- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - pre-Federation, Influential People

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

The English Civil War

During the 18th and 19th centuries the name Enderby was well-known in shipping circles in Great Britain and its colonies in America and Australia but is now largely forgotten. This Puritan family with its roots in rural Lincolnshire first came to notice with financial assistance to the Cromwellian cause during the English Civil Wars (1642–1651). They were rewarded with land grants but largely sold these in favour of other business interests.

During the 1600s the Enderby family had tannery and cooperage businesses on the banks of the Thames at Bermondsey, and this was near where the Great Fire of London started in a bakery on Pudding Lane in 1666, when most of old London was destroyed. Having suffered enough, they moved down river to more fashionable and less dangerous Greenwich where they established a rope and canvas works.

Shipping and Whaling and another Civil War

Samuel Enderby ventured into shipping in the 1760s which expanded into a successful enterprise carrying mixed goods to the American colonies and returning to England with lucrative cargoes of whale oil, caught by the American colonial whaling fleets. Three whaling ships, Beaver, Dartmouth and Eleanor, were chartered to the East India Company, with return cargoes of tea. They were involved in the fateful ‘Boston Tea Party’ in December 1773. Samuel’s 16-year-old daughter Mary was aboard Beaver during this incident when colonists disguised as native Red Indians seized a cargo of tea which they poured into the harbour in objection to high rates of taxation imposed by the Imperial authorities. Two years later the British Government placed an embargo on the export of whale oil from New England, giving rise to the American War of Independence (1775-1783) and ruining the trade.

James Cook’s Endeavour was fitted out on the Thames at Deptford, and given his own interests in exploration it is very likely that Samuel Enderby would have been aware of this expedition. Following Cook’s discoveries which mentioned that the southern seas were full of whales and seals, the Enderbys saw a potential business opportunity. Accordingly, in 1775 they encouraged American associates to assemble a fleet of sixteen whaling ships, all commanded by experienced American loyalists supporting the Crown.

The timing of this whaling expedition into southern waters was inopportune. Regarded as Revolutionists, they were pursued by a Royal Naval squadron with five ships captured and impounded and their crews pressed into naval service. Samuel Enderby negotiated with British authorities on behalf of the owners, resulting in the vessels and their crews eventually being released. The Enderbys cultivated important political contacts which included the long serving Prime Minister William Pitt (the younger) until his death in 1806.

In 1786 the Enderbys lobbied the government for the right to trade to the South Pacific, a monopoly enjoyed by the East India Company. They were successful and on 1 September 1788 their 270-ton whaler Amelia (the ship was registered as Emilia but is most often known by the former name), departed from the Downs for Cape Horn and the Pacific. She returned with a cargo of sperm whale oil, marking the beginning of a new era for the company, with many others following in Amelia’s wake.

With the potential loss of the American colonies, the transportation of felons to them ceased, calling for new initiatives. This gave rise to the use of convict labour in colonising New South Wales. Again the Enderbys spied an opportunity. Could not their ships transport convicts and stores to the new colony and on their return exploit whaling resources? The Enderbys by now had a fleet of 68 vessels and five of these, Active, Britannia, Mary Ann, Matilda and William & Ann,joined the third fleet in 1790 taking convicts to New South Wales.

The story of the pioneering whaling attempts by the five Enderby vessels in the establishment of a southern fishery was cemented in 1791 with the establishment of an office in Port Jackson to complement their whaling and transportation operations. Their first cruise was largely unsuccessful, not from a lack of whales but from gale force winds preventing them lowering boats. As a result, they all sought shelter including at Jervis Bay upon which they reported favourably. It did not take long to expand their efforts with frequent whaling voyages being made from Port Jackson and an abundant harvest being found around the shores of Van Diemen’s Land.

Following Britannia’s outward voyage, she was due to return via China for a cargo of tea and then to head to England. But first Captain Raven of Britannia tried his hand at whaling and caught the first whale off the Australian coast on 10 November 1791. The ship was then chartered by officers of the New South Wales Corps to proceed to the Cape of Good Hope for additional supplies. With prevailing winds this involved a lengthy east-about passage south of New Zealand. Britannia called at Dusky Sound for wood and finding the region teeming with seals left behind a party to harvest the skins and oil knowing that a ready market existed in China.

