- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2024 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Birth of the Queens

The great ocean liners and sister ships Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary feature as two of the most important troop carriers in the annals of Australian military history, with their names perpetuated to this day by later generation ships now mainly satisfying the tourist trade. Our interest goes back to the first of these ships which also operated as His Majesty’s Transports between 1939 and 1946.

During the inter-war years British, French, German and Italian shipping companies were competing with express superliners on transatlantic voyages. The British lines White Star and Cunard began construction of new large liners but owing to the Great Depression, work ceased with the companies appealing for government assistance.

One of the last ships completed at John Brown’s yard on the Clyde during the Great Depression was the Canadian Pacific luxury liner Empress of Britain. With much fanfare, in a publicity coup she was launched on 11 June 1930 by the Prince of Wales1, then possibly the most popular and definitely the most photographed man in the world. At 42,500 tons with a speed of 24 knots she was a magnificent, very large and fast ship. During the winter months when the St Lawrence Seaway was frozen over she went on world-wide cruises. To accomplish this, her outer two propellers were removed but she could still make 22 knots with her fuel consumption nearly halved. On her first voyage to Australia in 1938 she was the largest liner to have visited our shores, attracting huge crowds. After the launching of the Empress of Britain the Clyde shipyards and the associated steel making industries were all but closed with just one ship, a yacht for a Greek millionaire, under construction. Considering the risk too great, Lloyds would not underwrite new ships proposed by White Star and Cunard.

As a boost to the depressed economy the Government eventually provided financial assistance to reinvigorate ship construction. This was agreed, provided that the two companies merge, and all work cease on the White Star ship, with only the Cunard ship to be completed. Work recommenced on the then unnamed Queen Mary, which sailed on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on 27 May 1936. She was a great success and in the same year won the prestigious ‘Blue Ribbon’ for the fastest transatlantic crossing.

On 9 March 1921 at John Brown’s Clydebank the Prince of Wales launched the Union Castle liner Windsor Castle,believed to be the first time a member of the Royal Family had participated in the naming of a merchant ship. She became a troopship and was sunk by an aerial torpedo in the Mediterranean on 20 March 1943, with nearly 3000 troops and crew rescued by her escorts; remarkably there was only one fatality.

With the success of Queen Mary, Cunard had the confidence to contract for a second ship to provide a weekly service across the Atlantic, with the order going in 1936 to John Brown of Clydebank who had built her sister. The new ship Queen Elizabeth was launched by her namesake on 27 September 1938 with her daughters the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret in attendance. King George VI was absent owing to the Hitler/Chamberlain talks trying to avert a war crisis. As her place in the yard was now needed for warship production she had to move quickly to a fitting out berth. On Sunday 3 September 1939 Prime Minister Chamberlain announced that Britain was at war with Germany. The very next day bookings for her maiden voyage were cancelled and Queen Elizabeth’s upper works were painted a dull pussers grey, but she retained her black hull. Fitting-out now concentrated on mechanical and electrical work with passenger accommodation being unfinished. To keep the enemy guessing as to her destination it was rumoured that she was bound for Southampton for final docking and completion. A steaming crew for a (Home Trade) coastal voyage were signed on. Dummy crates were sent to Southampton and hotel rooms were booked for her crew.

The Safety of American Shores

In the meantime, Queen Mary’s last pre-war passenger voyage departed Southampton on 30 August 1939 with a record 2332 passengers in addition to her 1035 crew. She was ordered to sail south of her normal route as a precaution against possible attack. After the outbreak of war announcement of 3 September the crew were busy painting over portholes and rigging blackout curtains, and extra lookouts were posted. As tensions rose the famous comedian Bob Hope gave a special concert to help calm his fellow passengers. Queen Mary arrived safely at New York on 5 September where she was ordered to stay put for the foreseeable future, alongside her rival Normandie which suffered a similar fate. Queen Elizabeth left her fitting-out berth on 22 February 1940; with a reduced steaming crew of about 400, she had been stripped of 24 lifeboats to reduce draught in the shallow Clyde.

