- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, History - Between the wars, Royal Navy

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2024 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Graeme Lunn

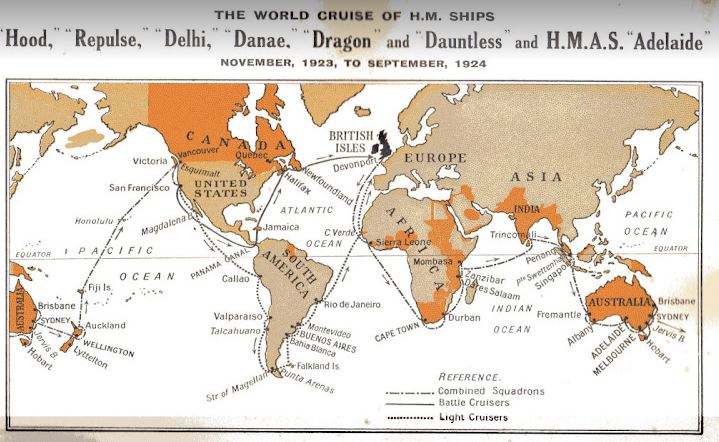

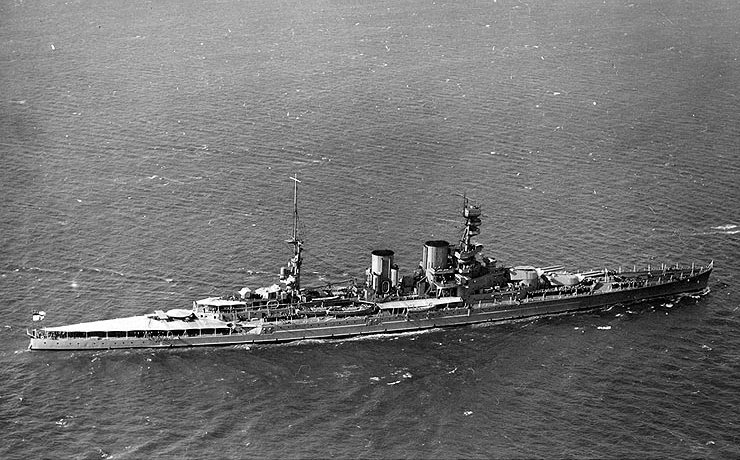

John Brown and Company laid down the keel for a battlecruiser in September 1916 that would become the Royal Navy’s epitome of firepower, speed and grace during the inter-war decades. Engineer Commander Ernest Sydenham, standing-by the August 1918 launch and fitting out of HMS Hood, was her inaugural Commander (E) on commissioning in May 1920. Hood’s dimensions, even one hundred years later, are still impressive. Each of Hood’s main turrets, as well as her armoured conning tower, weighed 900 tons. If Hood was sat on the seabed in the deepest part of the English Channel, between Dover and Calais, her top twenty-four metres would still be above the waves.

On February 21st 1924, every newspaper in Australia was excitedly announcing that the first wireless signals had been received from Hood in the Indian Ocean, over 3000 miles distant from the Navy transmitters near Melbourne. The reply message read: ‘At this first moment of contact the Commonwealth Government extends a cordial welcome’, a welcome which would approach a frenzy. Also in Melbourne was the now Engineer Captain Sydenham, loaned as the RAN’sDirector of Engineering since the previous May. But why was Hood approaching the shores of Western Australia two and a half years after her commissioning?

Hood was Flagship of the Special Service Squadron on its Empire Cruise, a circumnavigation that was said to be the greatest voyage embarked on by the Royal Navy since that of Commodore Anson in 1740. This Empire Cruise, by Hoodand her six consorts, was costing £600,000 at a time of severe budget restrictions. The British Government and the Royal Navy had quickly learned that if they wanted to impress, Hood was the vessel. The battlecruiser always proved a drawcard sensation; the largest warship in the world, she awed wherever she sailed and the British wanted to awe the Dominion.

Australians were used to seeing their own 22,000 ton battlecruiser HMAS Australia as the largest vessel, warship or merchant normally in port. The country had recently been visited by the 33,000-ton HMS Renown, nicknamed the ‘Refit’. She had come out in 1920 with the Prince of Wales onboard, but the focus then had been on Prince not vessel. In yet another refit some aft guns had even been removed, to give her a royal promenade deck, along with a squash court and cinema between the funnels. In contrast, the undiluted power embodied within Hood’s 47,000-tons and graceful proportions meant that people literally mobbed her wherever she appeared. Not for Hood a humorous nickname bestowed by the lower deck – Curacoa was the ‘Cocoa Boat’, Royal Sovereign the ‘Tiddly Quid’, Hotspur was, inevitably, ‘Tottenham’ – she was simply the ‘Mighty Hood’, and so she remained throughout her life.

Britain was suffering post-war years of hardship, unemployment and heavy taxation. Within the navy it was the era of the Geddes axe. Sir Eric Geddes had served as First Lord of the Admiralty from 1917 to 1919 where, although a businessman and then a civilian Lord of the Admiralty, he granted himself the rank and uniform of a Vice-Admiral. In the early 1920s his Committee of National Expenditure slashed defence expenditure. The £190M spent in 1921-1922 was reduced by forty percent the following year, with many officers and men finding that their services were no longer required. Steaming time was heavily curtailed, and everywhere in the navy economy ruled. No economies, however, seemed to apply to Hood when she commenced her years of service.

