- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2019 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Many volumes have been committed to the deadly encounter between the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney and the German raider HSK Kormoran. Depending on which side of the fence you sit, this can be seen as the greatest single tragedy to befall the Royal Australian Navy, or a magnificent victory by the Kriegsmarine. An Australian naval audience could be expected to have considerable knowledge of the Sydney/Kormoran encounter, but know little of the similar and equally intriguing Stier/Stephen Hopkins engagement. The primary role of German auxiliary cruisers in the war at sea was to delay and paralyse Allied shipping by destroying enemy commerce. They were therefore offensive vessels whereas Allied armed merchant cruisers were defensive, with their main role the protection of merchant shipping. An auxiliary cruiser often masqueraded as a peaceful vessel well suited to a particular area, then at the last moment removing her disguise to surprise and overpower an opponent.

During WWII the Kriegsmarine commissioned ten1merchantmen as auxiliary cruisers, colloquially they were also known as commerce raiders. There were two classes: heavy cruisers and light cruisers. Kormoranwas the largest of the heavy cruisers at 8,736 grt, with a length of 164 m and maximum speed of 18 knots, manned by 401 men. She carried an armament of 6 x 150 mm, 2 x 37 mm and 5 x 30 mm guns, plus 6 x 21-inch torpedo tubes and 2 x Arado196 seaplanes.

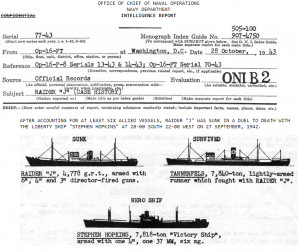

HSK Stier was a light cruiser and the last of her type to escape the blockaded Axis coastlines and gain access to the open seas and lucrative Atlantic shipping lanes. Stier was 4,778 grt, 134 m long with a maximum speed to 14 knots, with a complement of 324 men. Her armament however was similar to the much larger Kormoran and she carried 2 x Arado231 seaplanes. Stier’s major drawback was her low maximum speed and the ineffectiveness of her two small aircraft which had been designed for U-boats and could only manage a few feeble flutters in calm water.

Horst Gerlach joined the navy during WWI but had limited operational service when in early 1941 he was appointed to command the requisitioned merchant ship Schiff 23 undertaking picket duty in the Baltic. New orders were received to convert the ship into an auxiliary cruiser and she was commissioned as HSK Stieron 11 November 1941. She was named after the captain’s wife’s star sign Taurus (in German ‘bull’ is Stier). The crew was young and inexperienced and there was little time for work-up.

On 9 May 1942 Stier left the Dutch port of Rotterdam in convoy with an escort of four large torpedo boats and 16 motor gunboats. The darkened ships crept along the French coast but two hours after midnight they were discovered by patrolling Royal Navy Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs) who called for reinforcements and gave their position to the heavy gun batteries above Dover which covered the gap to the coast of France. The convoy had to contend with heavy fire from the 13.5-inch batteries and MTBs attacking from both sides with machine guns and torpedoes. Two of the escorts were sunk with considerable loss of life and one MTB was also sunk, but Stier escaped and made the fortified French port of Royan at the mouth of the River Gironde to the north of Bordeaux. She sailed from here into the Atlantic on 19 May, the last commerce raider to make this perilous voyage.

Because of her relatively slow speed Stierneeded to clear areas where convoys and escorts might be encountered so she entered the South Atlantic where single Allied ships might still be found. The poor performance of her scouting seaplanes also limited her operational range and to improve the chances of success, for a time she joined with another commerce raider HSK Michel. However, sightings were limited but after four months she could claim credit for having sunk three Allied ships including a large American tanker, Stanvac Calcutta.

Stier was now prowling the infrequently travelled waters between Cape Town and South America and had rendezvoused with the supply ship Tannenfels for provisions and to offload prisoners. On Sunday 27 September 1942, in calm seas covered by early morning fog, the two ships had stopped and were drifting with the opportunity taken to employ most of the ship’s company of Stierin cleaning marine growth from her waterline.

SS Stephen Hopkinswas a first generation Liberty ship with an all welded hull, built by Kaiser’s Richmond, California yard, and like many of her sisters was constructed on mass production lines at incredible speed. These relatively bulky general purpose freighters, of a simple British design with reciprocating engines from a past era, could be manufactured quickly and cheaply by largely unskilled labour. With German submarines sinking Allied merchant ships at an alarming rate it was necessary to supply new hulls fast or Britain would be starved of provisions. It is perhaps coincidental that 2,710 Liberty ships were eventually built by United States shipyards, almost exactly the same number (2,780) of Allied and neutral merchant ships sunk by U-boats.