Before she left the Clyde the crew were informed that she was now proceeding on an ocean (Foreign Going) voyage and they would be required to sign new articles. Anyone who did not agree would be taken ashore, but only a handful asked to be released. Finally, on the misty morning of 2 March, filled with 6000 tons of fuel oil, unarmed and escorted by four destroyers and a squadron of fighter aircraft, Queen Elizabeth slipped away from the Clyde and rounded the top of Northern Ireland, where her escorts departed. Now on her own, under complete radio silence she was bound for New York which she made on 7 March 1940. Here she became one of the four biggest ships in the world: Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mary, Normandie and Mauretania which were all war refugees escaping the menace of the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine which could derive enormous propaganda coups if they were sunk. In New York these ships became a major sightseeing attraction.

Australian and New Zealand troops to support Britain in her hour of need

In November 1939 the decision was made that Australian and New Zealand troops would proceed overseas to assist Great Britain in its war against Germany. The Australian government proposed these forces be combined into an ANZAC Corps, as had happened in WWI, but the New Zealand government declined. However, it was agreed the troops should be sent together in the same convoys.

An advance party from New Zealand arrived in the handsome Union Steamship Company’s Awatea (also known as the Queen of the Tasman) and then boarded Strathallan with an Australian advance party sailing from Melbourne on 15 December 1939. After calls at Colombo, Bombay and Aden they reached Suez on 7 January 1940 where the combined advance party disembarked.

Later convoys were given special designations and those from Australia and New Zealand bound for the Middle East were somewhat confusingly given the acronym ‘US’ with the next troops to depart in January 1940 being US1; this continued through to November 1941 with US13. In 68 troopship lifts covered by these convoys some 134,00 Australian and 46,000 New Zealand troops were carried to Britain and the Middle East. These totals included naval, air force and medical staff.

There was now a debate raging at the highest levels as to the future of these vessels. They were considered too large for conversion to Armed Merchant Cruisers, unsuitable as troopships, and vulnerable to submarine attacks. Were they just white elephants that should be offered to the Americans? On the positive side, other than in the Atlantic, the risk was manageable. Elsewhere, given their high speed they could outrun most ships, were difficult submarine targets, and could be routed away from the normal range of enemy aircraft, but mines remained a problem. Accordingly, the decision was made to make them available as troopships. Queen Mary was the first to be painted overall in a drab Light Sea Gray, becoming known as the ‘Grey Ghost’.

Breaking out from America and making for Down Under

Antonia, another Cunard liner, arrived in New York on 18 March 1940 with 760 additional crew who transferred to Mauretania and Queen Mary. On the evening of 20 March, making use of fog and rain to hide herself in the Atlantic, Mauretania slipped quietly out of the Hudson River heading for Bermuda and thence via the Panama Canal to Honolulu and Sydney where she arrived on 14 April.