Colonising and Shipbuilding

The ‘Enterprising Enderbys’ Dusky Sound party started the first European settlement in New Zealand. These volunteers were led by Britannia’s second mate William Leith and included a carpenter. They were left with stores to last 12 months with instructions to build accommodation, and a small vessel in case relief did not arrive. Britannia returned 10 months later and took the party off, together with 4,500 seal skins and a quantity of oil. A partly completed vessel was left on the stocks.

Two years later two ships, Endeavour1 (not Cook’s ship) and Fancy trading from India were in Sydney Cove ready for their return voyage. With winds taking them towards New Zealand and Endeavour leaking badly they made for Dusky Sound. To confuse matters the ships were found to have 46 stowaway convicts aboard. On reaching the Sound Endeavour was condemned and the survivors completed the vessel left behind by the sealers, naming her Providence. She was the first major vessel built in Australasia, mostly of spruce (rimu). With insufficient space to accommodate all survivors a further vessel Resource was built, mainly from Endeavour’s longboat. Two vessels made for Norfolk Island but the smaller Resource for Sydney. However, 35 had to remain behind and were not finally rescued until 1797.

The company’s influence possibly reached its zenith in 1793 when the Enderbys provided a ship to the Royal Navy, HMS Rattler, commanded by Lieutenant James Colnett, to survey whaling grounds in the South Pacific. Shortly after Rattler’s return Samuel Enderby died and was succeeded by his three sons Charles, Samuel and George.

A Change of Guard

By the 1790s the business was a partnership between three brothers, Charles, Samuel and George, although Samuel (junior) was the driving force. Pursuing business, the Enderbys developed friendly relationships with early colonial governors, especially the third Governor of New South Wales, Philip Gidley King (1800-1806). King’s children, educated in England, lodged with the Enderbys at Greenwich.

The brothers were fascinated by science and geography and were founding members of the Royal Geographical Society. They often turned their whaling expeditions into voyages of discovery which indirectly provided Australia and New Zealand greater access to Antarctica but adversely affected their profitability. Discoveries made by Enderby ships included the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands, and the Antarctic regions of Liverpool Island, Graham Land and Enderby Land, vast areas which they named and claimed for the Crown. Further names associated with Enderbys are the Sabrina Coast and Balleny Corridor used by the great explorers Scott, Shackleton, Amundsen and Byrd. Today the same route is used by ships supplying McMurdo Station (United States) the largest Antarctic station, and the nearby Ross Base (New Zealand).

Of this generation, Charles died in 1819 and Samuel and George both died in 1829. They were replaced by another generation of Samuel (junior’s) sons – Charles, Henry and George. An older brother Samuel opted out of the family business and initially entered the Royal Navy as a Volunteer; he was promoted Midshipman while serving in the 74-gun HMS Defence at Trafalgar. Subsequently he purchased a commission in the 5th Dragoon Guards based in India. He retired from Army service as a captain and died in 1873.

The most remarkable of Samuel (junior’s) children was his daughter Elizabeth who married Henry William Gordon, an Artillery man, and they were to have eleven children. All the boys followed their father into distinguished military careers, the most famous being Charles George Gordon, better known as Gordon of Khartoum. He became a national hero when he gave his life to save a besieged garrison.

Antipodean Adventurers

In 1830 the Enderbys sponsored an Antarctic expedition under the command of John Briscoe in the 157-ton brig Tula (rigged for whaling) accompanied by the small 49-ton cutter Lively which they had purpose-built for exploration. This expedition set out from Gravesend on 14 July 1830 and made for the southern waters calling at the Falkland Islands (recently colonised by Britain). Wintering in Hobart they circumnavigated Antarctica where Briscoe discovered Enderby Land, Graham Land and Queen Adelaide Island, taking possession in the name of the king. They also visited the Bay of Islands in New Zealand, and the Chatham1 and Bounty Islands. On their return, while searching for whales Lively was wrecked on the Falklands but her crew was rescued by another vessel. The Briscoe expedition returned to England on 31 January 1833.

