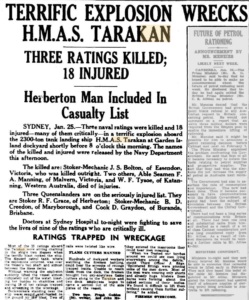

With Australian’s focussed on celebrating Australia day and long weekends the anniversary of the tragic explosion and fire in HMAS Tarakan (I) on 25 January 1950 passes relatively unnoticed most years. This paper revisits the disaster which claimed the lives of seven sailors and one dockyard worker.

By David Stratton

LST 3017 was one of six Landing Ships Tank (Mark 3) which were loaned by the Royal Navy to the Royal Australian Navy in 1946. The others were LSTs 3008, 3014, 3022, 3035 (renamed HMAS Lae) and 3501 (renamed HMAS Labuan).

LST 3017 was taken over by the Royal Australian Navy and commissioned at Trincomalee as HMA LST 3017 on 4 July 1946, under the command of Acting Commander George M Dixon DSC RANVR. She was renamed Tarakan on 16 December 1948.

Tarakan served in Australian and New Guinea waters as a general purpose vessel, but was mainly used for dumping condemned ammunition at sea.

The Fire

At precisely 8.26 on the morning of Wednesday 25 January 1950, a violent explosion punched across the water. A mushroom of black oily smoke speckled by 44 gallon drums rose high in the sky above HMAS Tarakan moored alongside at the naval dockyard.

Tarakan was a tank landing ship, one of thousands mass produced during World War II. In the post war years she had become a supply ship for the Royal Australian Navy. She had ferried supplies to Heard Island in the Antarctic and Manus Island on the equator, and was used to dump obsolete ammunition off the coastlines of Australia.

‘It was a strange bang – it seemed to go var-oom and sweep on for minutes until it swelled into a great rattling boom,’ said an eyewitness, who was walking 100 feet from the doomed ship. ‘The Tarakan seemed to swell like a boxer expanding his chest, wisps of dust eddied from the ship’s plates and then, like a flash of lightning, a flame swept the ship from end to end. Dust and smoke mushroomed to mast height and then came the explosion. Forty-four gallon petrol drums rose in the air like patterns of depth charges,’ he said.

Lieutenant-Commander Ferguson, Captain of HMAS Lae, a sister ship of Tarakan, was one of the first to reach the ship’s deck. He leapt from his vessel berthed alongside and dragged an injured worker across the deck. He could hear the roar of flames beneath his feet and feel the heavy fumes of petrol and methyl chloride, a dangerous refrigerant, hanging over the ship.

Lt Cdr Ferguson passed the wounded workman over the ship’s side to two first aid men and then mustered a rescue party to search for other casualties.

Altogether 25 men were caught in the burning ship. A quick inspection revealed that two decks had been crushed together by the explosion – there was no exit. Within minutes the steel decks became so hot that the rescue party had to leave the ship.

Twenty-two of the trapped men were in the seamen’s mess which the explosion had plunged into inky darkness. Fittings were torn from the bulkheads and the whole space was littered with distorted tables, forms and bunks. The darkness did not last for long. A dull red glow aft showed through the swirling dust and smoke. The glow spread and trapped men moaned and screamed as the heat seared their bodies.

One man fought his way to a porthole and pushed his head through. He saw rescuers on the wharfside and pleaded hoarsely, ‘Hurry for God’s sake, we’re roasting alive’.

Two seaman were trapped under a fallen bulkhead close to the flames. Three of their messmates crawled through the debris to reach them. Sobbing with pain as the hot steel burnt the flesh from their hands, they lifted the bulkheads and dragged the trapped men clear.

Five and a half minutes after the explosion, dockyard and civil firemen in asbestos suits and wearing respirators boarded Tarakan. Water and foam was poured on to the deck but after a few minutes the rescue party was forced back; there was no way of reaching the trapped men.

Flames close to fuel tanks

A second explosion was expected at any minute. Flames were now close to the ship’s fuel tanks. Great clouds of oil and bitumen-fed smoke blanketed out the sky. Fire parties from the cruiser Hobart berthed nearby were pumping hundreds of tons of salt water into the ship. There was a danger that the weight of water would capsize the vessel so the pumps were stopped.

In the early afternoon the still smoking Tarakan was taken in tow by a tug and moved into dock for an inspection of the hull. The ship was flooded to prevent a second explosion.

The death toll rose to five within 24 hours; by the end of the week it was eight. Seven of the victims were sailors and one a dockyard worker. A mass funeral for five of the dead was held in Sydney and the cortege passed through silent streets lined with thousands of bare-headed mourners.

Outcome:

Eight days after the catastrophe a Navy board of inquiry reported: ‘Apparently the explosion occurred when an electric fan which had been circulating fresh air into the men’s mess was turned off. Petrol fumes had been noticed previously, and when the fan stopped, the circuit was broken, throwing an arc. This ignited the petrol vapour in a 2,000 gallon fuel tank adjacent to the ill fated mess deck’.

Tarakan was not decommissioned by the Navy although a survey showed the hull to be sound. On 12 March 1954 she was sold on behalf of the United Kingdom Ministry of Transport to EA Marr & Sons Pty Ltd, of Mascot, Sydney, for breaking up.

Source: Cairns Post, Thursday 26 January 1950, available at NLA Trove, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/42654939?searchTerm=terrific%20explosion%20wrecks%20h.m.a.s.%20taraka

References:

George Hicks, Garden Island Boilermakers: Heroes of the Tarakan Disaster, Naval Historical Review September 2007 edition, available at https://navyhistory.au/garden-island-boilermakers-heroes-of-the-tarakan-disaster/

Lew Lind, ‘Tarakan’s Death Blast Shocked Garden Island’, Garden Island: Vol. 2 March 1984 Number 1 p. 13