- Author

- Kingsley Perry

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The death of Prince Philip on 9 April 2021 at the age of 99 gave rise to considerable interest in his association with Australia. This was described in an article Memories of His Royal Highness Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh in the Naval Historical Review, March 2021 edition.

Prince Philip is said to have visited over twenty times, first in his capacity as a naval officer during the Second World War, and then in his official capacity as Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. His first such visit in the latter capacity was with the Queen on her post-coronation visit in 1954. It was just before their wedding in 1947 that he had been granted the title of Royal Highness and created Duke of Edinburgh (along with some other titles). Apart from his many royal titles, he achieved high naval rank, including Admiral of the Fleet. On his 90th birthday the Queen conferred on him the title of Lord High Admiral.

But was he the first Duke of Edinburgh to visit Australia? And was he the first Duke of Edinburgh to have naval service and reach Admiral of Fleet? No. He was beaten and, in at least one respect, overshadowed by Prince Alfred Ernest, Duke of Edinburgh, the second son and the fourth child of Queen Victoria.

Prince Alfred was born on 6 August 1844 at Windsor Castle. He was second in line to the throne until his older brother Edward became king and had children. In 1856 it was decided that Prince Alfred would join the navy. Having passed the required tests, he was appointed as a midshipman and posted to HMS Euryalus, a fourth-rate wooden-hulled screw frigate.

He remained in the navy and was promoted to lieutenant in 1863, to captain in 1866 and in command of the frigate HMS Galatea (at the age of 22). Galatea was a state of the art 26-gun sixth-rate wooden screw frigate. She was launched in 1859 and saw service in the Channel Squadron, in the Baltic and Mediterranean, and then on the North American and West Indies Station before returning home and coming under Prince Alfred’s command.

Queen Victoria had been concerned about her successors, particularly Prince Edward, her first-born and heir and the brother of, and chief influence on, Prince Alfred. Prince Alfred was clearly a little out of control himself, with interests that were not particularly becoming of a royal. A world tour would give him a responsible mission and at the same time cement Britain and the monarchy in the colonies, including Australia. It was decided that this is what he would do. He would be the first member of the Royal Family to visit Australia.

With a crew of 540, Galatea set off in 1867 for Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town, and then Australia. At the time Australia was a raw colony and a long way from Mother England. However, calls for a break from the monarchy were under constant discussion even then. Breaking completely and installing Prince Alfred as King of Australia was even considered. Cementing the ties to Britain was a paramount purpose of the tour. This was a task that the prince clearly thought he could undertake without unnecessarily interfering with his own agenda of extra-curricular activities. There was great excitement in the colony and preparations were made to keep the prince occupied in attending tours, marches, salutes, balls, banquets, processions, parties, hunting trips, aboriginal corroborees and various sporting events. It became apparent, however, that the 24-year-old prince was quite adept at having a separate good time. It was apparent too that he was attracted to and by the ladies.

The first port of call was Adelaide where there were great celebrations to honour the first Royal Family appearance in the colony. While there was joy and delight directed towards him, he soon attracted a reputation for actively seeking solace in his personal agendas. This continued into his visit to Melbourne and regional centres where he was welcomed with displays of adoration for the Crown, open arms and declarations of loyalty and affection. On the other side, however, extra-curricular night activities were in full flight. These side issues became well-known and led to criticism, but did not diminish to any great extent the excitement and the affection the public held for the prince and the Crown. There still remained, however, some calls for a republic. There was also some perceived threat from the Fenian movement, arising from the troubles between Britain and Ireland.

After Melbourne, Galatea carried the prince and his party to Tasmania, and then to Sydney. There a great crowd welcomed the ship to the harbour and the prince to an unexpectedly eventful visit. Huge events took place, attended by hundreds of thousands of the local population. Declarations of loyalty were apparent. At the same time, the prince exhibited as much interest, if not more, in his own personal (and by now, well-known) agenda. He did manage to fit in a short visit to Queensland, but did not leave a particularly good impression with his hosts there.

