Discovery of propellers from the ship explains why Peary was the only warship of several vessels to be sunk

By Dr Tom Lewis[1]

This paper was previously published in The Arms Collectors Journal of the Northern Territory, and Warship magazine.

The discovery in Darwin Harbour of the propellers of the fighting destroyer USS Peary has rewritten the story of the biggest air raid on Australia soil, the attack of the Japanese Navy on 19 February 1942.

Located around two kilometres from the wreck site of the rest of the ship, and complete with their drive shafts, the propellers lie in a debris field which may yet reveal other items from the ship. But that the stern of the ship should have been forcefully separated from the rest of the vessel when she was subject to a ferocious dive bombing means the story of how the ship sank needs retelling.

The destroyer USS Peary was one of the largest warships in Darwin on 19 February 1942.[2] Her four funnels, known as “stacks”, made her instantly recognisable as a target for the Japanese. Indeed from a distance this class of destroyers were sometimes mistaken for Marblehead-class cruisers, which also had four funnels. All of the merchant ships, and the RAN warships, present in Darwin that morning had just a single funnel, so Peary was a stand-out. There was a sister-vessel present, the USS William B Preston, but she had been refitted as a seaplane tender, with two stacks. Peary was anchored a little under a mile from the main wharves, in the middle of the harbour, not far from the hospital ship Manunda and the troopship Zealandia. The other warships present were the RAN sloops Swan and Warrego, and the corvettes Deloraine and Katoomba; the latter in the Australian Navy’s floating dock. Altogether, there were 57 vessels in the harbour that morning. All of the warships except Peary survived – an interesting fact for which there have been a number of incomplete/unsatisfactory explanations. The discovery of the propellers finally fits the puzzle together.[3]

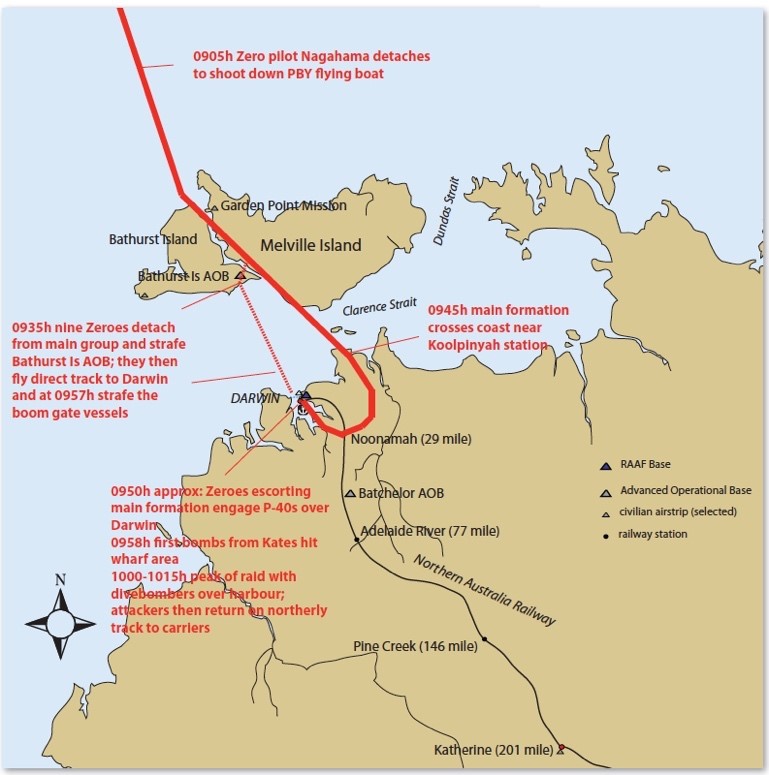

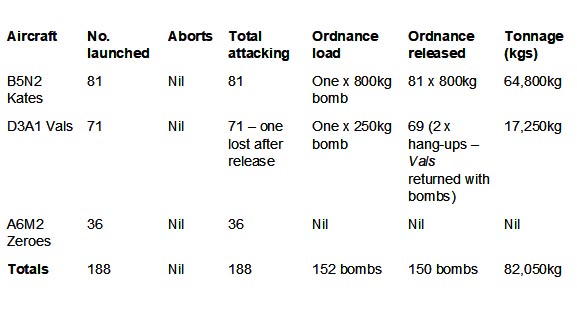

On the 19th of February 1942 Darwin was struck by a massive air raid at nearly 10 in the morning. 188 aircraft from four aircraft carriers, in a 17 vessel battle group, hit the town and harbour with high level bombing from Kate three-man bombers, and Val two-man dive bombers, all escorted by Zero fighters, which demolished the resistance from a mere 10 P-40 Kittyhawk fighters of the United States Army Air Force. Eleven ships were sunk, 30 aircraft destroyed, and 236 people died. The Imperial Japanese Navy lost four aircraft and two aircrew.

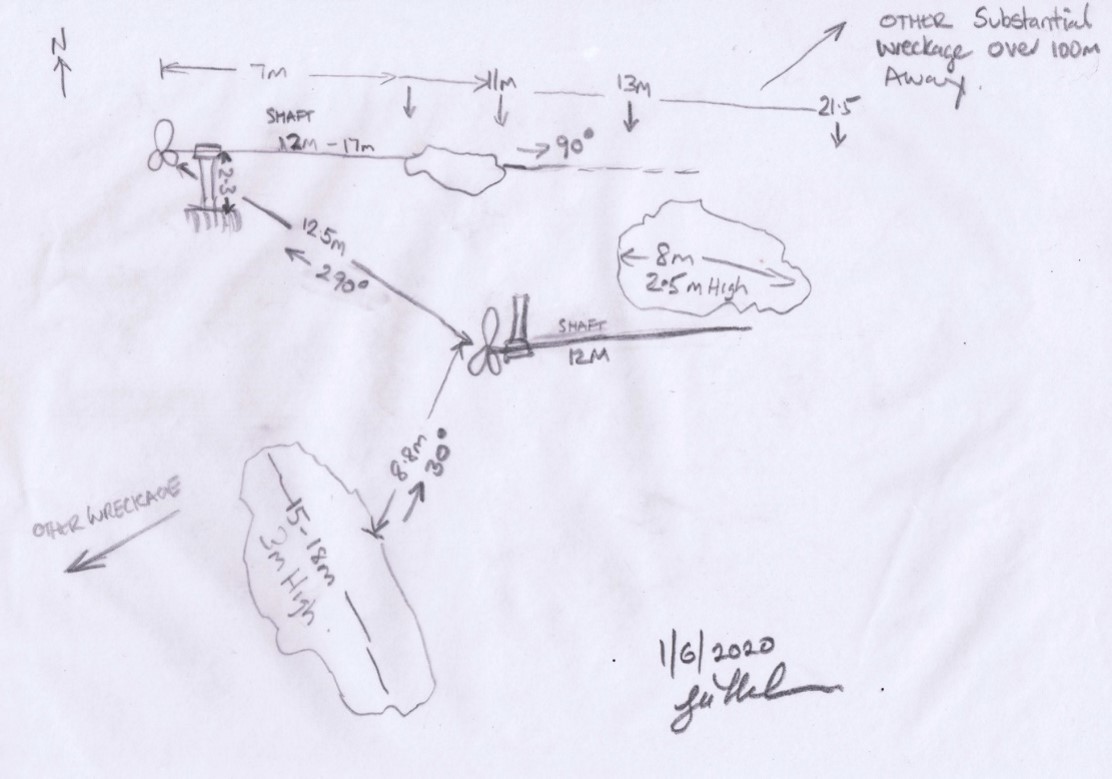

This massive raid has been described in detail several times; with the most comprehensive account in Carrier Attack, by this author and Peter Ingman. What has changed the Peary story is the discovery on 15 May 2020 of two propellers on the seabed of the harbour. Discovered, and then subsequently explored in some detail, the fascinating find was made by Grant Treloar, Roland Hugli, and Clive Bartsch, all local scuba divers. They were searching for the lost Sunderland aircraft Corinthian. The propellers, with one blade upright and two within the seabed, had shafts and struts attached. In Grant’s words, “There was lots of wreckage, all much smashed up, very difficult to recognise. It looked like a catastrophic event had happened. The wreckage is scattered over 200 metre debris field, but we found one large piece 118m away.”[4]

So what happened on the day of the action, when Peary was sent to her death, along with 88 members of her ship’s company, by the aircraft of the Japanese Navy?

