- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Yarra II

- Publication

- June 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

After lying dormant for many years a 73 year old letter written by a survivor from HMAS Yarra II has recently surfaced.The original recipient of the letter, George Vooles died in June 2006 when his wife Val gave a file containing George’s service records, including the letter, to their daughter Vicki Hansen. Her husband Paul Hansen, who has contacted us through the HMAS Yarra Association, is interested in finding out if any of our members might have any further information on this topic.

In 2013 the unique honour of a Unit Citation for Gallantry was awarded to the crew of HMAS Yarra II for: ‘Extraordinary gallantry in action off Singapore on the 5th of February 1942 and in the Indian Ocean on the 4th of March 1942’.

In overview the sloop HMAS Yarra was lost in the Indian Ocean following a gallant action against overwhelming enemy odds in March 1942. Before this Yarra had been involved in evacuations from Singapore and was now assisting the Allied forces based in Dutch East Indies.

Yarra, under the command of LCDR Robert Rankin, RAN and the Indian sloop HMIS Juma were escorting a convoy of three tankers Francol, War Sirdar and British Judge, the depot ship HMS Anking plus two small minesweepers, HMS Gemas and MMS 51 from Batavia through the Sunda Strait towards the southern Javanese port of Tjilatijap. In the early hours of 28 February disaster first struck when War Sirdar ran aground and the corvette HMAS Wollongong, which had joined the convoy, was detached to stand by the stricken ship. Despite repeated efforts to tow the tanker off they were forced to give up due to enemy air attacks.

After clearing the Strait news reached them that defence of Java was untenable and Allied ships were to make for the comparative safety of Australia and India. Juma and Wollongong with British Judge were ordered to return to Colombo and Yarra and the remainder of the convoy to turn south for Fremantle. The auxiliary minesweeper HMS Gemas which had insufficient fuel for the voyage was detached to make for Tjilatijap.

With one ship from the convoy already torpedoed, but still afloat, the speed of advance was limited to about 9 knots. Late on 2nd March they had been discovered and for a short time were shadowed by enemy aircraft. The next day the sails of two lifeboats from the sunken Dutch merchantman Parigi were sighted and about 40 survivors were brought aboard. That night a submarine contact was reported and Yarra dropped depth charges, but no further contacts were detected. In calm seas they settled down looking forward to being home in Australia in about four day’s time.

Yarra’s final stand

The following morning, 4th March, they awoke to a beautiful clear day; just as hands were about to go to breakfast alarms sounded for action stations as flashes from gunfire had been observed on the horizon. A few seconds later 8-inch shells roared overhead and all around them. They had come into contact with Vice Admiral Kondo’s formidable strike force of three heavy cruisers and three destroyers. Only a miracle could save them.

LCDR Rankin put the helm over, sent an enemy report and ordered the convoy to scatter. Yarra then laid a smokescreen between herself and the convoy and, in the best fighting traditions of the service, made full speed to engage the enemy. One by one the ships of the convoy were picked off and eventually Yarra, now a blazing inferno, was forced to abandon ship. Of her complement of 151 plus those from Parigi, a total of 34 made an uncertain escape into two Carley life-floats and two smaller box floats plus other supporting flotsam.

Yarra’s ships boats had become a splintered mess during the engagement but she was fitted with two Carley life-floats and two smaller box floats. There are two types of Carley floats, the larger is 10 foot long x 5 foot wide capable of supporting 20 men, and the smaller version is 8 foot long x 5 foot wide supporting up to 18 men. The box floats are 3 foot x 3 foot and capable of supporting 8 men. It is not know which type of Carley float was on board Yarrabut assuming the larger this gives a maximum life saving capacity for 56 men. The problem with the floats is they can only accommodate about half this number inside the float with the remainder staying in the water clinging precariously to rope beckets attached to the sides to the floats.

