July 2017

The following address was delivered by Dr Kevin Smith OAM to members of the Naval Historical Society of Australia in Sydney 18 April 2017.

In 1798 at the Battle of the Nile, the French flagship L’Orient gravely disabled His Majesty’s Ship Bellerophon (known to her crew as the “Billy Ruffian”). Immediately a pack of other British vessels concentrated their attack upon L’Orient.

A flagship carries the commander of a fleet, and bears the commander’s flag.

Amid the wreck and carnage of battle the French admiral’s thirteen year old son stood bravely to his post awaiting his father’s permission to leave. The boy, Louis de Casabianca, died at his post when L’Orient’s magazine exploded. In 1829, a whole generation later, Felicia Hermans wrote her poem “Casabianca”, beginning with the words:

“The boy stood on the burning deck

Whence all but he had fled.

The flame that lit the battle’s wreck

Shone round him o’er the dead.”

Every Australian schoolboy growing up in the 1920s and 1930s, a century later still, heard about or occasionally even read that poem, although very few of us ever remembered any of the details. Many impressionable young minds, however, absorbed its powerful message.

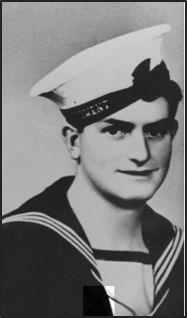

Young Edward Sheean growing up amid the green farmlands and forests of Barrington south of Ulverstone in Tasmania, was one of those who almost certainly would have known the first line of this poem.

At the 1916 Battle of Jutland, ship’s boy John Travers Cornwell, serving on HMS Chester, stood to his duty when all others in his gun turret had been killed. This sixteen year old boy died at his post. Awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously, he became another role model for that same generation of schoolboys. I remember a school book picture in about 1938. In November 2016 at the Imperial War Museum in London I felt privileged to view Jack Cornwell’s Victoria Cross.

In March 1942 the RAN sloop Yarra was on convoy duty in the Timor Sea heading south to Fremantle. A squadron of Japanese heavy cruisers with supporting destroyers attacked the convoy. Yarra was disabled but continued firing until the captain gave the order to abandon ship. Just minutes after giving this order, Lieutenant Commander Robert Rankin was killed when a salvo of 8-inch shells destroyed the sloop’s bridge. As the ship sank, Leading Seaman Ronald Taylor, already known as a keen and courageous sailor, manned a four-inch gun and continued to fire as the waves closed over his ship.

The story of Leading Seaman Taylor’s bravery would surely have spread later among sailors of the R.A.N. back in Darwin.

Out of that ship’s company of 151, only 34 men of HMAS Yarra were able to take to Carley floats. Of these just thirteen were rescued alive. The 21 who perished during five days adrift were said to have either died of exhaustion or lost their sanity, providing a meal for the sharks.

That brings us now to HMAS Armidale. The loss of the Armidale was one of the most painful and bitter episodes in the history of the R.A.N. declared The Australian Defence Force Journal in 2002.

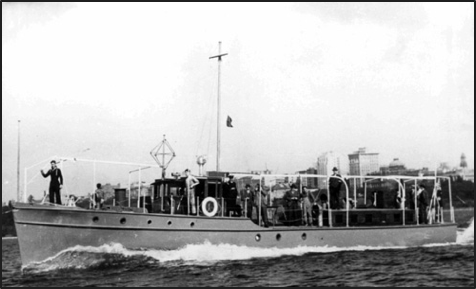

Built at Mort’s Dock, Sydney, HMAS Armidale was launched on 23rd January 1942, one of 60 Bathurst Class corvettes built in Australian shipyards during the war, four of which went to the Royal Indian Navy. 186 feet in length and with a beam of 31 feet they were designed to be the tough, versatile little inshore workhorses of the fleet, they were armed with several Oerlikon 20 mm anti-aircraft cannon. They were capable of rapidly deploying small groups of troops, and normally carried a complement of about eighty naval men.