The Peary was a 22 year old destroyer, carrying four funnels which gave her a very dated look. In her original measurements she displaced 1,190 tons and was 314 feet in length. She was armed with four 4-inch low-angle guns; one 3-inch AA gun (nominally – see later notes), and eight machineguns. She also carried twelve 21-inch torpedo tubes in four triple mounts. Launched in 1920 and named after the famous Arctic explorer Robert E. Peary, the destroyer was serving in the Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines when the Pacific War began. She seemed to have had more than her share of bad luck. Before the Darwin visit she was hit by a bomb in the Philippines which killed eight of her crew, then attacked by three Australian Lockheed Hudsons which mistook her for a Japanese ship.

The Peary was a 22 year old destroyer, carrying four funnels which gave her a very dated look. In her original measurements she displaced 1,190 tons and was 314 feet in length. She was armed with four 4-inch low-angle guns; one 3-inch AA gun (nominally – see later notes), and eight machineguns. She also carried twelve 21-inch torpedo tubes in four triple mounts. Launched in 1920 and named after the famous Arctic explorer Robert E. Peary, the destroyer was serving in the Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines when the Pacific War began. She seemed to have had more than her share of bad luck. Before the Darwin visit she was hit by a bomb in the Philippines which killed eight of her crew, then attacked by three Australian Lockheed Hudsons which mistook her for a Japanese ship.

After escorting the USS Langley to the West Australian coast, Peary sped back to Darwin to take part in the Timor Convoy venture. On the night of 18 February she left port again in company with the cruiser USS Houston but was detached to aid the corvette HMASTownsville in a submarine search just outside the harbour. The search was unsuccessful, but so much fuel was burned up that she needed to return to harbour for fuel. She anchored in berth F-3 at about 1am, early in the morning of 19 February.[5]

The records of the Peary, and the exact description of her last movements, as given by her command team of officers, are not known, as the captain, Lieutenant Commander John Mark Bermingham USN, died with the ship, as did all of the officers aboard except Lieutenant RL Johnson, USNR. Her final action was officially described by one of her officers, Lieutenant WJ Catlett USN, in a report of 6 March 1942 to the Secretary of the Navy.[6] Catlett was not on board for the action however; being temporarily detached for medical treatment. He interviewed witnesses from Peary, USS William B Preston, USAT Meigs, and HMA Hospital Ship Manunda. His report reads:

At about 1045, the U.S.S. Peary was attacked by single motored Japanese dive-bombers. The first bomb exploded either on the fantail or very close thereto, removing both propeller guards, depth charge racks and flooding the steering motor room. The second bomb landed on the galley deck house and was an incendiary bomb. The third bomb pierced the main deck and went through the hull of number two (steaming) fireroom. It did not explode. The fourth bomb hit forward and set off the forward ammunition magazines. The fifth bomb, an incendiary, exploded in the after engine room. The U.S.S. Peary sank, stern first, at about 1300, February 19, 1942. [7]

Like most of the ships present, the first indication that Peary would have had of an enemy raid was the high level Kate bombers being directly overhead, and bombs falling in the near vicinity. Like all warships present in Darwin that morning, steam pressure was maintained so the ships could get underway at short notice. Anchored, the four-funnel destroyer would be an easy target, but the ship still had steam up. LCDR Bermingham would have given orders to raise anchor so he could head for searoom and present the attacking aircraft with a moving target. But raising the chain and anchor slowed down his actions, and the ship was a slow-moving target.

Why did Peary not merely slip[8] her anchor and chain for a quicker getaway? According to Dallas Widick, an anchor-party survivor who later visited Darwin, the anchor probably was never fully recovered. Instead, he related, chain was taken in but the anchor was never off the bottom. Mel Duke, who was the Peary‘s bosun’s mate, thinks that the anchor was “short-stayed” – just resting on the seabed – and the ship lifted it enough to allow the ship some movement, although the drag and weight would have been immediately noticeable to Bermingham and the bridge team.[9] Normally a captain would not start manoeuvring until certain that the anchor was clear of the seabed, with the anchor being “sighted”. Under the extreme danger facing Peary on that day, it is possible that the captain chose to start moving as soon as he believed the anchor was off the bottom, or very close to it. But he would continue to heave the anchor clear of the water surface as quickly as he possibly could, even as he was making way.

It was likely the destroyer had only one anchor, and that was holding her to the seabed. To let it go and have no anchor at all would have been dangerous: anchors are essential equipment; it’s an oft-quoted maxim at sea, generally after something has gone wrong, that ships don’t have handbrakes as cars do. You need an anchor to stay in one place, especially in big tidal areas such as Darwin, with tidal flows of up to seven yards or metres in six hours. If you get into a situation where you lose engine power it’s the only way of not running aground in an emergency – that is if the water is not too deep. Having an anchor also allows you to kedge if you run aground: moving the anchor to another place then dragging the ship towards it, although you need two for really efficient warping. If you have no anchor that is to place the ship in a most serious situation. No captain will lose one if they can possibly avoid it.

Bermingham had no way of knowing what he was up against in the raid. Peary had survived level-bombing attacks in the Timor Sea. There she had the protection of Houston’s guns; now her skipper probably reasoned they had protection of the Darwin area guns. Probably the last thing he expected were swarms of low level dive bombers. If he only had one anchor on the foredeck – the other buoyed somewhere or they’d lost it – then he would take the extra minute to raise his last anchor, rather than slip the pin and lose it entirely. Buoying it would take just as much time or even more. The buoy wasn’t routinely carried on the foredeck: it was large and light, prone to wind forces as well as getting in the way of the foredeck party. So the anchor was probably hoisted, and merely short-stayed, and Peary lost vital seconds.[10]

What is generally agreed is that the ship’s guns engaged the Japanese aircraft, but Peary had no really effective anti-aircraft armament. Her four low-angle 4-inch guns were suitable only against surface targets although they would likely have been fired at any possible low-flying aircraft. For AA protection the destroyer had four 0.30 calibre machineguns on the after deck house, and four 0.50 calibre machineguns on the galley deck house. [11] She was originally equipped with one – some accounts say two – short-barrelled 3-inch AA gun on the aft deck, but it seems clear this had been removed. There is no mention of it being used in air engagements in USN records. For example, in an action against three Hudson bombers which mistook her for enemy the Peary report described “The .50 and .30 caliber machine guns of the PEARY were kept firing during each attack.”[12]

Peary was the only warship sunk in the action, and this has always been a bit of a mystery. The two RAN sloops Swan and Warrego – armed with high-angle four inch guns rather than the low-angle model on the Peary, plus either quad Vickers machineguns or a formidable array of the excellent 20mm Oerlikon – put up a good defence, and the smaller corvettes too, although Deloraine could not move as she was having her boilers cleaned.[13]The ships that were sunk were all relatively unarmed: tankers British Motorist and Karalee; freighters Neptuna, Mauna Loa, Meigs and Zealandia; lugger HMAS Mavie, and coal hulk Kelat, and several small launches and working vessels. Why a heavily armed destroyer would be sunk is strange considering her fellow warships survived. But as will be seen, Peary was not only anchored, but was crippled: her entire stern was blasted away.

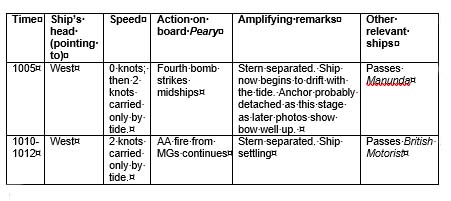

The timing of Peary’s last movements

In this analysis, we are interested in the precise details of Peary’s last moments, for this can lead to how accurate we can be in assessing whether the propellers belong to the destroyer. The accounts given below have been arranged from the briefest duration afloat to the longest; accounts which do not specify a time are given last.