Flagship of the Battlecruiser Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet, Hood was the newest pride of the Royal Navy. Costing over £6M to build, the Admiralty wanted, indeed needed, to show her off and justify her existence. On commissioning and initial work-up thought had been given to Hood reinforcing the British Baltic Squadron against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. Instead, she had departed on a Scandinavian cruise to show the flag rather than the gun. By completion of that cruise she had welcomed aboard every king, queen and crown prince of those three countries.

Along with the normal annual round of combined fleet and squadron exercises, single ship evolutions, sports regattas, dockings and minor refits the next few years saw additional goodwill visits. In 1921 King Alfonso of Spain was welcomed aboard. It was an unsettled year, causing Hood to land three seaman and marine battalions to render assistance in Fife during the April strikes. King George V visited in 1922, and shortly afterwards the gunnery department had the pleasure of their target vessel being the interned German light cruiser SMS Nürnburg. Later in 1922 Hood sailed to South America, helping celebrate the centenary of Brazil’s independence.

Of most consequence to the world’s navies at this time was the Washington Naval Conference, called in response to the accelerating arms race in capital ship building. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, established in 1902, expired in 1922 under pressure from Canada and the United States who saw Japanese aggression as only a matter of time and opportunity. The decades long prejudices of Australians fearing the ‘Yellow Peril’ to the north had only been briefly diverted by the German belligerence of World War One. This perceived oriental threat had been one of the emotive initiators of Federation, the joining together of the six Australian colonies in 1901. It was the heyday of the White Australia Policy in immigration and even that was selective; British yes, Irish and other northern Europeans if you must, but it certainly did not extend south to Italy or Greece. The central issue for Australian diplomacy and defence was security in the Pacific and the looming menace that Japan posed to that security. Twelve thousand miles from the mother country, Australians felt uniquely vulnerable.

In the early 1920s there was a profound desire for peace through international arbitration and disarmament. The League of Nations was the leading hope for this movement and it had established the Permanent Court for International Justice. Disarmament for Australia was a committed government principle under Prime Minister Stanley Bruce. Having been severely wounded winning the Military Cross with the Royal Fusiliers at Gallipoli in 1915, he had personally urged disarmament before the League of Nations at Geneva in 1921.

The 1922 Washington Conference led to the Washington Naval Treaty with its strict limits on the signatory states’ naval forces The treaty followed the dictum to: ‘disarm some of what you have and limit what can be built’. Total tonnage was limited as were individual ship sizes. There were disarmament and scuttling requirements for many existing warships to satisfy total tonnage limits. Australia was counted within the Royal Navy limits and placed in reserve for eventual sinking. It was a bitter pill for the Dominion as this expensive vessel had been recommended by the Royal Navy for the new Royal Australian Navy. Constructed in John Brown’s shipyard, she had steamed into Sydney Harbour in 1913, less than a decade before.

A size limit of 36,000-tons was set by the Washington Naval Treaty for all battleship and battlecruiser construction. This meant that in the RN the N3-class battleship and G3-class battlecruiser designs – the latter to be 54,000-tons with 16” main armament – were cancelled. The USN cancelled their 48,000-ton South Dakota-class battleships, battleships specifically designed to be larger, better armed and with more armour than Hood‘s Admiral-class. The Japanese cancelled their Kii-class, and also their 47,000-ton No.13-class with a proposed 18” main armament. The result for Hood was that she remained the world’s pre-eminent warship for the following two decades.

Many hulls already on the slipways, if not cancelled and broken up, were converted to aircraft carriers, their construction and individual tonnage not being as strictly curtailed in the Treaty as battleships and battlecruisers were. The US Lexington-class battlecruiser plans were drawn after the British naval constructor, Stanley Goodall, visited Washington with battle damage reports from Jutland and detailed construction drawings for Hood. The proposed Lexington class could have been mistaken as twin for the British Admiralty class, but by 1928 USS Lexington, and her sister ship USS Saratoga, had been converted on slips into the largest aircraft carriers of the era. They were fast fleet carriers of 44,000-tons, able to make 33 knots and carry eighty aircraft. Perversely, while the disarmament clauses of the Washington Naval Treaty did not succeed in preventing future conflict, by inadvertently favouring carrier conversions the Treaty shaped the next war’s strategy and conduct.

To understand why Hood came to Australia in 1924 we need to consider several remarkable men. The first is Sir Maurice Hankey, one of the most powerful men within the British ruling establishment during the first half of the twentieth century. He was Secretary to the Imperial War Cabinet, and then Secretary to the Cabinet for twenty-two years. Hankey was also Clerk of the Privy Council, in which role he served as Secretary-General to many Imperial Conferences. For twenty-six years from 1912 he was concurrently Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence.

The Committee for Imperial Defence was a fascinating administrative product of Empire. The military and naval opinion of the various Chiefs of Staff merged with the political will of the government in this committee. While it had no executive power its Secretary, Hankey, made direct recommendations to Cabinet where its Secretary, Hankey, approved the recommendations being sent out to the Dominions, where they held great influence. In 1923 the committee turned their attention to Australian naval policy.

Early that year a secret memorandum titled ‘Empire Naval Policy and Co-Operation’ was sent to the Naval Board in Australia, and strongly urged for adoption at November’s Imperial Conference. The Admiralty under its First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty, recommended continuing the separate Dominion navies operating modern cruisers with interchange of ships, officers and men with the RN. The systems of training and promotion, as well as the bases at which the ships would be maintained, refitted and supplied were to be as similar as possible. Wireless telegraphy was to be improved but, above all, the matter of first importance was provision of strategic fuel reserves. The memorandum stated that ‘oil fuel has come to stay as a propellant for vessels of war’. Oil was being adopted, not because it was cleaner than coal, but because it gave a considerably longer range for the same bunker capacity.