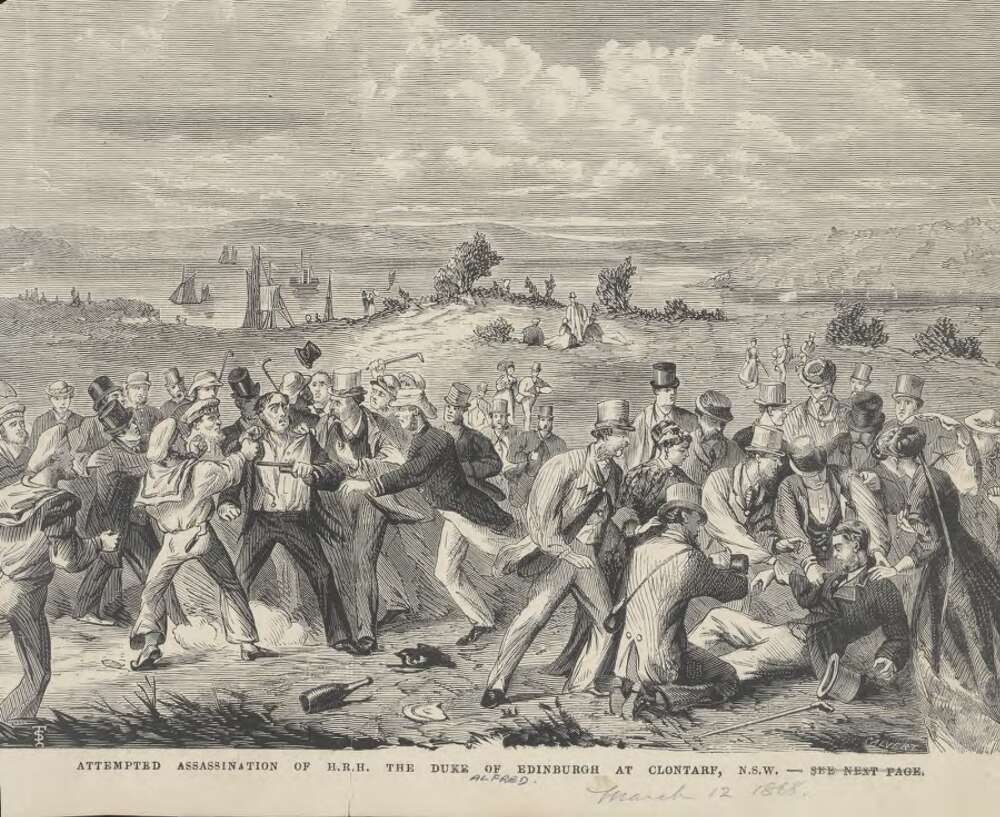

Back in Sydney, on 12 March 1868, a huge picnic at Clontarf, on a northern harbour foreshore, was organised to raise funds for the Sailors’ Home. This was to be one of the final events of his visit, and appropriate lavish arrangements were made. About 1,500 guests were invited and provision was made for many crates of champagne, beer and other drinks, and copious amounts of food. There were to be sports and games, and a corroboree. It was a fine and sunny day, and the harbour swarmed with suitably adorned boats and ferries of all sizes, including the Galatea and accompanying warships.

Thirty-seven-year-old Mr Henry O’Farrell also came along to the picnic. He had migrated from Ireland with his family as an 8-year-old. Irish blood ran strongly in his veins and he embraced the Irish cause and rejected British royalty with similar vigour. He was a ‘failed’ priest and a discontented drifter. Now it was time to make a difference. Armed with two six-chamber pistols, he took up temporary residence around Circular Quay and was able to see the prince, at times at close quarters. He had planned to shoot him at Circular Quay and another location, but those plans were thwarted. He decided he should try his hand at the Clontarf picnic, making his way there by one of the crowded ferries.

At the picnic, now holding a crowd of some 3,000, O’Farrell made his way toward the royal party. The prince had finished lunch and was making his way in company across open ground near the shore, with O’Farrell inconspicuous in pursuit. He made his way to within two paces of the prince, pulled out a pistol and shot him in the back. Chaos reigned. O’Farrell was set upon and beaten, and calls were made for him to be lynched. Amongst other utterances, he called out ‘God love old Ireland, Old Ireland forever’. In the meantime, calls were made that the prince had been killed, but this was not the case. He was indeed badly wounded, but not fatally. Deflected by his braces, the bullet had missed his spine and travelled about 12 inches into his chest, missing vital organs. After some time, he issued a statement that he was fine and this was received with cheers from the milling crowd. He was then taken by ferry to Government House for treatment and recovery. O’Farrell, by now a bloody mess, was taken under heavy guard to Darlinghurst Gaol. And so the tour was suspended, together with any hopes of a republic for the time being.