- Preston’s Officer of the Deck, Lieutenant Wood said that they were about 300 yards from the Peary when it was hit: “…the Peary was struck and immediately burst into a complete envelope of flames and sunk shortly thereafter.”[14]

- Lieutenant Herb Kriloff of the Preston said: “USS Peary was now abeam to starboard, perhaps three to four hundred yards distant. The both of us made fine targets. Two groups of fighters and dive bombers now launched a co-ordinated attack. We were to port, and just forward of Peary, starting to pull further ahead, when we were both strafed and bombed. In seconds, Peary was enveloped in a ball of flame. She continued detonating until disappearing from view. The explosion was blindingly bright, and when you opened your eyes, it took time to adjust.”[15]

- Len Gable saw Peary subjected to very heavy bombing and then sinking quickly with water awash on her weather deck and guns firing. He thought she then was suddenly enveloped in flames and then sank fast.[16]

- Gunner Jack Mulholland, up in the cliffs only some hundreds of yards away, thought her sinking happened “within 10 minutes” of the raid commencement.[17]

- Pat Forster, sighting Peary “only 300 metres away from us” related that “she sank into the flames, disappearing without trace within fifteen minutes”, and later thought that “the USS Peary was sunk first; I saw the bow sticking out of the water.” [18] [19]

- Able Seaman George Ireland on board HMAS Platypus said: “We tried to cover Peary as best we could, but we couldn’t….we watched the dive bombers come in one in after another. And the first hit amidships, and then she got one on the bridge, and then she broke in two. The for’d gun was still firing…”[20]

- Dallis (sic) Widick: “The ship went to battle stations, but we were at anchor, which had to be raised. That was part of my job. The front of the ship was coming out of the water. All of the officers onboard were dead, so the chief boatswain’s mate gave the order to abandon ship. We all jumped over the side.”[21]

- Stoker Frank Marsh who was on the Deloraine nearby, says the Peary was anchored not far from his own ship, and was “hit early”, being quickly set on fire. “It definitely moved around in a semicircle but was moving astern.” [22]

- Peary crewmember Mel Duke remembered: “Then the divebombers came in. We tried to get under way, but we got one hit amidships, then a couple in the after section, and she caught on fire…”[23]

- Able Seaman Harry Dale on board Karangi said that “Peary who is only a few hundred yards away from us is putting up plenty of flack and machinegun fire…there are five divebombers they seem to be hidden in the cloud, they are dropping everything at her.“[24]

- George Boniface, 5th Engineer of the Neptuna, recalled: “The destroyer U.S.S. Peary was on fire and sinking although we could see the flash of her guns still firing; an oil tanker was on fire while smoke from the Barossa, plus the smoke from the Neptuna explosion, blanketed the harbour.”[25]

- The captain of HMAS Southern Cross, Lieutenant Commander Symonds, reported Peary sinking fast as the very first part of the harbour action he saw: “The examination vessel HMAS Southern Cross, an unarmed ship except for two rifles, slipped from the buoy [600 yards from Darwin’s main jetty] as the first bombs fell on Main jetty, [all] hands at stations for air attack and proceeded at full speed away from the vicinity of Jetty. The US destroyer Peary was seen on the Port side fiercely ablaze from stem to stern, sinking and with two men already in the water.”[26]

Conclusion as to the timing of the sinking

It is notable that all of those who place a timing on the sinking have it within 15 minutes from the raid start at 0958[27] as a maximum. How Lieutenant Catlett arrived at 1300 hours (1pm) is not known. In fact the whole report of Peary’s sinking within the US Navy is extremely short on detail: dated 6 March 1942, two weeks after the sinking, it covers only two pages, but the ship’s movements and combat actions in the two months beforehand cover scores of pages.

Frustratingly, Catlett did not name the witnesses he spoke to. How the witnesses from the Preston were interviewed is not known: she left harbour later that morning; proceeded down the west coast of Australia, and finally ended up many weeks later in Sydney for repairs, after trying without avail to have the ship’s extreme damage – the stern nearly fell off – fixed in other ports. Preston’s people could have given some indication of Peary’s sinking to Catlett by radio Morse code, but there is no indication of this in first hand accounts such as Lieutenant Kriloff’s extremely detailed book which recounts Preston’s adventures day by day for several months afterwards.[28]

Who and what sank the ship? (See explanatory footnote [29])

- Peary crewmember Dallas Widick said: “The first bomb was aft…the third bomb hit the bridge.”[30] However in a newspaper interview he said the Peary “took five hits, from the stern – rear – to the bridge. The fifth and final hit struck the magazine. The ship exploded.”[31]

- Peary crewmember Laurence T. Farley was thrown into the sea by one explosion and burnt, dived overboard, to be recovered by the Manunda. However the headline of the article carrying his interview stating five hits was not borne out by his comments. [32]

- Peary crewmember Mel Duke on board the Peary was in ‘the well deck between the bridge and the galley deck” when “the first bomb hit aft.” Within “seconds” one more hit the bridge and another the galley deck house”.[33] He said the galley roof machineguns definitely engaged.[34]

- Duke in another interview thought that the ship was “hit five times from the stern up to the bridge, and the one that hit the bridge went in down to the forward magazine and the forward magazine exploded, and I believe at that time it broke the ship in two:”[35]

- A somewhat melodramatic report in the Washington Evening Star reported four bombs hit the ship, and a fifth near-missed near the bridge.[36]

- Gunner Mulholland, on the clifftops above the harbour, with a task of spotting enemy aircraft for his AA gun to target, was in an excellent position to see the harbour fight. He thought Peary was hit by the divebombers.[37] In his book Darwin Bombed he said Peary “did not appear to be moving or taking evasive action and was hit several times.”

- The Japanese report, which goes into extensive detail about what targets they hit, is specific about ship type. “A unit of Val carrier-based bombers from Sôryû (led by Lieutenant-Commander Egusa Takashige) – The 1st Company (nine carrier-based bombers): “Sank one destroyer on fire, set one destroyer on fire, set one medium-sized merchant ship on fire, and set a heavy oil tank on fire; our side received no damage.””[38]

- George Haritos said: “I saw the Peary get hit, and I saw the British Motorist cop one practically down the funnel, or it looked like it from over there – she was an oil tanker. The Peary was an American destroyer, and it was going down and still firing the for’ard guns.”[39]

- Able Seaman Harry Dale on board Karangi noted after seeing the Peary hit repeatedly that “the ships along side the wharf have just blown up…we have ducked for cover, shrapnel is falling everywhere.” [40] AB Dale had seen the US destroyer firing and then recalled “the Peary has just been hit again, she is on fire, she never managed to get up any speed.” Later he recorded: “she’s sinking stern first nearly under now, the forward turret is still firing…” [41]

- Frank Marsh recalled: “…there were several explosions aboard Peary but not a final big sinking. It sank nearer to the hospital ship Manunda…It went down stern first.”[42]

- Pat Forster said: “The Peary…slowly slid stern first into a huge oil slick which had already caught alight.”[43]

- Machinegunner Bill Chipman was in action on HMAS Kangaroo, a boom defence vessel, near the Peary. He saw the ship dive-bombed – in fact he engaged the Val to no effect – “then after the loud explosion on the Peary we saw some of the crew on the forward deck; the after part of the ship was under water, and the chaps on the forward deck were still firing their guns as she drifted away, and eventually she went completely under.”[44]

- Chief Officer Minto on the bridge of hospital ship Manunda, 10 minutes after the first bomb, noted: “Another American destroyer was on our port side, a solid mass of flame with burning oil all round her and what was left of the crew jumping into the burning oil.”[45]

- Don Clegg, on board the Australian corvette Warrnambool, recalls: “the nearest ship was the Peary which was an American four-stacker destroyer and it was hit, and I must say I had a lot of time for the American sailors, when you see these fellows still manning their anti-aircraft guns with their ankles under water…”[46]

- Bill Eacott was at the Esplanade “overlooking the jetty, and saw the ships burning. It has been said that the Peary went down with its guns blazing, but I don‘t know that can be so, because there was nothing to blaze away at when I saw it going down. The Japanese had gone.” [47]

The Peary story of guns firing until the last is logically true enough if one accepts that the battle was over for her in 10-12 minutes. The sinking was so quick that there was probably no abandon ship order given, and her gunners would necessarily have stayed at their posts. But it is difficult to get a fully accurate picture; she certainly did not fight for long, and accounts such as a Wikipedia entry for October 2012[48] saying she fought until 1pm – probably derived from Catlett – are ridiculous. No-one except Catlett, who wasn’t there, says that.

Who and what sank the ship?

Peary was hit by several aircraft bombs, dropped from the Vals. Crewmembers Duke, Widick; the commander of nine Vals Lieutenant Commander Takashige, and Bill Chipman all specified dive bombers. It was not hit by one of the 800kg bombs carried by the Kates, but rather several of the 250kg bombs carried by the dive bombers.

It is indeed logical to conclude the Vals hit the destroyer, rather than the Kates. The bigger bombers’ attack run took them in a straight line over town and harbour, and indeed the left flank of the flights may well have sunk the US transports Mauna Loa and Meigs. But an 800kg bomb hitting a much smaller ship such as the Peary would likely have resulted in her wholesale destruction, although admittedly a near miss would have caused less damage. Two witnesses, both on the bridge of the USS William B Preston, Lieutenant Herb Kriloff and Lieutenant Wood, the Officer of the Deck, thought there was one explosion which sunk the ship, but four witnesses thought several divebombers inflicted the damage; two witnesses – Dale and March – said there were respectively two and “several” hits. (The very big explosion might have been the destroyer’s stern-placed depth charges detonating.) The Kate overflight was through in a few minutes, with 9 x 9 aircraft flights from the south-east taking place at the beginning of the raid. It was after the Kate release the 71 Vals moved in to attack targets of opportunity; the smaller aircraft could not strike before that as they would have been underneath the falling ordnance of the higher aircraft.