HMAS Armidale performed escort duties around the eastern and northern Australian coasts and in Port Moresby waters, ready to defend convoys in three dimensions – against submarines, against surface ships and against aircraft. Some of her classmates performed survey and minesweeping duties. However she really could not absorb much damage from enemy attack. She was part of the 24th Mine-sweeping Flotilla.

In September ‘42 the destroyer HMAS Voyager ran aground in Betano Bay (Portuguese East Timor) and her mission was aborted. That mission had been for the relief of the 2/2 Independent Company by the 2/4 Independent Company AIF and to evacuate a number of Portuguese civilians. Sparrow Force in Timor, comprising over time these two independent companies and the Tasmanian-raised 2/40 Australian Infantry Battalion, had been receiving supplies in night time runs from Darwin by the small HMAS Kuru ever since Timor had been occupied by the Japanese in February.

Darwin had been subject to fairly constant air attack since 29th February 1942.

HMAS Armidale arrived in Darwin on 7th November 1942. After three weeks in Darwin she was ordered, with another corvette HMAS Castlemaine to proceed to Betano Bay on 29th November. Leading Seaman Bool, a greatly experienced sailor, displayed exceptional foresight before Armidale sailed out of Darwin, in organising the retrieval of dunnage (planks and other spare timbers) lying around the wharf area) and this was lashed to the deck of the Armidale.

Just a few hours out of Darwin both ships were detected by Japanese aircraft, but were signalled by Darwin headquarters to continue with their mission. They were joined by HMAS Kuru for the operation code-named Operation Hamburger. HMAS Armidale was carrying a crew of 83 plus 3 AIF men (bren gunners) to provide covering fire at the beach for two Dutch officers and 61 Netherlands East Indies troops who were to be put ashore at Betano Bay.

Serving as Loader on the aft port Oerlikon was Ordinary Seaman Edward Sheean. Each Oerlikon was served by a gun crew of three or four: the gun chief who found the targets, the gunner strapped to his weapon with a waist belt and held firmly in shoulder supports, who had the essential role of hitting enemy targets, the loader who fed the ammunition drums of 7-inch rounds to the cannon, with sometimes a second loader. Each gun crew member trained to serve in all three positions.

Kuru arrived early at Betano Bay, on 29th November, and took off about 80 Portuguese refugees, men, women and children, later transferring them at sea to Castlemaine which then proceeded on to Darwin.

Kuru then turned back to Timor. When Armidale reached her destination at Betano Bay that night she could not locate signal fires as had been arranged. She withdrew back to sea to try again the next night to land the Netherlands East Indies (i.e. Indonesian) troops.

On 30th November 1942 Armidale was attacked by an enemy bomber and then by high level formations of nine or ten bombers. She fought back strongly and suffered neither damage nor casualties. This was reported to Darwin, where Commodore Pope arranged for protective air cover.

At 1100 hrs next morning, 1st December, in the Arafura Sea Kuru came under massive air attack which she endured for seven hours before being ordered back to Darwin where she arrived on 3rd December.

Meanwhile Armidale came under persistent air attack again, having been spotted at 1300 hrs on 1st December. The location was 10 degrees South, 126 degrees 30 minutes East,110 kilometers off the southern coast of Timor. By 1430 hrs there were twelve enemy aircraft; nine torpedo dive bombers, and three zero fighters coming in low at 300 miles per hour. An enemy float plane was apparently observing close by. Armidale zig-zagged with vigorous manoeuvres, the deck tilting and pitching while there was a steady response from her Oerlikon ack-ack cannons amid a fierce clatter of machine guns. About 400 kilometers from Australia, she had no air cover. One enemy dive bomber and one fighter were shot down during their lengthy attacks.

The torpedo dive bombers were a new factor not previously encountered in these strife-torn waters north of Australia. It was at approximately 1515 hrs when the ship was hit by two torpedoes, both on the port side. The first exploded just forward of the bridge, destroying much of the radio room.