Charles remained fascinated with Australia and New Zealand and the remote southern islands which his father’s captains had discovered. In the late 1830s Charles purchased shares in the Fremantle whaling Company and the Perth Whaling Company which jointly caught their first whales in 1837. In that first year of operations the export revenue to Western Australia from whaling exceeded £3,000, almost twice that of the next largest export, wool. This led to an influx of foreign, mostly American, competition and at its peak in 1845 some 300 whalers were operating off the western and southern coasts of Australia, virtually unhindered by British or colonial authorities.

In business, timing is often critical. In 1791 the company owned or leased 68 ships but by 1815, with increased American competition and the introduction of gas lighting affecting the demand for whale oil, the Enderby fleet had been reduced to just five ships. With the decline in oil the family expanded its rope, sail making and joinery businesses at Greenwich, which at their peak covered a total of 14 acres and employed 250 men. In 1845 their large, critically underinsured works burnt to the ground, placing a severe financial strain on the family businesses.

Charles was convinced that a prosperous colony servicing sailing ships in the Southern Ocean could be established in the Auckland Islands which lie about 450 miles (750 km) south of New Zealand They are a sub-Antarctic group of islands occupying about 240 square miles (625 km2) straddling the ‘Furious Fifties’ with the steep-sided islands providing shelter from gales that encircle the globe in these latitudes. They are mainly peat bogs covered with scrub and stunted rata trees which, other than for a short summer season, are beset by ferocious winds and incessant rain. The smaller Enderby Island does however possess improved pasture suitable for farming.

On 1 March 1847 the British Government granted Charles Enderby a 21-year lease over these islands at a peppercorn rent, giving him exclusive rights to operate a whaling station on them. As the Enderbys could no longer afford to directly finance such a venture a prospectus was issued seeking investors for the Southern Whale Fishing Company. The prospectus said: The Auckland Islands are exceedingly healthy and have rich virgin soil, the settlers will be free from aboriginals there being none on the island. This information is in consequence of a favourable description provided by Sir Charles Ross who commanded HMS Erebus with her consort HMS Terror on an Antarctic expedition and in November 1840 spent three weeks at Port Ross on Auckland Island, introducing sheep, poultry and rabbits. Ross recommended them as a penal settlement and whaling station.