How many Peary people died?

The Killed In Action number for Peary has been the subject of much change over the years since the sinking. The original figure given in many histories is 80 or 81 sailors killed in the action. However, around the time of the 1992 commemoration of the Darwin raids it was revised by survivor Dallas Widick, who after finding his own name on a memorial plaque, set the number at 91. He counted those of the crew who survived the sinking and said that 91 died – a substantial amount of the total of 236 people lost in the Darwin attack. Given further revision through the highly researched Northern Territory Roll of Honour website, operated by the NT Library, it now stands at 88.[49]

Incidentally the fatality count of United States citizens and men contracted by the country – for example, the crews of the freighters Don Isidro and Florence D, both sunk in the afternoon off the Tiwi Islands – was higher than those from Australia. One hundred and twenty-eight out of 236 who died were from the USA.[50]

Finding the wreck

Efforts through the war and immediately afterwards failed to locate the wreck of the destroyer. The author of Darwin Drama, Owen Griffiths, writing in 1943, commented that “although a party from the ship later dragged for her systematically the only relic recovered was a part of one of the hawsers.” A USA Graves Registration Service unit also spent a week endeavouring to locate the ship in 1948, but to no avail.[51]

Some of the efforts to find the sunken destroyer may have been motivated by popular reports that the Peary contained a “fortune in gold bullion” when she sank. Douglas Lockwood’s book Australia’s Pearl Harbour, Darwin 1942 suggested that Peary took the gold aboard before sailing from the Philippines.[52] Various other contemporary sources also reported the story. The tale still circulated even after the salvaging of much of the destroyer. As late as 1970, a Neville Harding of Sydney “… and his diving team” were reported by the West Australian Department of Shipping & Transport to be coming to Darwin to attempt the search for bullion. A 1975 edition of the Victorian RSL magazine Mufti reported of the Peary “… with her wreckage to the Harbour bottom went a fortune in Dutch bullion”. The question had been resolved 18 years previously however when the Director of Naval History for the USN wrote to a Mrs Palermo, whose son had died in the action. He advised that (by-then) Captain Catlett had reported, in answer to the question, the destroyer had indeed transported gold bullion across Manilla Bay, on 26 Dec 1941, for the Philippines Government into General MacArthur’s fortress of Corregidor. However, Catlett had personally supervised the transfer of the gold ashore.[53]

As the war ended Darwin moved back to being a working port. Several of the wrecked ships were visible at low tide, and one – the Neptuna – lay on her side near the main wharf. It would appear that as part of an effort to clear the harbour some of the wrecks were sold, but the exact details of the sale has not been fully investigated here.[54] Peary was finally found in 1956 by the naval vessel HMASQuadrant, which passed across the top of the wreck by accident, but with suitable equipment functioning and alert watchkeepers. After Peary was located she was officially declared not to be a hazard to navigation. But the wreck did lie in the port’s quarantine area where it was considered by the harbourmaster to be a possible hazard to anchoring vessels. This may have been a factor in Peary‘s eventual disposal in 1960 to – ironically – a Japanese company, Fujita Salvage, who contracted to remove most of the harbour wrecks when two Australian companies failed to arrive as tendered.

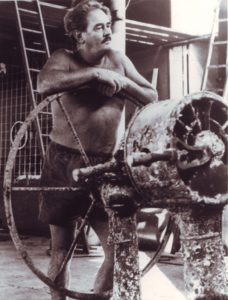

The salvage process was probably started in the 1950s by Carl Atkinson, a commercial diver who maintained a workshop in Doctor’s Gully, only a little way from the wreck site. Atkinson was an entrepreneurial diver. He bought some of the harbour wrecks, and landed parts of their cargo.[55] Deccaville tracking – the metal mesh used by the Allies to lay down airstrips in the jungle – tools, salvageable metal; all were recovered by Atkinson and often sold. He landed the Peary’s binnacle and wheel and at least one of her guns, although it is doubtful he actually owned the wreck: a letter from the USN to a crewmember’s parent disputes that he did.[56]

The US Navy was concerned about the disturbance of any human remains of their sailors who had died with the ship, and the return[57]of any cipher equipment. After some negotiation through the Australian federal government, it was agreed that if the ship was searched for human remains, and any found were recovered, then salvage would be acceptable.

Peary’s final resting place, in a 30 metre deep hole almost directly out from what was originally the Novatel Atrium Hotel on Darwin’s Esplanade, is some kilometres from her supposed[58] original anchorage, which would account for the US Graves Registration Service’s fruitless attempt to locate her. It was there over the top of the wreck that divers from the RAN anchored in 1959, and commenced their search, which lasted several days. Bill Fitzgerald, a Royal Australian Navy ex-diver, recalls that the diving was almost all completely carried out in zero-visibility conditions, with the searches conducted by feel.[59] They dived at slack water to clear the torpedo impact pistols and other material. The team was tasked with recovering the warheads from the torpedoes, but these had so much salt-water damage they had disintegrated. There were 12 torpedo tubes present minus one which, Bill recalled, Carl Atkinson had taken to make into a recompression chamber. The team took the propellers off the torpedoes and mounted them on a polished board and “gave them to the RSL for beer”.[60]

Bill thought the Peary had five hits from bombs – there had been explosions near the ship’s magazines, and big holes had been blown through the hull in places. They removed the remains of “quite a few” of the deceased for the US Navy.

Asked about the propellers, Bill said he had the impression “some of it” was there. The destroyer was vertical; only listing a little to the starboard side. The divers swam into the after end of the ship through the ship’s hull on both sides. He did not notice whether the props were present as the bottom of the hull was “well into the mud”, and it was very hard to dive because of tides and mud. It was “pitch black” on many penetrations and the divers navigated by feeling their way around.

Following the RAN dives, Fujita Salvage cut away the top hull and deck steel of the wreck, finishing their operations in early 1961. The wreck site today does not resemble the remains of a ship at all.[61] The destroyer’s keel sections are thought by local divers to remain under the seabed, with the rest of the site consisting of various loose items such as ladders, pieces of piping, and pieces of largely unidentifiable metal. Empty brass shell cases of the Peary’s bigger guns, showing they were fired in the action, have often been found on the site, as have various smaller artefacts.

In 1992, one[62] of the four-inch guns, either the forward weapon, or one of the two midship guns, recovered from Carol Atkinson, was mounted on the Esplanade, pointing out to sea to the spot where the Peary‘s wreck remains lie, for 50th anniversary commemoration ceremonies. On the seaward side of the gun is a plate presented by former crewmember Dallas Widick, displaying his revised list of the 91 crew lost. The captain of the USSRobert E. Peary, an American Knox-class destroyer – the descendent of the WWII ship, albeit with a slightly changed name – present for the 1992 commemoration, was presented with a brass shell casing and the original wardroom keys, recovered from the wreck by local scuba divers Warren Allen and Phil Franklin.

In 2008, Dallis Widick, passed away. His family travelled to Darwin from the United States to scatter his ashes over the shipwreck. “That’s exactly what my husband wanted. He wanted to be buried with his friends in Darwin,” his widow, Lorna Widick, told local news.[63]

In 2009 the last surviving member of USS Peary, Petty Officer 3rd Class Ben Mac Greer born in 1919 died aged 90.

What does the find of stern sections of the ship add to the story? The three divers contacted the Heritage Department of the Northern Territory, who began extensive investigations into the possibilities, driven primarily by their responsibility to safeguard items of historical significance.

One of the primary questions was whether separation of the wreck into two sites was possible. The immediate answer was yes, for this has happened in many sinkings, of both warships and civilian vessels. Perhaps the most famous is the Titanic disaster of 1912. The liner gradually settled by the bows after her collision with an iceberg, and in her final plunge to the seabed broke in half. The bow of the warship HMAS Sydney broke away in her last combat action.[64] This confirms the German account of her being torpedoed during her 1941 fight with the German raider Kormoran. The destroyer USS Abner Read hit an enemy mine on 18 August, 1943. The stern and a five inch gun were detached in the ensuing explosion, although the rest of the ship remained afloat.[65] About 35 feet of the German battleship Bismarck’s stern became detached and fell off in her final battle against the Royal Navy in 1941. She was struck in the stern by one air-launched torpedo, and then later in a gun battle by numerous shell strikes before turning turtle.

Internal explosions can account for severe structural damage resulting in sections becoming detached. The Japanese battleship Musashi, with her sister-ship Yamato the most heavily armed battleships ever built, likely suffered an explosion from a magazine which resulted in her stern becoming separated; it now rests at the wreck site upside down.[66] The same cause – battle damage resulting in a magazine explosion – caused the loss of HMS Hood in World War II. (Differentiating between external blast and internal, and the attendant damage of structural failure falls within a scientific analysis known as Battle Damage Assessment.)