Signalman of the Watch Arthur Lansbury on the bridge saw that shrapnel had destroyed the ship’s radio, and so no distress signal could ever reach Darwin.

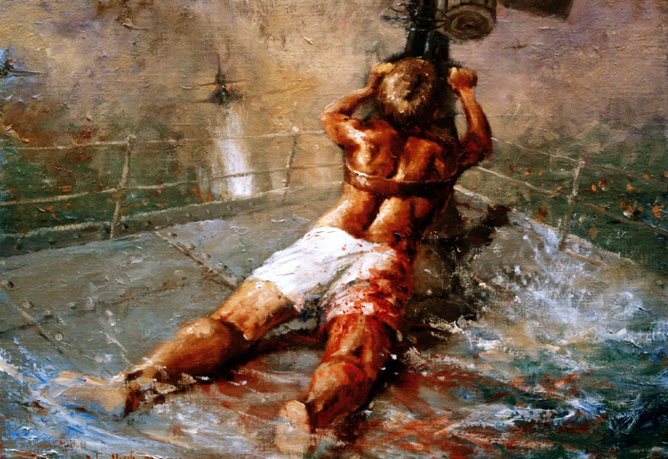

Soon into the water, some of Armidale‘s survivors were strafed and were being butchered by the Japanese Zero aircraft.

Eighteen year old Sheean who at that stage was already among those moving towards the ship’s motor boat to ready it for launching, seeing the plight of his shipmates machine-gunned and dying in the bullet-torn, shrapnel-ripped seas, quickly scrambled back to his anti-aircraft gun about thirty meters away.

Several of the crew were hit as they got the motor boat free just before the second torpedo struck, causing a huge explosion with oil and smoke pouring everywhere. This second explosion was between the engine room and the boiler.

Able Seaman Jack Duckworth on the quarter deck was initially swept off his feet by a great gush of water, but then, under enemy fire, he set about cutting loose anything that would float, including no doubt the timbers lashed aboard by Leading Seaman Bool.

Lansbury was piping “Abandon ship!” on the Captain’s orders when he saw Sheean strapping himself back into his Oerlikon.

Historian Graham Wilson has calculated that Sheean could have been firing for only 16 to 33 seconds, the maximum rate of fire being 450 rounds per minute, with one magazine holding only 60 rounds and thus requiring frequent changing.

From the moment he strapped himself into his Oerlikon with grim determination, Sheean knew he was going to die. Single-handedly he took on the attacking aircraft, bringing down one of them and perhaps damaging two others. He continued firing and died at his post, shockingly wounded a second time as bullets slashed open his chest and back.

Armidale was fully under the waves by 1520 hrs, having taken an estimated three minutes to go down. She was the only Bathurst-class corvette to be sunk by enemy action.

The surviving sailors and soldiers endured further Japanese attacks. For days on end they suffered from the tropical sun, sea snakes and sharks, hunger, thirst, their wounds, and the cruel sea.

The rescue efforts out of Darwin have been criticised as complacent, piecemeal and far too late. The early radio signals, before the first torpedo struck, merely indicated attack by “bombers” without specifying “dive bombers” or “torpedo bombers”. This led to erroneous assumptions back in Darwin, for earlier experience of high level bombing at sea showed that it had rarely been particularly effective. Darwin headquarters had seemed to ignore the loss of radio contact, assuming that ARMIDALE must have survived the presumed high level attacks, while still maintaining radio silence.

The Captain, Lieutenant Commander David Richards, exhausted but still in fighting spirit, the only unwounded officer well able to navigate, loaded the wounded into Armidale’s motor boat and headed for Darwin.

On December 5th they were rescued by HMAS Kalgoorlie. There were seventeen survivors only out of the 22 who had left the carnage of their sunken corvette.

