- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- History - general, Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

This article originally appeared in the Magazine of the Institute of Conservation (ICON News) Issue 101, August 2022 and is reproduced, with minor amendments, by kind permission of the author and the editor of that magazine.

Dr Toby Jones, Curator of the Newport Medieval Ship Project, tells the story of twenty years’ work on an important archaeological find.

In ancient times the estuary of the River Severn was a gateway by which goods were imported into and exported from Britain to Gaul (France) and Iberia (Spain and Portugal). Feeding the mighty Severn were a number of tributaries including the River Usk leading to the important Roman settlement and fortress of the 2nd Augustan Legion at Caerleon, and later a deep water new port further downriver (Newport).

What does this have to do with Australia? As Dr Jones explains, there is a relationship via one of the most important shipwrecks discovered and preserved for many hundreds of years in the muddy banks of the River Usk. This ship was built in the Basque region of northern Spain. As most of our readers know there is now a considerable link between the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and the north-western Spanish region of Ferrol. Most of the present-day larger ships in the RAN fleet originated here at the state owned Navantia shipyards. These include: two helicopter landing dock (LHDs) Adelaide and Canberra freighted by heavy lift ships to Australia for fitout; three guided missile destroyers (DDGHs) Brisbane, Hobart and Sydney designed by Navantia but mostly built in Australia; and two auxiliary oiler replenishment (AORs) Stalwart and Supply, built by Navantia.

Ferrol has a long-standing pedigree in shipbuilding even before the Spanish Royal Academy of Naval Engineers was established there in 1772, a few years prior to the arrival of the First Fleet in Terra Australis.

Discovery, Excavation and Recovery

Twenty years ago, in the summer of 2002, a remarkable archaeological find was unearthed during redevelopment work in Newport. During the building of a Riverfront Theatre and Arts Centre the remains of the wooden hull of a late medieval merchant vessel were found preserved deep in the alluvial clay along the River Usk. What followed was an intensive five-month excavation, an in-situ documentation programme, and a recovery effort that required the complete disassembly of the waterlogged ship into thousands of individual components. This discovery proved to be the remains of a three-masted armed merchantman, with a length of 116 feet and a beam of 27 feet (35 m x 8.2 m); of about 160 tons burden; she was indeed a great vessel of her time.

In addition to her timbers, around a thousand artefacts and environmental samples were also recovered. She was clinker built of overlapping oak planks fitted to oak frames and waterproofed with animal hair and tar. Dendrochronological (tree ring) analysis suggested that the ship dated to the mid-15th century, with strong evidence of Iberian connections in the form of Portuguese coins and ceramics. Later research firmly dates most of the hull planking to about 1449, with precise origins of the oak timbers identified as coming from an extant forest near San Sebastian in the Basque region of northern Spain. The find sparked intense local interest and was deemed of international significance; it was quickly proposed that the vessel be fully excavated and conserved so that it could be later reassembled and displayed.

Several factors served to complicate the excavation, recovery and disassembly, including the sheet pile coffer dam surrounding the vessel, the numerous concrete piles inadvertently driven through the hull, and the interlocking/overlapping construction and fastening of the vessel. The depth of the excavation also necessitated the use of cranes to lift the timbers out of the pit and onto flatbed lorries.

All of the recovered archaeological material was kept wet in a series of temporary tanks before eventually ending up in some seventeen 25,000 litre PVC tanks (with external scaffold pipe framework) inside an industrial unit in the city. The water was changed on a regular basis but little or no salinity was detected. The individual hull timbers, varying in size from finger-sized fragments to the 20 m long keel, were all labelled with animal IDs (cow ear tags). Longer timbers were cut into more manageable lengths, both for ease of initial handling/documentation and for later fitting into a freeze-drier.

The ship appears to have been intentionally positioned on a pre-erected cradle in a side channel/pill and was undergoing refit or repair, some time after the spring of 1468 but before the winter of 1469. It appears that the ship heeled over and flooded, with contemporary efforts to raise/refloat the vessel ultimately unsuccessful. Substantial portions of the upperworks of the ship were subsequently removed, along with the salvaging of all the readily reusable items, including the anchors, masts, guns and larger rigging elements.