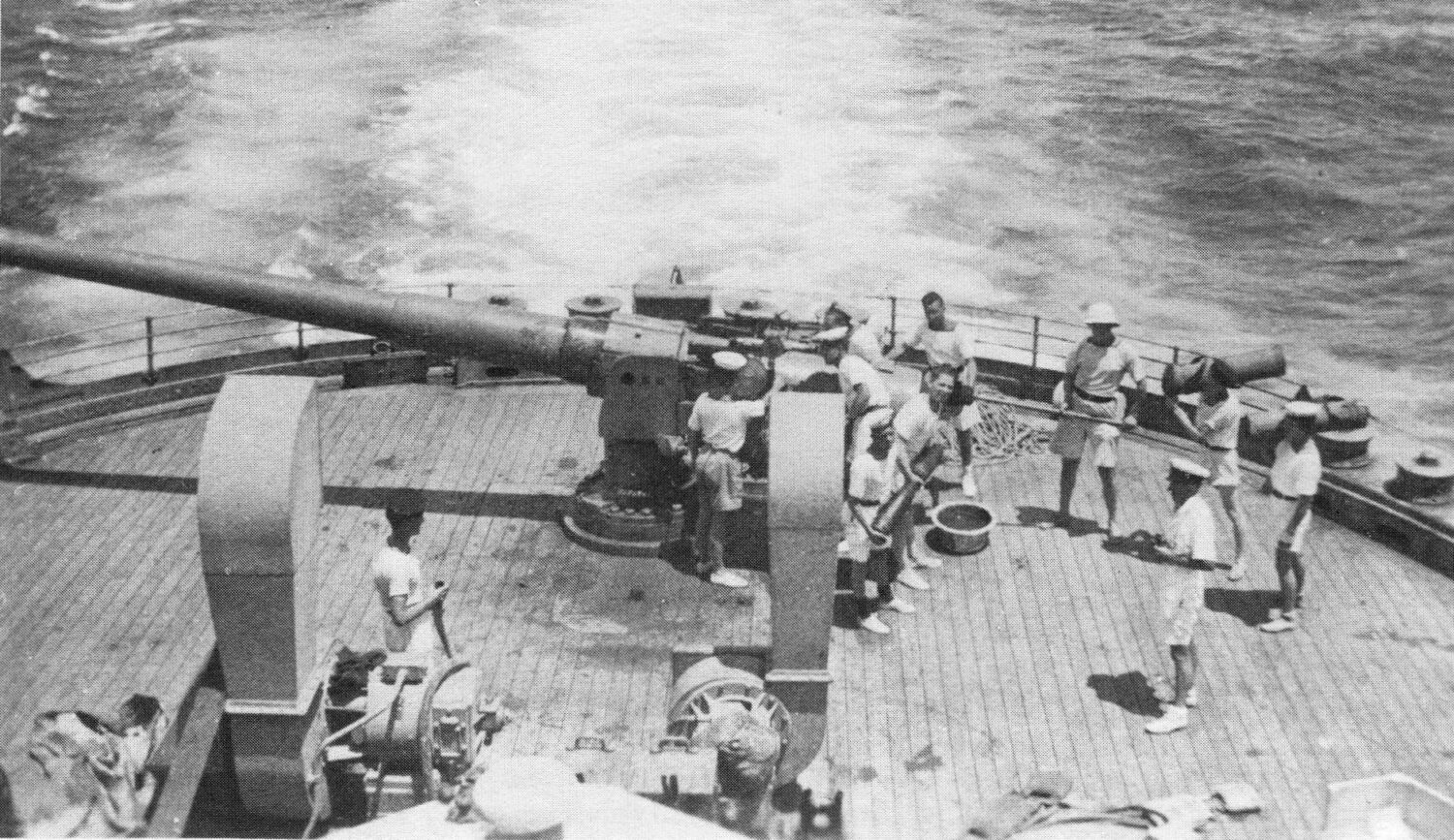

A day afterwards, on 21 March Queen Mary made her way out of the Hudson bound for Trinidad, the Cape and Fremantle and then Sydney which she reached on 16 April 1940. Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Company was engaged to rapidly refit both liners into troopships by working day and night, largely by removing furniture and fittings, placing these in store and installing bunks and hammocks, increasing amenities and generally more than doubling their carrying capacity. The ships also had armament installed. Mauretania had already been armed in Britain with 1 x 6-inch gun and 2 x 3-inch A/A guns. She had earlier been fitted out as an Armed Merchant Cruiser but was subsequently considered too large for this purpose. This was supplemented in Sydney with 4 rocket launchers, 4 x 12-pounder guns and Oerlikon machine guns. Queen Mary had also received some basic armament including a 4-inch gun. This was removed and exchanged for a vintage 6-inch gun installed at her stern and three 3-inch anti-aircraft guns and Oerlikon machine guns to provide all round coverage.

The four-funnelled liner Aquitania, another large veteran which had served as a troopship in the Dardanelles during WWI, departed Southampton on 9 March 1940 making for Freetown, the Cape and Fremantle and thence Sydney where she arrived on 10 April. She too was taken in hand by Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Company who were involved in the fitting of additional troop accommodation.

Work on all these ships was completed by 3 May 1940 in time for the departure on convoy US3 which comprised: Andes, Aquitania, Empress of Britain, Empress of Canada, Empress of Japan, Mauretania and Queen Mary.

Because of her speed, in October 1940 the Empress of Britain was allowed to return from Cape Town to Britain unescorted. On 26 October, when nearly home, on a zig-zag course just 60 miles off the Irish coast, she was sighted by a lone German Condor long-rage bomber. The aircraft flew low over the ship and dropped two incendiary bombs which exploded amidships resulting in devastating fires causing the ship to be abandoned. Thankfully one Royal Navy and one Polish destroyer and three fishing vessels rescued most of the military passengers and crew – there were just 25 deaths. As the burnt-out vessel was still afloat the next day attempts were made using salvage tugs to tow her into port, escorted by destroyers and Sunderland aircraft. But they were discovered by the submarine U-32 and in a night attack the hulk was dispatched to the deep – this was the largest ship sunk by a U-boat in WWII.

Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships

There is an interesting aside in the RAN Official War History (Gill 1957) Appendix 1 relating to DEMS which contains the following notation: Queen Mary was originally armed at Sydney (6-inch OBL) in May 1940, and an Australian DEMS gun crew was embarked. When she was transferred to the North Atlantic run, ferrying American troops to Britain, she carried a Lieutenant Commander RNVR as Gunnery Officer, a Lieutenant RNVR, and 70-odd DEMS ratings and MRA details – still with the same RANR Petty Officer who had embarked in Sydney in 1940. He left the ship in March 1943.

This refers to Petty Officer Arthur Dawn Tate who joined the ship as the gunlayer on 3 May 1940 and was discharged from her on 1 March 1943. Two other RANR sailors, W. (Wally) Taylor the trainer, and Edmund (Ted) Patrick Flynn the breech worker, had joined her on the same day.

Despite a number of other references to her early armament of a single 4-inch gun supplemented by machine guns, it appears that the 4-inch gun was removed in Sydney and replaced by a 6-inch gun in May 1940. The War Diary for Spectacle Island (Sydney Armament Depot) also contains a note regarding work performed on DEMS ships which reads: Queen Mary low angle gun exchanged. At this time Spectacle Island held an ‘Imperial Stock’ of guns and ammunition on behalf of the Royal Navy which included three 6-inch BL Mk VII guns which would be the likely source. It is not known how often the main 6-inch armament was used in DEMS ships but the important anti-aircraft guns were exercised regularly as on every US convoy the ships carried out high angle firings at kite targets towed by the escorting cruisers.

The ‘US’ Convoys

From previous experience with convoy US1 and now with bigger and faster ships, the second convoy from Australia to the Middle East was divided into two groups, US2 comprising five slower ships and US3 of seven faster vessels. US2 departed Melbourne on 15 April 1940 and proceeded via Fremantle, Colombo, Aden and Suez, which was reached on 18 May.

US3 started from Lyttelton and Wellington before coming to Sydney and Melbourne with a total of 18,200 troops embarked. The convoy reached Fremantle on 10 May 1940 after which course was made for Colombo, but while off the Western Australian coast news was received of possible mining of the Red Sea making conditions hazardous. Accordingly, the convoy was diverted via the Cape with the eventual destination drastically changed from the Middle East to Europe. However, Chinese crews manning the Empress of Japan and Empress of Canada refused to take the ships into the European war zone. The dissatisfied Chinese were placed aboard the Empress of Japan and her troops divided amongst other ships, and the Empress of Japan sailed to Hong Kong. Without her Chinese crew members, the Empress of Canada called for volunteers amongst the troops to help man the ship and this was achieved.

Plowman (2003) provides further detail of Queen Mary leaving Sydney on 5 May 1940: As the great liner steamed slowly down the harbour, there were still Cockatoo Dockyard workmen on board frantically trying to complete the fitting of the lone 6-inch gun, of 1902 vintage, which needed to be bolted in place at the stern. The job was completed just before the liner passed through Sydney Heads and the dock workers left the ship on the pilot boat. Detailed to the ship as gunners were three Australian naval ratings: Arthur Tate, Wally Taylor and Ted Flynn, who would remain with Queen Mary for the next three years.

After leaving Freetown the ships were placed on a war footing with extra lookouts posted, armament fully manned, ships carrying out zig-zag courses and additional escorts provided, including Sunderland flying boats. As they approached the Bay of Biscay the now six troopships were escorted by a dozen warships including the battlecruiser HMS Hood, the largest ship in the Royal Navy. The convoy arrived safely off Gourock, at the mouth of the Clyde, on 16 June 1940, after a voyage of 43 days. This was at the Mother Country’s darkest hour when a German invasion was expected and the additional Commonwealth troops were most welcome. On 18 June Prime Minister Winston Churchill made a broadcast announcing that a German invasion of Britain was imminent and on 20 June Churchill again sounded a warning of an imminent invasion. It was to be some time before these Aussie troops in England met up again with their fellow countrymen in the Middle East.

