- Author

- Jarrett, Hugh

- Subjects

- 19th century wars, Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2002 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The French were sighted 150 miles south-west of the Ushant. Kempenfelt crossed astern of the French line and kept up to windward. Using his new signal-book, he turned his ships together into line abreast and adjusted his speed to remain astern of the French but out of gun range. The weather was very squally, so he was content to wait for the French Admiral to make an error. After several hours the French rear began to straggle and the supply ships dropped off to leeward of their escorting naval ships. Kempenfelt signalled his squadron to turn into line-ahead and then follow him through the French battle-line to the supply ships beyond.

It worked wonderfully, and he took supply ship after supply ship and sank four frigates, while nineteen French sail-of-the-line looked on helplessly. Kempenfelt took fifteen supply ships. The French tried to engage, but in a running fight Kempenfelt held them off from his prizes and escorted them into Plymouth in triumph. Kempenfelt and his signalling system had beaten the great tactician de Guichen.

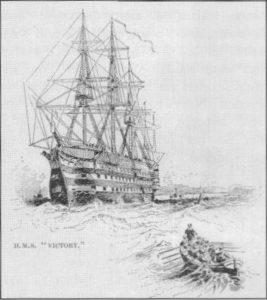

On 11th March Kempenfelt shifted his flag to Royal George which formed part of the fleet under Lord Howe who hoisted his flag in Victory. In August 1782 the fleet was ordered to refit with all speed at Portsmouth and proceed to the relief of Gibraltar. The shifting of weights to heel the Royal George, to facilitate the repair of a leak, probably caused a large part of her bottom to fall out and she sank, taking with her eight hundred persons including Rear Admiral Kempenfelt. Victory’s boats rescued a few survivors.

The Relief of Gibraltar

On 11th, October, Howe with thirty four sail-of-the-line found forty eight enemy ships anchored off Algeciras. He covered the store-ships he was escorting and saw them safely into Gibraltar, thus completing the relief on 18th October, allowing him to challenge the enemy on the following day off Cape Spartel, west of Tangier.

The enemy had the advantage of numbers and a favourable wind, but they held off until after dark and approached with some hesitation. The battle was joined in moonlight and continued for four hours when the enemy broke off the action. Howe had given orders for Victory’s gunners not to fire until they could see the buttons on the enemy’s coats. So Victory did not open fire although she was as close as any other British ship.

Revolutionary France declares war

When the peace of 1783 came, Victory with other ships went back into Reserve in Ordinary, but as war with Spain seemed probable in 1790, Victory was recommissioned as the flagship of Admiral Hood, but the situation abated to be replaced by a Russian scare in 1791 which also faded. In 1793 Revolutionary France declared war on Britain and Holland and Victory, as Lord Hood’s flagship in the Mediterranean fleet, cruised off Toulon until the city declared in favour of the Royalists. Hood then took the fleet into Toulon and held the city for four months – a forlorn endeavour against overwhelming odds. The fleet took as many Loyalists as it could to the island of Elba, but many were left behind to be massacred by the revolutionary zealots.

Victory was at the sieges of Bastia and Calvi and landed sailors to man the naval guns sent ashore. By August 1794 Corsica was under British control, but Admiral Hood’s health broke down and he returned to England in Victory. Rejoining the Mediterranean fleet, Victory became the flagship of Rear Admiral Man on 8th July 1797.

The Battle of Cape Vincent

On 3rd December 1795, Admiral Sir John Jervis made Victory his flagship and started his close blockade of Toulon with his fleet rarely entering port. The fleet was provisioned at sea and remained on station in spite of any requirement for repairs or re-rigging. The Royal Navy held the sea and the French were bottled up in Toulon. But French successes were mounting up elsewhere and Spain had joined them, so Britain found herself without bases in the Mediterranean, Therefore, in the autumn of 1796, Admiral Jervis reluctantly followed orders from the Admiralty and withdrew his fleet to Lisbon.