- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Naval Aviation, History - WW1, WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Australia I

- Publication

- March 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

A summary of this paper was presented at a conference held from 30 September to 01 October 2014 at the Universidad Andres Bello, Chile on the maritime history of South America throughout WWI.

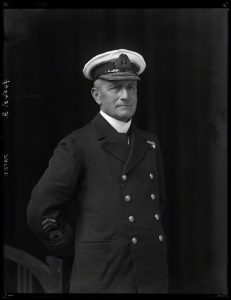

Important men mostly leave behind them a written trail of evidence of their passing. Admiral Sir George Patey is an exception with no voluminous book or memoirs following in his wake. However there are plentiful references to his time as commander of the Australian Fleet and from these and other sources we are able to find out something about this remarkable man and his importance to Australian naval history.

Appointment as Rear Admiral Commanding the Australian Fleet

On 4 March 1913 the Admiralty announced that Rear Admiral Patey had been appointed to the command of the Australian Fleet. The Times of that date commenting upon the appointment says: Rear Admiral Patey is an officer of wide experience and high attainment, and he is well qualified by his tact and temperament for the new post. And new post it was, as Rear Admiral commanding the Australian Fleet replacing the Royal Naval Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Station. That change however was a little way off as the new Australian Fleet was at this time being assembled in England and would not sail from Portsmouth for their new homeland until July 2013.

Early Life

George Edwin Patey was born at Montpellier near Plymouth on 24 February 1859 to a naval family, his father a Captain in the Royal Navy having the same name set and his mother Lucinda the daughter of Vice Admiral Thomas Russell. He entered the Royal Naval College as a cadet on 15 January 1872, just shy of his thirteenth birthday.

Action in South America and South Africa

Young Midshipman Patey’s first sea posting was to HMS Shah. Shahwas commissioned in Portsmouth on 14 August 1876 by Captain F.G.D. Bedford, RN carrying the flag of Rear Admiral Algernon Frederick Rous de Horsey, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Squadron. She was a large composite (sail and steam) frigate of over 6,000 tons, built with iron frames but wooden clad and armed with 26 guns and 4 torpedo launchers.

Patey’s first taste of action was off the Peruvian coast on 29 May 1877 during an engagement (later known as the Battle of Pacocha) between Shah and HMS Amethyst and the Peruvian rebel turret ship Huascar. The armoured Huascar proved virtually impenetrable to British guns and Shah fired the first British torpedo used in anger, but it missed the target and Huascar escaped. On Shah’s return voyage she was diverted to South Africa to assist in the Anglo-Zulu War. Sub-Lieutenant Patey was sent ashore to fight with a naval brigade and received the Zulu Medal.

Gunnery Specialisation and Naval Intelligence

Upon return to England with promotion to Lieutenant in August 1881 he joined the gunnery school HMS Excellent and after completing his course remained on the staff. In May 1885 came a posting to the gunnery training ship HMS Cambridge then based at Plymouth. The following year he moved to more distant shores in the corvette HMS Sapphire for squadron gunnery duties on the China Station. He then returned to Cambridge as Senior Staff Officer in 1889 and was later lent for staff duties in the Mediterranean Fleet. Promoted to Commander in 1894 he served as Executive Officer of the battleship HMS Barfleur during the Allied occupation of Crete in 1897 following the Greco-Turkish uprising on this island. Patey was appointed to the Naval Intelligence Division in 1899 and on promotion to Captain on 1 January 1900 became Assistant Director of Naval Intelligence. This was an important time in the future development of naval ships and armament giving rise to the Dreadnought era and the impending arms race with Germany.

Marriage and Command

On 12 March 1902 Captain Patey married Mary (Mollie) Augusta Yorke-Davies, the only daughter of the eminent Harley Street physician Dr Nathaniel Yorke-Davies. They were later to have two children, Rodney and Lorna. Lady Mary is remembered as an elegant chatelaine of Sydney’s picturesque Admiralty House with a Sydney newspaper columnist referring to her as ‘gay, natural and full of enthusiasm’.

