By Eric Deshon

The following story was first published in the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) Volunteers’ Quarterly newsletter ‘All Hands’, Issue 103 in June 2018. It is based on Eric Deshon’s account of being marooned in Arnhem Land along with five shipmates. It was brought to light by the ANMM volunteers’ oral history program.

It was 1958. Although both my parents came from rural Western Australia I was always captivated by ships and the sea. After school I went to work in a bank which I found terribly boring so I joined the Naval Reserve. I did a trip on HMAS Fremantle, a Bathurst class minesweeper, to Shark Bay and thought it was terrific. I would have been 19 or 20 at that time. I resigned from the bank and had another job all lined up but I was down at the Training Depot and somebody said that the HMAS Fremantle was leaving the next day, to go up north for a couple of months and I thought I’d love to go.

My mother who was a bit horrified but said, ‘Probably for the best. You’re a bit of a nuisance here!’, so I wrote a very brief three liner to the company I was going to join, said, ‘Sorry’, packed a bag and went down and joined the ship.

Well, away we went up north, 92 of us, and as it happened, we were away for six months. I had no reason to come back so it didn’t matter. I was the only reservist on board and they called me the ‘Sunday Sailor’, or ‘Rocky’ the usual name for a reservist. I was an Ordinary Seaman, and you can’t get any lower than that.

Life on board the ship was always a bit rough and tumble but it was very strictly regimented in many ways in its voluntary discipline. Watch keeping rolled on day and night. There were never any issues about this or that. We sailed to Darwin and joined five other ships and from there we sailed 400 kilometres due west to a large uncharted area called Sahul Bank. We were out there for two or three months and day after day we sailed up and down taking depth soundings and samples of the ocean floor. I suppose it was quite monotonous but I enjoyed it because it was it was all new. Here we were mapping a part of Australia which was totally unknown.

The survey came to an end and then the ship was given a new role; patrolling the northern coastline because there was a Japanese fishing fleet operating just outside of our territorial waters and they wanted to be sure that they didn’t fish Australian waters. We cruised up and down the Arnhem Land coast but never saw a glimpse of any Japanese. We did see a couple of pearling luggers but otherwise there was very little going on.

Two weeks was about as long as we could stay at sea with the amount of fuel that we carried so when the ship was scheduled to return to Darwin to resupply, the Navy decided to land a party ashore in Arnhem Land to make a token representation in the ship’s absence. Think about it! As if we were ever going to see a Japanese fishing fleet as we sat on the beach in a slab of country about the size of Victoria. So, there we were; a sub lieutenant and five sailors. They rowed us ashore in the naval whaler with some food, a rifle and a sleeping bag apiece and landed us at the estuary of a small river, at a place called Boucat Bay. No radio, no tents for shelter, and a few days’ supplies. I don’t think this river even had a name but there we were.

We had nothing to do of course. We had the rifles and we used to sit on the edge of the estuary and there were sharks that came in. Their fins would surface as they swam past us and we took pot shots but there was really nothing much else to do. Of course, it was stinking hot and we slept in sleeping bags and I cannot believe it now but we were just above the high-water mark and this was crocodile country.

About a hundred metres behind us there was a small Aboriginal community who were living a very traditional way of life. Now in 1958 Europeans had not made a lot of contact with these people. They didn’t bother us but there was one gentleman who used to come over the small sand hill regularly – six foot, upright well-built man, fairly typical of the males up there – and he’d say to me, ‘Mittamiligan im miligimbi’. He would say it again and again, and then he would go away. I really didn’t know what he was trying to convey. We all thought about it over two or three days and I said, ‘I think there is a place somewhere along the coast called Millingimbi. Would he mean Mr Milligan at Millingimbi?’

Anyway, I indicated that I might like to go and see this Mr Milligan and the others agreed, so when this man Jackie Jackie – I never did know his Aboriginal name – appeared the following morning, I went with him. It was still dark but we set of immediately to walk across the estuary which was at least a hundred meters wide. The water was black, it was chest deep and I carried my loaded .303 rifle across my head, no safety catch on because I knew what was in the water. And my Voitlander, a great little camera, in an army haversack.