Of the ‘big’ Dominions, Australia had the most advanced naval forces and proved the most receptive to Admiralty wishes. The proposed naval policy included developing Singapore as a main fleet base, while Australia constructed and then maintained efficient mobile light forces. It was baldly stated that ‘under existing conditions Japan must certainly be considered as the naval power with whom the Empire is most likely to be drawn into conflict’. The strategy envisaged was for the RAN’s cruisers to protect Australia’s coast and trade routes while diverting, delaying and harassing the Japanese until the arrival of the Royal Navy’s Main Fleet into the Asia-Pacific theatre to operate from that, yet to be constructed, Singapore fleet base.

This policy and strategy, mooted by Hankey, had the strong backing of the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Honourable Leo Amery. A correspondent in the Boer War who had nearly been captured with Winston Churchill, Amery had helped draft the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and, with Churchill, later opposed appeasement in the 1930s. It was his voice in Parliament’s 1940 Norway Debate who quoted Oliver Cromwell at Chamberlain – ‘You have sat here too long… in the name of God go!’

Both Amery and Hankey championed the Empire. Both wished to strengthen the ties between Britain and the self-governing dominions but recognised a conundrum, that of maintaining adequate defence of territory and trade while, in Hankey’s words: ‘the urgent desire for disarmament held sway’. Not all was altruistic, the United Kingdom was spending £12 per head annually on defence while Australia was spending £6. A little levelling of the fiscal scales was desired.

First Naval Member of the Commonwealth Naval Board was Vice-Admiral Sir Allan Everett KCMG KCVO CB. On April 24th, 1923, he sent a confidential minute to Prime Minister Bruce about the ‘possible expansion of the RAN which may result from the Imperial Conference’, active seagoing forces then being three light cruisers and a small destroyer flotilla. Bruce was presiding over a prosperous country; Commonwealth income was £4 million above estimate for the financial year and there was an accumulated surplus of £10 million. The population was approaching six million, helped by both a high birth rate and immigration. Bruce’s electoral platform had been ‘Men, Money and Markets’ making him naturally inclined to consider the need to protect sea-borne trade. The Prime Minister, anticipating that he would tilt Australian defence policy heavily in the Navy’s favour, decided he would personally vet the next loan admiral proposed to head the Royal Australian Navy and who would supervise any expansion.

That same day, April 24th, the First Lord wrote a note to the First Sea Lord saying he wanted to send a modern squadron under Hood to the Empire immediately after the Imperial Conference. Its purpose: ‘to follow up the Agreements for Cooperation made at the Imperial Conference by creating Dominion interest and enthusiasm’. The proposal was for gun-boat diplomacy of the non-belligerent variety, encouraging greater Dominion participation in naval affairs by parading the world’s largest warship and entourage.

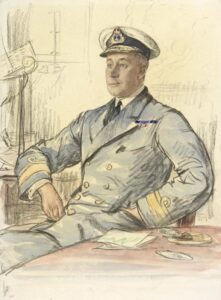

As naval bureaucracy geared up to carry out the First Lord’s wishes, Rear-Admiral Sir Frederick Field KCB raised his flag in Hood on May 15th, 1923. During the war Field had been Flag Captain of HMS King George V at Jutland and then Chief of Staff, First Battleship Squadron. Selected specifically to command during the anticipated world cruise, he had been confidentially reported as having a ‘charm of manner that endears him to all while earning the respect and confidence of every Captain in the Squadron’. Joining on the same day was his Flag Captain, John Im Thurn, a wireless telegraphy specialist who had recently run the Admiralty’s Signals Division.

Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, with his Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon, hosted the Imperial Conference from October 1st to November 8th 1923. Interestingly it was at this conference that the three-mile limit for territorial waters, traditionally the range of a heavy cannon ball, was extended out to the twelve-mile limit. After Baldwin’s opening statements the First Lord of the Admiralty’s speech reiterated the memoranda of the Committee of Imperial Defence. He also strongly stressed the value of a Singapore Naval Base. Agreeing to the principle that each portion of the Empire should provide for its own defence, the Australian Prime Minister promised to lay before his government the Admiralty proposals, namely the replacement of obsolete cruisers, establishing oil reserves, considering an advanced naval base in northern Australia and the modernisation of wireless stations to fulfil naval requirements. With this, Amery officially announced that he was sending a squadron on an Empire Cruise, and Bruce assured a hearty welcome in Australia for that squadron.

Bruce immediately made sure the Australian press was aware of the main points covered at the Imperial Conference; in modern terms, he ‘briefed the media’. At the same time the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Devonshire, began sending briefing information to the Governor-General of Australia, Lord Forster, to coordinate the proposed visit.

While committees and clerks were exercising the administrative sinews of Empire, Hood had been on another short Scandinavian cruise with Repulse, followed by an October docking. On November 5th, Sir Frederick Field’s title changed from Rear-Admiral Commanding Battlecruiser Squadron to Acting Vice-Admiral commanding the Special Service Squadron. His squadron consisted of the Battlecruiser Squadron and Rear-Admiral Sir Hubert Brand’s First Light Cruiser Squadron with HMS Delhi as the flagship. These D-class cruisers were the most modern and powerful cruisers at the time, their 6000-tons able to achieve a respectable 29 knots. The Admiral’s staff embarked in the flagship except for the Squadron Engineering Officer, Captain Mark Rundle DSO, who stayed in Repulse for the whole cruise. Perhaps Repulse’s nickname, the ‘Repair’, a clever take on her Latin motto ‘Qui tangit frangitur’ (Who Touches me is Broken), had proved a well-earned one.