Somewhat unusually Patey, who had never held command, was in November 1902 appointed Captain of the newly commissioned battleship HMS Venerable,flagship of Rear Admiral Mediterranean Fleet. In 1905 a second command beckoned in the same fleet as captain of another battleship HMS Implacable.For a big ship man in a hurry there was a quiet period when in November 1907 he became Inspecting Captain of Boys’ Training Ships. At this time the Royal Navy received most of its recruits from these training ships who were well grounded in naval routines and proved excellent seamen. This sinecure was not to last long with promotion to Rear Admiral on 2 January 1909 and later the plum posting in the Home Fleet as commander Second Division of the Second Battle Squadron.

An Australian Command

Since federation of the Australian colonies in 1901 and formation of a Commonwealth Government a greater degree of independence was sought from the Imperial authority which extended to local command of defence forces. Amalgamation of colonial forces took time and replacement ships were sought to meet the needs of the newly formed Pacific nation. A small but well balanced force of new ships was built and Britain and by 1913 these were being readied for their voyage to the far end of the world.

Rear Admiral Patey’s appointment as the first commander of an Australian Fleet may have been influenced by the following. Firstly Sir George Reid, an advocate of Federation and former Prime Minister, who in 1910 became High Commissioner in London with a responsibility for overseeing construction of the Australian fleet – Lady Florence Reid launched HMAS Australia.Second was the influential retired naval captain Robert Muirhead Collins (later Sir Robert) who was the initial Secretary of the Commonwealth Department of Defence before his appointment as Official Secretary to the High Commission. The final member of this interest group was Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson1who was instrumental in designing the structure for an Australian Fleet.

Admiral Patey’s Australian Service Record shows little of interest other than that he was appointed as a Rear Admiral in the Permanent Naval Force (PNF) on 23 June 1913 for a period of at least two years at a salary of £1,095.00 pa with Table Money of £1,642.10. On 14 September 1914 he was appointed a Vice Admiral in the PNF at a salary of £1,460 pa with the same Table Money plus War Service pay of £409 pa.

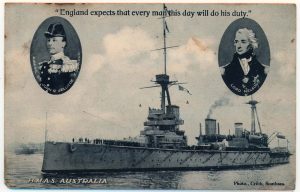

HMAS Australia

The famous Admiral Sir John (Jacky) Fisher is credited with modernising the Royal Navy and will forever be associated with the new type of battleship HMS Dreadnought which made other capital ships obsolete. Following this success Fisher envisioned another slightly smaller ship with similar offensive power but greater speed. To achieve this, armour protection was sacrificed for greater speed in a new type of vessel called a battle-cruiser. In 1905 the first of a new Invincible class was laid down. After lessons learned from their service three more improved Invincibles commenced, HM Ships Indefatigable and New Zealand and HMAS Australia.Each was of 18,800 displacement tons, with a length of 590 feet (179.8 m), 80 feet (24.4 m) beam and 30 feet (9.2 m) deep draught. Their armament comprised 8 x 12-inch, 14 x 4-inch guns and 2 x 18-inch torpedo tubes. They had a maximum speed of 25 knots, an economic endurance of 6,700 nautical miles and complement (as flagship) of 850 men. Later experience at the Battle of Jutland demonstrated shortcomings in their design when three battle-cruisers were sunk. Interestingly at this time the battle-cruiser Kongo was also being built in England for the Imperial Japanese Navy and she sailed from Portsmouth a month after Australia.With the latest 14-inch guns Kongo was one of the most heavily armed ships in the world.

Following successful gun, torpedo and machinery trials Australia commissioned at Portsmouth on 21 June 2013, under the command of Captain Stephen H. Radcliffe, RN. The battle-cruiser was inspected by HM King George V on 30 June 2013 and on that occasion Rear Admiral Patey received the singular honour of being knighted by his sovereign on the quarterdeck of Australia,an honour first bestowed by Queen Elizabeth on that legendary English hero and bane of the Spanish Main, Sir Francis Drake, some three centuries before.

On 21 July 1913 Australia sailed from Portsmouth and proceeded via Cape Verde (taking on 2,000 tons of coal) to Cape Town. Here she met with the new light cruiser HMAS Sydney which had departed from England before her. The locals turned out in force to welcome the visiting ships and were keen to compare the battle-cruiser with her sister ship New Zealand which had visited a few weeks earlier on her homeward voyage. The two ships then proceeded to Jervis Bay where they were joined by the cruisers HMAS Melbourne and HMS Encounter(on loan from the RN) and the destroyers HMA Ships Parramatta, Warrego and Yarra and readied themselves for an official fleet entry into Sydney Harbour.

