- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2024 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By James (JO) Morrice

It is with great sadness that we hear of the recent passing of our friend and comrade Captain JO Morrice RAN and trust this short article helps serve as a small but fitting tribute to this fine officer and gentleman.

In 1952 I had the privilege of serving in the cadet training ship HMS Devonshire when the then King of Norway, King Haakon VII, paid a visit to the ship in Oslo. I also had the honour of being selected as a member of the Royal Guard paraded for this historic occasion. At the time Devonshire was undertaking its Summer Cruise visiting ports in England, Scotland and Norway. Embarked were 132 cadets from Commonwealth Navies, twenty of whom were members of the 1948 Jervis Year entry to the Royal Australian Naval College. King Haakon was no stranger to the Devonshire. In the early years of WWII, when the Germans were rapidly overrunning France, the Allied High Command decided to withdraw forces from northern Norway. At the same time the Luftwaffe were attempting to wipe out Norway’s unyielding king and government. Thus in June 1940 it was decided to evacuate the royal family and Norwegian government officials from Tromsø, where a provisional capital had been established. Several days earlier the First Cruiser Squadron, of which Devonshire was flagship, had been attacked by bombers while searching for German ships in waters to the west of Norway. Fortunately, Devonshire was undamaged and therefore able to undertake the evacuation.

With 461 passengers on board, Devonshire made a speedy and safe passage to Great Britain where King Haakon and his Cabinet set up a Norwegian government in exile. Yet the evacuation had been extremely costly for the Royal Navy. The aircraft carrier HMS Glorious and her escorting destroyers HM Ships Acosta and Ardent, operating some 50 miles from Devonshire, were sunk by the German pocket battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau with a loss of life of 1519 men. Devonshire was the only British ship to receive the sighting report of the German ships but could not disclose her position by breaking radio silence.

During a long period in exile, King Haakon attended weekly Cabinet meetings. His speeches were regularly broadcast to Norway by the BBC, and despite Hitler’s attempts to depose him, he became an important national symbol to the Norwegian resistance. Such resistance was widespread and many Norwegians wore surreptitious symbols of solidarity with their exiled King and government. Following the capitulation of German forces in Europe in May 1945, King Haakon made a jubilant return to Norway in HMS Norfolk, escorted by other ships of the First Cruiser Squadron including Devonshire.

His arrival in Oslo marked the fifth anniversary of his evacuation from Tromsø. Seven years later, King Haakon had the opportunity to visit his ‘old ship’. By this time Devonshire bore a plaque commemorating the historic wartime evacuation. What follows are extracts from an article in the 1952 Summer Cruise edition of The Devonshire Magazine. It is most probable that the article was written by an unnamed cadet.