Post-Excavation Cleaning and Documentation of the Hull Timbers

In 2004, archaeologists and conservators began a multi-year effort to clean, record, analyse and conserve the timbers and artefacts. The hull timbers, predominantly oak, were well-preserved, both by the extensive use of wood tar during and after initial construction, and by the ideal depositional environment for organics – wet, cold, dark, and anoxic river clay. The hull timbers were largely covered in concretions caused by the corrosion of the numerous wrought-iron clench nails used to hold the hull planking together. These concretions (along with tar, animal fibre caulking and barnacles) were removed using dental tools, small chisels, toothbrushes and lots of water. The preservation of details on the surface of the timbers was remarkable, with thousands of examples of inscribed lines (design marks), toolmarks and fastener head impressions. During the cleaning process, tar, iron and animal fibre samples were taken for future analysis. The 3D digital documentation methods detailed below were complemented by hand written timber record sheets and selective digital photography.

Like many archaeology rescue projects, archaeologists working on the Newport Ship excavation were under pressure to complete their investigations quickly. While they were able to document the position and context of artefacts and ship timbers with traditional hand drawings, photogrammetry, photography and videography, they were unable to record each timber in the detail necessary to create a reconstruction model of the ship (the reconstruction of the original shape of the hull form of an archaeological ship find is seen as a key research goal within nautical archaeology).

After cleaning, the hull timbers were recorded using 3D digital documentation technology, including contact digitisers (FaroArms) and digital photography. A laser scanner was used to record important tool marks and artefacts. Different layers/colours in the Rhinoceros3D CAD modelling software were used to organise the data and build up a detailed record of the geometry and fastener type and position for each timber. The 3D wireframe drawings produced by the contact digitisers were used as a basis for the creation of digital solid models, which were in turn 3D printed using selective laser sintering technology. These individual 1:10 scale model ship timbers were assembled into a 3D model of the surviving original hull. This physical scale model then served as a foundation on which to ghost-in the missing areas of the hull. This model was digitised and used to create accurate reconstructions of the original hull form, complete with sails, rigging and cargo.

Artefacts

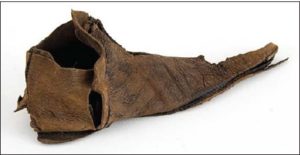

In addition to cleaning and recording the huge assemblage of hull timbers, the team worked on the numerous small finds and samples. Hundreds of artefacts were found during the ship excavation. They ranged from items used in daily life, like earthenware pottery and wooden combs, to defensive items like stone shot and a leather archer’s bracer, complete with stamped Latin inscription. Some finds, like the rigging elements and wooden bowls, were well preserved in the waterlogged environment. Others, like Portuguese coins, cork oak and various foodstuffs, could provide clues about the crew or cargo. Dozens of cask staves and heads were found during the excavation, which indicate that the ship carried wet and dry goods in casks, along with a range of bulk cargoes. Of significant technical importance are the numerous composite artefacts (wood, leather, metal) related to the various pumps found on board the ship.

One particularly interesting find was a silver French coin found purposely inserted into the fabric of the ship. The coin, a petit blanc, was placed in a rebate cut on the inboard face of the keel where it was scarfed over by the stem. The coin features a cross on one side and a crest of the Dauphin of France on the other, and was minted in Cremieu, France between May and July 1447.

The abovementioned objects were documented via digital photography, laser scanner or archaeological illustration. The objects offer potential insight into life on board the ship during mid-15th century. All of the small finds have been conserved, with some already on display at the Newport Museum and Art Gallery, and in the ship conservation centre.

Conservation

Following documentation and dendrological analysis, the active conservation process began on the hull timbers. A concerted effort was made to mechanically remove all visible iron and iron-corrosion products prior to documentation; however, iron staining was still visible. In order to remove further soluble iron salts, a decision was made to use a chelating agent. The first step in the planned polyethylene glycol/vacuum freeze-drying process was pre-treatment with 2% w/v Di-ammonium Citrate to remove the bulk of the soluble iron salts still present in the timbers. A tank full of timber would typically be treated for 4-8 weeks and then rinsed several times with fresh water before new Di-ammonium Citrate was added. In one tank, the first treatment caused 181 mg/litre of iron to come into solution, while the fourth and final treatment of that particular tank yielded only 5 mg/litre of iron in solution.