A Personal Interview

The arrival of the first Australian Fleet in Sydney on 4 October 1913 was a platform for celebration and rejoicing – the nation had come of age. In those times public figures were often remote and courting media attention was unusual. It was therefore something of a coup when two days later on 6 October that the then Vice Admiral Sir George Patey granted an interview to a correspondent of the Sydney Morning Herald. A few weeks previously he had a similar dialogue with a newspaper correspondent in Cape Town. In keeping with the traditions of ‘The Silent Service’ these interviews were restricted to precisely five minutes. A summary taken from these newspapers provides a personal glimpse of the man.

He is 54 years of age, of medium height, with aquiline features and iron grey hair. There is an engaging smile beneath sternly set features, which underlies a genial personality. Like the majority of sailors he is a modest public speaker but demonstrates a degree of eloquence. He is an admirer of the Henderson Scheme for naval defence. The Admiral noted that half of the men under his command were Australian and they came with good physique. The other half were from the Royal Navy or the Reserves. It would take some time to train all of these into a cohesive unit but they were all the same to him, he said, and they would all be officers and men of the Royal Australian Navy. He noted the opportunities in the Royal Australian Navy were greater than in Britain for promotion and that the pay was much better.

To those on the lower deck, often with discerning powers of observation, their Fleet Commander was known as ‘Gentle Annie’. A popular song of this period had lyrics which included: Fair and lovely Annie, Your gentle ways have won me. Their observation is possibly a parody on stern looks but a gentle demeanour.

War comes to the Pacific

Having worked in naval intelligence and attending war college before his flag appointment Patey had witnessed the great arms race between Britain and Germany and would have known better than most that a war was imminent. He therefore wasted no time in ensuring his new fleet was well trained and prepared. At the commencement of hostilities between Britain and Germany on 4 August 1914 the RAN was on a war footing and ready for action. At this time his Fleet comprised:

Battle cruiser Australia

Light cruisers Melbourne& Sydney and Brisbane (building)

Light cruiser Encounter(lent by Admiralty)

Torpedo boats Parramatta, Yarra and Warrego (and three others building)

Submarines A.E.Iand A.E.2

Ex-colonial and Admiralty ships Pioneer,Protector, Gayundah, Childers and Countess of Hopetoun (mostly obsolete)

The French cruiser Montcalm served with the Australian Fleet during 1914

The Japanese cruisers Chikuma and Ibukialso supported the Australian Fleet early in WWI.

At the start of the war there were 3,800 men in the PNF and 1,646 (mainly Reservists) in the Naval Brigade. At its peak, before large scale demobilisation in 1919, these numbers had increased to 5,250 PNF and 2,817 in the Naval Brigade. In addition there were 3,092 cadets under compulsory training schemes at the start of hostilities which had increased to 3,834 by 1919. Of the PNF figures, about twenty per cent were on loan from the Royal Navy.

On 2 August 1914 the Australian Naval Board established an Examination Service to check arrivals and departures of shipping at defended ports. Two days later on declaration of war this led to the capture of a number of German merchant ships that were in port or within Australian waters. On 3 August the RAN was placed under Admiralty control; on the evening of the same day the German passenger liner Seydlitz managed to slip quietly out of Sydney Harbour and make passage to Chile where she joined von Spee’s squadron.

While the Great War, afterwards known as WW I, was mainly a European conflict, it extended into the Indian and Pacific theatres as the Allies pursued the conquest of German colonies, closed German merchant trade and eliminated the threat from German naval forces. The most significant military action was the Japanese siege of Tsingtao, in what is now China, but smaller actions were also fought in German New Guinea and German East Africa. The German Navy also skilfully used commerce raiders and mined Australian and New Zealand waters with significant effect. Patey’s ships were also responsible for protecting convoys carrying troops and provisions to the Middle East in support of the Mother Country.

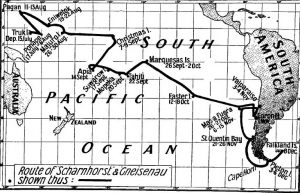

In August 1914 the only direct threat posed to both Australia and New Zealand was from the German East Asiatic Squadron, principally comprising the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and light cruisers Nurnberg, Leipzig, and Emden, under the command of Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee. The light cruiser Dresden, at this time in the West Indies, made haste south to join von Spee, just managing to elude a British squadron under command of Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock making its way down the east coast of South America and she was able to transmit to von Spee details of Cradock’s squadron. Dresden joined her sisters off Easter Island on 12 September. Another ancient light cruiser Geier, operating off German East Africa, also attempted to join von Spee but was hampered by being low on fuel and with mechanical problems, forcing her to make to the neutral port of Honolulu. Here she was hemmed in by Japanese cruisers and was eventually interned by the United States.