The Colonial Secretary in Whitehall, fully aware of the importance of this cruise and the hopes riding on its success, informed the Australian Governor-General as the Squadron sailed that he was attaching to the Admiral’s staff his Acting Assistant Secretary, Harry Fagg Batterbee, who was appointed Political Secretary for the cruise.

On November 27th 1923 the ships weighed anchor in Devonport and Spithead to ‘meet our kinsmen overseas, to carry them a message of peace and goodwill, and to revive in their hearts and in ours the ties that bind them to us and us to them.’ Although months away from Australia, local newspapers started publishing the dates of the visit, the names of the ships and their respective captains. Showing mounting excitement, they followed the progress of the squadron towards Australia. The vice-regal offices in the nation’s capitals began work to coordinate the official functions and entertainments with Melbourne’s Navy Office, State and Federal Governments, town halls and local organisations.

Considerable coordination was required since Australia was an Imperial Dominion of six states. Each state had a Governor, appointed by the Crown, living in a palatial Government House, and there were state legislatures with upper and lower houses led by a Premier. Overall was the Governor-General and a Federal Government in Melbourne, since Canberra was still being slowly hacked out of the bush. The Governor-General and his Governors were all British, retired Knights of the Realm or professional colonial administrators. For example, the Governor of Queensland Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Mathew Nathan GCMG, after service as a soldier went on to be Governor of Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, Hong Kong and Natal.

In January 1924 the Naval Board granted a special entertainment allowance to the wardrooms of the Australian fleet to allow them to provide adequate fraternal hospitality during the visit. The Treasury thought £35 for each light cruiser and destroyer adequate but the Admiral, recognising the reality of naval drinking, managed to triple that.

On February 17th 1924, the Special Service Squadron, often referring to themselves now as being on the Booze Cruise rather than the Empire Cruise, departed Singapore. There only 29,000 people had visited the ships, even though the Commander-in-Chief China Station had sailed down with four of his own command. Ahead lay 2300 nautical miles steaming to reach Fremantle, the port city for Perth, capital of Western Australia and still one of the most remote cities in the world.

Days at sea are never idle in a warship. During the passage there were transmitting station endurance tests, smoke screen trials, dropping of depth charges, officer of the watch manoeuvres, sub-calibration throw-off firings and high-angle firings in addition to regular fitness training on the quarterdecks and boat decks for the squadron’s sports teams. Overall, there was the ever continuous round of polishing and painting since Hood and her squadron would represent their service like few before or after. During the practice torpedo firing there was the anxious time of searching and recovery. When the worried looking Paymaster Commander was asked what he was looking for through his binoculars he replied ‘I am looking for £1500’, a sum then that would have purchased three houses. Divine Service was held on Sundays and there was the daily ‘up spirits’.

A Japanese Training Squadron, of three old cruisers and 2500 men, had visited Australian ports in January to a subdued reception. The previous month the Resident Commissioner in the Solomon Islands had reported to the Secretary of Colonial Affairs, Lord Devonshire, about suspicious Japanese vessels, information promptly despatched to the Governor-General Lord Forster. In contrast, the welcome to be bestowed on Hood and the Special Service Squadron exceeded in scope, numbers and enthusiasm even that accorded the arrival of the newly constructed Royal Australian Navy in 1913. It proved greater than any other foreign squadron had ever experienced, including the sixteen American ships of the Great White Fleet in 1908.

Considered and careful planning for the Special Service Squadron ensured a comprehensive visit to help realise the First Lord’s aims. As a federated nation, where each state had equal voting power in the Senate whatever their population, it was important that no state missed out on seeing and experiencing the security provided by the Royal Navy. Every capital city, and as many secondary ports as possible, were to be visited. When not able to visit, the ships were to stand in as close to shore as was safe so as to be visible to the local residents.

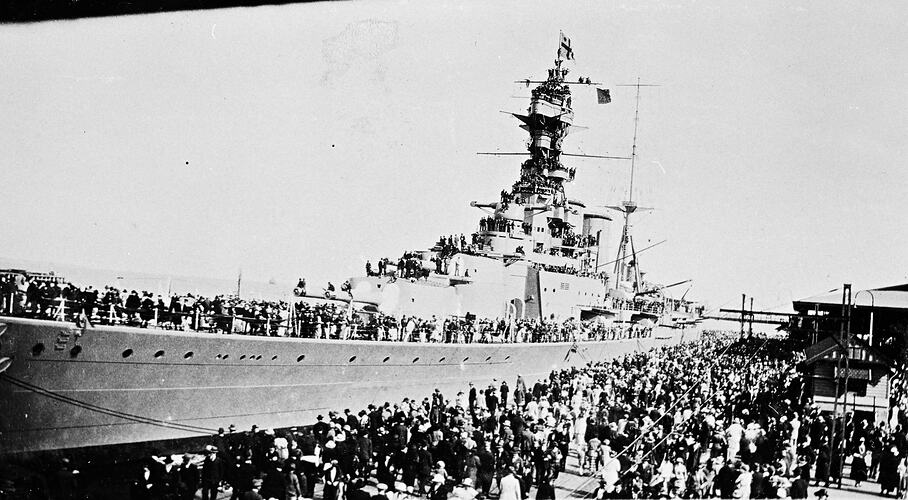

After 15,000 nautical miles the Squadron arrived in Fremantle on February 27th 1924, the ninety-third day of their cruise. Western Australia, twelve times larger than the United Kingdom, elicited the observation that: ‘of such spaces and of such men is the Empire composed’. Prime Minister Bruce’s welcome message was floridly exuberant: ‘To Australia as to Britain the Navy means everything. Without the dominant British Navy we would be utterly destroyed’. The Fremantle Harbour Authority, proud that they could berth even Hood, had built new brows to reach her as theirs were too small. Those brows were purchased for £100 by the Navy Board and carried by the battlecruisers for use when they got to Melbourne.