However, such massive destruction as the stern of a warship becoming detached generally receives an incredulous reaction from people unused to ships. Some of this seems to reflect a thinking that ships are entire pieces of steel, rather in fact being a series of compartments, usually held together by riveting or welding. These fasteners can break if sufficient force is used. The sides or the horizontal surfaces of the compartments can be ruptured by impact, whether from natural obstacles such as rocks, or by man-made means such as gun shells or missiles. Indeed, guns for the last few centuries have featured different types of shells: some “armour-piercing” being solid steel “slugs” propelled by the explosive charge set off in the gun; or explosive, designed to cause damage once inside the target.

The type of bombs employed by the Val dive bombers which targeted Peary were “Type 99, No. 25” weapons used widely against sea targets. They contained containing approximately 133 pounds of trinitroanisol.[67] This is an explosive with a detonation velocity of 7,200 meters per second, therefore making it a high explosive, with a wave front moving faster than sound. Trinitroanisol was a stable composite similar to TNT (trinitrotoluene) an excellent, inexpensive explosive. It was therefore suitable for life as sea, and fairly rough handling, being subject to the forces generated on a moving ship, and comparable shocks beneath an aircraft.

The high weight of the bomb at 250 kg, with only 60 kg of explosive inside the casing, provided penetration of the hull by the bomb when it met initial decking. To operate effectively the Type 99 No 25 had a tail fuse and so it generally detonated below the upper deck of the ship so the blast effect was further enhanced by being constrained below deck.

The damage caused by such weapons would be devastating in an open air blast without obstacles: it would cause blast damage due to over-pressure at 50 ft (16 m) of 17 psi, and at 100 ft (31 m) of 5 psi. Penetration of steel armour plate of up to 32 mm thickness would occur, as would penetration of concrete of up to 518 mm.[68] People standing around 100m away from such a blast in the open would have been killed.

These bombs would have been sufficient to have caused massive damage to an unarmoured ship such as a destroyer if a weapon struck the weather deck centrally. Several bombs striking directly would have caused even more, and if they were striking the same spot their effect would have been a tearing action for the plates making up the stern hull. We cannot know exactly what happened, due to the wreck being partly salvaged. But it would appear the extremely heavy propellers became separated from the rest of the ship, perhaps due to the collapse of the surrounding hull.

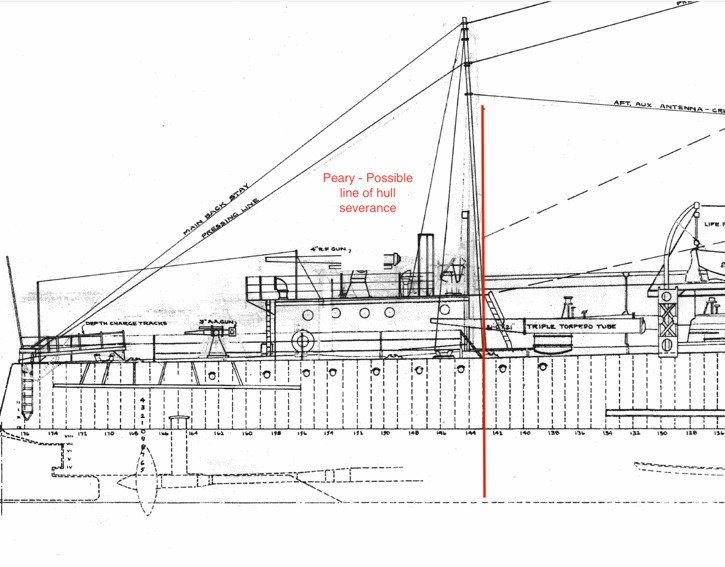

The newly discovered wreck site has two propellers which are still attached to their shafts, both with their brace to the hull attached, one of 12.5m in length attached to a five metres metal mass, and one of 12 metres. Whether the entire stern was severed from the end of the ship to 17 metres forward, or even more, is unknown. Peary was made up of 176 vertical frames, with roughly one every .5 of a metre.[69] This shows us that the longest propeller shaft takes us to frame 143. Therefore roughly one-fifth of the overall length of 96 metres, or 17%, became detached.

The propellers and braces match photos of the Clemson class screws, although no exact size has been found from blueprints and plans. There are no other war or cyclone damaged ships of the same size which could have been the source.[70]

There are many objects in the debris field near the propellers. They include:

- A circular item, perhaps the base plate of a 3-inch AA gun mount, of 1.3 metres across. This is likely the deck plate of the landed 3-inch gun. The plate is too small to be one of the four-inch mounts. There was one aft four-inch gun on the Clemson class. That gun, weighing 2.725 short tons, would likely be buried in the seabed.[71]

- A possible mast, or a boom, of approximately eight metres. The Clemson class destroyers carried a mizzen mast.

- Several large metallic masses, perhaps part of the ship’s superstructure, including one of eight metres in length 2.5 high, and another 15-18m three metres high. These could be the turbines of the ship.

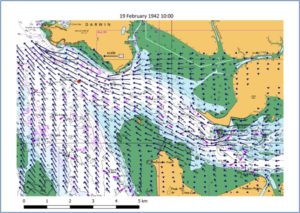

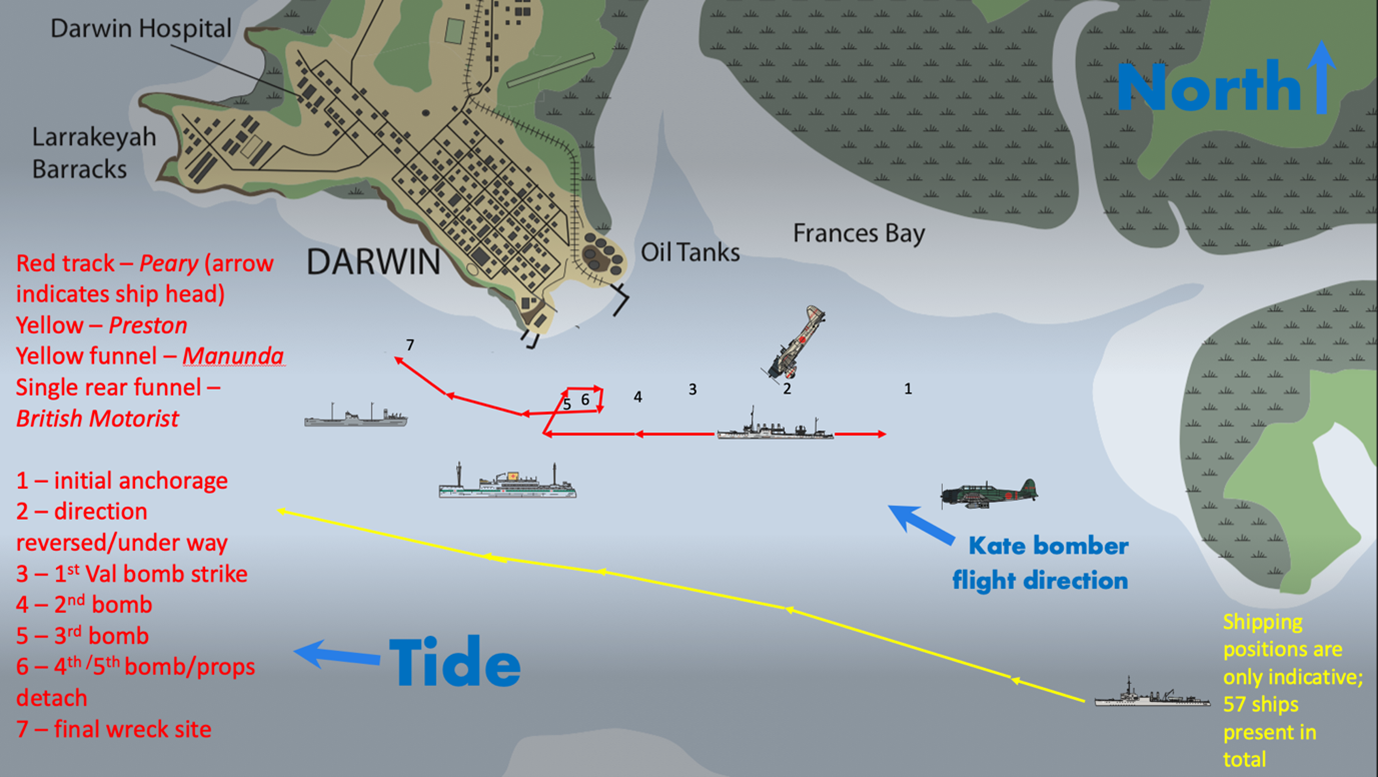

Of interest is that the propellers and shafts are lying on a west-east axis, with the screws themselves to the west. The tide on 19 February at 1000 was going out, with high tide at 0730 (6.607 metres), and the next low tide at 1400 (0.280). In Darwin Harbour on that day (see chart below) the tide was running from the east to the west.[72] When the propellers became detached, their extreme weight of several tonnes each would have meant they would have descended immediately at speed to the seabed only tens of metres below. They would not have had time, nor was the tidal movement been strong enough to turn them around. However, the tidal movement of nearly six metres, pushing many thousands of tonnes of water outwards, would have been enough to carry the sinking destroyer to its eventual location.