While some survivors from the convoy were rescued by other vessels those from Yarra were not sighted until 8th March. By this time many had died of dehydration and exposure, only 17 (13 ex Yarra, 1 ex Parigi and 3 from other ships – the Parigi survivor died before reaching Colombo)were eventually rescued by the Dutch submarine K-X1,and initially taken to Colombo. Listed amongst the survivors is Acting Leading Stoker D.L. Stevenson. After about five week’s hospitalisation and recuperation the survivors were returned to Australia in various ships, with Stevenson transferred by HMA Napier to Fremantle.

Other known survivors from the convoy included 57 men from HMS Anking rescued by the Dutch merchantman Tawali and taken to Colombo. Another Dutch ship Tjimanoek rescued 14 survivors from MSS 51 taking them to Fremantle.

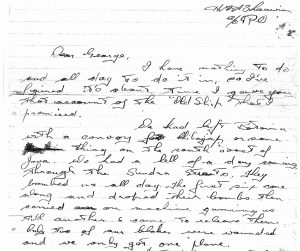

The Stevenson Letter

The twelve page letter by Duncan Love Stevenson, handwritten shortly after these dramatic events, when he was convalescing at HMAS Leeuwin is important. His words to his friend George Vooles, a Telegraphist then serving at HMAS Maitland (naval depot at Newcastle, NSW), provides a blunt assessment as witnessed by one of the few survivors, all of whom were from the lower deck. While the letter is not dated it was sent from Leeuwin, where Stevenson was posted (medical) from 11 April 1942 to 18 May 1943, and addressed to Vooles’s home in Perth. If written between these dates it is almost a contemporaneous account, whereas G. Hermon Gill’s measured official history The Royal Australian Navy 1939 – 1942, was first published in 1957, many years later.

Ldg Stoker Duncan Stevenson – family archive George Vooles – family archive

The following manuscript has been retained in its original format other than for a few minor grammatical changes and some illegible words, with an educated guess taken on suitable replacements. There are some discrepancies against the official historical record and those used by Stevenson. Stevenson says the Japanese strike force comprised four cruisers and three destroyers, – for purposes of accuracy the official version has been used. The numbers rescued from SS Parigi are also in dispute, in this instance as he was an eyewitness, the numbers provided by Stevenson have been used.

HMAS Leeuwin

c/o GPO

Dear George,

I have nothing to do and all day to do it in, so I’ve figured it’s about time I gave you that account of the ‘Old Ship’ that I promised.

We had left Batavia with a convoy for Chiloyap (Chilachap) or some such thing on the south coast of Java. We had a hell of a day coming through the Sunda Straits. They bombed us all day. The first six came along and dropped their bombs then carried on machine gunning us till another six came to relieve them. Only two of our blokes were wounded and we got one plane.

That night we got clear of the Straits and were attacked by subs, we lost a tanker and got a sub. The next night we reached our destination but we couldn’t go in ‘cause the Japs were there. We were told to nick off home, and we didn’t argue.

Next night we picked up two boat loads of survivors from a Dutch ship (36 Javanese & 4 Dutch). The next day was uneventful. The following morning 4th March between 6.15 and 6.30 we sighted three cruisers, four destroyers and three aircraft. We laid out a smoke screen and told the others to nick off, while we done them over with our three 4-inch guns. The Japs had more than twice the speed of any of our ships. There was only one Pussers ship in the convoy besides us that was a motor minesweeper mounting one machine gun. First hit, after a dozen misses, was on the bridge. It turned the direction platform up, further up the bridge and made a hell of a mess of two guns crew. Next we stopped one on our third gun that split it in bits and killed all its crew. With only one gun firing we made for one of the cruisers to ram it, but that failed when we stopped with one in the engine room. A few more hits and we were just about buggered. The ready use locker on one gun blew up. The order was passed to abandon ship. The sick bay was crowded and the doctor dashed down to help those out. He had only just got there when a shell exploded in there. We didn’t get any of the boats off, what was left of them wasn’t worth worrying about.