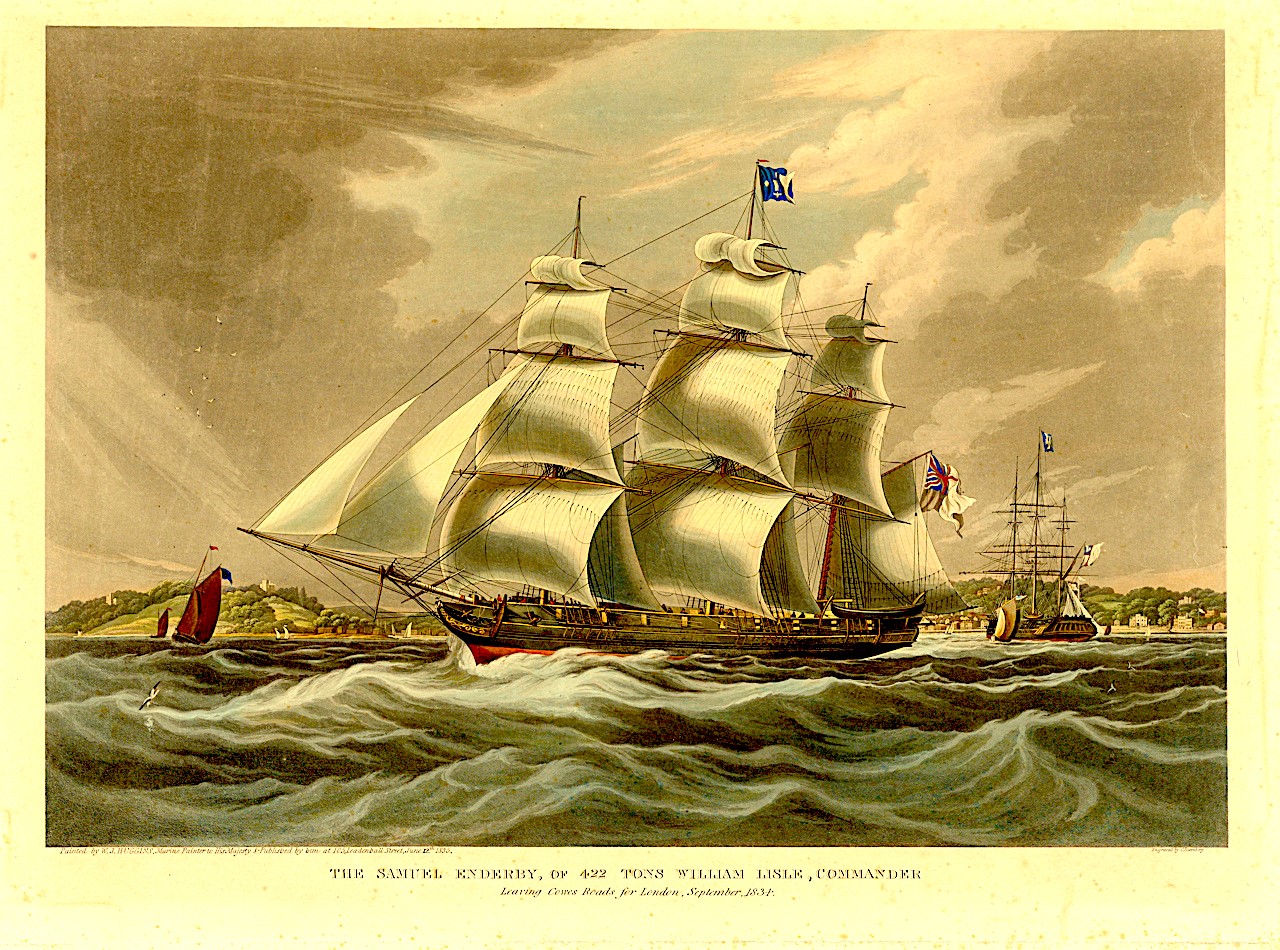

The company was formed under the chairmanship of Charles Philip Yorke, Earl of Hardwicke. Despite his inexperience Charles Enderby was nominated as Chief Commissioner of the settlement and by Royal Warrant appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the Auckland Islands. The fine 422-ton ship Samuel Enderby together with two other Enderby whalers Brisk and Fancy were sold to the company and, with prospective colonists and fully provisioned, set sail from Plymouth for the Auckland Isles on 17 August 1849. At this time Charles Enderby issued a statement saying: I proceed to the colony with the full support of Her Majesty’s Government, and the assurance from the Admiralty that a vessel of war will visit the islands once a month. The islands and the general body of settlers, will, therefore, be amply protected.

The enthusiastic new settlers comprised 72 souls, not including seamen. They included a medical officer, clerks, storekeepers, bricklayers, carpenters, masons, agriculturists and labourers. Many were married and amongst their number were sixteen women and fourteen children. They took with them partly assembled buildings for a new headquarters, a store and 25 houses.

They arrived at the main harbour of Port Ross on 4 December 1849 and made their settlement, which was named Hardwicke. Here they erected the prefabricated buildings and completed a prefabricated boat, most likely the 12-ton yacht Auckland, used by the Lt. Governor. Crops were planted in the uninviting soil and they set about establishing livestock. This was in preparation for the expected harvest of whale oil and whalebone. They even had a defensive battery of four vintage 12-pounder guns. In 1851 another ship, a 250-ton barque Earl of Hardwicke, built for the Company by Whites of Cowes, arrived at the islands.

Their greatest surprise on arrival was that they were not alone as a few years earlier, in 1842, a party of 40 Maori with 26 Mariori slaves from the Chatham Islands1 had migrated here to establish a settlement, where their main industry was sealing and gathering flax. The Maori had brought pigs and sweet potatoes with them (plus firearms looted from Jean Bart2) and were willing to trade with the new settlers; they lived harmoniously together, and helped farm and crew ships.

