The following are personal accounts by soldiers embarked in the transport ship HMAT Ballarat on 25 April 1917.

Both stories were published on Thursday 19 July 1917 in the Bendigonian Newspaper, Bendigo Victoria.

Written by Corporal R. J. Neave to P. McCahill, of Yalook, Victoria.

Well, old boy, no doubt you will have heard the thrilling news of the loss of the old Ballarat in the ocean. The 25th was Anzac Day. We were to have a holiday. At 1.15 we were issued our water proof sheets. I had just mounted the gangway, and was on deck, when suddenly the sentry said to me, ‘Look!’ and about 600 yards out on the right a white streak, about two yards wide, was coming through the water at us, about the pace of a very fast train, 50 to 60 miles an hour.

No need to wonder what it was. Too well we knew. I shall never forget that white bluish streak tearing along towards us. The officer on the bridge had been already warned, as the boat was slowly turning; but far too slow and too late. The white streak rapidly neared us, and it seemed to be coming right for the middle of the boat, but instead of catching us in the centre, it rushed towards the stern, when ‘Bang!’ I stood firm for the shock, but was thrown off my feet.

A number of our chaps were down in the hold part of the boat, and they said the flour was blown in all directions, whilst the cookhouse was blown to pieces. In the washhouse part the basins were all shattered to pieces, windows in all parts of the boat were broken, and they are thick gloss too. The boat alarm went immediately. This is the most thrilling part of all, and, I am proud to be an Australian, and no doubt you or anyone else would be if you saw the way the brave lads went to their posts.

The officers called out, ‘Don’t rush boys, be steady.’ They all went to their places quickly and fell in line as on all ordinary boat parades. The destroyer, which then came up, could not stop to help us, for the submarine could be plainly picked out. The sailors told us that she had an adjustable periscope, one to pop up and down in a second. Many of our boys saw the periscope from time to time, and the destroyer dodging to get at her. The submarine during these manoeuvres tried to get a second torpedo in. We all expected a second torpedo, but the first was doing its work well enough.

All of us were in line in our places, and could see the destroyer and submarine tactics. We could receive no help from the destroyer while the submarine was about, the former being fully occupied in trying to get the submarine. The ship’s officers got off about 20 boats, and the boys allotted to these boats filled them and put off. About 15 more boats then put off. The boats then jammed, and no others could be got away. All that were left, all in line, stood waiting for the end. Not one boy broke the ranks. It was splendid discipline on the part of all the boys, and it was grand to see how well they stood.

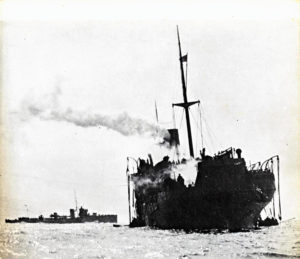

The boats that were filled were now away out in circles around us all well filled up. An aeroplane now arrived buzzing around and using the heliograph. The Ballarat was by this time well on her side, and it was hard to stand owing to the list to port (left side), besides her bow was high up in front, and out of water, with her stern down. The submarine was still about. If the submarine could have got the destroyer, we would all have been shelled in the water, so all the sailors said.

A little later and the water was now in our troop deck, where we lately ate and slept. About three-quarters of an hour after all of us had our boots un laced with laces out ready for when she was to take the final plunge. Everything had been thrown overboard – chairs, boards, boxes, planks, life buoys, and anything that would float. Some of the lads who had been working at the boats went over, and were in the water. They were the last of the companies in the boats that put off.

At 1 pm suddenly on the horizon a speck of smoke was seen, and five minutes later another. We then knew help was coming quickly, but doubted whether they would reach us in time. The destroyers were racing about 40 miles an hour to the rescue. A French aeroplane also arrived. Two aeroplanes were also with us, both continually buzzing overhead and heliographing. The old Ballarat was lying in the same position with the distress signals floating from her tilted mast. The steam was pouring out through the rents by the explosion in the cook house, in the stern part, and the gun lay on its side dismounted by the explosion.