The only Allied naval ship in southern waters that could outclass the enemy was Australia, as by this time New Zealand had returned to the First Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet. New Zealand commenced her return journey leaving Auckland in June 1913 making a leisurely passage across the Pacific as far north as Vancouver before proceeding south, two years before the opening of the Panama Canal2, with calls at Callao and Valparaiso before rounding Cape Horn and making her way to Britain where she arrived in November 1913. During this period the New Zealand Station remained dependent upon naval support from the Royal Naval China Station with an allocation of four older light cruisers and one sloop.

Relative Naval Strengths in the Pacific Theatre

While the Royal Navy outnumbered all other nations in the size and strength of its fighting ships it had allowed its China Station to decline in favour of building its forces in the Home Fleet to combat an increasing German presence. In August 1914 the China Fleet under command of Vice Admiral Sir Martyn Jerram had the cruisers HM Ships Monitor, Hampshire and Yarmouth and five destroyers at his disposal at his main base of Weihaiwei. The battleship HMS Triumph3, the light cruiser HMS Newcastle and the French cruiser Duplix were further south at Hong Kong.

The East Indies Station based at Colombo had been reduced to the obsolete battleship HMS Swiftsure4and the light cruiser HMS Dartmouth. The Imperial Russian Fleet at Vladivostok was depleted by the Russo-Japanese War with new tonnage going to the Baltic Fleet. The flagship Zhemchug when visiting Penang was to meet Emden with devastating results.

Although not required by the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance, Japan pledged support to Britain and formally declared war against Germany on 23 August 1914. While the European navies might not yet consider Japan an equal and doubted its capabilities, Japan had a vast fleet of 14 battleships and battle-cruisers, 13 armoured cruisers, 10 light cruisers and 50 destroyers and other vessels. As time would tell its standards of training were of the highest order and its ships highly efficient.

Immediately upon entry into the war Japanese forces were concentrated as the major partner in an Anglo-Japanese assault on the German fortress and naval base of Tsingtao (modern Qingdao) which was known as the Gibraltar of the East. The German garrison was stoutly defended and did not surrender until 7 November 1914. Admiral von Spee had left behind an antiquated Austro-Hungarian cruiser Kaiserin Elizabeth and some small craft which were lost in battle. In turn German torpedo boats sank a Japanese cruiser and a destroyer. It was a vicious siege with over 2,000 Allied (mostly Japanese) casualties and 700 German casualties.

While the Japanese Second Fleet was involved at Tsingtao, ships of the First Fleet joined with British, French and Australian ships in searching for von Spee’s cruisers. The Japanese also took the opportunity to increase their footprint in the Pacific through the capture of German colonies in the Caroline Islands, Marshall Islands and most of the Mariana Islands.

Belatedly another British naval squadron under Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock was dispatched around Cape Horn to plug the remaining escape route open to the Germans. The Fourth Cruiser Squadron which also doubled as a training squadron was renamed the South Atlantic Squadron. It mainly comprised obsolete ships and was not a front line unit suitable to take action against a determined and superior enemy.

Australian and New Zealand Pacific Campaigns

Pre-empting further Japanese expansion south of the equator, both Australia and New Zealand quickly formed expeditionary forces leading to the capture of German colonies. The first land offensive was the occupation of German Samoa by New Zealand forces. The campaign to take Samoa ended without bloodshed after over 1,000 New Zealanders landed on the German colony, supported by an Australian and New Zealand squadron led by Australia and the French cruiser Montcalm.