While the prince was recovering for some six weeks, his transgressions were being overlooked and were overshadowed by the outpouring of affection, compassion and regret. It was decided that he should return home as soon as he was fit to do so. The remainder of his tour, which was to have included New Zealand, Tahiti, Hawaii, Peru, Chile, Uruguay, Brazil and the West Indies, was cancelled. Meanwhile there was the issue of what to do about Henry O’Farrell.

There was no doubt that O’Farrell shot the prince. But why? His utterance about Ireland, coupled with recent instances of shootings in England, led to the suspicion that the Irish Fenian movement was involved. A search was made for accomplices and rewards were offered for information. The Colonial Secretary Henry Parkes was convinced of the involvement of a Fenian ‘terror cell’, hopeful, it would seem, that it would deflect blame from anything associated with a loyal and royal-loving colony like Australia. Despite all the allegations, insinuations and investigations, in the end no accomplices into activities with treasonable purposes were identified.

Meanwhile, fallout from the shooting continued. Respect for the monarchy was enlivened. Some laws were varied to expressly forbid certain ‘seditious’ activities that reflected poorly on or with disrespect to the Queen. The Fenian movement was highlighted as a cause of friction and the loyalty of the Irish in general and the role of the Catholic church was questioned. The prince’s earlier behaviour was forgotten as sympathy smothered that memory. A number of parks, gardens, streets and buildings adopted his name, and there was fundraising for a new Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney and the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne.

One day after the shooting an inquiry began before a magistrate. O’Farrell was charged with wounding with intent to kill. After pleading not guilty he was committed to stand trial on 26 March, a fortnight after the shooting. He was represented at the trial, and it was made clear that there would be no dispute about the shooting, but that at the time he was a person of unsound mind. However, evidence brought to support this line of defence at the trial was limited. Evidence by the prosecution witnesses did not suggest he was acting strangely. It took less than an hour for the jury to find him guilty and he was sentenced to be hanged. The verdict was hardly surprising. The trial had been speedy and the reporting of the shooting and the Irish issues made the selection of an impartial jury virtually impossible. The defence had insufficient time to gather evidence to support the defence of insanity. O’Farrell awaited the pronouncement of the death sentence.

Prince Alfred was due to leave Sydney on 6 April to return to England. He had taken an interest, not surprisingly, in the trial of his shooter, but rather surprisingly took a sympathetic view. On the day before his departure, and after receiving a letter from O’Farrell’s sister, he wrote to the Governor suggesting that the trial had been held in haste and requesting that the sentence be referred to the Queen. In the end, this request was not acceded to. Had it been, he might well have been spared. There was indeed uncalled evidence that O’Farrell was of unsound mind (at least to some degree) and that Colonial Secretary Parkes had acted improperly, involving himself in the investigation, speaking with O’Farrell and promoting the Fenian movement’s involvement. (O’Farrell, in a note to Parkes written the day before his hanging, denied involvement of anyone else, saying that his earlier statements about this were a fabrication). In the end, O’Farrell was duly hanged in Darlinghurst Gaol on 21 April, a little under six weeks after the shooting.

Prince Alfred departed from Sydney on 6 April. He was lauded after his recovery and spent a few days giving gifts and speeches, and receiving gifts and visitors. Thousands flocked to the harbour to witness the departure of Galatea and her commanding officer Captain Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh. Ten weeks later the prince was reunited with his mother Queen Victoria and others in the Royal Family. In England he was met with praise and a warm welcome after his deliverance. He continued his naval career and was eventually promoted to Admiral of the Fleet. In 1893 he succeeded as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha when he moved with his family to Germany. In poor health, he died in July 1900, a week short of his 56th birthday.

The prince’s world tour was perhaps the greatest achievement of his regal career. Since then there have been about fifty royal visits, the greatest of all being, of course, the post-coronation tour in 1954. Prince Philip was a champion in the royal stakes, both in his capacity as a senior member of the Royal Family and as a gentleman and person of grace and honour. Prince Alfred, his predecessor as Duke of Edinburgh, was not in the same category and did not achieve the same reputation, although perhaps he did not have quite the same opportunities. However, the attempted assassination of Prince Alfred at that picnic at Clontarf in 1868 certainly enhanced his reputation at that time in Britain, Australia and the monarchy, more than might otherwise have been the case.

Prime reference:

Harris, Steve, The Prince and the Assassin. Melbourne Books, Melbourne, 2017