- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Parramatta I

- Publication

- December 2020 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

In this our 50th year it is well to reflect on some of the more important projects undertaken by the Society and none is perhaps more worthy than conceiving a memorial to the first of His Majesty’s Australian Ships – the torpedo boat destroyer HMAS Parramatta.

One of our members, Bruce Bird, recently sent us a transcript of an address given by our founding father, Lew Lind, to the ACT Chapter of the Naval Historical Society on 24 June 1974 which tells the story of this project.

As Lew’s entertaining paper covers 13 pages of typescript, in the interest of brevity we have taken the liberty of some minor editing. There is a decided twist to this story, unknown at the time of Lew’s address.

Lew Lind’s Address

Three major projects have been undertaken by the Society but the most interesting from my point of view was the salvage of HMAS Parramatta, the first ship built for the Commonwealth Naval Forces1 (CNF). Parramatta was more than a 700-ton torpedo boat destroyer; long, narrow waisted, and far from being a beauty, she was the first symbol of Australian nationhood. Not only was she the first ship built for the Commonwealth, she was also the cheapest, costing just £82,500. As a further point of interest, she was one of the last class of destroyers built with an outboard rudder.

Parramatta was built by Fairfields at Govan in Scotland. Her plates were of Swedish steel fully galvanised before being riveted in place. I can vouch for the toughness of the steel as even today it will tear the teeth from a hacksaw.

She was launched by Mrs Asquith, wife of the British Prime Minister, on 9 February 1910 and christened by the first bottle of Australian champagne ever exported. The words spoken by Mrs Asquith on that occasion are still stirring. ‘First born of the Commonwealth Navy – I name you PARRAMATTA. God bless you and those that sail in you.’

She was fast. Although her engines were capable of developing only 10,000 hp, her best speed on trials was 29.6 knots. Later in her career she was to clock greater than 30 knots. HMS Parramatta was commissioned by Captain Frederick Tickell CNF on 10 September 1910 and sailed from Portsmouth in company with her sister HMS Yarra on 19 September – said to be the first King’s ships to leave that port without rum tubs.

The two ships received tumultuous welcomes at all Australian ports. The Melbourne Age dubbed them the Lion’s Cubs, a name the RAN was to retain throughout World War One. Arrival at Melbourne on 10 December 1910 was marred by the death of a respected local officer, Engineering Lieutenant William Robertson, who just hours from returning home to his family was lost overboard from Yarra off Port Phillip’s notorious ‘Rip’. While his body was recovered, he could not be revived.

The destroyer’s war career was varied. If luck had been with her she would have won glory in New Guinea. At the rendezvous of the fleet at Rossel Island on 7 August, the destroyers Parramatta, Yarra and HMAS Warrego were told the German Fleet was at Rabaul and they were to carry out a night attack. The German Fleet was not to be found and the attack was an anti-climax. A month later Parramatta and her sister ships repeated the operation when Rabaul was occupied. One of the prisoners taken on that occasion was an Australian blue cattle dog which the crew named ‘KB’ after a well-known beverage.

There followed an intensive period of patrolling during which the fleet sought to find German shipping which was known to have escaped from New Guinea. Parramatta captured two vessels, including Meklong which was requisitioned into naval use. While engaged in these operations Parramatta was present when the submarine AE1 was tragically lost. With her sister Warrego she sailed 260 miles up the Sepik River, a record which has never been equalled by a vessel of similar size.

In 1916-17 Parramatta operated in the China and Philippine Seas on contraband patrols. During the twelve months spent in these waters she boarded 40 ships. The Australian Torpedo Boat Flotilla was transferred to the Mediterranean in the second half of 1917. On her fourth day in this sea, 16 October, Parramatta bagged the RAN’s first U-boat.

As the U-boat was sighted the captain rang on full speed and prepared to ram. Just as the destroyer reached the submarine’s estimated position the submarine half surfaced and Parramatta’s bow struck it amidships and ran over it. A depth charge was then dropped which exploded in the destroyer’s wake. A dent in Parramatta’s stern from this incident can still be seen today.