Queen Mary remained at Gourock until 29 June 1940 when she loaded 5000 British troops bound for the Cape where they transferred to other vessels to complete their voyage to the Middle East. Queen Mary then made for Trincomalee and Singapore arriving on 4 August 1940. Here she entered the King George VI drydock, and was fitted with degaussing coils and paravanes. She undocked on 16 September and two days later travelled alone and unescorted at an average speed of 27.75 knots making for Sydney, where she arrived on 24 September 1940.

With so much activity and change to programmes there were no convoys from New Zealand and Australia in June and July 1940 and Queen Mary was unavailable to participate in convoys US4 and US5.

Malaya and Singapore

In December 1940 the Australian government had expressed concerns about the adequacy of defence of the Malay Peninsula and advised Imperial authorities that it would be prepared to provide support.

This led to the secret undertaking of Queen Mary being made available to transport the 8th Division Headquarters and the 22nd Division, comprising 5718 men, to Singapore. Accordingly, on 4 February 1941 Queen Mary and Aquitaniadeparted Sydney, linking up with Nieuw Amsterdam outside the Heads. Escorted by HMAS Hobart the troopships headed south where Mauretania, which had sailed from Melbourne, joined them in Bass Strait making for Fremantle. When clear of Fremantle the troops aboard Queen Mary were informed that they were no longer bound for Ceylon and the Middle East but were going to Singapore. They were not pleased with this news as there was a great difference in prestige between going to war than sitting around doing garrison duty. Little did they know that they would shortly meet some determined Japanese.

Queen Mary had left the remainder of the convoy and escorted by the light cruiser HMS Durban made for Singapore which was reached on 18 February. Here Queen Mary disembarked the first contingent of Australian troops to reach Singapore and then drydocked in the graving dock recently vacated by Queen Elizabeth. Some much-needed maintenance was undertaken and on completion she returned to Sydney, arriving on 1 April 1941. A week later she recommenced her regular convoy run to Trincomalee and thence Suez making a total of seven further voyages.

Queen Elizabeth enters the fray

We may recall Queen Elizabeth first entered the Hudson River on 7 March 1940 and much like Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner she lay ‘as idle as a painted ship’ for over eight months. With America nominally neutral no major work could be undertaken, although some interior services to electrical and ventilation were completed. It was not until late November 1940 that arrangements had been made for Queen Elizabeth to depart New York. She headed to Cape Town for fuel and reached Singapore on 13 December 1940 where she entered the dry dock and at long last the launching blocks which were still attached from her days in the Clyde were removed. Major work was now undertaken in completion of fittings, installation of degaussing and she was armed with a 6-inch, circa 1908 gun on her after deck, as well as 3-inch AA guns, one on each quarter and another amidships. She left Singapore on 11 February 1941 escorted by HMS Durban and other than a short two days at Fremantle was routed, unescorted, south of Tasmania at a speed of 25 knots, arriving in Sydney on 21 February 1941.

It looked as if almost half the population of Sydney came out to line the harbour and book passage on ferries to catch a glimpse of this famous ship. With insufficient berths, a problem still with us over 80 years later, she was obliged to moor off Athol Bight. Here the Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Company was engaged to complete her fit-out as a troopship. Some of her furniture was taken ashore for storage, then bunks were fitted to double her accommodation to cater for about 5500; dining rooms, bathrooms and hospital facilities were all increased.

It was time for both the Queens to operate together. Queen Mary was already in Sydney and on 8 April 1941 embarked 6000 troops as she lay anchored off Bradleys Head. Next morning Queen Mary raised anchor and passed through Sydney Heads at the same time Queen Elizabeth was approaching from the south and so it was that off Sydney Heads that these two great liners passed at sea for the first time. Queen Elizabeth then took her sister’s berth and anchored off Bradleys Head where she began boarding her first contingent of 5333 troops. On the morning of 11 April Queen Elizabeth raised anchor and departed on her first trooping voyage being followed down harbour by Ile de France (now flying British colours), Mauretania and Nieuw Amsterdam. A few hours later off Jervis Bay the four liners met with Queen Mary.