The ship’s whaler or lifeboat was full of bullet holes and waterlogged, but not sinking. The remaining survivors fastened a towline to a damaged Carley float leading, followed by the whaler and a makeshift raft. They had some oars or paddles, but also used their hands. After three days they had not progressed beyond Armidale‘s oil slick.

What followed was a memorable example of resourcefulness and determined effort. They had to turn the whaleboat over and haul its stern, the most damaged part, up onto the improvised raft. Bool later told his wife how they had no firm base for leverage. They had to tread water as they persisted in their efforts to manhandle the heavy lifeboat, first of all to get it upside down. Then inch by painful inch with the tropical sun beating down, their heads immersed again and again, Mae Wests fully inflated, as they pushed upwards, they moved the boat slowly over the edge of the flimsy raft which kept slipping away as it tilted under the added weight of the whaler. We know too little of the details of this episode of their tenacious survival.

They crammed the bullet holes with pieces of their underpants. There was some canvas that could be lashed over the hull. Even so, as Bool told his wife, constant baling with three steel helmets was necessary. One of those steel helmets has been presented to the naval cadet Training Ship Armidale. These resourceful RAN sailors had repaired their bullet-ridden whaler by December 4th and headed south-west for Darwin on the 5th with 29 on board, commanded by Lieutenant Lloyd Palmer who had served as Gunnery Officer of HMAS Armidale.

Painfully sunburned, their limited food and water rapidly diminishing, those in the whaler slowly progressed towards Darwin. Some men became delirious, hallucinating; a few screamed out that they could see breakers and the coastline. When it rained they caught water in their opened mouths and in the folds of their Mae West life jackets.

On December 8th they were sighted by a searching Catalina which dropped food, and were picked up by HMAS Kalgoorlie on December 9th, arriving in Darwin the following day, nine days after the sinking. Theirs was one of the great sea-survival dramas of World War 2.

There was apparently some friction or discord with the Javanese soldiers as well as the Dutch officers. These survivors were given the Carley float and the raft.

The East Indies soldiers on the raft became separated from the others. I have found no further reference to the Carley Float. Those on the raft were sighted and photographed by a Catalina aircraft on December 7th. On December 8th food was dropped to the raft but they were never seen again. They drifted away into oblivion. The stories of other survivors barely or never mention them. They simply disappeared without a trace. Most likely the flimsy construction had broken up in the sea.

There have been occasional but persistent suggestions that a Japanese submarine was most likely involved in their disappearance. Tom Lewis, naval historian and former naval officer, effectively demolishes this furphy in his book Honour Denied (pp 183-185).

Of the ship’s company of 83, 40 died or were KIA. The 3 AIF bren gunners survived. The two Dutch officers died or were KIA. Of the 61 Javanese troops 58 died or were KIA.

Out of a total 149 soldiers and sailors on Armidale there were just 49 survivors, perhaps statistically not quite as devastating a disaster as that of HMAS Yarra.

We most certainly applaud the naming of a Collins Class submarine as HMAS Sheean, while another of the Collins Class submarines has been named for Lieutenant Commander Rankin of HMAS Yarra.

Perhaps the courage of Ordinary Seaman Teddy Sheean is the more dramatic and better known part of the story of HMAS Armidale. However, there is more to the HMAS Armidale story than Sheean’s magnificent, courageous self-discipline.

Leading Seaman Leigh Bool, burned raw by the tropical sun, arrived unannounced at his Sydney home on Christmas Eve 1942. His wife and two children had not known whether he was alive or dead. What a marvelous Christmas for that family!

He told his wife that as Armidale sank beneath him he had dived over the side and had swum astern as fast as he could. The stern of the ship lifted high in the air, its propellers still turning. He saw a Japanese bomber, hit by Teddy Sheean, skimming above the surface trailing smoke until it hit the water with a mighty splash.