The programme of social and sporting events and lavish hospitality in the capitals of Perth, Adelaide, Melbourne, Hobart, Brisbane and Sydney would be repetitive, but an example is enough to give an idea of the overwhelming nature of the welcome provided.

The Squadron itself remarked that we ‘… seemed to overawe them as the first time in their lives anything so great as these ships had been in their harbour’. After a 15-gun salute the Admirals disembarked to inspect the Guard of Honour and make their official calls on the Governor, Sir Francis Newdigate Newdegate GCMG GCStJ, the State Premier and the Mayor of Perth. Adding to the official welcome by members of the state government, the Acting Prime Minister (Bruce was still at sea returning from Europe) and the Minister of Defence travelled 2000 miles by train to personally give theirfederal welcome to the Squadron on its first

Australian landfall. One of the high points planned in each capital was the Ceremonial March by the Naval Brigade. Here they had good practice as, after the 1500 sailors and marines with two field guns had marched through Fremantle, they entrained for the twelve-mile journey to Perth and repeated the exercise.

There was heartfelt appreciation at this demonstration of the protection the Royal Navy afforded their state’s remote settlements, but the most immediate issue was emigration and settling the land. Not missing an opportunity Western Australia’s Premier, Sir James Mitchell KCMG, stated: ‘We want many of your sailors to come out here and live’. Even in this, the most sparsely populated state, 100,000 visited the ships and on sailing, Hood had acquired a kangaroo named Joey as ships mascot.

On their way for a brief visit to Albany the squadron sailed within two and a half miles of Bunbury, allowing the thousands who travelled to the coast from country farms and settlements to see the squadron pass.

Reaching Adelaide on March 10th there was severe disappointment that the battlecruisers had to anchor off. Hood’s captain rightly felt that one foot (thirty centimetres) of clearance under his ship was not sufficient, especially when every degree of heel required an extra foot of clearance. The Vice-Admiral explained in homely terms to the people of Adelaide that he ‘could not put a quart into a pint pot’. It did not dim the enthusiastic welcome with the largest banner reading ‘South Australia Welcomes the Sons of the Sea’.

Field stayed ashore at Government House as a guest of the Governor, Lt General Sir Tom Bridges KCB KCMG DSO. Even with Hood and Repulse at anchor there were still 70,000 visitors to the ships’ open days. The Premier, Sir Henry Barwell KCMG, declared that: ‘The mere fact that these ships of war – real fighting ships of first class efficiency – are even now within South Australian waters will be causing a thrill of satisfaction throughout the State. The Squadron must inspire us all with a keen sense of national pride and security. The Navy … the binding force that holds together the edifice of Empire.’ The First Lord of the Admiralty’s plan to create Dominion naval enthusiasm was succeeding beyond measure.

Melbourne was planned to be a highlight of the Squadron’s time in Australia. Federal as well as State capital, the official entertainments doubled. Making it clear that they were one of the most prosperous cities in the Empire, Melbourne incorporated Hood and her squadron into Fleet Week. The Commonwealth Immigration Office placed 30,000 free picture postcards on the ships. Along with immigration literature a souvenir book was presented to every man. An internal office memo observed: ‘I am informed that in a very short time the service of many of these men will be expiring so it is a favourable time for publicity for Australia’. No postcards are recorded as having been handed out to the recently departed Japanese sailors.

The public were impressed when Hood undertook her own pilotage through the challenging entrance called the Rip into the expansive Port Phillip Bay on March 17th. Port Phillip, 750 square miles (1940 square kilometres), is six times larger than Scapa Flow but relatively shallow. The Couta boats of the local fishing fleet watched Hood make her first vital starboard turn through the Rip. In the forty-two mile passage up to the piers of Port Melbourne hundreds of small craft, plus larger steamers carrying numbers of members of the Commonwealth and State governments, accompanied the warships. Every pier, wharf and vantage point was packed with tens of thousands of people, while biplanes of the RAAF flew overhead. Stepping ashore, the Vice-Admiral was literally mobbed by enthusiastic crowds when making his official calls on the Governor-General of Australia Lord Forster, the Governor of Victoria the Earl of Stradbroke, the Prime Minister (newly returned from Europe), the State’s Premier and of course the Lord Mayor.

Field wrote: ‘Warm as our welcome had been in all the places previously visited, it was altogether surpassed by the reception accorded to us by the citizens of Melbourne, which can only be described as amazing’. That night the Governor-General gave a dinner for the senior officers while Lady Stradbroke hosted 250 Petty Officers and men at the Tivoli Theatre, and the newspapers reported a gay scene at St Kilda as the officers came ashore. The next day the Naval Brigade marched past the saluting base at Federal Government House. At this time the RAN could normally only muster 500 men for a review march, making it an impressive sight to see the squadron’s 1500 sailors and marines passing. The city was overrun and the trams and railways overwhelmed.

Having read the guides published in all the papers 80,000 people visited the ships after the march and tens of thousands more had to be turned away. Visitors to the ships were everywhere, even swarming to the heights of the range finder above the conning top.

Modern health and safety inspectors would have been appalled, and it is a wonder that no injuries occurred. Public transport, theatres and cinemas were free to men in uniform. Since the guidebooks had also informed Victorians of the sailors’ rates of pay they knew that the free entertainment would have been especially welcome. Official entertainments and tours up-country were also free to the hundreds who could be released daily from duty. During the squadron’s visit 490,000 people visited the ships, out of a city population of 900,000, while those who could not get onboard spectated from ashore. Australia’s greatest artist, Sir Arthur Streeton, painted a cityscape of Melbourne with Hood looming in the distance.

