By Peter Dunn OAM

The Dutch submarine K IX is known to many who are familiar with the Japanese midget submarine attack in Sydney Harbour on the night of 31 May 1942. Submarine K IX was berthed outboard of HMAS Kuttabul when it was sunk. K IX suffered significant damage and crew members were injured. In this story Peter Dunn outlines the full service history of K IX which is lesser known. This story is republished with the kind permission of Peter Dunn OAM, “Australia @ War” www.ozatwar.com.

Royal Netherlands Navy submarine K IX was commissioned on 21 June 1923. It arrived in the Dutch East Indies on 13 May 1924. After Germany attacked the Netherlands on 10 May 1940, K IX was patrolling Dutch East Indies waters. In March 1941, submarines K IX, K X and K XVII were ordered to the Sunda Strait because the German “pantser” ship Scheer was seen in the Indian Ocean and had attacked several merchant ships.

In early December 1941, K IX whilst being repaired in the Naval Yard at Soerabaja, was struck from the Active List. The Netherlands declared war on Japan after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. The crew of K IX were transferred to K X so that it could return to Active Service.

On about 6 January 1942, K IX is recommissioned using reserve personnel from the Soerabaja Submarine Base and returned to Active Service in March 1942. K IX was forced to return to port for engine repairs during a war patrol in the Gulf of Siam. She escaped Soerabaja on about 2 March 1942 before the Japanese invaded and escaped to Fremantle in Western Australia arriving there on 13 March 1942 with seven important Dutch officers on board.

In March 1942, submarine K IX was placed under the operational control of the US Navy in Fremantle. On 1st and 2nd of April 1942, K IX was used as piggy back boat during ASW exercises at Gage Roads, near Fremantle.

On 15 April 1942, K IX was offered to the Royal Australian Navy as a training aid for their Antisubmarine Warfare School. On 20 April 1942, K IX, K XII and the minesweeper Abraham Crijnssen sailed to Sydney via Adelaide and Melbourne for repairs. The RAN accepted the offer to accept the two Dutch submarines on 30 April 1942 and from then on referred to the Dutch submarine as K9 rather than K IX.

K IX, K XII and Abraham Crijnssen arrived in Sydney on 12 May 1942. K IX docked beside the requisitioned harbour ferry HMAS Kuttabul at the east side of Garden Island Naval Base. An inspection of the hull of K IX found it needed some engineering repairs and the machinery, engines and battery were found to be in a poor state of repair. The submarine was due to be refitted at the Garden Island Yard and have a Mark VIII revolving directional hydrophone and an underwater smoke candle gun fitted.

In a letter dated 19 May 1942, Rear Admiral F. W. Coster, the Senior Naval Officer Royal Netherlands Navy in Australia, advised the Secretary of the Naval Board, Department of the Navy in Melbourne, that submarine K9 of the Royal Netherlands Navy would be ready for service on about 25 May 1942. He went on to state:-

“According to discussions I had about this subject with Vice Admiral Royle and Rear Admiral Gould I will instruct the captain of the submarine to report to the officer in command of the anti-submarine school at Sydney, when his ship is ready unless you suggest that other instructions will be given to him.”

At 22:30 hours on 31 May 1942, the Sub-Officer of the watch on submarine K IX reported to the officer of the watch that USS Chicago was firing several shots at something inside Sydney Harbour. The officer of the watch went on deck and noted that the firing had stopped and that the searchlights had been turned off. All the lights at Garden Island were still turned on. The officer of the watch was unable to obtain any information on what the shooting was about.

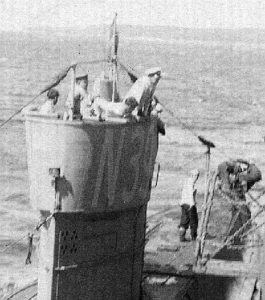

About two hours later at 00:30 hours on 1 June 1942, a torpedo exploded between the dock side and HMAS Kuttabul. The Japanese torpedo, which had been intended for USS Chicago, passed under K IX which was moored beside HMAS Kuttabul and exploded against the sea wall. The force of the explosion sunk HMAS Kuttabul and the shock wave rolled K IX onto her beam ends and lifted her diesel engines off their mounts and damaged the aft batteries. As HMAS Kuttabul sunk it hit K IX and crushed the forward part of its superstructure.

One sub-officer of the watch was blown off the submarine in the explosion and was wounded. The officer of the watch ordered all hatches to be closed and checks for leaks to be carried out. All lines between HMAS Kuttabul and the submarine were cut.

Dutch submarine K IX was towed to another dock at Garden Island. The damaged battery was removed in June 1942 and sold to A.G. Sims Pty. Ltd., scrap metal dealers at Newtown.

It was deemed that repairing K IX would not be an effective use of resources to support the war effort so it was decided to decommission the submarine thus releasing more personnel to meet Dutch Navy needs for more personnel in the UK where new submarines were being built. Permission was received from London to decommission K IX on 26 June 1942 but that did not happen until 23 August 1942.