Leigh Bool had served eight years in the R.A.N. Earlier in 1942 he had been attached to the depot ship HMAS Kuttabul in Sydney Harbour. When it was torpedoed by Japanese midget submarines he had been ashore on leave. Soon afterwards he was drafted to the cruiser HMAS Perth, but his orders were cancelled the day before she set sail on her final voyage north, where Perth was sunk in the Sunda Strait off Java, in the same month that Yarra went down. Bool was then transferred to HMAS Canberra. As she steamed north to the Battle of the Coral Sea where she was sunk, Leigh Bool had been yet again transferred, at sea, to HMAS Armidale. At last on 1st December 1942 his destiny caught up with him, but he survived.

Another survivor, Ordinary Seaman Col Madigan, was in Armidale for the 1988 dedication of the HMAS Armidale Memorial in that city’s Central Park. He was there again for the sixtieth anniversary of the sinking in 2002. Madigan recalled survivors clinging to whatever they could in the sea, among the oil and the blood, during the first hours after the sinking. Many had been badly injured. He recalled sea snakes swimming around their heads. Sharks brushed past their dangling legs, feeding upon the dead and the injured. He recalled the more fortunate survivors lashing together pieces of flotsam to make a raft as Japanese aircraft returned to strafe them.

Madigan told how, as the whaleboat was hauled aboard HMAS Kalgoorlie, it fell apart. Of the 29 who set out in the whaleboat, 27 were still alive, badly blistered and suffering exposure.

Let us hear briefly, too, from some of the other survivors. Corporal Lionel Clarke, one of the three AIF men: “Things got so bad with the Netherlands East Indies soldiers refusing to give the rest of us a fair go that the Dutch officers threatened to shoot them”.

Stoker Ray Raymond who was in Armidale in 2002 for the 60th anniversary commemoration of the sinking had some gruesome memories: “Joe Currie floated near us for days. Sometimes the sharks would nudge him from underneath and take a bit out of him, but he stuck around just the same. His head had been shot off but I knew it was Joe because of the ring on his finger”. On his successive visits of remembrance to Armidale each December 1st, I came to know Ray rather well. He told me most assertively, “Sheean shot down a Japanese plane.”

Telegraphist Denis Reedman was one of those driven into a crazed state of mind: “I started to jump over the side so that I could swim to Circular Quay. Roberts grabbed me and gave me a bloody great whack on the jaw. I came to lying on the bottom of the boat sobbing my heart out”.

A crewman of HMAS Kalgoorlie never forgot the sight of survivors collapsing on the deck of his ship: “Their condition was appalling with sunburnt, blistered, ulcerated skin caked in fuel oil and salt. They were wrinkled up like prunes”.

The survivors appear to have received little consideration or care back in Darwin, and they were moved back home, in some cases by slow-moving troop train. When Ordinary Seaman Caro and two mates reached Sydney: “Our hair was still matted with oil, we were unshaven and we looked pretty haggard”.

Frank Walker wrote his book HMAS Armidale: The Ship That Had to Die in 1990. In it he gave details of the subsequent wartime Naval Enquiry, and he is scathing of the treatment of the men of HMAS Armidale. He wrote, “The unpalatable but inescapable truth is that the operation was botched up, then covered up”

There have been representations made since that Sheean deserved a V.C., and that it should now be awarded posthumously. Many such requests have emanated from Tasmania his home State, but all have been unsuccessful. The simple truth of the matter is that recommendations of VCs for WW2 naval personnel, men serving on His Majesty’s Australian Ships have had to be approved by the British Admiralty.

We are now seeing the birth of a legend among the citizens of Australia’s southern island, not so much relating to an honour denied, although there’s plenty of that too, but a legend akin to that of Leonidas the valiant Spartan who defended the pass at the head of 300 warriors against a vast Persian army during the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC, in ancient Greece so many centuries ago. Our own new Australian legend of a great Australian naval warrior who died in unwavering, single-handed defence of his ship will assuredly spread and grow in the years ahead. Let us nurture that legend.

