By Captain C.F. Gower, SAN (Rtd)

This interesting recollection of a first submarine command experience by Captain Goodwin Felton Gower of the South African Navy was provided by his son Allen Gower who lives in Sydney. Goodwin Gower was born in Durban, Natal, South Africa on the 20th May 1921 (less than a month before Prince Philip). He joined the South African Navy in 1938 and completed his initial training at the end of 1939 before posting to the RN college, Dartmouth in January 1942.

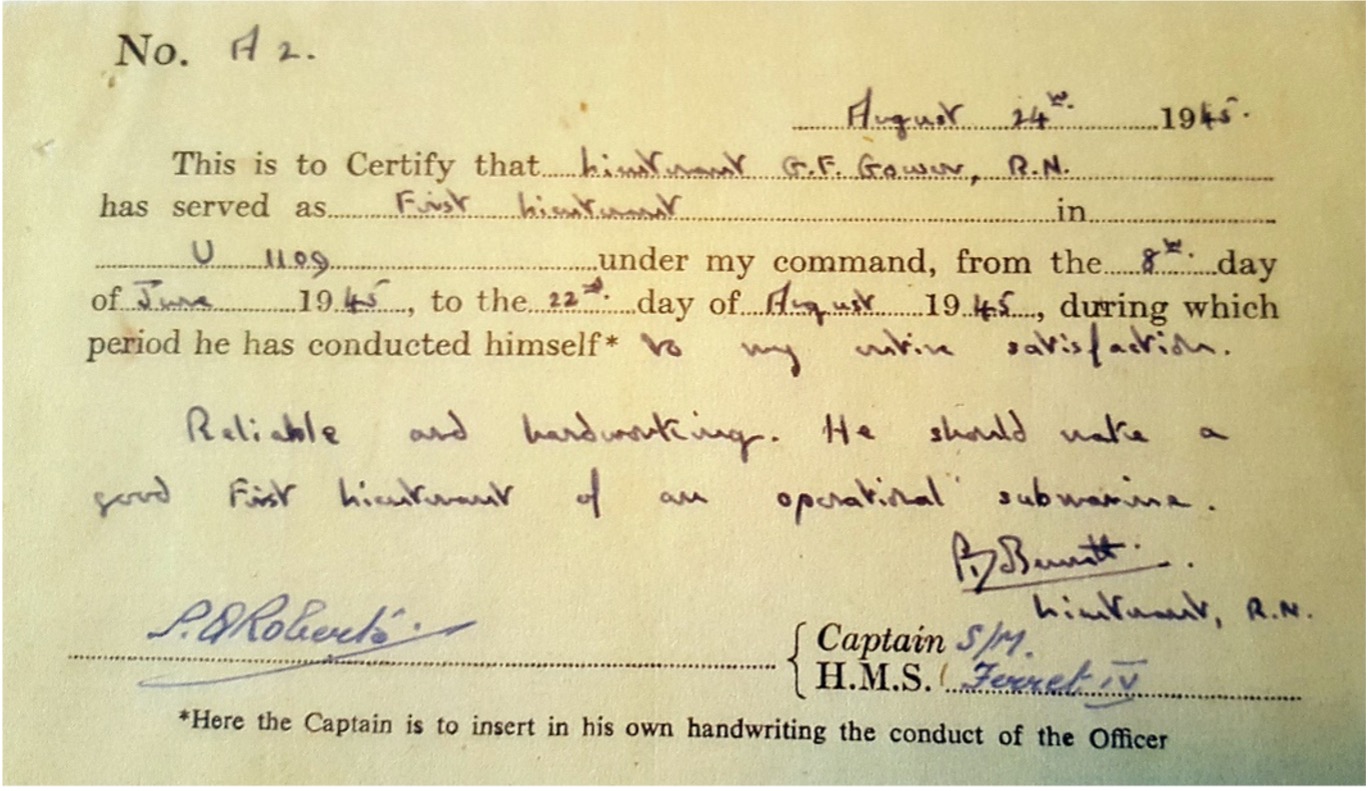

After sea time as a Midshipman in HMS Malaya he commenced submarine training in November 1942 in HMS Elfin and was promoted to Sub-Lieutenant on completion. After service in HMS Tactician in the Mediterranean, Malacca Straits and Ceylon he returned to the UK in June 1945 to receive surrendering U boats and operated U-1109 for short period. He continued service in the Royal Navy until January 1948 before returning to his family in Orange Free State, South Africa. After being a farmer for 7 years he re-joined the SA Navy in 1956 and retired in 1979. He died in Cape Town in 1993.

This story was first published in VLOOTNUUS/NAVY NEWS, VOL VII APRIL 1988

The greatest moment in a naval officer’s career is when he takes command of his first ship. My first command was a rather unusual one. I was stationed at Lisahally on Loch Foyle, Northern Ireland, where 85 German U-boats were under care and maintenance awaiting the decision of the Allied Commission as to what was to be done with them.

The boats were divided into groups of ten, each group under the care of one British and one German crew. At one stage the government decided to place several of these boats on show at various ports in the British Isles so that the public could see the vessels which very nearly led to their defeat.

