- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, Biographies and personal histories, Naval history

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Marsden Hordern

Mary Bryant nee Broad

This is the story of Mary Bryant, the convict woman with two babies who in 1791 helped steal a naval cutter in Sydney and sail it to Timor in an open boat voyage. This remarkable feat of endurance and navigational skill was just as prodigious as the widely acclaimed one of Captain Bligh after the mutiny of the Bounty, and in a seaman’s world she was as good as the best of them.

This is also a true story touching on crime, punishment, love, hardship, perseverance, bravery and even fills an important gap in the history of charting our continent by attributing the discovery of over 200 miles of the north-eastern Australian coast to the convicts Mary and William Bryant.

Mary was from a Cornish seafaring family, born with the sound of the surf in her ears. She was baptised at Fowey on 1 May 1765, the daughter of William and Grace Broad. The Broads also had a sideline in sheep smuggling. This young woman emerges as tough, illiterate, courageous, forthright and practical. She was good looking and at 5 feet 4 inches in height, above average for these times, had clear grey eyes and a pale complexion set off by the flowing tresses of a Pre-Raphaelite beauty.

Mary left home when aged 19 seeking work at Plymouth. Here she fell in with bad company and was arrested with two female accomplices and charged with highway robbery of a silk bonnet, jewellery and a few coins. Mary was convicted and sentenced to death, later commuted to transportation for 7 years.

William Bryant

William was born in April 1757 to William and Jane Bryant, fisherfolk who with many of their contemporaries were involved in smuggling. To fishermen a little smuggling was a way of life which aided them and the local economy. It was part of a much wider problem of high duties being charged on mainly French imported goods – ironically a form of taxation necessary to pay for the increasingly expensive French wars. Some sources say William was arrested for smuggling, but he was charged with impersonating two Royal Naval seamen in order to obtain their wages, and sentenced to 7 years transportation.

At the time of both William and Mary being taken to the transportation hulks they would have expected to call America home. But with the War of Independence the system of transferring undesirables offshore was in limbo until the decision was made to open a penal settlement at Botany Bay. Eventually they both found themselves aboard the transport Charlotte, one of the First Fleet bound for the largely unknown New Holland. As a prisoner in Charlotte William was employed in issuing provisions, indicating he was literate and resourceful and regarded as trustworthy. On the voyage Mary was discovered to be with child and a fine girl they named Charlotte was baptised by the Chaplain when the Fleet reached Cape Town.

Now needing a protector, Mary agreed to marry the handsome William and they were joined together at one of the first weddings performed in the new colony. Food was desperately short and as he was an excellent seaman William Bryant was given charge of Governor Phillip’s six oared cutter, had a hut built for him and Mary on Bennelong Point, and with five other convicts spent much of his time fishing for the government stores.

In 1790 Mary had her second baby, a boy, christened Emmanuel by the chaplain. Things were beginning to look up for the Bryants. They were trusted, might well have been subsequently emancipated, given a grant of land and become one of Australia’s pioneer founding families. But their tendency to vice was ingrained. William began privately selling part of the government’s catch; he received one hundred lashes and when cut down from the triangle his back was a bloody mess, torn by the strokes of nine hundred knotted cords. William was dismissed from his position, but his skills being found indispensable, a few months later he was back in his old job. This time he was embittered and seeking vengeance.

The Escape Plan

Mary now longed to escape from Sydney with her family and they began a plan to steal the cutter and sail her to Timor. Seven convicts were chosen wisely for their strength and skills, one with navigational skills joined them and another, a bricklayer and stone mason, was literate and became the planning expert. Luck was also with them as the cutter had recently been overhauled, had new masts and replacement lug and foresails, oars and a good supply of provisions, including fishing nets.

In October 1790 the Dutch ship Waaksamheyd,which had been chartered in Batavia and captained by Detmer Smith (Smit), arrived at Port Jackson loaded with badly needed provisions. Royal Naval officers found the gruff old Dutch sea dog difficult and unprofessional, and the relationship between the parties deteriorated. However the ever helpful William became friendly with the Dutchman. In those days it was not unusual for ship masters to have a minor share in the ownership of their vessel and to have some trading rights on their own account.William persuaded Captain Smith to sell him for 15 rix dollars (then widely used as international currency) a chart, compass, quadrant, two muskets with powder and lead and 100 pounds of rice. Detmer also provided information on sailing directions to the Dutch East Indies. Captain Smith may have taken this opportunity to pay back the superiority of the local naval officers who looked down upon him.

The momentous journey begins

The conspirators managed to save and purchased additional provisions, most importantly 100 pounds of flour and fourteen pounds of pork. At about midnight on 28 March 1791 they slipped silently out of Sydney Heads and steered north on what was to be a hazardous open boat voyage of over 3,000 miles. But they expected favourable winds as they had left at the time of the year when the South East trade winds were beginning to blow.

A ‘naval cutter’ was a utility open boat used for going from ship to shore taking personnel, provisioning and/or the important task of laying out kedge anchors. As a pulling boat it was rowed by pairs of oarsmen sitting side-by-side on each thwart and carried a removable rig for sailing in favourable winds. Cutters were typically 22-29 feet long with a 7 foot beam, a fairly straight sheer from bow to stern and a shallow keel.