Following rinsing, a two-stage PEG pre-treatment was commenced, with concentrations of 15% v/v PEG 200 and 5% w/v PEG 3350 used for the planks, and 15% v/v PEG 200 and 20% w/v PEG 3350 used for the frames and other thicker material. PEG was added incrementally until the desired percentages were reached. The tanks were not heated or insulated, but the PEG solution was circulated with pumps. Vacuum freeze-drying followed, with batches of timbers taking 4-6 months per run. Initial estimates of shorter run lengths proved optimistic, as the largely intact (i.e. minimal degradation but waterlogged) timber structure impeded the PEG absorption and subsequent migration of water vapour to the surface. Freeze drying took place both onsite at the ship centre in Newport and later at York Archaeological Trust and the Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth. The final batch of timbers is expected to be freeze-dried by August 2022, marking the end of active conservation treatment, 20 years after initial discovery.

Long-term Storage

The dried timbers and artefacts are currently being stored in two bespoke insulated chambers built inside the ship centre industrial unit. These ‘rooms within rooms’ are made from pallet racking, scaffolding tubes and fittings and 100 mm thick polyisocyanurate boards (PIR – Kingspan/Celotex). Joint seams are filled with silicone and covered with aluminium foil tape. Large double-glazed units set into a removeable door allow public viewing and forklift truck access. Lighting isprovided by four 50-watt LED floodlights. Temperature and relative humidity conditions are maintained using a domestic dehumidifier, with stable conditions being maintained with little energy input. The centre area of each store is filled with rolling racks (again made from scaffold tubing, fittings and OSB board covered with LDPE foam), which allow material to be easily moved around to access the pallet racking.

Reassembly and Display

The ultimate goal of the entire project is the reassembly and display of the medieval ship in a suitable environment. Reassembly trials have shown that the material will generally fit back together well, with the empirical results being bolstered by a re-recording programme which is providing comparative data for the statistical analysis of shrinkage and distortion. Quantifying the new shape and size of the individual timbers in their dried state is providing critical information for the design of a suitable support system. Several interrelated research projects are underway with Swansea University Department of Engineering in order to design and test various cradles and materials while also examining the widespread problems of deformation and creep currently affecting archaeological ships around the world.

In the case of the Newport Ship, it is envisioned that the extant articulated hull (measuring approximately 25 m long x 10 m wide x 5 m tall) would be reassembled and the missing areas ghosted in ‘digitally’ using a combination of virtual and augmented reality. Such a museum display would have a striking visual impact, much like the displayed archaeological ships Mary Rose and Vasa.

Numerous articles, both scholarly and popular, have been written about the ship project, as well as severaldocumentaries. A comprehensive digital data set has been deposited with the Archaeology Data Service and is free to access (see below). The ship project is currently open to the public on Fridays and Saturdays through the autumn. Major events to mark the 20th anniversary include a summer open day on 30 July 2022 and a one-day conference on 11 October 2022. More information can be found at www.newportship.org.

The Newport Medieval Ship Project is part of the Newport City Council’s Museums and Heritage Service. The project has benefited from a variety of sources of fund over the course of the project, including Newport City Council, Welsh Government, The Heritage Lottery Fund, The Friends of the Newport Ship and numerous others.

Notes

The Mary Rose dating from 1511 and Vasa from 1626 were premier warships respectively of Britain and Sweden. The Newport Ship predates the former by 62 years and the latter by 177 years.

Further/Suggested Reading

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/newportship_2013/

Jones, T. and Panter, I., 2018. The conservation of the Newport Medieval Ship: quantifying post-conservation shrinkage and distortion of PEG pre-treated and freeze-dried hull timbers using contact digitisers, in Proceedings of the 13th ICOM-CC Group on Wet Organic Archaeological Materials Conference: Florence 2016, eds. E. Williams and E. Hocker. pp 338-346. Florence: ICOM-CC WOAM

Nayling, N. and Jones, T., 2013. The Newport Medieval Ship, Wales, United Kingdom. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 43: 239–278. DOI: 10.1111/1095-9270.12053

Nayling, N. and Jones, T., 2014. “Newport Medieval Ship [Data-Set].” Archaeology Data Service. Available from: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/newportship_2013/. DOI 10.5284/1020898.

Nayling, N. and Jones, T., 2018. The Newport Medieval Ship: Archaeological Analysis of a Fifteenth Century Merchant Ship. In: Jones, E. and Stone, R. (eds), The World of the Newport Medieval Ship: Trade, Politics and Shipping in the Mid-Fifteenth Century. University of Wales Press. pp 19-35.