The destroyer rushed for the side of the boat, throwing up ropes. The sailors shouted, ‘Come on, boys. Quick, quick, quick quick’. They kept shouting ‘Jump for your lives.’ Then for the first time the officers called on us, ‘Go on, boys, quick, for God’s sake,’ and down the scores of ropes hanging from the side we slid. Hands were burnt by the ropes, and the boys let go and dropped on to mats, cushions, mattresses, and all kinds of things prepared. This was on the starboard side of the old Ballarat.

In less than five minutes all were off, and we were away. As we moved off, the brave old colonel stood on the bridge and saluted us. The other torpedo destroyer was picking up occupants of the crowded boats. Our boat took on board in less than five minutes 723 soldiers. (That is quicker than we went aboard, don’t you think?) We moved off, keeping about 500 or 600 yards away, when we raced round and round the old troopship as she still lay in the same position. Our boat was crowded. We all sat on deck, legs dangling along the edge, with a wire rope (railing) alongside. Every yard of space was crowded by the boys.

This was the picture at 4 o’clock. Two seaplanes buzzing about, one French one British, and many destroyers passing close by. Empty little boats of the Ballarat were rocking about at their own will on the Atlantic waves. The destroyer beside our own, crowded with khaki-clad forms, and in the centre the poor old troopship that had been our home for 65 days. One of the seaplanes dropped six large bombs in succession about 4.15. This we were told later by some naval officers, put an end to the submarine.

At 5 o’clock our destroyer and another left. Well, we had the fastest ride we ever have had, or, perhaps, likely to have on any boat. We travelled at 20 miles an hour (a little over 23 knots). The sailors were ‘bonza’ chaps absolutely, and had been in the Jutland and Heligoland battles. Many mementoes and keepsakes were given to them. We also gave them our fox terrier. They made chocolates for us, and anything they could possibly give us. We made port 90 miles distance at 8 o’clock. Then for half-an-hour we slowly proceeded up harbor, and at 9 o’clock we were in old England.

We formed up in fours; irrespective of rank, N.C.Os. and men. Colonel McVea stood on the right to take our salute as we moved off. As we passed the colonel said, ‘You good, brave boys.’ My word, I can tell you we felt it rather touchingly. We went to the barracks, where we all had a basin of hot cocoa and a large meat sandwich, and then slept in the midst of some big guns. We were the guests of the sailors, our officers being with the regimental Officers. You can guess how cordially the sailors treated us. In the afternoon we formed up. Then we marched out to a naval railway station, entrained by different brigades, and at 3 o’clock we were off to Amesbury camp at Lark Hill. Till this time the-people could not see us, as we were in the naval yards, but when we emerged, we saw now from everywhere flags flying, whilst every house had its folk at the windows and doors.

At Exeter the Mayoress provided us (on the railway station) with a bun and a cup of tea. We were met at the railway station by a bugle band, and escorted to our camp quarters, where, we gradually settled down.

Torpedoing of the troopship; Ballarat

Written by Private Chas. J. Smith, of Leichardt, son of Mrs. J. Smith, of Bendigo, on 27 April 1917.

“We got within a few hours of land when they got a torpedo into us. I was sitting on the fore well deck hatchway reading and sheltering myself from the cold, when someone called out, ‘There it comes!’ I looked up and saw a torpedo coming straight for where I was sitting.

The alarm was sounded, and we got to our boat stations, the soldiers behaving admirably. There was no rushing, and the boats got away in good time; the sea was calm. I went below to get my pocket book, and my boat got away without me and four others. They would not come back, so we looked about to get into another, but the cry was always the same ‘You don’t belong to this boat!’

We did not get excited or anxious, as we knew the wireless had sent out distress signals. It seemed no time before we, could see destroyers coming. There were about five destroyers and two trawlers. They came right alongside and we got off direct onto them. They would take a load, and then scout round whilst the next got her load, and when all were transhipped, we made off at about 30 miles an hour.

We enjoyed the fast ride immensely, and have nothing but admiration for the British navy. They treated us like old friends, and couldn’t do too much for us.”