- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2012 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Ron Robb

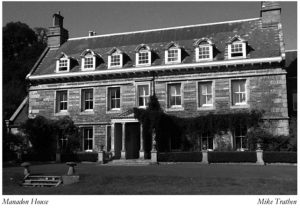

Most engineering officers serving in the RAN have at some time or other studied in HMS Thunderer, the Royal Naval Engineering College at Plymouth in England. Ex-students usually refer to the establishment as Manadon, the original name of the old estate on which the college now stands. The Captain’s house, still known as Manadon House, is now over 300 years old and was the manor house for the estate; it ranks as one of the most attractive Commanding Officer’s residences in any military establishment anywhere. The year 1980 marked the college’s centenary – although it was not always on the present site and was not always known as Manadon.

This article by LCDR R.K. Robb, RAN, a member of the RAN Historical Society, appeared in Navy News of 22 August 1980 and gives a brief background history of the present college. To set the scene it is appropriate to be aware of events which gave rise to the need for such a place. Minor amendments bring the article up to date.

The Royal Navy Engineering Branch – from which the Royal Australian Naval Technical Services are directly derived – trace their origins back to the early 19th century when civilian engineers went to sea with the new-fangled steam ships, which many believed were merely a passing experimental phase. Even as late as about 1890 the Admiralty’s official line on electrical power was that, apart from incandescent lighting and gun firing, no use was likely to be found for it in HM Ships. Indeed a dedicated electrical engineering branch was not formed until 1946.

In 1834 Commander Robert Otway warned that: …the Navy must select men of education and scientific acquirements for the service of Her Majesty’s steamers. Engineers became part of the Navy in 1837, being granted the rank of Warrant Officer at that time. Ten years later they were granted full commissions but only under some sufferance because they were still little more than mechanics and greasers – hardly fit occupants for wardrooms of the day. Even so, when the non-commissioned engineering rating was introduced to handle the more mundane technical tasks it was most bitterly resisted by the engineering officers as a usurpation of their function. However, despite all this consolidation and expansion, engineers’ training and formal education was something less than satisfactory during the early part of the 19th century.

Various sites were considered for the setting up of a proper engineering school, but many years were to pass and a number of interim arrangements made before the present RNEC emerged. One of the first places suggested during the 1830s was an unfinished edifice intended for royalty; conveniently near the Admiralty, in the St James area, it was at that stage known as ‘Buckingham House’. Eventually, in 1843 the barque Sulphur was allocated as accommodation at Woolwich for engineer boys under training and those lads became the first identifiable career engineer officers with formal tertiary training for the RN Engineering Branch. They were trained as civilian boys and were not commissioned until completion of their technical education.

In 1863 the Royal School of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering was established at Kensington (the site is now occupied by the Victoria and Albert Museum). Its standard was very high and gave notice that the Navy was seriously in the business of advanced tertiary technical training, but it lasted only ten years, for in 1873 it joined forces with the Portsmouth Naval University in the old Royal Palace at Greenwich. The engineering qualification issued there post 1873 was highly regarded and about equivalent to a Cambridge honours degree. Greenwich is still used for the Navy’s higher education, (especially for nuclear engineering) and RAN officers also study there, principally as members of the Staff Course and as ab initio Special Duties List training.

For one reason or another, all these venues had shortcomings as an engineering university for the Navy, so by July 1880 a new centre had been constructed at the Plymouth Dockyard. This became known as Keyham and it was here that RAN students came into the picture. Keyham was the first permanent home for an engineering college and is still used for Dockyard training today.

In those days students entered as midshipmen between the ages of 14-17 years, and went straight into the engineering college. Later, they first joined all other midshipmen at Dartmouth and prior to the First World War all officers, regardless of specialisation, were trained to ultimately command HM Ships. This philosophy continued into the 1920s. By 1936 it was evident that Keyham was becoming too cramped for its intended function. Two major factors contributing to this were the rise of the aeronautical and ordnance engineering sub-specialisations.

New property was sought near to Keyham and the Admiralty purchased a 100 acre estate based on Manadon House, which became the first wardroom. Part of it was also converted to flats for the Captain and some staff officers. By 1941, shortly after the start of the Second World War, some new buildings were ready for occupancy, so Manadon gradually began to take over the Keyham functions. However, it was to be twenty years before the transfer was complete. Today, RNEC Manadon is a fully accredited degree issuing institution (it had previously taken its degrees and diplomas ex London University) and some post graduate training is also offered. The college provides an environment where the traditional academic, sporting and cultural activities take place alongside ‘divvies’ and sword drill.

College records are not perfectly clear as to who the first RAN students were. However, Lieutenant (E) E.S. Nurse is the first identifiable Australian on the records – he graduated in April 1919. The next RAN officers appear in the August 1923 graduating list: D. Aitken, A. Cairns, D. Clark, K. Dudley, S. Hodgson, O. McMahon, R. Rowlands, R. Spencer and E. Wackett. Perhaps the best known of the early RAN engineers came a couple of years later: K. McKenzie Urquhart. His name still stands in the college as a notable sportsman and years later he became the Third Naval Member of the RAN Board, a post which continues today as Chief of Naval Technical Services.