The Prime Minister boasted that: ‘Our forefathers came from Britain and 98% of our people are of pure British descent. We share its glorious traditions: we are, in fact, the most British nation in the world!’ At every public and private opportunity Vice-Admiral Field advocated agreement with the naval strategy for Australia, decided by the Admiralty and the Committee for Imperial Defence as enumerated at the Imperial Conference, with an openness that would have made most naval officers nervous. Personally received by the King and the First Sea Lord before departing on this cruise, it was apparent Field had been given the latitude to speak in Australia what would normally be well out of a serving officer’s remit, however senior. Afterwards Field commented that: ‘in expressing the views of HM government in regard to the share that the Dominion should take in the naval defence of Empire he was received with sympathy and consideration not only by the responsible ministers but by the whole community’.

‘Behaves like a gentleman’

The media were approving of the squadron sailors ashore reporting that ‘their conduct has won the unstinted admiration of all classes’, and the Police Commissioner was quoted saying ‘the British sailor ashore behaves like a gentleman and Melbourne has something to learn from him’. Pleasing words, but probably no-one had told the Commissioner that Hood‘s Executive Officer and all the other ship Commanders had landed all known troublemakers in late November, just before sailing.

Melbourne was the home of Navy Office and the Commonwealth Naval Board where the head of the Royal Australian Navy presided. Newly arrived Rear-Admiral Percival Hall-Thompson CB CMG, fresh from his command of HMS Royal Oak, and personally approved by the Australian Prime Minister, had attended the Imperial Conference at the Australian Delegation’s table. Fully briefed on what the Admiralty wanted of Australia, and hearing Bruce’s commitment at that conference, he knew what was expected of his loan service tenure. He was to upgrade all the RAN’s specialist schools, dockyard support and supply infrastructure to ensure the efficient operation of any new warships. That secret CID memorandum had stated: ‘new ships are of little use without trained manpower and that training takes longer than the building’, the contemporary view being that it took three years to build and commission a warship, but at least nine years to train a sufficient depth of skilled ratings to efficiently man and fight that ship. Hall-Thompson prophetically decided that it was also time to encourage some RAN officers to learn Japanese.

Contrast in numbers

At the meeting of the Council of Defence on March 21st 1924, the Prime Minister reported on the resolutions of the Imperial Conference. Consider that while the Prime Minister was talking, several miles away lay the most modern Royal Navy squadron, manned by 4600 officers and ratings when the entire Royal Australian Navy could only muster 4013 officers, men and boys. At the centre of that squadron was the world’s greatest warship, whose construction costs had been three times the annual Australian naval estimates of £2.2 million. Hood was visible evidence across the rooftops that the proposed strategy, of a main fleet sailing to Singapore in time to protect the Dominion from a bellicose Japan, was viable. Additionally, this squadron was led by a British Admiral whose speeches advocating a new Australian defence policy had met popular acclaim and enthusiasm at every official engagement.

Whatever the generals might have thought about a naval-centric reliance for national defence it had become, almost by fait accompli, a national commitment. Already agreed to by the Prime Minister in London, the policy was being swept to a popular accord within the nation because of the presence of the Special Service Squadron led by the ‘Mighty Hood’. It was a commitment that would see the annual naval estimates double within three years as Engineer Captain Sydenham initiated tenders for the construction program integral to the new five-year defence plan. In a speech delivered on March 25th, Bruce told his parliamentary supporters that he intended to purchase two new cruisers to commence the replacement of the obsolescent Australian fleet.

During the visit to Hobart from March 27th to April 3rd many of the planned activities were cancelled because of inclement weather, but the enthusiasm in this small state of 213,000 people was just as pronounced. Although there was lingering embarrassment at its convict heritage, which had caused a name change from Van Diemen’s Land to Tasmania, its people were as generous in their welcome as the larger states had been. Parties from the squadron travelled throughout the state, giving speeches at five townships to people who could not make it down to the capital. At a wharf adjacent to Hood was the new RMS Maloja, at 22,000-tons the largest liner on the Australia run in those years, allowing visitors a scale with which to better appreciate the battlecruiser’s size at a time when merchantmen rarely exceeded 10,000-tons.

‘Osborne of Australia’

Heading north past Twofold Bay on April 4th no landing was possible due to the sea state, but the ships stood in so that the large crowds on the cliffs were able to admire them. Three days were spent anchored in Jervis Bay, for maintenance and much-needed recuperation from the social excess for the crews. The site of the Royal Australian Naval College, slowly producing the future officer core of the Royal Australian Navy, was generously called the ‘Osborne of Australia’ by the visiting officers despite the small number of cadets. There was certainly the local determination to continue those traditions which had nurtured the Royal Navy, but the College was organised on a democratic basis where parents paid nothing of the £2000 cost per annum per cadet, and that year’s entry had only numbered fourteen cadet midshipman aged thirteen.

Regularly, throughout the visit, the private secretaries in the Governor-General’s office had compiled every newspaper article about the squadron at each port they visited. Every laudatory speech given by officer or civilian, visitor or local, at any function private or official was reported on, and then despatched back to the Secretary for Colonial Affairs for dissemination around Whitehall. The Governor-General observed: ‘In every state the welcome accorded was of an enthusiastic character by the governments and by public bodies and private citizens’. At the Admiralty, they noted on April 7th 1924, that Australia now fully concurred with their Empire Naval Policy.