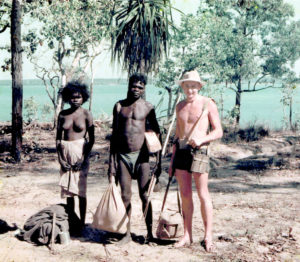

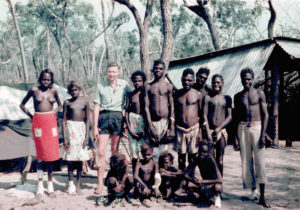

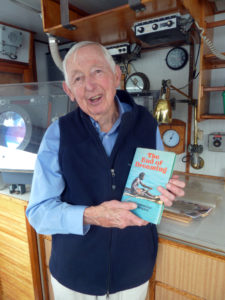

| From top: Eric with his Aboriginal companion and guide and his number two wife; patients at the leper colony at Maningrida; and three happy castaways after the arrival of the “storepedos”. |

I didn’t know how far I was going. I thought I was possibly going to a mission settlement. I had total trust in this man. There was no option! Walking with this Aboriginal was like running for me. We just walked flat out – for me, flat out – straight across the country. Then halfway through the morning we came to this large lake covered with lilies.

The Aboriginal man brought his number two wife with him. She walked behind us probably 30, 40 or 50 metres behind us, always by herself. We stopped briefly at the lake and then my Aboriginal companion decided he would walk through so once again I was walking through waist-deep water with no idea what was on the bottom and when we came out the other side, I was hugely relieved. His poor wife was still coming along behind and I thought, ‘Gosh, if something goes wrong, I couldn’t save her.’ We probably had a 5 or 10 minute break and off we went again through the bush. No tracks. No nothing. I was simply walking into the unknown.

At around midday I realised that we were coming into a clearing and there was actually a small airfield. At this point some 50 Aboriginal kids turned up. They had the hugest grins and the most beautiful teeth. They were all jumping around calling out ‘Navy man! Navy man! And I thought how the hell do they know? Well, this is the Bush Telegraph at work. They knew well in advance that I was coming. I walked into the settlement with them feeling something like the Pied Piper.

The settlement was a government settlement called Maningrida, not Millingimbi, and it was only two or three years old. There were two or three small buildings with tin roofs and hessian walls. There was not a lot else except a leper colony. There were four Europeans: Mr. and Mrs. Drysdale., There was a young lady called Eileen who was a nurse and another man who was called Mr. Milligan, They didn’t seem particularly surprised at my arrival but welcomed me and I stayed at their place. They gave me a bed and next to my bed there was my .303, a high powered .22 and a shotgun ‘For the snakes…’, as Mr Milligan explained.

They said, ‘We’re very busy at the moment because the lugger has arrived. It comes every six months.’ With that I went down to the waterfront and I joined in with the Aboriginals who were carrying the stores ashore off the lugger. I stayed with Mr. and Mrs. Drysdale for about three days and they fed me but I was always hungry. They were living off tinned sausages, tinned chops, tinned beans. The one thing they were making was fresh bread in a wood fired oven. That was the best bread you could ever have. But after a meal I used to sit back and think I could eat that again quite easily.

The Aborigines lived in a community nearby and they were living in lean-to’s and bark huts. I think they were looking after themselves, not with government rations. There was a leper colony with an Aboriginal who had trained as a medical assistant called Philip. He and this lady Eileen would go out every morning and look after the lepers. That was a most awful disease; people with large patches of flesh that were just rotting on their arms and legs. Some people had already lost a foot or a finger. In those days there was nothing much they could do for them. But I noticed that they were quite well dressed.

On the second day a RAAF Lancaster bomber started circling and I wondered what on earth it was doing. The Drysdales had a peddle radio and they got onto Darwin, who got onto the Air Force Base, and this all took some time. I said, ‘What’s this plane doing? It can’t land here, the mission strip is too short’

And the message came back that to say they were looking for a lost Naval shore party. ‘Oh’, I said, ‘I’m part of that.’ Because they couldn’t land, they dropped down these ‘message sticks’. They’d broken up a packing case on board and they chalked message saying, ‘Show us the direction of the Naval shore party…Which way?’ If I hadn’t been there, they would have had no idea.

Then it was time for me to go, to walk back. I’m not too sure how far we were from the Navy camp but it must have been all of 20 kilometres through the bush and that’s quite a walk. For supplies I had a tin of pineapple juice and a slice of bread

The aborigines all started to get agitated and I said to Mrs Drysdale, ‘What’s going on?’ She said, ‘I think they’re all going with you. It happens all the time like this. They all get excited. They pack up and they go and there’s nobody here and then they all come back again. They just go walkabout.’