In August 1914 the Australian Government raised an Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force of 1,500 Army volunteers and 500 men from the Naval Brigades to secure German colonial possessions to the north of Australia. These troops were transported in the P&O liner Berrima which had been commissioned into the RAN. After a sweep of New Guinea waters by Patey’s squadron with no sight of von Spee’s ships a detachment from the Naval Brigade landed to silence a radio station at Bita Paka. They were repulsed by German led native troops but with reinforcements the radio station was captured with minimum casualties. It took several more days to reach the headquarters of the German Governor at Tooma and he proved obstructive. But following a bombardment by Encounter the German territories were surrendered on 17 September. Tragically the submarine AE1which was on patrol off Rabaul on 15 September was lost without trace with her crew of 34 officers and men. With the capture of two small German ships most of the squadron was dispersed with Encounter sent to patrol between Fiji and Samoa on the lookout for enemy ships.

The German East Asia Squadron – We seek him here – We seek him there.

The elusive Scarlet Pimpernel who frustrated French authorities in their search for him gave rise to that famous parody ‘We seek him here – We seek him there’. Maximilian Graf von Spee became such a character frustrating a huge Allied naval force seeking him throughout the vast expanse of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It was inevitable that he would eventually be discovered and defeated but he gave a great account of himself and the officers and men under his command.

At the declaration of war the German squadron was more than capable of defying the British China Fleet with the only potential threat coming from the Australian Fleet then many thousand miles to the south. Von Spee was particularly wary of the Australian flagship describing her as superior to his entire force. When Japan entered the war with her huge fleet it was inevitable that the German East Asia Squadron withdraw from Tsingtao and attempt to make its way back to the Fatherland.

Von Spee first brought his forces to Pagan Island in the Marianas where they reprovisioned and readied themselves to fight their way out of the Pacific. To retain the initiative von Spee devised a strategy designed to confuse and split the superior forces opposed to him. In this way his concentrated cruiser squadron would have a chance of clearing the Pacific or at least finding shelter in a neutral South American country. Emden was despatched from the main squadron to create as much noise as possible in the east of the Indian Ocean and disrupt shipping lanes. The armed merchant cruiser Prinz Eitel Friedrich was dispatched into the west of the Indian Ocean. This would divert Allied forces and permit the remainder of the squadron to move southeast away from potential Australian and Japanese forces towards the west coast of South America.

For a time Allied forces were unable to locate von Spee’s squadron, but in early September 1914, it attacked the British outpost on Fanning Island and destroyed the wireless station there. On 14 September, Emden appeared in the Bay of Bengal, where she sank five merchant ships and captured a sixth. Furthermore, on 22 September she bombarded Madras and on 27 September attacked Penang and sank the Russian cruiser Zhemchug and a French destroyer Mousquet. While in the Pacific, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau bombarded Tahiti on 22 September.

Emden’s luck ran out on 9 November 1914; when attempting to destroy radio installations on the Cocos Islands to the south of Java she was intercepted by the light cruiser Sydney.In the RAN’s first major engagement Emden was driven ashore and destroyed by gunfire with the loss of 136 men killed, plus 70 injured. The Australian losses were 4 killed and 16 injured.

Patey’s Dilemma

Admiral Patey considered the German’s could adopt one of four options:

- Break out into the Indian Ocean via Malaysia

- Reach the Indian Ocean by proceeding south of Australia

- Continue operations in Australasian waters

- Make for the coast of South America and thence reach the South Atlantic

Patey believed they would take the fourth course but felt unable to act until he had definite evidence of their intentions. On 17 September 1914 Patey received a telegram from the Admiralty advising of a changing situation with the appearance of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at Samoa and Emden in the Bay of Bengal. He was ordered to take Australia and Montcalm and cover Encounter from potential attack in New Guinea and then search for the enemy cruisers. Melbourne was to be used at the Admiral’s discretion and Sydney for convoying Australian troops to Aden in company with a Royal Navy and Japanese cruisers. Hampshire and Yarmouth from the China Fleet would search for Emden.

Patey, after conferring with his French counterpart Rear Admiral Albert Huguet, left Rabaul on 1 October taking his squadron east hoping to make radio contact with the Japanese ships operating to the north. While they were able to hear the Japanese they failed to respond to messages transmitted from the Australian flagship. Meanwhile the Australian Naval Board informed Patey that the German heavy cruisers had again been located when they raided

Tahiti and their light cruisers were operating off the South American coast. The Admiralty, which had received conflicting advice from British merchant ships, thought the heavy cruisers might return towards Samoa, Fiji or New Zealand. Accordingly they ordered Patey to make his headquarters at Suva.