We had to swim through a hail of shells and shell splinters to get to the Carley floats. After we got out of the line of fire, we tried to get together as best as we could. Some were on box floats (about 5’ x 2½’) some on bits or wreckage, others on fuck all. Well there were 33 of us on the two (C) floats and a couple on box floats when a Jap destroyer stopped about a hundred yards from us and lowered a ladder. The mob was undecided about swimming to it at first. We figured that our SOS would be answered even though we were more than 300 miles from Java and about 200 from Aussie. However they pulled up the ladder and lowered a boat but this only came halfway down, then was taken inboard again. A heavy sort of machine gun was trained on us then, but he saw somebody go and speak to the gunner (they probably decided not to waste their ammunition). The ship got underway and left us to it. With two gallons of water and no food we settled down to wait for further developments. That afternoon we found a tin of Pussers biscuits and I can assure you I was never more pleased to see Pussers biscuits. Some of us brought tins of cigarettes which were sealed. We had matches too but attempts to dry them failed. Having cigarettes without matches isn’t such a pleasant thought in such a position so we ditched the cigarettes.

We decided not to open the biscuits that day as we still had the taste of the previous day’s bully beef in our mouths (we were sunk before breakfast).

Night came and still no sign of being picked up. Next morning, we had no sleep ‘cause we had to sit up and the water came up to our chests, we saw a convoy not far away. The gear provided with the Carley floats for attracting attention (torches, smokers and flares) were spoilt by the water. Our only hope was to use the reflection of the sun on the biscuit tin, but this was unsuccessful, the convoy kept going. In the afternoon, we sighted a lifeboat and started to paddle towards it. After an hour or so of this we met a Chinese bloke on a fair sized raft we figured on putting some of our blokes on it to lighten the load on the float, but the Chow couldn’t wait for us to get along side it, he swam the last 50 yards or so and the tide took his raft away from us and we couldn’t catch it, so we were left with an extra man to feed and a heavier load. Towards sunset we lost sight of the lifeboat. The night passed slowly and was very cold. Just before dawn, another ship passed us this day (Friday) and we could not attract their attention. We were feeling pretty hungry by this time. We had had a biscuit each about a dessert spoonful of water on Thursday and the same on Friday. After another weary night Saturday morning brought tragedy to our little bunch. Some of the mob, started to go mad. They saw things that weren’t there and told everyone about them. Things that we needed most: food, drink, boats, all the luxuries about the place came into their minds.

Lofty Edwards (you met him at the Leederville dance) was the first to go over, the tide was pretty strong and it took him away. In the tussle the float was turned up and we lost a lot of biscuits and water. Five of us took a box float and went after Lofty. He was in a bad way when we got him on the float. One of our chaps decided we were getting too far from the mob so he left us, we tried to get onto the float and pump him out, but it wouldn’t work, there wasn’t room, every attempt only tipped it over and we had a hell of a job to put Lofty back as he was unconscious. When he died we shipped him into the water. To swim back to the Carley was a job too big for me to tackle in my weakened state as the tide was running the wrong way and it was a matter of about 200 yards. The other three set out for it and I climbed on the box float and went to sleep almost immediately. In the afternoon I woke up and heard somebody shouting for help. Then I seen two of the blokes who were with me earlier, I got one of them onto the (B) float but the other went down. Sandy went to sleep (or passed out I cannot tell) as soon as I got him onto the float. Towards sunset I saw a ship coming towards us, so shook Sandy to make sure that it wasn’t imagination but he didn’t move. The ship came and passed, but it was too far away for them to see us. After dark I heard Sandy say that he wanted to go to his girlfriends place up the road. To stop him swimming away I had to suggest paddling the float with me till we got to the top of the hill. However after a while he declared we had arrived at the gate and pointed out to me that the house was a fair way back from the gate. He talked about this house so much I began to see it too and after a while I could even see people walking about inside, quite a long time passed and we weren’t making any headway so he developed a rush of blood and wanted to swim for it. I felt too tired to swim that far and decided to sleep on the float for a while. Thinking the float couldn’t drift far cause there was a fence around the house and the moving tide might take me inshore. However he didn’t want to sleep with half his body in the water so I let him go. Little did I think that I wouldn’t see him again. I climbed aboard and went to sleep.