And, sure enough when I left, there must have been 50 of them, at least – men, women and children. The men had their spears and Jacky proudly carried my rifle for part of the way. I kept the bolt and the ammunition in the haversack.

This time we walked back along the beach which was much further. By dusk we had gone about halfway and they decided to stop and make a bed in the sand. I slept behind a small sand dune because the wind blows at night and it’s actually very cold and all I had was a pair of shorts and a shirt and I froze. I had nothing left to eat that night. And in the morning they decided to move on; so did I. We had nothing to eat that morning, either, and we walked all day along the beach and at nightfall we got to the river.

The Navy shore party was on the other side. It was just getting dusk and if you know the tropics it gets dark very quickly. The aborigines started to wade across this river and before long there were only a few of us left and I thought, ‘I know what’s in the water but I can’t stay here. I have to go.’ As I stood on the edge my whole shuddered from tip to toe and I broke out in a cold sweat. The water was black by this time and I waded across in the company of two or three others. Again, with a loaded rifle across my head.

| Some of the “message sticks” dropped to Eric and the Drysdales at Maningrida. |

When I reached our camp on the other side, they said, ‘Our ship was due but hasn’t come.’ And I said, ‘Well, the Navy’s not coming for some time. It’s been delayed or gone somewhere. The Air Force had a plane out looking for us and I have these bits of timber that say that they don’t know where we are.’

‘We saw a plane flying past way out to sea.’

‘That’s the plane that was looking for us. Did anybody try to attract their attention?’

‘No.’

Next morning, my aboriginal companions moved on further east. We had virtually nothing left to eat but no food meant nothing to them. Most of them just kept going out into those wetlands.

We had no idea where the ship had got to or when we might be picked up, so the following morning two of our shore party, both stokers, crossed the estuary and started the long walk back to Maningrida.

The next day the remaining four of us were sitting on the beach wondering where life was taking us and suddenly there was a huge roar and a Lancaster bomber from Darwin flew over the top of us at a ridiculously low altitude. They made a large circle and then dropped two parachutes with food. They were called ‘storepedos’ but the problem was it was low tide and they dropped these one or two hundred meters offshore, in the sloppy ocean floor and we had to drag them in. But I might add that the parachutes made good tents.

A couple of days later I was standing on the shore line and just gazing out to sea when suddenly I saw a ship. It’d probably been there for some time and I hadn’t seen it. We all watched as they lowered the whaler and rowed ashore to pick us up. We had been lost for nearly two weeks.

| The castaways on return to Fremantle, 19th September 1958, as seen on page 15 of the West Australian ‘Daily News’; from left to right, Brian McDonald, Trevor Smith, Eric, John Bowd and Sub Lieutenant Charles Thompson. |

Oh, what happened to the two stokers who walked off to Maningrida? On the afternoon they arrived, a missionary, flying his own small plane, had landed briefly on his way to Darwin. The two stokers hitched a ride into Darwin and made their way down to the ship – to the amazement of all on board.

When I was ashore I realised that I had experienced, for a brief time, what we Europeans call the Aboriginal “Dream Time”. But I find it difficult to put into words. With an Aboriginal community in the middle of Arnhem Land in the 1950s, the sun came up, you hunted, ate, and then the sun went down. There’s a very strict social and spiritual structure but it’s a world that doesn’t need possessions. You are born, you live this way, you die. There was no clock, no month, no year – there was no nothing. That is difficult for us to comprehend

By Editor

A review of HMAS Fremantle’s Report of Proceedings for the month of August 1958 revealed that the ship was the Duty Pearl Fishing Surveillance Vessel from 2 August until relieved by HMAS Cootamundra on 22 August. The landing party of seven landed on 1 August was tasked with observing Japanese pearling boats and preventing contact with local aboriginals in Boucaut Bay.

Having returned to Darwin for fuel on 4 August Fremantle was, on 5 August tasked with going to the aid of HMAS Emu in the vicinity of the Wessel Group of islands. Emu was experiencing trouble with its pumping equipment. After rendering technical assistance to Emu, HMAS Fremantle returned to Darwin for fuel and eventually recovered the landing party on 12 August. The landing party had been ashore for 11 days instead of an intended 6.

No mention is made of the two sailors making their own way back to Darwin by air and the aircraft which dropped supplies to the party on 9 August is described as a RAAF Lincoln aircraft.