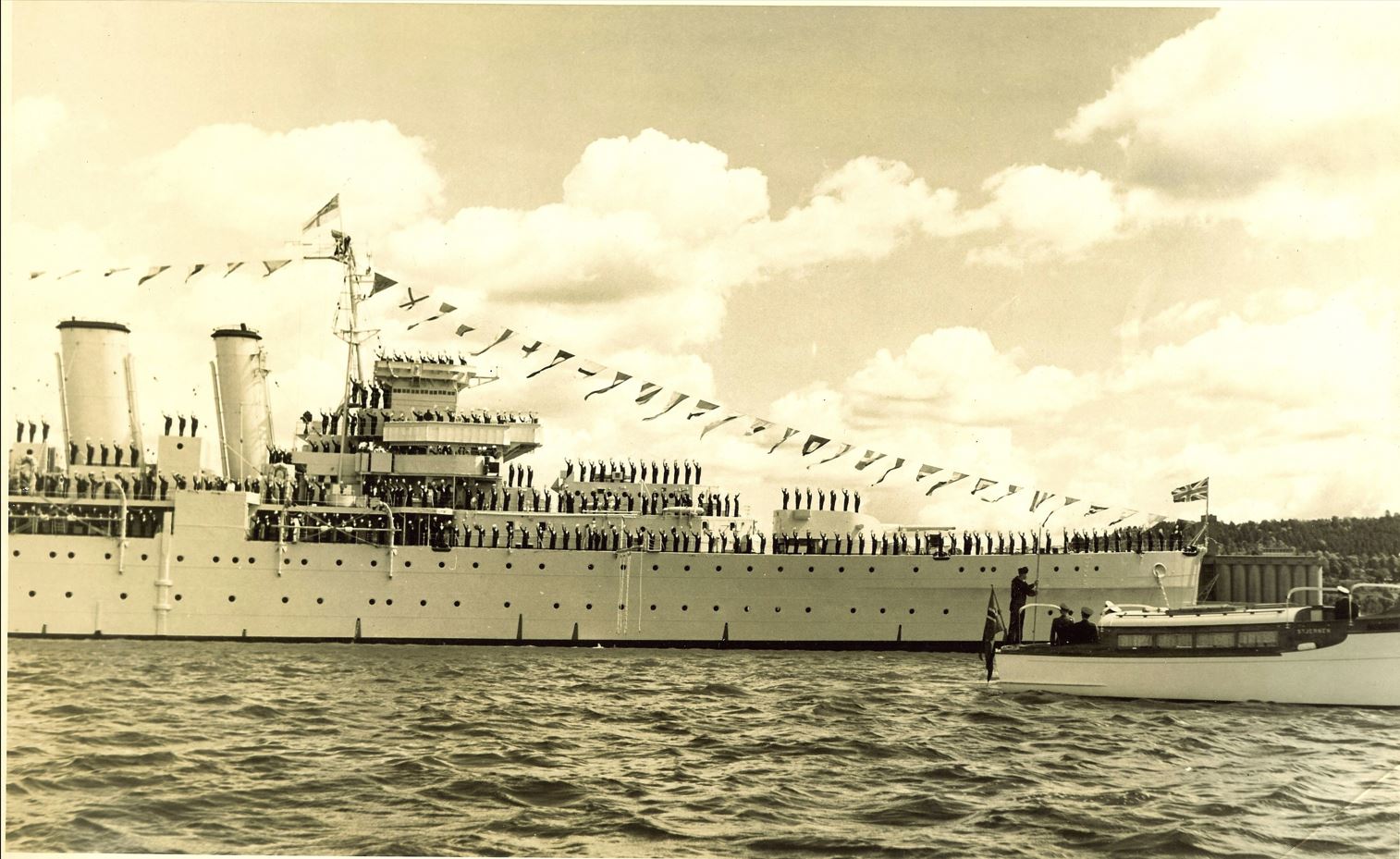

Before Colours, time was spent in rehearsing the ‘Man and Cheer Ship’ drill. This was repeated until even the Commander was satisfied and until even the meanest intellect on board understood that ‘Hurrah’ and not ‘Hurray’ was the operative word. At Colours, the ship was dressed overall; the stage was set! At 1053 punctually, His Majesty, accompanied by Crown Prince Olav, arrived at the jetty at Honnorbryggen where he was received by a Guard drawn up in the best Royal Marine style … As the Royal Barge left the jetty the guns of the ancient Akershus Fortress fired a salute of 21 guns – the Sovereign was afloat! Devonshire replied to this salute and, although only 2 lb blank charges were used, those of us in the immediate vicinity wished that we had not forgotten the cotton wool. At 1100, the Royal Barge was alongside Devonshire; as His Majesty, dressed as an Admiral of the Royal Navy (he is an honorary Admiral), stepped over the side, the Norwegian Royal Standard broke at the Main and the Admiral’s Flag at the Fore, and as the Cadet Royal Guard came to the present, the band struck up the Norwegian National Anthem … At 1145, the Royal Party left the ship. As the Royal Barge drew away, the Royal Standard and Admiral’s Flag came fluttering down and Devonshire fired a 21-gun salute. Then we manned ship and although we could not see it ourselves, we must have presented quite an impressive sight. Our cheers, too, we were told, sounded right lustily and carried a long way. We also remembered to say ‘Hurrah’! Then the Royal Barge, again with its motor-boat escort, headed for shore and, as the King neared the jetty, once again Akershus Fortress greeted its Sovereign with a Royal Salute.

Truly a memorable occasion for us – one worthy of the ‘Make and Mend’ which followed.

In 1955, three years after he had revisited Devonshire, King Haakon VII fell and fractured his thighbone, confining him to a wheelchair. He died in 1957 at the age of eighty-five, having served as monarch for nearly 52 years. He is regarded as one of the greatest Norwegian leaders of the 20th century. Yet this man of considerable integrity, and who was held in high esteem, was not Norwegian by birth. In fact, he was born Prince Carl of the Schleswig Holstein-Sondberg-Glucksburg branch of the House of Oldberg which had been the Danish royal family since 1448. But that is another story.

Having seen extensive action in WWII, the County class heavy cruiser Devonshire began a new phase of life in 1947 when she was converted into a cadet training ship. Three training cruises were conducted annually to the West Indies (Spring), UK and Norway (Summer) and the Mediterranean (Autumn). Her complement included officer cadets under training from New Zealand, Australia, Ceylon, India, Pakistan, Canada, Northern Ireland and Great Britain. It was a truly diverse group of cadets yet a generally cohesive one from which many lifelong friendships were made. For the cadets concerned, the early sea training was invaluable. For 17/18-year-old Cadet Midshipmen from the Antipodes, it was an eye-opener to a new world.

The good ship Devonshire served in the cadet training role until 1954 when, like many other men-of-war, her distinguished career came to an inglorious end in a scrap metal yard. For the next two years, sea training of cadets was conducted by the Colossus class light aircraft carrier HMS Triumph, her last training cruise being in the autumn of 1955 when significant changes were made to the system of training Royal Navy officers. For the RAN and navies of other Commonwealth countries, an era of common training with the Royal Navy had come to an abrupt end. The decommissioning of the Devonshire and the death of King Haakon are now timelines in history, as is the historic link between Great Britain and Norway. It was a link forged by the Royal Navy, not only by evacuating King Haakon and his government to the United Kingdom in Norway’s hour of need, but also enabling the King’s triumphant return to Norway at the end of the Second World War.