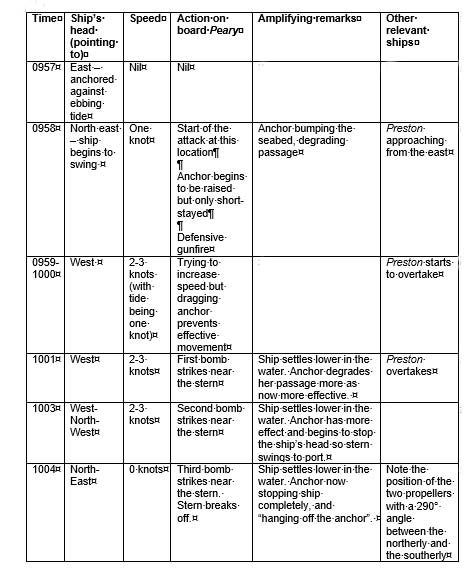

One problem with this is that Lieutenant Kriloff’s account of the sinking has Peary and Preston both with their ships’ heads pointing in the same direction: roughly to the west. How therefore could the bows of the Peary be pointing to the east? Here is a step by step analysis of what may have happened.

The debris field around the propellers suggest much of the stern hull steel went with them. The fact that the drive shafts connected to the propellers are pointing to the east is significant. It suggests that the ship’s bow was pointing east when the propellers and shafts, along with other parts of the stern, became detached. But east is the last direction Lieutenant Commander Bermingham would have chosen: the main imperative for a warship captain under attack would have been to obtain maximum sea room so he could manoeuvre at high speed, and in Darwin Harbour that lay to the north and west. As the table above shows, it was likely there was a temporary check due to the anchor becoming more effective. Being completely stationary likely enabled the fourth or fifth strike on the ship, which most accounts say happened midships. This likely detached the anchor, enabling the destroyer to drift away. Once again the lack of manoeuvrability was Peary’s downfall.

Being attacked by aircraft in WWII took a cool head to manage. One of the best fighting commanders of the Royal Australian Navy was “Hec” Waller. In battles in the Mediterranean in the early part of the war he showed great courage under enemy attack, waiting for the bombs to detach from the aircraft, and calculating how best to manoeuvre the ship.

The cooks & stewards nicknamed Waller “Hard Over Hec” as most of his wheel orders, in action, were ‘Hard a Stbd or Hard a Port”. Waller would lay back in his chair, with pipe in mouth, on the bridge [wing] and actually wait for the dive-bombers to release their bombs before ordering the wheel hard over one way or the other![73]

Given that her bows were pointed east, this means that Peary was at anchor when she was hit. Mel Duke’s comment that the anchor was “short-stayed” is borne out: the anchor was underneath the bow, and still holding the vessel to the seabed. It is not surprising therefore, that the destroyer was hit four or five times by the divebombers: she could not manoeuvre at all. Her sister-ship USS William B Preston could: she was evading the Vals while under power, and her collection of a dozen .50 machineguns, landed from her Catalina charges and mounted on rails on her stern, was proving most effective at keeping them off her. Instead of being sunk, Preston survived, although being hit twice by bombs; with the loss of 14 men, and at a cost of nearly having – coincidentally – her own stern detached.[74]

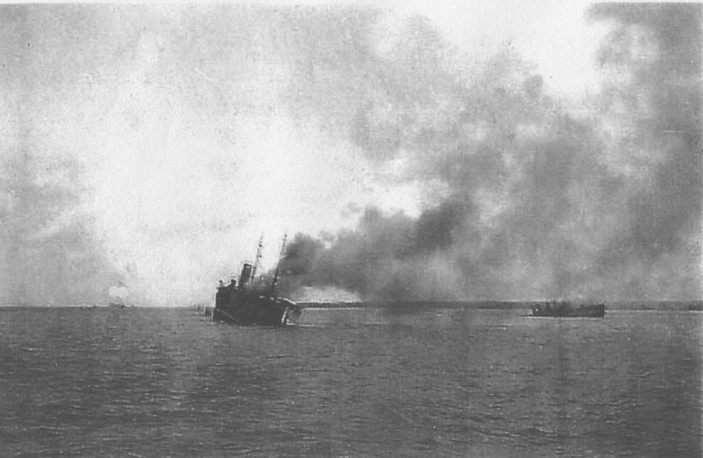

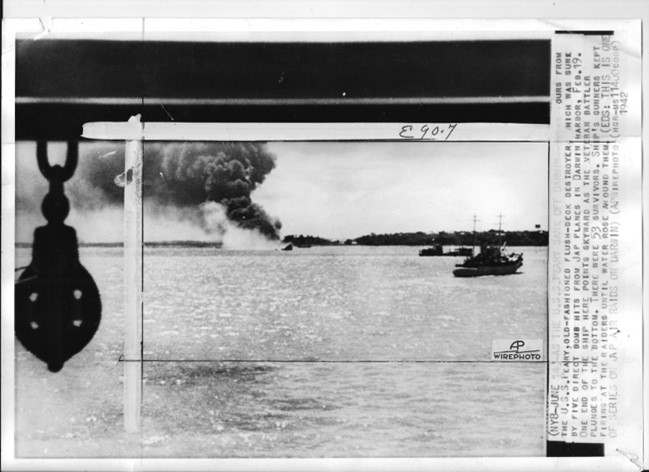

The Peary then eventually did move west, but she could not have been under power. Analysis of the known photographs of her last moments show her very heavily down by the stern, and on fire. The first photograph (left to right, above) chronologically shows the ship very heavily on fire, with a massive plume of smoke being emitted. To the right, as identified by Herb Kriloff of her ship’s company, is the Preston.

The second photograph shows Peary near the Manunda, still on fire. A plot of the bigger ships in the harbour on the day suggests that the drifting Peary would have reached Manunda first. She then (photo 3) neared the tanker British Motorist. In this photo, the fire seems to have diminished, and the rearmost stack of the destroyer to have collapsed. The next two photographs show her sinking by the stern, with the last two showing just the bow.

Conclusion

So what has the discovery of the propellers told us? They have given us the reason why this warship – of several fighting vessels in Darwin Harbour on 19 February 1942 – was the only one to be sunk. The other eight ships that were lost were all freighters or almost unarmed small vessels. The other warships in the harbour survived, due to a combination of more effective armament being used, and being able to manoeuvre. Peary however, was immobile at the outset, and therefore presented an easy target. She was then dealt her death blow: her stern was so smashed it fell off, and the remainder of the ship drifted down the harbour, sinking steadily. She covered a few kilometres in this way, and settled by the end of the raid, probably around 1030.

Peary’s sinking was therefore due to a number of factors. The first was her inability to raise, or release, her anchor. The second factor was the product of the first – she was unable to manoeuvre. Was Peary then probably the very first ship hit, within too short a time from first sighting of enemy aircraft to do anything about getting underway? Third, her lesser armament of her low angle four inch guns and machineguns – rather than the much more effective high angle guns and Oerlikons – gave her reduced firepower. All of this made her an easy target for the Val divebombers, and their pilots knew their work well. Peary may have fought to the end, but she was doomed, and the loss of the destroyer and 88 of her ship’s company was testimony to all of this.

Dr Tom Lewis OAM is a military historian. A retired naval officer, he is the author of 16 books, the latest being Eagles over Darwin – how the USAAF flew air defence for northern Australia for much of 1942; The Empire Strikes South, an analysis of the Japanese air raids across northern Australia in WWII, and Atomic Salvation, sub-titled “How the A-Bombs saved the Lives of 32 million people.” He has also just ventured into medieval history with Medieval Military Combat, a proposal of how infantry fought in the Wars of the Roses.

Thanks to the following for their assistance in this research: Dr Peter Williams, Mr Ric Fallu, Dr Samantha Wells, Lieutenant Commander Des Woods RAN, Mr Clinton Bock, Mr Peter Ingman, Ms Alice West at NT Archives, Rex, Bruce, Digger and others of my regular blog; Vice Admiral Russ Crane AO CSM RAN (Rtd), Mr Michael Wells of the NT Heritage Department, and Mr David Williams of the NT Government.

