- Author

- Minto, Thomas, MN, Captain

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2002 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

A Young Boy’s Options

In 1922 I was 15 years of age and wondering what life held for me in the way of a career. Queensland at that time was the nearest thing to a Socialist State ever achieved in Australia. We had State Fish and Chips Shops, State Butchers Shops competing with local tradesmen, not very well, I might add.

I was at the Technical College and had filled in the forms as to Preferred Trade. My choice was first Fitter and Turner, second Motor Mechanic. When my turn came, I appeared before the Apprenticeship Committee. Choice 1 – No Vacancies; Choice 2 – No Vacancies. You are to report next Monday morning to Sachs the Plumbers. I replied that “I did not want to be a plumber.” They responded. “The decision is yours. You now go to the bottom of the list”. Exit Thomas Minto.

Commonwealth Apprenticeships

It was then that my Mother read in the newspaper that the Federal Government was offering an apprenticeship in the Commonwealth Government Line of steamers to one boy from each State, but the boy must be a Deceased Soldier’s son. I applied and was called in for an interview.

As I boarded the tram on my way home, I saw my mother sitting on a seat some distance away. She looked at me inquiringly. I nodded, and to my great surprise, she burst into tears. Such an outward display of emotion by a Scot was unheard of. It was then I realised that I WAS LEAVING MY HOME AND MY FAMILY. I felt like crying too, until I pictured my four older brothers passing judgement. That stiffened up the sinews!

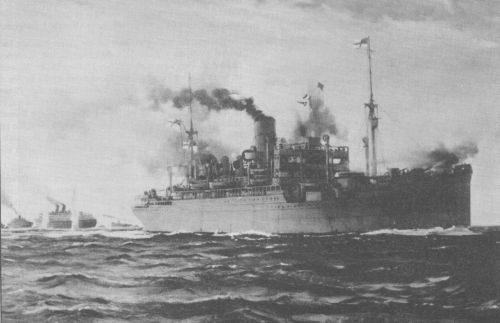

On the 22nd November 1922 I went to sea. Not in a sailing ship, not in a poorly equipped Cargo Steamer. It was the Jervis Bay, a passenger and cargo vessel.

Built in Barrow on Furness, she was on her Maiden Voyage. The Master was Chaplin, the Chief Mate Laycock, and the Chief Engineer was Jock Bell.

There I met the boys from other States; Roy Hendy from Sydney, Albert Judge from Melbourne, Stan Bonney from Adelaide, John Adams from Perth. Peter Murdoch from Tasmania had been posted to another vessel.

The Repatriation Department had fitted us all out with our uniforms, shirts, working clothes, and heavy weather gear. My first pair of long trousers! The West Australian boy was so small his double breasted jacket had only room for six buttons instead of the regulation eight.

Adams was the only one who did not stay the distance. A very clever boy, he was a complete misfit as far as seafaring was concerned. He gave it away in less than a year. The rest of us carried on and in due course we all passed for our Master’s Certificate.

The Working Day

The Jervis Bay was on the England to Australia trade. We carried passengers but our contract with them was minimal. I am still in touch with one family, however, the Baltzers. Our day started at 0600 when we hand scrubbed the Bridge and the Lower Bridge teakwood decks. The rest of the day was holystoning decks, cleaning brasswork, washing paintwork and painting winches. It was constant.

The Baggage Master was Alex Kemp. He had been a Chief Yeoman of Signals in the Royal Navy. You cannot go higher without a Commission. We reckoned he thought in Morse Code and spoke in Semaphore. Each day at sea, from 11.20 to noon, he taught us Semaphore and the International of Signals. (Each letter of the alphabet has its own flag). From 8 to 8.30 pm we did Morse Code on the lamp. As a result we received training in Signals which exceeded by far the normal standards of the Merchant Service. For the rest of my seafaring career I could more than hold my own with any of the Ship’s Company. This proved very useful in World War II convoys.

At 3.45 pm we ceased work and cleaned up, then reported to the Lower Bridge at 4 pm for Seamanship Lessons, such as the Rule of the Road at Sea, from the 4th Mate. At 5.45 pm the 1st Mate took over and gave us our Home Work.