July 2019

An interest in philately has led to a collection of post cards from a century past showing the Pacific colonies of the German Empire. These help bring to life the story of the transit of the German Asiatic Squadron from its base at Tsingtao across the Indian and Pacific Oceans until its eventual demise off the cold and dark waters of the Falkland Islands. This article summarises an award-winning exhibit at the Canberra Stampshow 2014 held in March.

The Colonies

Germany was a latecomer to overseas colonies but made up for lost time in the latter part of the 19th century. To help penetrate world markets a series of colonies was acquired between 1884 and 1899 extending from southern China through chains of oceanic islands to New Guinea. These comprised Chinese concessions at Kiautshou and Chefoo, and colonies/ protectorates at Bougainville Island, Caroline Islands, Marshall Islands, Mariana Islands, German New Guinea, Solomon Islands and German Samoa. A naval base and small garrison was established at the Chinese concession with an administrative centre at Tsingtao. A further administrative centre was at Rabaul in New Pomerania, Kaiser-Wilhelmsland (German New Guinea).

SMY Hohenzollern

Kaiser Wilhelm II had a great attachment for his navy, epitomised by his royal yacht Seiner Majestät Yacht Hohenzollern. With a length of 390 ft (116 m), 46 ft (14 m) beam, 19 ft (5.7 m) draught, displacing over 4,300 tons and capable of 22 knots with a complement of 600 officers and men this was indeed a stately floating palace. She was used extensively taking the royal party on summer cruises and fleet reviews. In twenty years of active service the Kaiser is said to have spent over four years onboard. In June 1914 at the Kiel Regatta officers of the British fleet were entertained on board only two months before the outbreak of WW I. Importantly in philatelic circles the Hohenzollern image was used as the definitive design for nearly all German colonial postage stamps issued between 1900 and 1919.

The Homeward Journey

The first post card which shows the cruiser SMS Gneisnau was posted from Tsingtao on 13 March 1913. In translation this reads: Dear Parents, One day after I sent my last letter to you, this was 13th March, received your parcel by the steamer York containing the bag for a telescope and other nice things. Naturally I was very glad about it and thank you very much and I send my best wishes. Your warm hearted son, Ernst.

On 23 August 1914 Japan declared war on Germany and promptly blockaded Tsingtao but by this time Vice Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee and his German Asiatic Squadron had departed. Following a bitter struggle supported by British troops the Japanese claimed the German concession. There is a post card from this period showing the Japanese cruiser Soya. She had an interesting history, being built in the United States as Variag for the Russian Navy. Being badly damaged in the Russo-Japanese war she was scuttled but salvaged and repaired by the victors. Soya then served as a cadet ship until 1916 when sold back to the Russians. After refitting in Britain she served as a depot ship until wrecked on her way to the breakers in 1920.

Next is a post card from the New Zealand Expeditionary Force of 1,383 men who effected an unopposed occupation of Samoa on 29 August 1914. Life in this quiet backwater was interrupted on 14 September by the arrival of the German cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. An intended dawn raid to destroy Allied shipping and cut communications did not eventuate when it was discovered the only vessel in harbour was an American sailing ship. The cruisers withdrew seeking better game.

A postcard dated 21 September which in part reads: ‘Things are pretty deadly in Samoa and the heat is awful and the bugs, ants and mosquitoes make night hideous and none of the boys are feeling too well and next month when the rainy season commences many no doubt will be down with fever. Two big German warships entered the harbour last week and alarmed the Corps but they cleared out without a fight. They are still off the coast, however, so we may yet have a scrap. Everyone is sick of Samoa and we all want to go to Europe, but suppose we will have to stick it out here for months yet.’

By 22 September the German cruisers had reached Tahiti where they conducted a half-hearted bombardment. This was answered by a shore battery of 4-inch guns taken from the gunboat Zelee. The gunboat had been scuttled to block the harbour and the stockpile of coal set alight. The Germans again withdrew but by this time their intentions were becoming clearer in making for South America.

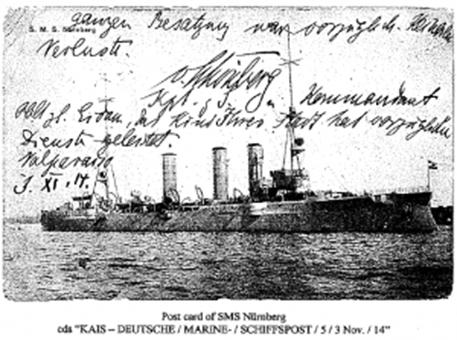

Following the decisive Battle of Coronel where the German squadron defeated a Royal Naval squadron commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, the victors called at Valparaiso primarily to coal ship. From here a post card was sent from the Captain of SMS Nurnberg to the Mayor of Nurnberg dated 3 November 1914. Translated, this reads: ‘A quick note to say the SMS Numberg sank the English heavy cruiser Monmouth on the night of 1st November off the coast of Coronel (Conception Bay, Chile). The weather was stormy. The conditions of the whole engagement was excellent.’ This card most likely went in diplomatic mail via the German Consulate.

The revenge by a superior Royal Naval force over von Spee’s squadron off the Falklands on 8 December 1914 is well known. Only one warship, SMS Dresden (a sister ship of Emden), escaped to hide in the expansive Chilean fiords, until she too was cornered by HM Ships Glasgow and Kent at Juan Fernandez Island (famed home of Alexander Selkirk, the inspiration for Robinson Crusoe).

Finally there are two postcards of British manufacture showing Dresden at Juan Fernandez, taken before her magazine detonated. One card shows a ship’s boat approaching Dresden and the other a close-up of shell splinter damage. On 14 March 1915 after a few shots were fired by both sides Dresden’s Kapitan zur See Ludecke, knowing his situation was hopeless, raised the white flag and sent Leutnant Wilhelm Canaris (later Admiral) to negotiate with the British. However, this was merely a ruse to buy time so that the crew could abandon ship and scuttle her by detonating the forward magazine. Dresden then sank with her battle ensign flying and most of her crew were saved to be interned in Chile.

Publication December 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Peter Brigden