There are still several senior RAN engineers around who served under K. McKenzie Urquhart. All these officers linked up as midshipmen with their RN counterparts at Dartmouth after initial training at the RAN College, and during WW II, many went straight into Royal Navy ships after Manadon. They did not return to Australia for some years, so strong was the Dominion affiliation with the ‘Old Country’.

The strength of these Empire links can be gauged not only by the fact that many RAN officers served in RN ships for considerable periods, but also by noting that the first recorded ‘foreign’ students at Manadon were four Poles who escaped overland through Europe and joined the college in 1940. Australian, Canadian and New Zealand officers were part of the British family and during WW II their food parcels added welcome relief to the spartan rations of wartime college fare. Records indicate that the Canadians were the best supplied! These family ties were further reflected at the college’s centenary engineering conference and dinner on 2 May 1980, for, despite the high number of Royal Navy serving and retired engineering officers (some now very old men, who had been to Keyham shortly after it started) the college graciously offered places to the three Dominion navies.

Due to an overwhelming response, the college authorities had some unpleasant hatchet work to do on the attendance applications, but with some fancy foot-work by CMDR Bob Nattey of ANRUK Staff, the RAN had the largest non-RN representation and the seven RAN officers who attended were conscious that they were representing a long line of serving and retired engineer officers of all branches and lists.

Rear Admiral Bennett, CNTS for the RAN, sent the following signal which was read to all the assembled guests:

On behalf of the RAN Engineer Officers who have been privileged to study at the Royal Naval Engineering College during the last sixty years, it is my great pleasure to send you hearty congratulations upon your first centenary.

The foundations of sound naval engineering in this and many other navies have been well and truly laid at Keyham and Manadon.

I much regret my inability to attend but feel well represented by two of my predecessors plus several serving RAN officers who will be with you to join in the events honouring past achievements. I believe it is fitting that the challenge of preparing naval engineering officers for the future is the theme of your centenary conference.

Many of the problems highlighted in the programme have a very familiar ring because they are largely RAN problems also.

Quite apart from the nostalgic ties of the past I feel that this fact will provide the strongest reason for continued close association during the second century of the RNEC.

Wishing you all success for the future.

Vice Admiral Stevenson, RCN, Rtd, delivered a centenary greeting on behalf of all Dominion engineering officers, and the RNZN also sent a greeting and held a concurrent commemorative dinner.

The conference and dinner were presided over by the Chief Naval Engineer Officer, Vice Admiral Lindsay Bryson. Guest of honour at the dinner was the Chief of the UK Defence Staff, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Terrence Lewin.

The Second Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Desmond Cassidi, also attended. Amongst nearly 400 guests they, along with the Chaplain, were among the very few non-engineers present.

In his speech, Sir Terrance Lewin injected a sober warning that the present unstable world situation places grave challenges before naval engineers, and Vice Admiral Bryson reminded his professional colleagues that while they have every right to be proud of their traditions they are part of a ship’s team where lines of demarcation are becoming increasingly blurred. In this respect it is interesting to note that the first RN executive branch officer will this year join Manadon for engineering degree training, and the pattern of change within the Engineering Branch is already underway with the introduction of a combined Electrical/Mechanical Degree.

RAN Engineering Officers are not at present undertaking degree training at Manadon but arrive there already qualified, ready to take part in specialist application courses. Special Duties List officers study to the Technician Engineer level (or as it is called in Australia, Associate Engineer). The average number of RAN officers who pass through Manadon each year is about fifteen. Such training is expensive, but it pays off over the years in ways that are not easily quantifiable. One particular benefit is that RAN engineering officers serving at overseas posts or undertaking study and investigative tours are able to tap into the ‘old school network’ in a way no officialdom can, for Manadon students come from all round the world and friendships made while studying at RNEC last a lifetime. The accompanying photograph shows the RAN contingent to the centenary conference and dinner. Many guests were impressed by the fact that three of the Australian officers present had flown to the UK at their own expense to meet their old contemporaries and represent past RAN students.

Footnote:

Acknowledgement for permission to use many of the historical notes in the preceding article is gratefully given to Captain P. G. Hammersly, RN, Commanding Officer of HMS Thunderer, and also to Lieutenant Commander R. Nichol, RN, who researched the college’s recently published short history: RNEC 1880 to 1980.

While HMS Thunderer produced about 150 engineering officer graduates a year it became subject to a rationalisation of training facilities and in 1994 it was de-commissioned when Royal Naval engineering officer training was transferred to Southampton University.

The grounds of Manadon House were sold off for redevelopment but the grand residence remains, being used as a function centre.