In November 1917 the destroyer was instrumental in saving the Italian troopship Orione which had been torpedoed by a U-boat off Brindisi. Parramatta took the damaged vessel in tow and was barely under way when a U-boat broke surface off her bows. With a 10,000-ton liner in tow little headway was made and the submarine escaped.

Parramatta’s commanding officer and senior officer of the RAN destroyer flotilla, Commander William Warren RAN, died in Brindisi on 13 April 1918 after failing to recover from a fever which was particularly virulent at that time. Two days after his death a letter was received announcing the award of a DSO to Commander Warren for his action in the sinking of a U-boat.

Parramatta was present at the Turkish surrender in October 1918. She anchored off the Sultan’s Palace at Constantinople for the ceremony. The ship had the honour of accepting the surrender of the German Admiral and his staff. With her sister ships of the Australian Flotilla she was employed in operations against the Bolsheviks in the Black Sea. Parramatta was the despatch ship plying between Sebastopol and Constantinople. The destroyers returned to England for an extensive refit at the end of 1918.

The ship’s career after return to Australia was unimpressive. Most of the period 1919 to 1928 was spent either in reserve or as a training ship for reserves. In 1928 Torrens and Huon were sunk as target ships off the coast. Warrego, which was earmarked for a similar fate, sank beside the wharf at Cockatoo Island. Before Parramatta and Swan could be disposed of, the NSW Government proposed the two ships be converted as accommodation hulks for convicts from Long Bay Goal employed in road-making in Ku-ring-gai Chase.

The vessels were towed up the Hawkesbury River to Cowan Creek but before the plan could be implemented the Liberal Government was defeated. The incoming Labour Premier, Jack Lang, thundered that convict ships had been dispensed with 80 years before, and he would not tolerate their revival.

The two ships were offered for auction and were sold to a boatshed operator, Mr Rhodes of Jerusalem Bay, at £24 for the two. It was his intention to convert the ships into fishermen’s huts but the Ku-ring-gai Chase Trust would not approve the plan. Over the next five years the ships changed hands a number of times and were employed for a time as gravel barges. However, in 1935 it was decided to return the vessels to Cockatoo Island for breaking up.

The two ships were taken in tow by a single tug but as they neared the Hawkesbury Railway Bridge a southerly buster struck and broke the tow. Swan was swept upstream and foundered in 16 fathoms of water at the entrance to Jerusalem Bay. Parramatta grounded on the northern end of Milson Island. A subsequent storm drove the hulk to her final resting place at the base of a cliff opposite Milson Island on the north bank of the river.

In 1936 Crockett Bros., the last owners of Parramatta, converted her into a reservoir where water was fed into her hull from a nearby waterfall and pumped to homes along the river front. During the immediate post war years her midships was cut away for scrap.

Three attempts were made to preserve the vessel. In 1932 former crewmen tried to raise funds to convert her into a museum but the scheme failed. In 1952 the Naval Association proposed a similar plan, which also failed.

In 1970 this Society suggested to the Naval Board that an attempt should be made to salvage a section of Gayundah or Parramatta. The Board agreed to carry out a feasibility investigation on the latter. The study reported that the bow and stern sections could be salvaged. It stressed that the operation would be difficult and cost would be over $10,000. Several weeks later the Board informed the Society it was not able to do anything about the salvage.

In April 1973 the Society proposed to Parramatta City Council that the bow and stern sections of the ship be salvaged and erected in Parramatta as a memorial to all ships of the name. I addressed a public meeting and later a meeting of the City Council on the project which resulted in the Council agreeing to underwrite the cost of the project subject to a public appeal being conducted for $10,000.

Tenders were called for salvage, and one received for $5,900 from Sydney Bridge and Wharf for the cutting and transport of the sections to Parramatta. A team from the Society marked the sections to be cut and in July work commenced. On 13 July the bow section was lifted onto a barge and two days later the stern section was removed.

It is interesting to note there were technical problems associated with the salvage. Firstly, the depth of water alongside the hulk at high water was two feet. The draft of the floating crane was four feet. This was overcome, much to the horror of the engineers, by warping the floating crane alongside and working it down by twisting into the mud. Another problem was burning the steel. Galvanising of the 1910 period gives off a highly toxic gas. The problems were overcome, mainly by faith and enthusiasm. The barges and the floating crane were warped out into deep water after salvage.

