present, and were greatly relieved at having been picked up.

With the return of calm weather the Italians ate voraciously, and, in between deck scrubbing and feeding, they conveyed to their ‘hosts’ how much they appreciated ship’s food after Italian standards. The third officer had been a journalist in the Consular Service: his chance to become an efficient seaman had been greatly handicapped by two previous sinkings while on the way to Benghazi.

A few days later our harmless prisoners, a little sadly, walked ashore, escorted by a formidable military guard, who were prepared to use tommy guns, rifles and bayonets if the necessity should arise.

We are an extraordinary people. Many months later the ship was reminded of her part in the Cortellazzo incident by a letter from the Admiralty. Written in that pompous, but prosaic style of all official correspondence, it related the sad story of the loss on board His Majesty’s Australian Ship Quickmatch of one cigarette lighter, the property of one Bundal Luigi, ex-SS Cortellazzo. Mercifully picked out of the cold Atlantic, this half-starved shivering specimen was warmed and fattened on board; his health restored, and his safety ensured; this Italian was transported to the fair land of England; really safe at last, he was accommodated in some pleasant camp: it was here he discovered the loss of his cigarette lighter. Thus Britannia Rules the Waves.