Chile and the Falklands

The next engagement was fought off the coast of Chile, this was the decisive Battle of Coronel on 1 November 1914. A British squadron under Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock was sent to destroy the German ships. Craddock’s squadron was possibly more reliant on tradition of a naval service which had not suffered defeat in more than a century than the standard of its ships and training. The outcome was a devastating defeat with two British cruisers sunk and the remainder being forced to flee. Over 1,500 Royal Naval sailors died including the admiral while only three Germans were wounded.

The euphoria did not last long as the Admiralty, stung by the defeat at Coronel, despatched a powerful squadron from the Grand Fleet to intercept the Germans. This squadron was under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Frederick Doveton Sturdee, who wore his flag in the battle-cruiser Invincible. Included in his squadron was another battle-cruiser and six cruisers. Sturdee had previously served on the Australia Station and had been the first captain of New Zealand. The two forces met off the Falkland Islands on 7 December. The German ships were now low on coal and with most of their ammunition expended were no match for the superior RN ships and were soon defeated. Admiral Von Spee went down with his flagship and perished with about 2,000 of his countrymen.

The only German vessels to escape the Falklands engagement were the light cruiser Dresden and the auxiliary Seydlitz. Seydlitz fled into the Atlantic before being interned by neutral Argentina, while Dresden turned about and steamed back into the Pacific. She then took to commerce raiding without much success, until March 1915 when her engines began to fail. Without means of getting repairs, the German light cruiser sailed into neutral Chilean waters at the island of Mas a Tierra and here on 14 March she was cornered by British naval forces. After a short engagement in which four of her crew were killed Dresden was forced to scuttle with her crew interned by Chilean authorities.

The war ends in the Indian and Pacific Oceans

The AMC Prinz Eitel Friedrich had made her way from the Indian Ocean via Cape Horn into the Atlantic where she was unsuccessfully hunted by Royal Naval ships. On 10 March 1915 she sought sanctuary at the United States port of Newport, News where she was interned.

In 1915 the aged light cruiser Pioneer joined the East African campaign and on 6 July in an indecisive action engaged the cruiser SMS Konigsberg and later was involved in shore bombardments. A disguised armed German raider Wolf remained at large and sank 12 Allied merchant ships and laid minefields in shipping lanes off the north of New Zealand and the south east of Australia. Wolf was never captured and her mines were not finally swept until 1918. The sailing ship Seeadler also used as a raider was more of a romantic nuisance than a threat, she eventually foundered on an atoll in the Society Islands but her crew and prisoners escaped ashore. Her captain von Luckner took an open boat to Fiji with a small party where they were captured and interned in New Zealand. The remainder escaped by capturing a passing schooner which reached Easter Island with her crew interned by the Chileans in October 1917. The United States was involved in at least one hostile encounter with Germans in the Pacific during WWI when on 7 August 1917 SMS Kormoran was scuttled at Guamto prevent her capture by the auxiliary cruiser USS Supply.

Australia continues into the Atlantic

It was not until early December that Australia was ordered to proceed to England for service with the Home Fleet. She arrived at Valparaiso on 26 December where she took on coal and

then transited the Magellan Strait where a propeller was scraped on a rocky outcrop. She however continued and intercepted the German auxiliary Eleonore Woermann which was

captured and her crew taken off before being sunk by gunfire, Australia firing her only shots in anger during the whole of her service. Australia called at the Falklands to assess any

potential damage before proceeding to England, arriving at Plymouth on 28 January 1915.

On reaching England Australia was made flagship of the Second Battle-Cruiser Squadron in company with New Zealand and Indefatigable. Admiral Patey being senior to the upcoming star Sir David Beatty, was persuaded to accept a new posting as Commander-in-Chief of the North American and West Indies Station which included Melbourne and Sydney. Vice Admiral Patey’s flag was hauled down in Australia on 7 March 1915 although command of the Australian Fleet was not handed over to his successor Rear Admiral William Pakenham until 23 September 1916. On 1 January 1918 Sir George Patey was promoted Admiral.

Reflections

The British strategy of concentrating its capital ships in Home waters at the expense of its China Fleet was sound providing it gave the Japanese authority to assume Allied responsibilities in this region. Not surprisingly it was reluctant to do this and as a result a smaller German force was able to exploit a poorly implemented command structure of a much superior Allied force.