The final port visit for Hood was Sydney from April 9th to April 20th. One of the great harbours of the world, it had been home port of the Royal Navy’s Australia Station from 1859 to 1913. Latterly a Vice-Admiral’s command, at its greatest extent the station encompassed a quarter of the Southern Hemisphere. Sydney was now home port to the ships of the Royal Australian Navy commanded by another Admiral on loan, Rear-Admiral Albert Addison CMG. It had also been the home of Rear-Admiral Brand’s father, Viscount Hampden, when he had been Governor from 1895 to 1899. Both Hall-Thompson and Sydenham had served on the Australia Station, Hall-Thompson additional to HMAS Katoomba as Inspector of Warlike Stores from 1901 to 1903, and Sydenham additional to Powerful as the Royal Navy’s Coal Inspector for mines in Australia and New Zealand from 1909 to 1913.

Half a million people gathered on the heights and shores to see the Squadron arrive and Vice-Admiral Field had to revise his Melbourne observations to proclaim this was the greatest moment of the cruise. In his words there was a ‘sense of animation and enthusiasm ashore and afloat’. Partly that was because Melbourne had so thoroughly enjoyed Fleet Week that the Prime Minister and his principal Federal Ministers, the military chiefs, society and many, many women followed the Squadron to New South Wales to continue the official festivities and the partying.

Ten day programme

Taking the salute from the squadron’s naval brigade was the Governor of New South Wales, Admiral Sir Dudley de Chair KCB KCMG MVO, who had commanded the 10th Cruiser Squadron out of Scapa Flow in World War One, maintaining the Northern Patrol. That evening he hosted an official dinner for the Flag Officer and Captains and there was a ball at Sydney Town Hall for 500 Petty Officers and men.

Another 240 attended a dance given by ex-service women and sixty officers danced the night away at the Rose Bay Golf Club. There was a dinner and a theatre party for senior sailors hosted by the Overseas League. This was just day one of a ten-day programme, every day of which was equally packed with events and entertainments.

There was keen competition in the hosting stakes. Even the State Premier, Sir George Fuller KCMG, had needed to head off a Federal attempt at gazumping a dinner one night for the squadron’s senior officers. Curtly saying that the Federal suggestion was not welcome he pointed out that the dinner was at the Australia Club, he was a member of that Club, and he had been ‘first in the field with the invitation’.

Hood’s ‘At Home’ on April 10th hosted 1200, the Commonwealth Government gave a banquet and hundreds of men were taken to tourist spots and beaches. Of the numerous sporting competitions Fleet Boxing proved a particular crowd pleaser. A further 156,000 visited the battlecruisers, which meant that during their time in Australia 10% of theAustralian population had physically stepped aboard the British ships, and possibly another 20% observed them in harbour or on passage.