Stephen Hopkins of 8,000 grt was 135 m long and her low powered reciprocating steam engines gave a top speed of 11.5 knots. She had an armament of one 4-inch (102 mm) gun of WWI vintage at the stern, two 37 mm guns forward and two 30 caliber machine guns on either side of the bridge. Under command of her master Paul Buck she had a crew of 41 men and a surprisingly large number of 15 Naval Armed Guards3commanded by Lieutenant Junior Grade Kenneth Willett, USNR. Her youngest crew member was 18-year-old Engineering Cadet Edwin O’Hara who enjoyed volunteering to help with gun drills.

Her maiden voyage had taken her from San Francisco on the US West Coast with wartime supplies and troops for the US supply base at Bora Bora in French Polynesia, then Wellington, New Zealand and Melbourne, Australia. She next proceededtoPortLincolnwheresheloaded grain for Durban, South Africa. Here she took on sugar for Cape Town and was now sailing in ballast to Dutch Guiana (now Suriname) in northeastern South America to load bauxite for New Orleans. After this her crew could expect some well-deserved leave.

The Battle

At 0852 on Sunday 27 September 1942 the fog lifted and the two German ships and the American sighted one another at about 4,000 metres. The Stephen Hopkins had been ordered to stop but thoughts of surrender were far from her Captain’s mind. Stier and Stephen Hopkins simultaneously cleared for action, the former was handicapped in recovering her crew, and wishing to escape, the latter put her stern towards the enemy, presenting a smaller target and bringing her main armament to bear upon the enemy. The first shots were from Stier’s secondary armament which raked Hopkins’s upper deck and critically wounded the First Mate, Richard Moczkowski. With the third salvo from Stier’s main armament she found the range and started to cause havoc. But Stier also received several well directed hits from Stephen Hopkins, one to her steering gear and another in her engine room.

The forward gun crews in Stephen Hopkins also paid attention to Tannenfels, keeping her out of the action and causing slight damage. The main thrust of the action was from the 4-inch gun under the command of Cadet O’Hara which managed to get away 35 rounds with an amazing success rate of 15 hitting their target. Later this brought praise from the unfortunate Kaptain zur See Gerlach who thought he was dealing with another armed merchant cruiser. Towards the end of the action with the remainder of his gun’s crew lying dead or wounded Cadet O’Hara fired the last shots alone. A fewmoments later he was killed by a shell which exploded nearby.

The action continued for about an hour until Stephen Hopkins slid below the waves, by which time all but 19 of her crew and naval gunners were dead. Lieutenant Willett, while severely wounded, remained on the bridge with the captain coordinating the overall return of fire. Kenneth Willet was last seen trying to cut away life rafts just before the ship sank.

Those who fell during the action included Captain Buck, First Mate Moczkowski, Lieutenant Willett and Cadet O’Hara. The survivors managed to get away in the one remaining serviceable boat. Knowing that the prevailing current would take them towards South America, with great perseverance they proceeded on an 1,800 nautical mile ordeal on a diet of mostly malted milk tablets. After 31 days the survivors, now down to 15 men, waded ashore near Barro de Itabapoana north of the then Brazilian capital of Rio de Janeiro on 28 October 1942, to be eventually given a heroes’ welcome in New York before reuniting with their families.

The damage to Stierwas severe with fire taking hold and, with the loss of all power, firefighting equipment was useless. Accordingly, the decision was made to scuttle the ship and transfer all survivors (two men had died in the battle) to Tannenfels.On 02 November 1942 they arrived at Le Verdon-sur-Mer, which is on the opposite side of the River Gironde from where they had set out less than six months before. Their reception was less than enthusiastic with a noticeable lack of medals.

Conclusion

There are many similarities between the Sydney/Kormoran encounter and those of Stier/StephenHopkins. In both cases surprise and a lack of preparedness caused the loss of the superior naval ship. Stieris the only German surface warship destroyed by an American ship in WWII, and the only cruiser ever sunk in combat by a merchantman.

The Australian arrival of this rather ugly duckling seems to have been unheralded, but she was possibly the first of the famous Liberty ships that helped changed the course of the war to sail into Australian waters. In American naval annals Stephen Hopkins is remembered with her master Captain Paul Buck, First Officer Richard Moczkowski and Cadet Edwin O’Hara posthumously awarded Distinguished Service Medals. Lieutenant Kenneth Willett was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross. A destroyer and a building at the King’s Point Merchant Marine Academy (KPMMA) were later named in honour of Captain Paul Buck. A destroyer escort was named in honour of Lieutenant Kenneth Willett and a gymnasium at the KPMMA in honour of Cadet Edwin O’Hara.

Notes:

1.The lastauxiliary cruiser HSK Hansawas the captured British merchantman Glengarrywhich had been converted for commerce raiding but did not see active service in this role.

- SS Stephen Hopkinswas named after a prominent early colonist who became governor of Rhode Island, and was a signatory to the Declaration of Independence.

3.American Naval Armed Guards (NAG) were equivalent to the British Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships (DEMS) concept. While NAG personnel were a part of the USN most had no prior naval background and after a short one-month training course were allocated as gun crews in merchant ships. A DEMS party was usually commanded by a RN Petty Officer or Royal Marine Sergeant.