I should add that maximum publicity was given to the operation. Television coverage was arranged, we carried out live radio broadcasts from our control ship, South Pacific, and we supplied the press with photographs and copy. South Pacificwas a 60-foot luxury cruiser offered by a businessman, with two stewards on board to supply continuous refreshments.

I should tell you that we found no bodies in ship’s bilges but we did find Parramatta’s ghost. Sealed in the compartment nearest the stern was a large spanner which must have haunted generations of engineers as it banged and rattled hollowly through the ship. The barges were towed 20 miles downriver to Bayview to be rigged with navigation lights for the passage around to Sydney. Here we obtained another splurge of unexpected publicity as the barge carrying the bow section was holed and promptly sank. It took three weeks to raise the barge and its precious cargo and carry out repairs.

On 12 August our Treasurer (Peter Churchill) and myself boarded the barge carrying the bows off Sydney Heads. We erected a jack staff and hoisted a huge Red Duster – the first flag that the ship flew. Calico signs were draped over the sides ‘HMAS PARRAMATTA – FIRST SHIP OF THE RAN GOING HOME’. As the barges came past Garden Island a fanfare of bugles from HMAS Sydney saluted her venerable grandparent. All Sydney television stations and newspapers gave the event great coverage.

The sections of the old destroyer were unloaded at the navy wharf at Rydalmere only after the Society had given an indemnity for $10,000 against damage to Commonwealth property. To transport the two sections of the ship to their final destination, a distance of four miles, we needed a 48-wheel low loader and prime mover and two mobile cranes.

The stern section was transported to a Council holding yard at Granville without a lot of trouble. The bow section was a different kettle of fish. It was 25 feet high but regulations only permit a limit of 16 feet in height to be moved on public roads. Exceptions required three police escorts – two motor cycles and a car and two electricity authority vehicles to lift power lines along the route. The load could only be moved between dawn plus two hours.

Although the route had been surveyed, we soon came to an immoveable snag. After leaving the navy depot in the cold dawn we crawled up to Victoria Road, which is a main artery to the city. Arriving at the peak of the morning traffic vehicles had to be run up onto footpaths and to make its turn, the low loader had to mount the median strip. We proceeded two miles along Victoria Road with the traffic in absolute chaos. Eventually, we arrived at Rydalmere pedestrian bridge and to our horror the load was two feet three inches too high to pass underneath. Those responsible had forgotten to allow for the height of the low loader. In similar chaotic conditions we retraced the journey to the naval depot.

Over the next two days we carried out surveys to find an alternative route. There was only one and this meant dropping the electric train wires on the main northern lines and disrupting rail traffic. Returning from this sortie we paused again at the pedestrian bridge where a small road was noticed leading into the Psychiatric Hospital. Following it through, we found it took a right-hand turn that bypassed the bridge. We measured the turn and found the load could pass with three inches to spare. An indemnity of $50,000 was required by the Hospital Commission, but permission was granted.

Next morning, we repeated the process of disrupting the traffic and mounting the median strip into the Psychiatric Hospital. We were fortunate the Parramatta Council had taken out a large insurance policy as the heavy-duty wheels of the low loader chewed up both the lawn and garden and on one sharp turn at the back of the hospital the corner of a building was damaged. The inmates of the hospital had been evacuated beforehand and they appeared to derive considerable pleasure from the operation. We eventually arrived at the council yard at 9.20 am, our path marked by the broken limbs of trees and shrubs which lined the streets.

What Happened Next

Financial problems dogged the project for the next three years but in 1976 the Council discovered a grant which might cover the setting up of the memorial. A site had been selected combined with a planned hovercraft terminal. By 1980 as the hovercraft terminal lapsed the plans for the memorial were modified to only include the stern section of the ship.