In May 2002 I went to sea out of Darwin on HMAS Whyalla, to conduct research on behalf of the Deputy Maritime Commander RAN. We sailed into the Arafura Sea and westward to the Ashmore Reef, but that adventure for an old bloke is another story. I came home somewhat inspired to do something about perpetuating the name of HMAS Armidale. Immediately our Armidale Sub-branch RSL took up the challenge, and I found myself chairing a small committee of former sailors. The Mayor and the local Federal Member proved to be very strong supporters. Our motto or catchcry became “Armidale city wants its warship back in the fleet”. The local press promptly came on board and soon we had the backing of an entire community. An RSL secondary schools art competition on the theme “Our Pride in the Courage of HMAS Armidale” received a DVA grant and the principal judge was Colin Madigan. Former Minister for Defence the Hon. Ian Sinclair and the RSL’s National President Major General Peter Phillips (ret.) gave influential behind the scenes support for our campaign. We were elated to be successful in our endeavours for a new HMAS Armidale, but more than that, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the sinking, the Chief of Navy announced that the next more versatile and larger generation of twelve Australian naval patrol boats would be known as the “Armidale” Class. A contract for $533 million had been signed with Defence Maritime Services near Fremantle, construction had been started on the lead vessel HMAS Armidale, and this first of the new class would be launched (although not commissioned) the following year.

In 2005 several members of the Armidale RSL Sub-branch with our Mayor and his wife travelled to Darwin for the commissioning of HMAS Armidale on 24th June. Two survivors from 1942 were there, Roy Cleland and Will Lamshed. This patrol boat continues today in service with the Royal Australian Navy. Its motto “Stand Firm” on the ship’s crest symbolises the strength of both the ship and the city of Armidale.

In response to widespread public opinion that Teddy Sheean should have been awarded a Victoria Cross, the Defence Force Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal was instructed by the Australian Government to thoroughly investigate the matter.

There were numerous submissions to the Tribunal. Some were quite brief assertions of support for such an award. The RAN Corvettes Asssociation made a strong submission which included survivor’s statements, letters from Members of Parliament, an extract from Hansard and copies of several newspaper articles.

Wireman William Lamshed stated: “A torpedo struck our port side amidships, causing a huge wall of water. The doorway burst open and I stepped into it, which took me over the side. I was a man overboard, with a ringside position to witness the sinking as the ship broke into halves. The rear section was leaning on an angle to port when the after Oerlikon started firing. I saw tracer bullets hitting a Zero which flew over my head and hit the water some distance away. I learned later it was Teddy Seean, who strapped himself into the gun and shot down the Zero. To me this had to be one of the bravest things that could be recorded . . . Teddy Sheean will always be a hero to me.”

The evidence of Ordinary Seaman Ray Leonard was quite clear: “Struck by a torpedo, Armidale almost immediately developed a list to port and began to sink. . . . On my way down from the bridge to the starboard deck a group of us tried unsuccessfully to launch the whaler. . . . I abandoned ship by jumping off to starboard . . . and as I did so I heard in addition to the enemy’s machine gun fire, a different sound which I recognised as coming from Armidale’s Oerlikon gun. . . . I met up with my shipmate Ordinary Seaman Russell Caro . . .Subsequently . . Caro expressed to me his admiration for Sheean’s heroic behaviour. . . during the six months that we were shipmates on Armidale, and during our friendship over many post-war years I regarded Russell Caro as a man of integrity”.

Dr Ray Leonard after the war, eventually became Chief Psychologist of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Ordinary Seaman Donald Pullen told the enquiry:

“I recall how Ted’s first movement was toward the ship’s side, as if to jump into the sea . . . but . . Ted was wounded at the same time. He did an about turn, struggled to the after Oerlikon and strapped himself in and began firing.. . . He had at least one kill, and another plane damaged which disappeared into the sea in the distance. . . . He’d have little hope of escape, particularly if he was wounded again.”