On 28 June 1942, the Dutch Navy advises the RAN that they intended to decommission K IX. The RAN immediately stopped all repair work on the submarine and K IX was decommissioned on 15 July 1942.

On 27 July 1942, permission was sought from the Dutch Queen to strike K IX and K VIII. The RAN decided to restart work on K IX and used local resources to form a crew. It was eventually manned by a mixed crew of RN and USN volunteers and topped up with some RAN volunteers.

The Queen gave permission to strike both submarines on 17 August 1942 and subsequently K IX was struck on 27 August 1942. Various equipment including a number of electric motors were used from K XVIII on K IX.

In a letter dated 1 September 1942, the Secretary of the Naval Board advised the Naval Officer in Charge, H.M.A. Establishments, Sydney that there was a battery of 112 Tudor Type S.E.37 Submarine cells available in Sydney and that there were enough cells to provide one complete battery of 66 cells and that the remaining cells were proposed to be used in No. 2 Tank in lieu of ballast and be used as an emergency battery.

A letter dated 3 October 1942, from the Commodore-in-Charge, H.M.A. Naval Establishments, Sydney, to the Secretary of the Naval Board, Melbourne, advised as follows:-

Submitted for the consideration of the Naval Board, with reference to Navy Office letter 047433 of 1st September, 1942, the following cells for submarines are available in Sydney:-

(a) One battery of 130 cells received from Western Australia ex H.M.N. Submarine K.8. This battery was sent to Sydney to replace the one in K.9 and is fully charged and ready for service.

(b) 112 Tudor Cells Type S.E. 37 ex Diverted Cargo 447 Tudor Cells Type S.E.37 ex United Kingdom. These are new and not charged; if installed in K.9 it would be necessary to fit new ventilating arrangements as the cells are taller than the original ones. Their output is about 25% less than those fitted previously.

- The submarine was in running order prior to the damage caused by the torpedo explosion. The vessel was docked for examination after the damage and the hull was found to be in good condition externally, except that some of the fastenings for the ballast in the keel were loosened; these were secured.

The main engines and motors have been run frequently since the damage and were used for charging the batteries of K.12; they appear to be in good condition.

- The following is a list of the principal defects, most of which were caused by the underwater explosion:-

HULL

(i) Portion of the light superstructure forward crushed by “KUTTABUL” requires renewal.

(ii) Three watertight hatches and two W.T. doors strained, required fairing up.

(iii) Hole in after battery tank requires repair and lead lining which was renewed for preservation of tank renewed.

(iv) The hull outside the battery tank requires cleaning and painting where the acid escaped. Immediate steps to neutralize the acid and prevent corrosion were taken. The air bottles which were removed for access to the hull require to be replaced and tested.

(v) Torpedo rails and brackets are distorted and require fairing.

(vi) The steering control gearing is stiff and requires to be freed.

(vii) The steel mast requires repair at the base.

(viii) Several pipe clips are fractured and require renewal.

ELECTRICAL

In a number of electric motors fractures occurred to the cast iron end shields and feet. These require repair, viz:-

W/T Generator – feet fractured

Capstan motor – end shield fractured

Periscope motor – end shield fractured

Ballast & trim pump – complete refit and lining up.

Hydroplane motor – complete refit and lining up.

Electric stove – complete refit.

Control board – to be removed for repairs to piping behind it.

All cable clips to be checked and renewed where necessary or broken.

- All the defective machinery was placed on board the vessel after work on it was stopped. The repairs could be carried out locally, but it is expected would take at least six to eight weeks.

- It is considered that, if repaired, K.9 would be suitable for an A/S training submarine.

A letter dated 24 November 1942 from Rear Admiral F. W. Coster, the Senior Naval Officer R.N.N. in Australia advised the Secretary of the Naval Board at the Navy Office in Melbourne that he had instructed his representative in Sydney, Commander Knollema R.N.N. to put submarine K9 at the RAN’s disposal with the ship’s inventory. He stipulated that “unless my Government might decide otherwise – you will have the free use of the submarine as long as you desire, with the understanding that the ship remains the property of the R.N.N.”

On 20 February 1943, the Commander Southwest Pacific Force wrote to the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board advising of the need for facilities for anti-submarine training in the Northern area. He requested that information be obtained from the Senior Netherlands Naval Officer in Australia as to the availability of either K9 or K12 submarines for use in Anti-submarine training in the Sydney and northeast Australia areas.

The transfer of K9 to the RAN nearly did not happen due to a trivial issue involving Australian Customs charging the Royal Netherlands Navy, £39/8/6 duty for the sale of the damaged batteries from K9. Rear Admiral F. W. Coster, the Senior Naval Officer R.N.N. in Australia took exception to this charge and “demanded” that twice that amount be refunded to the R.N.N. or he would have to dismantle the K-9 submarine.