[1] A note on sources. This work draws on several hundred sources used in prior works by the same author, including Wrecks in Darwin Waters (1990); Darwin’s Submarine I-124 (1995, and 2010); Carrier Attack (with Peter Ingman, 2013), Honour Denied (2016) and The Empire Strikes South, 2017. There is a deal of assumed knowledge in this article derived from these works, and also experience as a serving naval officer. Apologies for any assumptions transferred which may not be clear. The Lowe Report was one of those documents, and was the first comprehensive analysis of the events of the day. It may be seen online at National Archives of Australia. “Bombing of Darwin – Report by Mr. Justice Lowe”. NAA: A431, 1949/687

[2] Excluding the depot ship HMAS Platypus. Of almost identical size was the seaplane tender USS William B Preston, which had once also been a “four stack” destroyer of the same class as Peary. After her modifications Preston had just two funnels, and had been fitted with aviation fuel tanks above the weather deck, so losing some of her Clemson-class appearance. The Clemson class at 314 feet in length were significantly longer than the RAN’s two sloops at 266 feet, although the sloops were more usefully armed, with four-inch high angle guns as their main armament: Warrego with three and Swan with four. They probably had numerous MGs fitted as AA defence at the time, and at some time likely in 1942 had seven 20mm Oerlikons fitted. (See https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-warrego-ii and https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-swan-ii

[3] The 57 vessels are listed in Lewis, Tom and Peter Ingman. Carrier Attack. Avonmore: Adelaide, 2013. (pp: 275-277). One of those lost was HMAS Mavie, but the HMA prefix did not signify a warship, as she was a lugger.

[4] Interview between Grant Treloar and the author, 15 July 2020, in Darwin.

[5] 1. LT CATLETT – PEARY-Report of engagement with the enemy. National Archives Identifier: 133884510 Container Identifier: Roll A3 HMS Entry Number(s): P 17, UD-WW 46. Creator: Department of the Navy.

- Action Report, USS Peary, DD-226, 6 March 1942; USS Peary (DD-226) engagement with enemy – report of Lieutenant WJ Catlett. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf This extremely lengthy (129 pages) collection of documents was collected by E. Andrew Wilde, Jr. as Editor. In the final page of the collection an explanation is given: Wilde, himself retired from the USN, had from 1993 researched WWII destroyers. His findings were not for sale but rather offered to family members of personnel who served on these ships. The PDF file is made up of scans of the original documents; news clippings, and so on. Catlett’s 13 page report listed at 1 is included.

[6] Wilde Collection. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf

[7] Wilde Collection. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf (pp: 1-2 of the report)

[9] Duke, Mel. Interview with the author for Wrecks in Darwin Waters, Darwin 1992. Also used in A War at Home, pp 25-26.

[10] To author Lewis’s knowledge – and he wrote Wrecks in Darwin Waters, requiring years of research and exploration – no anchor from Peary has been discovered. That this would not have been found post-war is not surprising: Darwin harbour is deep, murky, and large. Moreover, Peary’s final wreck site was some considerable distance from where she had started off, as will be explained later. But as Darwin Harbour was cleared of wrecks, and as technology has improved, so too has the exploration of the seabed in this busy port yielded interesting finds. Anchors are significant items: like ships’ bells sacred items, to be displayed and treasured. A destroyer anchor would be large and heavy and not easily taken away. No anchor has been found on the wreck site either, and Fujita Salvage – Japanese and sensitive to reaction against them – would have been more likely to surrender such an item to the 1960 shore authorities when they were salvaging the ship as part of their operations in 1959-1960.

[11] Wilde Collection. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf

[12] Wilde Collection. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf (pp: 443 – typed number rather than actual)

[13] Warrego had the best and most modern AA armament in the harbour – three 4-inch Mk XVI guns in one twin and one single turret. With recent combat experience in the Timor Sea, it is probable that the effective naval AA fire was led by this ship. Her guns were the very first into action as they had been having a gun drill. As the action alarm sounded, the cable party rushed to the forecastle where they hurriedly knocked out the anchor cable pin, leaving the anchor and cable on the seabed. Warrego was then able to manoeuvre in the harbour. When the divebombers arrived, Warrego’s fire control system was overwhelmed with so many fast-moving targets, and her guns fired independently. Swan’s guns were able to engage most aircraft attacking the ship. During a hectic period her CO, Lieutenant Commander Travis, reported the sloop was attacked seven times. “All bombs that were dropped missed astern; according to Travis “presumably because I was steaming at 14 knots into a fresh breeze and using maximum rudder”. See Bradford, John. In the Highest Traditions. SA: Seaview Press, 2000. (p.61) The secondary armament was likely a quad Vickers .303 system, but at some stage in WWII the sloops were fitted instead with up to seven 20mm Oerlikons.

[14] Lieutenant LO Wood, USN. Report to CO of USS William B Preston, 21 Feb 1942. (p. 2) (In the possession of the author)

[15] Kriloff, Commander Herb, USN, (Rtd) Officer of the Deck. California: Pacifica Press, 2000. (p. 131)

[16] Northern Territory Archives Service. Gable, Leonard – NTRS 2855. Unpublished eyewitness account. Box PB 107. (pp. 2-3) Mr Gable was only willing for a paraphrase of his exact remarks to be made.

[17] Mulholland, Jack. Interview with the author. 25 November 2011.

[18] Forster, Pat. Interview with the author, 10 Jan 2012.

[19] Forster, Pat. The Navy in Darwin. Darwin: Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory, 1992. (p. 22, and p. 24)

[20] Ireland, GW. “HMAS Platypus in Darwin during blitz 19 February 1942.” Naval Historical Society of Australia. https://navyhistory.au/hmas-platypus-in-darwin-during-blitz-19-february-1942/ Accessed May 2012. (p.5)

[21] Wilde Collection. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf (page 123 of the report, quoting an article from the Portsmouth Herald, 21 June 1988.)

[22] Marsh, Frank. Diary Entries. Supplied to the author in the 1990s. Published originally in Lewis, Tom. A War at Home, Darwin: Tall Stories, 2000. Extract from third edition, 2007. (p. 25)

[23] “Peary lost but Mel’s back to tell”. Newsclipping from unidentified newspaper, in possession of the authors.

[24] Dale, Able Seaman Harry. Diary extracts. “Life in Darwin on 19th February 1942 and after as experienced by Able Seaman Harry Dale F3298 and by part of the crew on board HMAS Karangi”. North Australia Collection, NT Library. (p. 4)

[25] Boniface, George W. Personal recollections of the bombing of Darwin – 1942 / written in 1987. Northern Territory Library. http://hdl.handle.net/10070/229921. Accessed November 2011.

[26] Bradford, John. In the Highest Traditions. SA: Seaview Press, 2000. (p. 69)

[27] The raid actually started two minutes earlier in Darwin. Nine Zeroes had been tasked to attack Bathurst Island, where a C-53 transport aircraft was on the runway. Six strafed it, with some of the machinegun fire hitting a small radio hut in which missionary Father McGrath was radioing a warning, and then set off for Darwin directly, rather than following the circular track of the main force, which would attack the town with the element of surprise a south-east strike would give. The nine Zeroes attacked ships at the boom net, some eight kilometres from the town. (See Carrier Attack, pp: 95-98)

[28] Kriloff, Commander Herb, USN, (Rtd) Officer of the Deck. California: Pacifica Press, 2000. Kriloff was well known to this author, and the events of the harbour were discussed between us several times. He provided no more detail, during such conversations, than is given in this article as to the last moments of Peary. Whether there is some additional document within US Navy records with a more detailed report from Catlett is unknown, but it would seem unlikely: the level of detail of the Peary files contained in the Wilde Collection would suggest a thorough search was done.

[29] There are 986 articles about Peary in Australian newspapers and gazettes as contained in the Trove database. Many contain extremely wild reporting, and appear generated by the excitement of the bullion story. An analysis of them has been made for this article.

[30] Northern Territory Archives Service. Duke, Melvin & Widick, Dallas – NTRS 1942. Reference copies of oral history sound recordings on compact disks, 1999-n.d. CD 531. (6.20 – 6.30)

[31] Wilde Collection. Portsmouth Herald. “Guns quiet not memories.” 21 June 1988. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf (p. 123)

[32] Townsville Daily Bulletin. “LOSS OF U.S.S. PEARY Suffered Five Direct Hits”. 11 April 1942 – Page 4

[33] Rayner, Robert. The Army and the Defence of Darwin Fortress, NSW: Rudder Press, 1995. (p. 199)

[34] Duke, Mel. Interview with the author for Wrecks in Darwin Waters, Darwin 1992. Also used in A War at Home, pp 25-26.