This mighty convoy must have made a magnificent sight as they steamed down the eastern seaboard led by HMAS Australia in the van, with Queen Mary leading the starboard column, Queen Elizabeth leading the centre column, and Mauretania the port column. The columns were 1000 yards apart and the ships following in column were at 800 yard intervals. Ile de France followed Queen Mary and Nieuw Amsterdam followed Queen Elizabeth, all proceeding at 19 knots. After leaving Fremantle on 22 April the convoy was reduced when Nieuw Amsterdam changed course and headed alone for Singapore with more reinforcements, while a New Zealand contingent in Singapore was transferred to Aquitaniaand joined up with the remainder of the convoy in Colombo. The ‘Queens’ went to Trincomalee and thence made for Suez; during this time a distress call was received from a British freighter which was being attacked by the German raider Pinguin. Unable to offer assistance, the two liners and their escort HMAS Canberra raced for Suez.

Their destination was Port Tewfik near the southern entrance to the Canal; as the port was crowded it could not accommodate both Queens at the same time with Queen Mary berthing first on 3 May and Queen Elizabeth slowing down to berth three days later. The ships could only disembark troops during daylight as the port was attacked by German bombers at night. When her troops were safely ashore Queen Mary embarked German and Italian POWs, after which both Queens linked up again and made for Trincomalee, arriving on 14 May. From here Queen Mary returned to Sydney arriving on 25 May and Queen Elizabeth proceeded to Singapore for drydocking and was back in Sydney on 14 June 1941.

The Final US Convoy

The final US convoy US13 involving the two Queens started on 31 October 1941 when Queen Mary with 5000 troops embarked (including 200 Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses), made for Jervis Bay allowing her sister to enter harbour and take aboard a further 4500 troops on 2 November. The Queens met up again off Jervis Bay and, escorted by HMAS Canberra, plied the well-worn course of Fremantle, Trincomalee and Suez which was reached on 22 November. Queen Mary anchored first and disembarked her troops followed by Queen Elizabeth which afterwards embarked a large number of German and Italian POWs. The two liners next made for Trincomalee where it was planned that they would go separate ways, Queen Mary to Singapore for drydocking and Queen Elizabeth directly to Sydney.

At this time HMAS Sydney, then operating in the southern reaches of the Indian Ocean, was overdue and it was later discovered she had been sunk with the loss of all her crew by the German raider Kormoran. This became clear when on passage from Singapore to Sydney on 24 November, Aquitania picked up a life-raft with 24 German survivors from Kormoran. With this tragedy and Japan’s entry into the war, grave concerns were held for the safety of the Queens. It was however decided Queen Elizabeth should continue her voyage to Sydney which was reached on 16 December. The risk of Queen Mary continuing to Singapore was considered too great and after some time at Trincomalee she made for the Cape, Trinidad and New York where she arrived on 12 January 1942.

Two weeks later the liner made the short trip to Boston where she drydocked for a major overhaul. Afterwards on 18 February Queen Mary sailed with 8398 American troops and a crew of 905, at this time a record for the number of persons embarked on a single ship. Her crew now included about 100 gunners to man her armament, which included five Bofors guns. They were bound for Trinidad for fuel but owing to increased U-boat activity with ships sunk off Trinidad this was cancelled and she anchored off Key West where fuel was brought out in tankers. She next made for Rio de Janeiro, then across the South Atlantic to Cape Town where she took on extra passengers, General Sir Thomas and Lady Blamey. General Blamey had commanded Australian troops in the Middle East and had flown from Cairo to Cape Town on being recalled by the Australian Government. Queen Mary reached Fremantle on 23 March where General Blamey and Lady Blamey disembarked, making the final leg to Melbourne by air. Sydney was reached on 28 March with the first contingent of American troops to enter Australia making temporary camp on Randwick Racecourse. Queen Marydeparted on 6 April 1942 with only 58 passengers, returning to New York via Fremantle, the Cape and Rio.

On 7 February 1942 Queen Elizabeth sailed from Sydney via New Zealand, crossing the Pacific heading for Esquimalt in British Columbia for a much-needed docking. While in Canada Queen Elizabeth’s troop-carrying capacity had been dramatically increased, and on 10 March 1942 she left Esquimalt for San Francisco with 8000 American troops bound for Australia. Accompanying her were two American liners Mariposa and President Coolidge, both carrying troops for New Zealand which were escorted by the cruiser USS Chester.