I woke up during the night and my brain was quite clear again and I realised once again that I was in a bad way. Three days had passed and I had only eaten two biscuits and had only drunk about two spoonful of water (which was measured out in a top of a pencil torch). I laid down and slept again. This time I dreamed. I was back on the ship sitting on the mess deck and my cobber Freddie Harding was telling me that I looked thirsty and he had some lemon squash in his locker and I could pig out on it. But when I got up to go for it I woke up and found myself sitting up on my float. After a while I tried to sleep again but the same thing happened over again. This was repeated several times during the night. Finally I struck on the idea to ask him to get it for me, he did and I enjoyed the drink, the remainder of the night passed in peaceful sleep. I woke after sunrise and had a look around but nothing offered to break the monotony bit it wasn’t long before I noticed a shark swimming about me. I drew my legs up so he couldn’t get them. He was quite playful, it even came to the surface and flapped his fin on my float which only stood about two inches out of the water. The hours went by and it still hung around. It was getting towards midday when I saw a lifeboat a few hundred yards away. I had to put my feet down to paddle towards it and had to draw them up whenever the shark looked like having a nip. I paddled for a long time and the distance between us was down to little more than 50 yards, I could see men on it. I got a bit anxious about it and took my eyes off the old shark at the wrong time and he got hold of my foot. However he didn’t get hold of it properly and opened his mouth to get a better grip and I pulled my foot away and seen him off, but it still hung around.

A while later a sub came up between the boat and me. They answered my wave so I figured everything was OK but when they picked up the blokes in the boat they got underway and turned their backs on me. That was pretty hard to take, but I consoled myself with the thought that it was a Jap sub and seeing the nationality of the blokes they picked up, considered it not worth while worrying about me, so I laid me down to sleep it off. Next thing I knew a rope landed across my gut, but I figured that I was having another turn so I chucked it away, but when it came a second time I thought it best to look see. The sub had turned back to pick me up. I just managed to climb aboard but had to be carried along the deck. The officer on the bridge gave me a sip of hot milk, but I reckoned he was a bit slow on the game so I snatched it off him and tried to put it all down at once. It must have been funny cause they near shit themselves laughing at me. I tipped it all down the wrong side of my guts (the outside). They passed me down the ladder to the main deck by the clock there it was 1730 and the day was Sunday 8th. They took my overalls off and ditched them, then gave me a pair of underpants and put me to bed.

It took another seven days to get to Colombo. On board the sub things weren’t the best. We lived on rice, had to eat, sleep, shit and wash in the same little compartment but the crew lived under the same conditions and done their best to make us comfortable, they gave us cigarettes although we could only smoke in the evening when we came to the surface. On arrival in Colombo we went ashore in the same underpants and nothing else. There were 17 of us, 13 of our crew, Dutchman who we had picked up before we were sunk (this bloke had been sunk three times in that fortnight). The others were from one of the ships in the convoy. At the hospital they gave us all we needed to carry on with including 100 Rupees. Had about a fortnight in hospital getting treatment for salt sores, etc. Then went to a rest camp up the country to wait for a boat home. We returned home via Mauritius and got 14 days survivors leave and 28 days foreign service leave.

Well I reckon that will just about do for that lot. I’m back in depot getting treatment for my foot. I’ve been on a trawler since I came back. Here’s wishing you all the best.

The letter is signed – Steve.

Notes:

- Recently Paul and Viki Hansen have managed to trace Duncan Stevenson’s son Richard who with wife Mel now live in Queensland and are in contact with other of Duncan’s relatives in Western Australia.

2.The original of Duncan’s letter has now been passed for safekeeping to the Australian War Memorial’s Private Records Collection.