They divided the twenty-six foot boat into three sections. Four men lived in the first 12 feet, three in the next seven, and the rest was reserved for William, the nursing mother and her two infants. Two days after leaving Sydney they ran the boat ashore near the mouth of the Hunter River where Mary brewed some ‘sweet tea’ from the leaves of a native plant and they found lumps of coal which burned as well as any they had known in England. This discovery of coal in Australia was six years before that attributed to George Bass at Coalcliff, south of Sydney. Two days later they entered today’s Port Macquarie, repaired their leaking boat with beeswax and resin, filled their water barrel and hoped to rest and stretch their legs for a day or two but they were attacked by spear throwing aborigines and driven out to sea. There, caught by a rising gale they were driven out of sight of land for several days, seas broke over the boat and they had to bail constantly to keep afloat. When they approached the shore again the high surf prevented their landing and they anchored outside the breakers. At 2 am on a dark morning the anchor rope parted with a heavy shock, the men took to the oars, and water broke into the boat. All now gave themselves up for lost except Mary, who, calling out ‘never fear’ seized one of the men’s hats and started bailing. They followed her example and survived.

Their perilous voyage continued. For weeks they sailed on, sometimes meeting friendly blacks, sometimes attacked with showers of spears, until entering the waters of the Great Barrier Reef nature softened and they sailed in calmer waters, pushed along with the South East trade winds singing in their sails. Flying fish sped before their bows on glittering wings, and at night the sky above their mast was ablaze with great lights in a display of sparkling jewels more brilliant than any found in a king’s ransom.

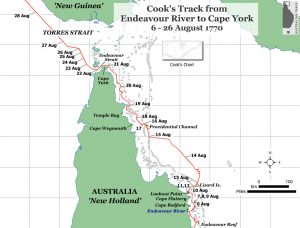

The reef waters now helped sustain them. On one island they caught six turtles and feasted on them for days, and when they were down to their last gallon of water in a heavy shower they caught twelve more gallons in their sails. They followed in Cook’s wake as far as Endeavour Reef where the great navigator’s ship fell foul of the razor sharp pinnacles of coral and was forced to seek refuge to make repairs. Cook considered this portion of the reef too hazardous and next proceeded outside the reef before making a return through Providential Channel to safe water and thence through the Torres Strait. The convicts however stuck to the inner passage all the way to Cape York, making them the first known Europeans to have traversed the full extent of the Barrier Reef and in doing so they navigated over 200 nautical miles where no sail had previously passed.

It would be interesting to speculate if our convicts, mainly from the ship Charlotte with baby Charlotte onboard, when on this passage from Lizard Island and rounding Cape Melville proceeded directly to Cape York or followed the coastline, as there is a large then unknown indentation, Princess Charlotte Bay. The bay was not named until after the survey of this part of the reef conducted by Lieutenant Charles Jeffreys in HM Brig Kangaroo in 1816-1817.

When they reached Cape York dreadful danger awaited them. The ferocious cannibals of Torres Strait in their big fast sailing war canoes and armed with deadly bows and arrows were alert, and one morning the cutter’s crew was horrified to see that they were being chased by two big war canoes each manned by thirty or forty men, and once more Mary and her companions had to fight for their lives; this time not against the implacable sea but against malevolent man in a desperate attempt to escape from the cannibals’ cooking pots. Their muskets when fired did not deter their pursuers. The winner in the coming race would be the one which could sail closest to the wind, and for all their speed down and cross wind the cannibals had a formidable opponent in a Royal Navy cutter built in a eighteenth century British dockyard and sailed by William Bryant. Her taut sails, the grip of her keel in the water, and his sailing skills saved them. The cutter began to forge ahead, and slowly the war canoes dropped astern and were lost to sight.

This narrow escape ended their hopes to stop for a day or two on an island, rest, and look for food. They held on westwards across the Gulf of Carpentaria on a voyage of a thousand miles towards the island of Timor in the Dutch East Indies. After clearing the Gulf they did make one stop running ashore at Arnhem Land and discovered a fresh water river where they filled their casks before continuing under the burning sun on the three hundred mile crossing of the Timor Sea. Everyone was now suffering the effects of exposure and poor food, and as Mary was unable to feed baby Emmanuel he was just wasting away.

Deliverance and the Dutch East Indies

Day followed day, their hopes sank lower and lower until one day in early June Mary thought she saw a bank of clouds on the western horizon; she looked again, there were Timor’s mountains and on 5 June 1791, after a sixty-nine day voyage of 3,254 nautical miles, they reached Koepang and represented themselves to the Dutch Governor, Timotheus Wanjon, as shipwrecked castaways. Bryant wrote an account of their voyage for the Governor but unfortunately no copy of this account has since been found. The similarities between the voyages of Bligh and Bryant are remarkable. Bligh and his 18 companions were cast adrift in a slightly smaller 23 foot open boat and took just 47 days to complete a journey of 3,618 nautical miles taking them through the Torres Strait and ending at the same destination of Koepang two years earlier on 14 June 1789.