Queen Elizabeth arrived in Sydney on 6 April, passing her outbound sister off the Heads. Queen Elizabeth remained in Sydney until 19 April when she departed for Fremantle, the Cape and Rio arriving at New York on 24 May. A week later she was again on her way, this time carrying 10,000 American troops on the relatively short passage to Europe.

Because of their importance to the war effort, der Führer offered a bounty of one million reichsmarks and Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross (Germany’s highest military honour) to any U-boat captain that sank either of the Queens.

In their new roles both Queens were now mainly employed taking US troops across the Atlantic, seemingly with ever increased capacity. The record for troops carried goes to Queen Mary with 15,740 troops plus 943 crew aboard in July 1943; this total of 16,683 remains today the largest number of persons carried by a single ship. Overall she carried a staggering 765,429 military personnel during the war. Her American interlude was interrupted in early 1943 when the AIF 9th Division of 30,000 troops was brought back from the Middle East under Operation Pamphlet which included Queen Mary, Aquitania, Ile de France, Nieuw Amsterdam and the AMC Queen of Bermuda with a heavy escort, arriving Fremantle 18 February and reaching Sydney on 27 February 1943.

The Quiet Australian

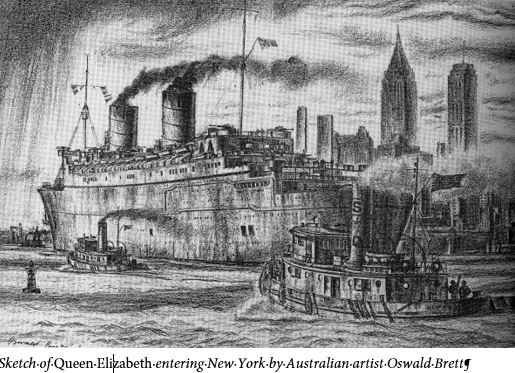

Oswald Brett (1921-2017) was born in the Sydney suburb of Cheltenham. His love of art was inspired by his mother, a talented amateur artist, and his mentor and lifelong friend John Allcott. This interest resulted in him spending much of his youth sketching ships in Sydney Harbour. To the displeasure of his father, who had served as an Army officer in WWI, the youngster failed high school, but for a time attended an art college. At just 18 years of age he signed on as an Ordinary Seaman in the Burns Philip ship Malaita, off to romantic adventures in the South Seas.

With the advent of WWII and the mighty Queen Elizabeth coming to our shores he was able to secure a position in her. Here he sketched on-board scenes capturing everyday activities, which were reproduced by Konings (1985). While mainly plying between the Clyde and New York he was able to spend some time in the fabulous museums and galleries in the great city and it was here he met fashion designer Gertrude Steacey. In 1944 they married and eventually settled in New York, raising two children. Oswald established himself as a highly regarded maritime artist. His works are held by the Australian War Memorial, the US Naval Academy, the White House and in maritime museums in Australia and overseas.

Summary

Of all the major Australian troop movements of the war, those involving the US convoys were by far the most extensive. The 13 US convoys transported 134,000 Australian and 46,000 New Zealand troops to the Middle East and Britain, while a further 14,000 Australian troops were carried to Singapore.

The above figures also include a relatively smaller number of RAAF, RAN and medical personnel. Winston Churchill, who travelled three times in the Queens whilst visiting the United States during his period as wartime prime minister, perhaps best summarised the continued importance of these ships when he wrote: Built for the arts of peace and to link the Old World with the New the Queens challenged the fury of Hitlerism in the Battle of the Atlantic. Without this aid, the day of the final victory must unquestionably have been postponed.

References

Bissett, James, (Sir), Commodore – War, Peace & Big Ships, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961.

Gill, G. Hermon, Australia in the War of 1939 -1945, Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1957.

Konings, Chris, Queen Elizabeth at War, Patrick Stephens Ltd, Baldock, Herts, UK, 1985.

Marcus, Alex, DEMS? What’s DEMS? Boolarong Publications, Brisbane, 1986.

Plowman, Peter, Across the Sea to War, Rosenberg Publishing, Sydney, 2003.

Jeremy, John, Cockatoo Island – Sydney’s Historic Dockyard, UNSW Press, Sydney, 1998.