[35] Northern Territory Archives Service. Duke, Melvin & Widick, Dallas – NTRS 1942. Reference copies of oral history sound recordings on compact discs, 1999-n.d. CD 531. (3.45 – 4.00)

[36] Wilde Collection. “Destroyer Peary, Creaky Navy ‘Tin Can’ Sank Gamely Fighting Swarm of Japanese Bombers.” 6 April 1942. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf (p. 109)

[37] Mulholland, Jack. Interview with the author. 25 November 2011. (p.131)

[38] Bôeichô Bôei Kenshûjo Senshishitsu (p. 351) Also see the Combined Fleet website. http://www.combinedfleet.com Combined Fleet movements 15 February 1942: DesRon 1’s Abukuma departs Palau with the Carrier Striking Force’s CarDiv 1’s AKAGI, Car Div 2’s Hiryu and Soryu, CruDiv 8’s Chikuma and Tone and DesDiv 17’s Urakaze, Isokaze, Tanikaze and Hamakaze and DesDiv 18’s Kasumi, Shiranuhi and Ariake. Accessed May 2012.

[39] Northern Territory Archives Service, NTRS 226, Typed transcripts of oral history interviews with ‘TS’ prefix, 1979-ct, George Haritos, TS 662. (p. 7)

[40] Dale, Able Seaman Harry. Diary extracts. “Life in Darwin on 19th February 1942 and after as experienced by Able Seaman Harry Dale F3298 and by part of the crew on board HMAS Karangi”. North Australia Collection, NT Library. (p. 4)

[41] Dale, Able Seaman Harry. Diary extracts. “Life in Darwin on 19th February 1942 and after as experienced by Able Seaman Harry Dale F3298 and by part of the crew on board HMAS Karangi”. North Australia Collection, NT Library. (pp. 4-5)

[42] Marsh, Frank. Diary Entries. Supplied to the author in the 1990s. Published originally in Lewis, Tom. A War at Home, Darwin: Tall Stories, 2000. Extract from third edition, 2007. (p. 26)

[43] Forster, Pat. The Navy in Darwin. Darwin: Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory, 1992. (p. 24)

[44] Northern Territory Archives Service. Chipman, Bill – NTRS 226. Typed transcripts of oral history interviews with “TS” prefix. TS 177. (p. 7)

[45] Gill, G. Hermon. Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942. Melbourne: Collins, 1957. (p. 593)

[46] Northern Territory Archives Service. Clegg, Don – NTRS 226. Typed transcripts of oral history interviews with “TS” prefix. TS 177. (p. 8)

[47] Northern Territory Archives Service. Eacott, W.E. (Bill) – NTRS 226. Typed transcripts of oral history interviews with “TS” prefix. TS 758. (Tape 3, page 3)

[48] Wikipedia entry on USS Peary, accessed 6 October 2012: “A .30 caliber machinegun on the after deck house and a .50 caliber machinegun on the galley deck house fired until the last enemy plane flew away. Peary suffered 88 men killed and 13 wounded; she sank stern first at about 1300 on 19 February 1942.”

[49] NT Roll of Honour. http://www.ntlexhibit.nt.gov.au/exhibits/show/bod/roh/location

[50] Lewis, Dr Tom. “The American Alliance – founded in blood and sacrifice in Darwin.” Headmark, No. 149, Sep 2013. (pp: 44-45). The NT Roll of Honour also lists the names of the fallen – see http://www.ntlexhibit.nt.gov.au/exhibits/show/bod/roh/location

[51] Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/87967748/willis-charlie-shook National Archives of Australia. Sinking of US PEARY. MP138/1, 603/295/2022. Contains correspondence from 1949 advising the US Navy had no further interest in finding the wreck.

[52] Lockwood, Douglas. Australia’s Pearl Harbour. Melbourne: Cassell, 1966. (pp 164-165)

[53] Wilde Collection. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf (pp: 121-122)

[54] For example: “Oceanic Salvage Company Pty. Ltd” was reported in The Advertiser, 25 Apr 1953, (p. 4)“now in receivership” as selling the wrecks of Pearyand other vessels, despite the destroyer being acknowledged as not found. Other reports name Meigs, Mauna Loa, and Zealandia. A USN LST was reported as being involved in the Peary search in 1948.

[55] Japanese salvage operations – Fujita Salvage Company Darwin – Part 1. Contents range 1956 – 1960. Series number A6980. Control symbol S250368. Barcode 7115269. Copy of a letter from Atkinson to the Commonwealth where he asserts he owns Meigs, Mauna Loa, Zealandia and Peary. (p. 168-169) and proposes bringing Fujita Salvage to town.

[56] Wilde Collection. http://destroyerhistory.org/assets/pdf/wilde/226peary_wilde.pdf (pp: 121-122) Rear Admiral Eller, USN, said in the letter a report in the Sunday Star-Ledger, of 2 December 1956, where Atkinson was reported as selling the wreck to the Okadagumi Japanese company was incorrect, as “the USS Peary belongs to the U.S Navy.”

[57] National Archives of Australia. “Japanese salvage operations – Fujita Salvage Company Darwin – Part 1: Contents range 1956 – 1960. Series number A6980. Control symbol S250368. Access status Open. Barcode 7115269. (p. 88)

[58] It is not known exactly where Peary’s original anchorage was. It is referred to as F3 in her surviving documents, but that does not refer to any known RAN or civilian anchorage.

[59] Interview with Bill Fitzgerald, ex-RAN diver, in a nursing home in Sydney, and T Lewis, 23 June 2020, by telephone.

[60] A conversation between Don Milford BEM, a long-time president of the RSL, and former naval officer, and the author, did not reveal their whereabouts. A fire in the RSL’s Darwin club in 2018 destroyed much of their memorabilia.

[61] See author Lewis’s book Wrecks in Darwin Waters. He dived on the Peary several times to gain material for the book. Well known diver Phil Franklin dived the wreck probably scores of times, and produced a sketch map of the entire site.

[62] A discussion between the author and Atkin’s widow Wendy Hodgkinson in September 2020 did not shed any great light on the Peary salvage. Wendy did not recall any more than one of the destroyer’s guns being in Atkinson’s possession, nor did she recall anything like the Peary propellers being in his yard.

[63] ABC News. “Bombing survivor gets his dying wish”.19 Feb 2009. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2009-02-19/bombing-survivor-gets-his-dying-wish/301680“Dallis” is also reported as “Dallas” in numerous articles.

[64] Lewis, Tom. “What the wrecks of the Sydney and Kormoran tell us about the battle.” Published in various journals, magazines and newspapers following the discovery of both ships in 2008.

[65] The Washington Post. “Searchers find the sunken stern of a doomed World War II destroyer off the coast of Alaska.“ 16 August, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/08/15/searchers-find-the-sunken-stern-of-a-doomed-world-war-ii-destroyer-off-the-coast-of-alaska/Accessed July 2020.

[66] Phys Org. “Japanese battleship blew up under water, footage suggests.” 13 March 2015. https://phys.org/news/2015-03-underwater-blast-japan-wwii-battleship.html Accessed July 2020.

[67] Naval History and Heritage Command. “USS Franklin CV-13 War Damage Report No. 56.” 15 Sep 1946. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/w/war-damage-reports/uss-franklin-cv-13-war-damage-report-no-56.html (Part 4, paragraph 2) Accessed July 2020.

[68] Ordtech. Mk82 500 Lbs Aircraft Bomb. http://www.ordtech-industries.com/2products/Bomb_General/Mk82/Mk82.html

[69] https://drawingdatabase.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Clemson-class_destroyer.gif

[70] Cyclone Tracy levelled Darwin in 1974, and resulted in the sinking of several vessels, the largest being a Navy patrol boat, HMAS Arrow. No other cyclone saw the sinking of a large vessel, nor did the other raids – the Northern Territory was attacked 77 times – see the sinking of large vessels. See the same author’s Wrecks in Darwin Waters, Boolarong, 1991, and The Empire Strikes South, Avonmore, 2017.

[71] Friedman, Norman. Naval Weapons of World War One. Seaforth Publishing, 2011. (pp. 188–191)

[72] Tidal data and graphics produced by Mr David Williams, of the NT Government. Communications with the author, July 2020.

[73] Watkins, Noel. (Son of Chief Yeoman Watkins) “Extract from my father’s diary, Chief Petty Officer Watkins…his own personal interpretation of the Battle and his feelings whilst on board the famous Australian destroyer HMAS Stuart during the ‘Battle of Matapan’: a naval battle between ships of the Allied and Italian fleets”. http://www.gunplot.net/matapan.html March 2001.

[74] Kriloff, Commander Herb, USN, (Rtd) Officer of the Deck. California: Pacifica Press, 2000. (pp: 134-140)