I was detailed to take command of U 1109 and take her the 15-odd miles up the River Foyle to Londonderry. I had pointed out to the Captain SM that I had a crew but no experienced coxswain, and he assured me that both a coxswain and a pilot would be provided. The engine-room department was manned entirely by Germans and the upper-deck staff consisted of British submariners. Engine-room telegraph orders were given in German while helm orders were given in English.

When one wears the uniform of a naval lieutenant with two rows of campaign medals and stars, one cannot help but be brimful of confidence and pride. As we closed up harbour stations and I stood on the bridge waiting for departure time, I owned the whole world. But as yet neither the coxswain nor the pilot had arrived.

The steering arrangement on these U-boats consisted of a box attached to an electrical lead brought up from the control room and hooked on to a bracket on the bridge. On top of the box was a bar which was held in both hands and under each wrist was a knob which was depressed by moving the wrist downwards to turn to port or to starboard as required. Between the knobs was a dial indicating the number of degrees of rudder on at any time.

Soon I spied a short, stocky chief petty officer striding down the jetty, have a short consultation with a leading seaman who pointed in our direction, and before long CPO Herbert Evans DSM was on the bridge reporting for duty — all five foot seven of him with white hair showing under his cap and hair growing out of his ears and nostrils. “Welcome on board, Coxswain, will you take the wheel please?”. I said waving vaguely in the direction of the box. Evans looked all around the bridge and in some puzzlement said to the signalman, “Eve, where’s the bleedin’ wheel then?”

At this, I put my hand on the box and said, “This is the wheel coxswain”. Now many naval officers know the sort of look a senior rating can give when he wishes to convey something without reverting to words. My interpretation of Evans’ look was, “I wonder if he’s daft”. He adopted a crouching attitude and then gazed at the box as though he was expecting a jack-in-the-box to pop out. I then gave him a demonstration as to its working and watched him try it out with obvious distaste. After all, whoever heard of a ship without a wheel? After looking at it for a further few seconds his sole comment was, “Blimey!”

Next to appear on the jetty was a man in a dirty brown raincoat wearing a bowler hat. He had a few words with the leading seaman on the jetty who again pointed in our direction and in a few moments our pilot appeared on the bridge.

I saw fit to throw him a salute and said good morning to which he replied, “Morning laddie, and where’s the old man then?” I drew myself to my full height and informed him that I was in command, which caused him to clear his throat and say something which I could not understand. My pride was holding out quite well but my self-confidence was beginning to take a bit of a knock. I thought to myself, “Here I am a little outfie from Tweespruit in the Orange Free State, in command of a German submarine with a German engine-room staff requiring the telegraph orders to be given in German, a discontented and unhappy coxswain who had to have helm orders in English, a British upper-deck staff and an Irish pilot whom I could hardly understand.”

After explaining the situation to the pilot I suggested it would be best if I manoeuvred the vessel into midstream and then he could take over. As I looked over the side I could see a four-knot current running, and departure time was at hand.

“Beide E Maschinen!”

“Port twenty-five!”

“Let go all lines!”

“Steuerbord E Maschine! Kleine fahrt voraus!”

“Backbord E Maschine! Kleine fahrt zuruck!”

“Midships the wheel!” “Stop Steuerbordl” “Starboard fifteen!”

“Beide E Maschinen halber fahrt zuruck!”

“Midships the wheel!”

“Stop beide E Maschinen!” “Beide Diesel Maschinen!”

At this point I felt I was ready to qualify for the home for the insane, and was happy to say to the pilot he could take her now.

This gentleman startled the wits out of me by saying, “Full ahead the engines!” and almost on an automatic reflex I said to the telegraphs man “Beide Diesel Maschinen grosser fahrt voraus!”

A waft of black smoke came from both exhausts, accompanied by a deep rumbling sound from aft; the water around the stern boiled furiously as the stern dug down and we rapidly gathered speed. Those U-boats could manage 17,5 knots and soon we were doing all of that winding our way up the narrow river, the pilot giving unintelligible instructions to a very unhappy coxswain fiddling about with the un-familiar steering-box.

At one stage we heeled over as we turned sharply close round a starboard hand buoy. Some ten yards on the other side of the buoy were several seagulls. The gulls were not swimming, they were paddling on a sandbank.

I was sure we should be going more slowly but my pride was such that I did not wish to be thought a coward, so on we rushed leaving a high wash sweeping up the banks of the river.

It was with considerable relief that we entered Londonderry Harbour area and I felt justified in ordering “Kleiner fahrt voraus!”

After we were alongside, I needed a stiff drink to settle my nerves and contemplate the joys of command and how long one’s nerves could last.

Editor’s Note

Following the German surrender in 1945 operational U-boats were ordered to surface and sail for Allied ports. Most made for the UK. On 9 May 1945, the first of over 150 U-boats surrendered started to arrive. Over 200 more were scuttled. Of those surrendering, a quarter were taken over by the Allied powers and the rest sunk by the Royal Navy in the Atlantic off Northern Ireland in Operation ‘Deadlight’ through to January 1946. Further Reading