The naval strategy adopted by the Allies appears disjointed and was hampered by the promotion of local enterprises for territorial gains of ex-German colonial possessions. Delays were also encountered by the reluctance of the Australian and New Zealand Governments to allow their troop transports to proceed without superior convoy protection – possibly unknown, their only potential enemy was the lone cruiser Emden.Had Patey taken Australia directly across the Pacific and joined Cradock’s squadron the disaster off Coronel might have been avoided.

After the Battle of Coronel, on 15 November, the Australian Governor-General was prompted, possibly urged by Patey, to transmit a message to the British Government complaining of bungled naval strategy and time wasted over Samoa and New Guinea rather than first seeking to destroy the enemy’s ships. He reaches the conclusion that ships of the Australian and China Fleets have been ineffective owing to remote and poor Admiralty control and that this has allowed the concentration of German forces off the coast of Chile with lamentable results. These comments would not have endeared Patey to the Admiralty and have adversely affected his future career.

George Patey had but one opportunity for greatness in bringing von Spee to action but this was never within his grasp. There were too many distractions, some planted by the enemy’s clever ruse which divided the Allies and had them chasing shadows. The greatest offenders were those seeking territorial gains at the expense of perusing the German squadron with all speed leading to its destruction. Patey must have been frustrated with a difficult command structure which left the Australian Naval Board virtually ineffective and, in dealing with a remote Admiralty. By the time Patey reached England he may have been past his prime and others such as Beatty, possibly with lesser talents, had found favour in seeking prized commands.

Admiral Sir George Patey should be remembered as a highly proficient officer who took a fledging Australian Fleet to its new homeland and ensured it was prepared and ready to take its place as a fighting unit amongst the world’s leading naval powers. This was achieved and as our first Fleet Commander he provided a sound platform for others to follow. Not leaving a great trail of personal documents there is difficultly in judging his character, suffice to say he was intelligent, energetic and resourceful man who maintained dignity and was held in high regard by those who served with him. In January 1919, at his own request, Admiral Patey was placed on the retired list; he lived in Plymouth and died there on 5 February 1935 aged 76. His wife Lady Mary predeceased him, having died at Plymouth on 27 May 1930.

1 In May 1910 retired Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson was invited by the Australian Government to provide advice on future naval infrastructure. His somewhat optimistic report provided the blueprint for future planning of ships, depots and manpower.

2 Although officially opened in August 1915 the Panama Canal was not available to belligerent nations in the Great War until after United States participation in the war in April 1917.

3 & 4 Ironically both Triumphand Swiftsure were laid down as the Chilean battleships Constitucion and Libertad but owing to financial difficulties were bought off the stocks by the Admiralty.

Bibliography

Bromby, Robert, German Raiders of the South Seas, Sydney: Doubleday, 1985.

Carlton, Mike, First Victory 1914, Sydney: William Heinemann, 2013.

Delano, Anthony, They Sang Like Kangaroos – Australia’s Tinpot Navy in the Great War,Melbourne: Arcadia, 2012.

Department of Defence (Navy), An Outline of Australian Naval History, Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1976.

Etherton, P.T. & Hessell Tilman, H., Japan: Mistress of the Pacific, London: Jarrolds, 1933.

Fazio, Vince,Monograph– The Battlecruiser HMAS Australia – First Flagship of the Royal AustralianNavy, Sydney: Naval Historical Society of Australia, 2000.

Gillett, Ross,Australian & New Zealand Warships 1914-1945, Sydney: Doubleday,1983.

Grove, Eric (Ed), Great Battles of the Royal Navy, London: Bramley Books, 1994.

Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War I, London, 1919.

Jose, A.W.,Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18, Vol. IX, The Royal Australian Navy,Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1928.

Newspapers – various reports from newspapers published between 1913 and 1916 in Australia, Britain, New Zealand and South Africa.

Roberts, John A., Warship Monographs – Invincible Class,London: Conway, 1972.

Saxon, Timothy D., Anglo-Japanese Naval Cooperation, 1914-1918,Faculty Publications and Presentations, Paper 5, 2000. ˂http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/history_fac_pubs/5˃. Accessed 03 March 2014.

Service Record George Edwin Patey – The National Archives (UK) ADM/196/39

Service Record George Edwin Patey – Australian National Archives

Tromben-Corbalan, Carlos, The Chilean Navy: Two Centuries of Service, Sydney: Naval Historical Review, December 2013.