A Teleprinter message dated 13 March 1943 from the Naval Secretariat, Canberra to the Secretary, Department of the Navy, Melbourne (for Mr. Allen) indicated that the Minister for Customs had approved the refund of the £39/8/6 to the Netherlands East Indies authorities in Australia.

The Secretary of the Naval Board at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne wrote to Rear Admiral F. W. Coster on 15 March 1943 confirming that the Minister for Customs had approved the refund of the £39/8/6 duty. Rear Admiral F. W. Coster wrote to the Secretary of the Naval Board on 6 April 1943 confirming he had received the refund.

K9 was finally placed at the disposal of the RAN by the Senior Naval Officer R.N.N. in Australia in mid March 1943. A refit was immediately commenced in Sydney and K9 was placed under the operational control of the Naval Officer-in-Charge, Sydney for anti-submarine training from the Port under the general direction of the Commanding Officer, HMAS Rushcutter. The RAN initially expected to commission K9 in March 1943. A document dated 28 April 1943 showed that it was by then anticipated that the submarine would be ready to commence training duties at the end of May 1943.

Senior Naval Officer R.N.N. in Australia advised on 11 June 1943 that he was happy for the battery from K VIII to be used in K9 however it was on the proviso that if HNMS K-12 should need a replacement battery for any reason the RAN would have return the battery to the R.N.N.

On 22 June 1943 K IX was renamed as HMAS K9 and commissioned into the RAN under the command of Lt. F. M. Piggott RNR.

NOIC Sydney advised on 30 June 1943 that he anticipated that dockyard work would be completed on 5 July 1943. He proposed that the submarine commence being used as a tender to HMAS Rushcutter on 6 July 1943. A period of eleven days was required for tests and trials by ships officers before diving. On completion of those tests, the Commanding Officer requested fourteen days for independent exercises at seas during which time A/S exercise were to be carried out.

On 19 October 1943, it was reported that K9 was still not available for A/S training for US Navy personnel as it had still not completed its conversion and tests. On 27 October 1943 it was reported that K9 was expected to complete engine repairs by mid-November 1943.

In January 1944, the starboard main motor developed a defect. Due to the workload its repair was delayed by at least a month. Lt. Piggott managed to complete a week of exercises using only the port main motor.

At 08:32 hours on 22 January 1944, a major battery explosion occurred in the after section of HMAS K9’s main battery. Fortunately, there were no injuries. 35 battery cells were damaged, 29 cell tops were cracked and battery tank fittings and plates were buckled.

Due to the damage caused by the explosion and all the other outstanding defects, it was decided to decommission HMAS K9 on 24 February 1944 and she was then payed off on 31 March 1944 and returned to the Royal Netherlands Navy.

Conversion of submarine K IX (K9) to an oil lighter was completed in mid May 1945. On 6 June 1945 K IX was towed out of Sydney by the Dutch minesweeper Abraham Crijnssen headed for Darwin. On about 7/8 June the tow line broke in the rough seas. The crew onboard the minesweeper were not aware of the tow line breakage until sunrise on 8 June 1945.

An aircraft was dispatched to search for the submarine. The aircraft located the submarine at 15:00 hours but the search was called off as it was starting to get dark soon. AT 10:15 hours on 9 June 1945 the aircraft refound the submarine but by then the submarine had washed ashore about 3 miles south of Seal Rocks on Fiona Beach on the central coast of New South Wales. Minesweeper Abraham Crijnssen attempted to tow the beached submarine off the shore without success. The Dutch Navy decided the cost of a possible recovery was too expensive so the recovery attempts were abandoned.

The “Commonwealth Disposals Commission” sold the wreck (still on the beach) for scrap iron on 20 July 1945 to Messrs Humphrey & Batt of Sydney for the sum of £985. Locals recovered the diesel engine manually. The new owners recovered the rest of the fuel but not the hull as it was buried too deep to move.

Over the years the hulk of the submarine has been buried by the shifting sands and from time to time it has been exposed. During a large storm in 1974, the wreck was exposed for a short period. It was exposed again in in 1984 and September 2001.

That part of Fiona Beach was renamed Submarine Beach on 14 January 1977.

A team from the NSW Heritage Office led by Tim Smith undertook a search for the wreck using a magnetometer and located it below 3 metres of sand on 20 July 1999. Tim Smith reported again on 10 May 2000 that the wreckage had been partially exposed again confirming their magnetometer search findings from 1999.

On Friday 23 March 2001 at 12pm an interpretive plaque commemorating Dutch Submarine K IX was unveiled by the Deputy Premier of NSW, the Hon Dr Andrew Refshauge MP, at the Sugarloaf Point Lighthouse near Seal Rocks. Invited guests included the Consul General of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Netherlands Ex Servicemen & Women’s Association (Australia), the Naval Historical Society of Australia, and the Submarines Association of Australia. The plaque was mounted on the sea shore a few kilometres north of where the wreck lies.

In mid September 2001 the submarine wreckage was exposed again after some king tides in the area.