Time now passed pleasantly for Mary and her companions. They were comfortably housed, their health quickly improved, and they were fed and clothed by bills drawn on the British Government. But there were some things about these castaways that did not ring true to the discerning Dutch. They were in no hurry to catch a ship back to England, the men had the scars of many floggings on their backs, and when one of them while drunk betrayed their secret they were lodged in the castle at Koepang under surveillance as suspected escaped convicts.

Their secrets discovered

Fate then dealt them a severe blow. The British frigate HMS Pandora had been wrecked in Torres Strait a few weeks before and her Captain Edwards with two boat loads of survivors plus ten of the Bounty mutineers arrived in Koepang. Edwards interrogated the convicts, and had them clapped in irons, and as soon as a ship arrived took them with him to Batavia to await a further passage to England to be charged with being escaped convicts.

In fever ridden Batavia some of the party contracted malaria and on 1 December 1791 Emmanuel died in Mary’s arms to be followed three weeks later by William, the husband for whom she had dared and suffered so much. From Batavia the shrinking band was shipped with the Pandora’s survivors in the Dutch ship Horssen and as they entered Sunda Strait, one of the cutter’s crew James Cox, knowing the noose awaited him, leaped over the side to his death in its shark infested waters. Before they reached Cape Town two more of his companions had died of fever.

In Table Bay Mary and Charlotte were transferred to the frigate HMS Gorgon, and by chance also aboard her was Captain Watkin Tench, a marine officer from New South Wales who had been in the ship Charlotte in which Mary had been transported. He remembered her and had been in Sydney when she had escaped in the cutter, which he described as ‘a very daring manoeuvre’. No one in Sydney had expected them to survive and he had admired their enterprise. Tench was a compassionate man, and as he looked on her anguished face as she tended her sick daughter he confided in his journal:

It was my fate to fall in again with part of this little band of adventurers in March 1792, when I arrived in the Gorgon at the Cape of Good Hope … I confess that I never looked at these people without pity and astonishment. They had miscarried in a heroic struggle for liberty, after having combated every hardship and conquered every difficulty … and I could not but reflect with admiration at the combination of circumstances which had again brought us together to battle human foresight and confound human speculation.

The Gorgon sailed northward into the Atlantic and every day Charlotte lost a little more of her fragile hold on life until a broken Mary held in her arms the body of the last she loved. Charlotte was buried at sea, the officer-of-the-watch duly recording in the ship’s log:

Sunday, May 6, am at 6 Departed this life Charlotte Bryan (sic), daughter of Mary Bryan, convict aged 4 years.

The return home and Newgate Gaol

Five of the original eleven escapees reached England and on 5 July 1792 were committed to Newgate Gaol charged with being escaped convicts. They expected no mercy but reckoned without the power of public opinion which often salutes courage and sides with the underdog. The story of their adventures and sufferings aroused such interest that articles began to appear in the press and the matter was taken up by James Boswell (1740-1795), barrister of the Inner Temple, the famous biographer of Samuel Johnson and a man much given to defending the destitute. He interviewed the prisoners, offered to defend them, and on 2 May 1793 Mary received an unconditional pardon. Boswell gave her money to return home to live with a sister in Cornwall, saw her on board a ship for the coastal voyage from London to Plymouth and promised her, if she behaved well, an annuity of ten pounds (£10). This promise appears to have been maintained with the funds forwarded via a local clergyman.

The male prisoners were released and pardoned in late 1793 thanks to the advocacy of Boswell. One of them unexpectedly enlisted in the NSW Corps (possibly saying something about the selection process) and promptly set sail again for Botany Bay.

As Mary could not write, she dictated to Boswell the story of her eventful voyage. It was found among Boswell’s papers together with a small packet of withered leaves of the false sarsaparilla plant which Mary had picked from a vine near the mouth of the Hunter River and was labelled in Boswell’s hand ‘Leaves from Botany Bay used as tea’.

We are not sure what became of Mary but she deserved well. The Australian historian Dr George Mackaness states in his monumental Life of Vice Admiral William Bligh that she married again to one of the officers who returned to England with her in the Gorgon and if so, he was a fortunate man for she was a remarkable and courageous woman.

This should have been the end of the story but in recent times another important first-hand account of the voyage has been discovered amongst the papers of Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) held at the University College, London. Bentham was a philosopher and social reformer who took a determined stance against transportation of convicts. A memorandum believed to have been mainly written by James Martin (one of the original escapees with the Bryants and in charge of planning the enterprise) when he was arraigned at Newgate Gaol in 1792. Following the release of the prisoners this document appears to have been acquired by Bentham and as it largely collaborates and says little that has not already been exposed by Boswell it lay dormant. The papers have however now, in 2014, been edited by Tim Causer and published by the University College, London.

We who have followed, thanks to the perseverance of those involved in those far distant times, and now live in a rather pleasant land in much easier circumstances might ponder and reflect for a moment upon this tale. Was Mary just a girl on the make, an opportunist, or was she our first magnificent heroine?