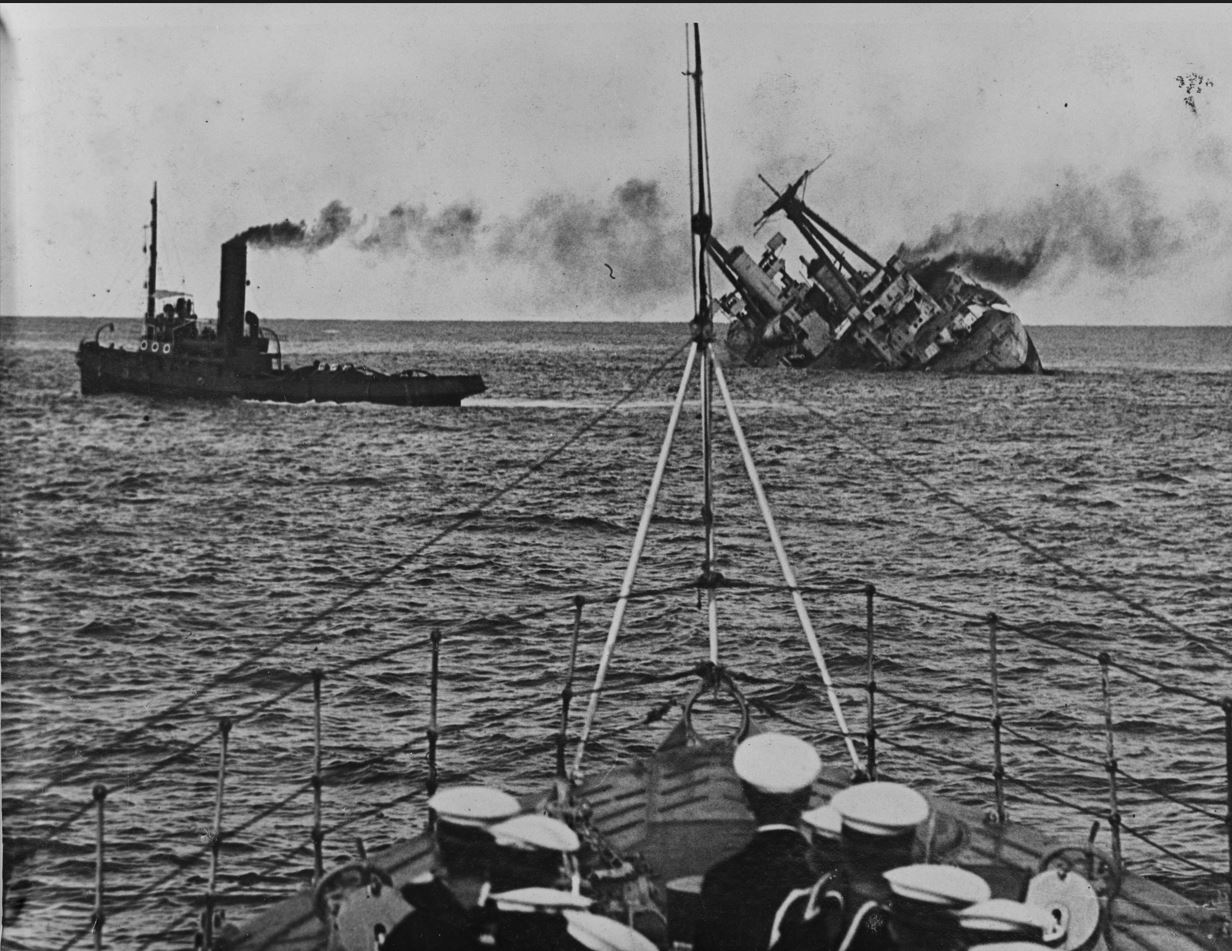

On the evening of April 11th squadron searchlights lit up the harbour and city. The next day Hood saluted a decommissioned Australia as she passed by under tow and out to sea. Her scuttling had originally been planned for Anzac Day but had been brought forward so that the visitors could participate. Observing were the light cruisers HMA Ships Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane with flotilla leader HMAS Anzac and the torpedo boat destroyer HMAS Stalwart. The cruisers of the Special Service Squadron saluted as they steamed past in line abreast either side of Australia as she settled and heeled over. Lieutenant Humphries in HMS Dragon recorded that: ‘This is the day of the sinking of Australia. All the people are very sad about it.’ Sad certainly, but the Minister of Defence, responding to criticism about the fate of the battlecruiser, stated: ‘The whole of Australia believed in that Treaty being observed if it meant bringing us nearer peace than war’.

On return to harbour the parties continued. The Premier in his farewell speech declaimed: ‘If we ask ourselves how it is that for 136 years, 12,000 miles from the Motherland, we have been able to hold one of the richest prizes in the world, our answer is supplied by these ships in our harbours today’. The Lord Mayor chimed in with a plea for immigration to increase the population, the same plea which had been explicitly made in every state visited.

The Prime Minister’s farewell speech fulfilled every desire of the First Lord, the First Sea Lord and Sir Maurice Hankey when he said: ‘It is not enough to express gratitude. It is necessary to show Australia is determined to shoulder her fair share of the burden of our common defence’. With the public acclaim engendered by Hood on her visit he was now confident enough to publicly proclaim the commitments made at the Imperial Conference. First would be the construction of two ‘Treaty Cruisers’ as recommended by the Admiralty, at 10,000-tons and with 8” guns the heaviest vessels with the largest armament allowed cruisers by the Washington Treaty.

When the squadron departed for New Zealand it added Adelaide to its strength. Nicknamed ‘Long Delayed’ because a period of seven years had elapsed between her laying down in 1915 and her commissioning in 1922, Adelaide was the first of the cruiser exchanges that the Committee of Imperial Defence had advocated. Avery was also hoping that their presence in the Canadian portion of the cruise would provide a good example, since Canada had yet to endorse the proposals of the Committee of Imperial Defence for their navy, as Australia had just so unequivocally done for hers.

In 1925 the new Australia and Canberra were laid down at John Brown’s shipyard and commissioned in 1928. When the seaplane carrier HMAS Albatross commissioned in Sydney, and the new submarines HMA Submarines Oxley and Otway arrived in 1929, much of this construction committed to after the visit of Hood and her Special Service Squadron had been overseen by Engineer Rear-Admiral Ernest Sydenham CBE, the navy’s Director of Engineering for eight years from 1923 to 1931.

Postscript

‘Freddie’ Field, an officer who had been wounded and Mentioned in Despatches leading a raiding party ashore during the Boxer Rebellion, was also noted for entertaining guests with conjuring and magic tricks during formal receptions. Reported post-cruise ‘as having the ability to uphold naval interests in high official circles’, he was confirmed in rank as a Vice-Admiral. Already a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, usually given for senior military service, the Admiralty and the King were pleased enough to have him graciously raised one in the knighthood stakes for his Empire Cruise services. The day after the cruise officially ended in Devonport on September 29th, 1924, he was made a Knight Commander of St Michael and St George, an order generally reserved for diplomatic service.

Of the two capital ships in the Special Service Squadron Hood was destroyed at the Battle of the Denmark Strait on May 24th 1941. There were only three survivors, and among the 1415 men lost were four Australians. Repulse, along with HMS Prince of Wales, was committed by Churchill and the Admiralty to concentrate a British Battle Fleet in Asia in accordance with the strategy touted to Australia in 1923-1924. They went down together in December 1941, with over 500 of Repulse’s crew killed in action.

The cruisers HM Ships Dauntless and Danae survived World War Two. HMS Dunedin was operating in the Atlantic in 1941 when she was sunk by U-124. There were only 67 survivors of her 486 strong crew. With many New Zealanders serving aboard it was a tragic day for the RNZN. Dragon, the last warship to escape Singapore before its surrender, was hit by a manned torpedo during the Normandy operations and, on scuttling, become part of Mulberry Harbour. Delhi, which had been commanded by an RAN officer during the Spanish Civil War, had such extensive battle damage by war’s end that it was considered uneconomic to repair her and she was scrapped.

In British service Oxley was sunk in the opening month of the war, Albatross would be torpedoed off the Normandy invasion beaches, and Otway survived to be paid off at war’s end. Canberra was sunk at the Battle of Savo Island; Australia went on to earn more battle-honours than any other RAN ship in World War Two.