A statutory declaration from Ordinary Seaman Colin Madigan stated: “My action station on the bridge was in the Asdic cabinet and when the order to abandon ship was given I had difficulty extricating myself because of my Mae West which was inflated. I could hear Teddy Sheean’s Oerlikon firing all the time. . . .This act was awe-inspiring. It enters that universal temple Pantheon which records the world’s great legends . . .”

Colin Madigan was commissioned as an RAN Sub-Lieutenant in 1945. Then, as a civilian he resumed his pre-war architectural studies and eventually became one of Australia’s most distinguished architects, especially noted for his design of the National Gallery and the High Court in Canberra, and some of the buildings of the University of NSW in Sydney.

Stoker Ray Raymond climbed the ladder with difficulty from the engine room as the ship leaned to port, then walked down the ship’s starboard side to reach the sea. He informed the enquiry, “I swam about forty yards away from the ship, when confronted by a torpedo which was painted red and green. How it didn’t hit me I will never know, but it proceeded on its way and hit the ship between the engine and the boiler room with the result that the ship was blown in halves. The bridge section of the ship sank first. The after section righted itself from the tilt and the after Oerlikon came into sight being manned by Ted Sheean. . . . Many were killed as a result of this low level attack by the Japanese, but many more would have been killed had it not been for Ted Sheean’s brave action and sacrifice of his own life.”

Able Seaman Ted Pellett’s statement indicated that.” Sheean and I were both together. We made for the motor boat. I had a tommy-axe in my hand and I chopped the after-fall and Sheean was right alongside me. They were strafing us at the time. He was going to get into the motor boat with me. He was right alongside me, then he made a decision to go back and have a go at them.. . . He didn’t have to do it. A lot of people would say he deserved a V.C. and some would say he was an idiot. . . .it was each man for himself.”

In the House of Representatives on 4th June 2001, the Member for Braddon spoke at some length. I shall mention just a brief extract or two: “Unfortunately Sheean’s conspicuous gallantry was only briefly recorded by his CO. . . . The Australian Commonwealth Naval Board headed by a seconded Royal Navy officer had to send recommendations to the Admiralty in London. . . . the Australian government of the day . . . did not avail itself of its newly established powers issued by a royal warrant on 31 December 1942 to recommend the Victoria Cross.”

In 2013 the Tribunal concluded that Sheean’s actions displayed conspicuous gallantry but that the Tribunal could not recommend the award of a V.C. This finding was not particularly popular and thousands unsuccessfully signed petitions to set the findings aside.

© Copyright: Dr Kevin Smith

About the Author: Dr Kevin Smith OAM

Dr Smith has authored numerous books, major reports and articles over the last 16 years.

He has a post-graduate degree from the University of Florida, PhD and other qualifications from the University of New England. He has been a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Educational Planning (UNESCO, Paris), Sheffield City Polytechnic and the University of Nottingham. His professional career included being a School Principal, Head of a Centre for Administrative Studies, Armidale and Chairman of the Council of Presbyterian Ladies’ College, Armidale.

During 2006 he was President of the Armidale Sub-branch, RSL having served within Australia in the Hunter River Lancers, NSW Mounted Rifles and the Australian Regular Army during the 1950s. He was for nine years a member of the RSL’s NSW State Tribunal and formerly Vice-President of the NSW Military Historical Society.

He has wide experience as a consultant on morale in large organisations including the RAN Submarine Squadron, Australian Army and U.S. Army.

Dr Smith’s has a strong commitment to telling the Borneo story of Australian POWs. His mission is to document and preserve details surrounding the fate of so many of the prisoners which may otherwise be lost forever and has made many visits to Borneo some of which were pilgrimage tours which he led.

In 2002 he was invited to visit the Ashmore Reef on an operational border protection patrol of the Royal Australian Navy, and subsequently was closely associated with moves for the commissioning of a new HMAS Armidale, which became the first in the Armidale Class of patrol boats.

He was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia in 2004 for service to the community particularly through Lions Clubs International of which he is a Past District Governor (1974-75 and 1991-92) , with over 55 years membership.