After all this careful planning and execution, which had taken three years, the project came to a halt. The Council were possibly in a quandary about the incorporation of the memorial into a ferry wharf and this did not proceed. Eventually the project once again gained traction and the Parramatta Council found a suitable memorial site near Queen’s Wharf steps on the banks of the Parramatta River, this was the site of a landing place used by early colonial governors on the way to their official residence in nearby Parramatta Park. The Council in its wisdom decided that the stern section only was suitable for its memorial and no more attempts would be made to relocate the bow. And so it was that at 11.00 am on Saturday 13 June 1981 Admiral Sir Victor Smith AC KBE CB DSC unveiled the memorial.

Lew was not a man to be deterred by such misadventures, because he had put so much effort into formulating this project. If Parramatta City did not want the bow – where to next? The unwanted bow had been returned to the Naval Yard at Rydalmere.

In 1984 Lew suggested to the General Manager of Garden Island Dockyard that it would be fitting for the bow of the RAN’s first ship to be mounted on the eastern point of Garden Island. The proposal was referred to Navy Office and later that year the sum of $5,000 was allocated for the project.

The bow was finally erected at Garden Island in early 1986. The question arose who should officially open the second memorial and Lew suggested HRH Price Phillip who was to be the reviewing officer at the 75th Anniversary Celebrations later that year. The proposal was passed to Navy Office but declined on the grounds of the short notice and that the Prince’s programme would be over-extended. Our disappointment at this decision was passed on to a friend in England which resulted in a last-minute change in the official programme which now included unveiling of the Parramatta memorial.

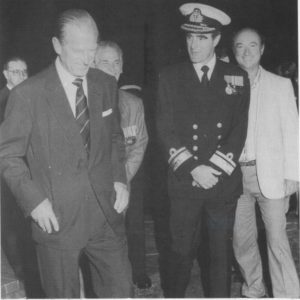

The unveiling ceremony was held at 6.30 pm on Friday 3 October 1986 and was attended by several hundred members of the Society, and members of the ship’s company of the present HMAS Parramatta provided an honour guard. His Royal Highness was met by Rear Admiral Nigel Berlyn and Mr Lew Lind, and all members of the Committee were presented.

And so the Society’s first, largest and most enduring project was accomplished. The public image of the Royal Australian Navy had been promoted and preserved for the present and future generations in not one but two memorials to our first fighting ship. It was also fitting that His Royal Highness unveiled this memorial as he became an honorary member of our Society in 1970, and we therefore have an Admiral of the Fleet amongst our august members.

In his welcoming address Rear Admiral Nigel Berlyn said: ‘In 1970 the Naval Historical Society of Australia proposed a salvage operation and in 1973 the Society, in conjunction with the Parramatta City Council, removed the bows and stern of the ship from what was left of the hulk. Subsequently the stern was embodied in a memorial at Parramatta on the banks of the River after which she was named. Tonight the bows are at last positioned on the northern tip of Garden Island pointing seawards where they can be seen by present and future ships of the RAN as they pass upon their duty.

Fifty years past we started on a journey to preserve a memorial to the first HMAS Parramatta, and we ended up with not one but two memorials, but it took sixteen long years to complete this project2. It started with the vision and determination of one man and as he has said ‘what seems impossible can be achieved with patience and enthusiasm’. That man of course was the long-standing President of the Naval Historical Society of Australia – Lew Lind.’

The Garden Island Dockyard Museum

On the day following the Fleet Review the Garden Island Dockyard Museum, a forerunner of the Naval Heritage Centre, was officially opened in an annex to the historic Marine Barracks Building. The opening ceremony performed on Sunday 5 October 1986 by Admiral Sir Victor Smith formed part of the RAN’s 75th Anniversary Celebrations. An estimated 250 members and guests attended the ceremony and later, 550 visitors passed through the museum.

Notes:

1 Parramatta launched on 9 February 1910 and her sister Yarra launched on 9 April 1910 as ships of the Commonwealth Naval Forces (CNF). They were commissioned into the Royal Navy for their outward voyage and on reaching Australia reverted to the CNF until becoming His Majesty’s Australian Ships after the formation of the RAN on 10 July 1911.

2 There is another memorial to His Majesty’s Australian Destroyer Flotilla 1914-1918 with a stained-glass window dedicated to them in the Naval Chapel at Garden Island Dockyard, provided by members of the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron and the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club and unveiled by the Governor General Sir Isaac Isaacs on Sunday 27 November 1932.