The new settlement did not proceed well; crops were difficult to cultivate in a climate that could charitably be described as cool and damp, aggravated by high winds and incessant rain. Sheep and cattle escaped into the wilderness and three horses brought from Sydney were useless owing to the swampy nature of the ground. While fishing for domestic consumption was good, deep-sea fishing was unproductive with the three ships on station suffering from rough weather and a lack of whales. In November 1850 the Governor of New Zealand, General Sir George Grey, visited the islands in HMS Fly and left feeling pessimistic about the future of the settlement. As a result, the London based directors sent out a special commission to check upon progress. They arrived at Port Ross on 19 December 1851, and found the company in dire straits and so poorly managed that within three days they had taken control from Charles Enderby, who was forced to resign.

Work at the settlement ceased and under the supervision of HMS Fantome the colony was evacuated. The prefabricated buildings were dismantled for shipment and on 4 August 1852 a sad party of 123 seamen and 92 settlers sailed from Port Ross making for Dunedin. In less than three years this brought to an end the ill-fated settlement of Hardwicke which had seen five weddings, 16 births and the deaths of two infants (with no clergyman, ceremonies were performed by the Governor). Today all that remains is a cemetery containing six graves, of the two infants and four subsequent castaways from shipwrecks.

The Maori/Mariori were not far behind and in 1856 they departed for the Stewart Islands; others returned to the Chatham Islands. A bitter Charles Enderby came first to Wellington and started legal proceedings against his dismissal, which eventually fizzled out and he returned to England towards the end of 1853 when the Enderby Partnership was wound up. He died at Kensington, London in his 80th year at the residence of his unmarried sister Amelia on 31 August 1876.

So we come to the end of a great company of merchant princes which once helped rule the waves over many seas and contributed much to their wealth by exploration, especially in the remote and unhospitable Antarctic regions. The Enderbys were admired by all who knew them and were praised for their extraordinary endeavours by such diverse eminent men as the American author Herman Melville, who knew a thing or two about whaling, and the British Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott.

Notes

- The Chatham Islands were inhabited for centuries past by a peaceable tribe of Polynesians known as Moriori. In 1835 a large number of aggressive Maori from the Wellington district hijacked the whaler Lord Rodney and after bargaining for provisions the captain took them to the Chatham Islands where they occupied the islands, killing many of the natives and enslaving others.

- A French whaler Jean Bart called at the Chatham Islands in April 1839 which resulted in conflict when her 13 crew were massacred and 28 Maori killed. In an episode reminiscent of the Bounty Mutineers, Jean Bart was then plundered and burnt to the waterline. Fearing bloody reprisals, the two Maori tribes involved bartered pigs with the small New South Wales brig Hannah to take them to the remote Auckland Islands.

References

Ash, Stewart, The Eponymous Enderbys of Greenwich, 2015, online at: www.ballastquay.com/the-eponymous-enderbys.html

Byrnes, Dan, Emptying the Hulks: Duncan Campbell & the First Three Fleets to Australia. The Push from the Bush No 24, April 1987.

Dunbain, Thomas, Whalers, Sealers, and Buccaneers. Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society Vol XI Part 1, Sydney, 1925.

Gordon, C.H., The Vigorous Enderbys – Their Connection with New Zealand. The New Zealand Railways Magazine, Vol 13 Issues 9 & 10, Wellington, December 1938, 7 January 1939.

Malone, R. Edmond (Paymaster HMS Fantome), Three years Cruise in the Australasian Colonies – Chapter VII – Auckland Islands, Publisher Richard Bentley, London, 1854.

Mawer, G. A., South Sea Argonaut – James Colnett and the Enlargement of the Pacific 1772 -1803, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2017.

McNab, Robert, (Editor.) Historical Records of New Zealand Vols 1 & 2, Government Printer, Wellington, 1908.

Savours, Ann, The Life & Antarctic Voyages of John Briscoe. The Journal of the Hakluyt Society, London, July 2021.