- Author

- Kirsner, Professor Kim, (UWA)

- Subjects

- Naval Intelligence, Ship histories and stories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Sydney II

- Publication

- September 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Kim Kirsner

Kim Kirsner is an Adjunct Professor at the School of Medicine, University of Notre Dame and from 1972-2006 was Professor at the School of Psychology, University of Western Australia. He is a Fellow, Australian Academy of Social Science. He collaborated with Ted Graham, Bob King and Bob Trotter in producing The Search for HMAS Sydney: The Australian Story published in 2014. He has been involved in the search for HMAS Sydney for many years and with this background now brings a fresh analytical perspective to this story which deserves attention.

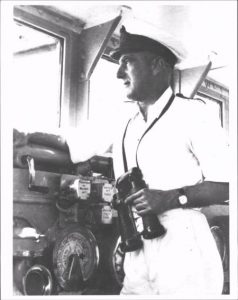

Blame the Captain

The recent launch of The Search for HMAS Sydney: The Australian Story produced further reflection on the performance and the extent of responsibility attributable to Captain Burnett, the captain of Sydneywhen she was lost in action on November 19th, 1941. The motivation to return to the circumstances surrounding the loss of the vessel was underlined by a brief but extraordinary presentation by Bridget Colless (daughter of Joseph Burnett) during our recent book launch at the Australian War Memorial.

The weight of her father’s loss, with the impact of his treatment by the media and historians, were transparent during an exceptionally moving presentation. Perhaps the most challenging moment came when she described the letters received by her mother, abusing her for the loss of other women’s husbands and other children’s fathers. Naval welfare was more or less non-existent in 1941, but it is difficult to imagine even today how the relevant organization would have responded to such a challenge, even if it was aware of it.

Consideration of Burnett’s performance has been touched by two lines of argument. The first of these involves the options not exercised by Burnett on November 19, 1941. These are not in dispute. Rather, the problem is that the options not exercised by Burnett do not exhaust the factors that contributed to the loss of Sydney. The second group of factors reflects the fact that Sydneywas not a lone sailing frigate operating off a distant coast, far beyond the reach of Admiralty. Rather, she was just one part of a complex weapons system comprising approximately 70 cruisers and a vast network responsible for a mass of design, engineering, procedural, training and communication issues and, if these are not on the table, it would be difficult to learn anything from the circumstances surrounding the loss of Sydney. For our purposes, the tension between Sydney as an apparently isolated cruiser and Sydney as one element in a complex weapons system is highlighted by the comparison offered between the performances of Captain Oliver in HMS Devonshire, in her engagement with Atlantis, and Captain Burnett in Sydney, in her engagement with Kormoran. Unless these background or contextual factors are taken into account, the comparison is meaningless.

As matters stand, the stream of historical and legal opinion over the last 70 years has been unforgiving. Historian Hermon Gill1opened the discourse in 1957 with the following:

‘Why Burnett did not use his aircraft, did not keep his distance and use his superior speed and armament, did not confirm his suspicions by asking Navy Office by wireless if StraatMalakka was in the area, are questions that can never be answered.’

Stephen Roskill, a combat veteran, and a champion and historian of the Royal Navy, expressed essentially the same argument, that Burnett was responsible for the loss of Sydney, thus:

‘Captain Roskill’s judgement is that, granted the difficulties of piercing raiders’ disguises, the very close approach made by Sydney during the exchange of signals was certainly injudicious’2

Peter Hore, an RN Historian provided essentially the same assessment,3thus:

‘The lessons were clear: if Burnett had any suspicion at all he should have stayed outside gun and torpedo range’

In 2009, Max Blenkin, a Defence Correspondent, reported the argument advanced by Commissioner Cole in the following unambiguous terms:

Sydneydoomed by captain’s errors of judgment. ‘Almost 68 years after the loss of HMAS Sydney, the first authoritative account of the tragedy sets out the errors of judgment that doomed Captain Joseph Burnett, his ship and 644 crewmen. Never before has Captain Burnett’s responsibility for what happened been expressed in such forthright terms. Terrence Cole, having presided over controversial royal commissions into the construction industry and Australian Wheat Board sales to Iraq, was disinclined to tiptoe around old sensitivities. ‘I am satisfied Captain Burnett made errors of judgment’ he said in his hard-hitting commission of inquiry report. Captain Burnett’s actions appeared ‘almost inexplicable’, he said. ‘But they did not amount to negligence.’4

The conclusion that ‘Captain Burnett made errors of judgment’ is not in contention. However, when the arguments outlined above are extended into the comparison with Oliver, the very different communications provided to the two ships enters the frame, and evaluation becomes more complex. According to Peter Hore, for example, Devonshireimplemented a ‘model engagement’ against the raider Atlantisand destroyed her target at long range (Hore, 2009, p259). Furthermore, Turner, Gordon-Cumming and Betzler (1961), writing 50 years before Hore, adopted essentially the same point of view. According to these authors:

‘In DevonshireCaptain Oliver handled the action with a discretion that, if practiced three days earlier by Sydney, would have saved that cruiser in her duel with Kormoran’(Turner, Gordon-Cumming and Betzler, 1961, p 85)

The second line of argument, involving comparisons between the decisions made by the Captains of Sydney and Devonshire, Burnett and Oliver respectively, is on shaky ground. The critical issue involves the information available to Burnett and Oliver respectively. If they were operating on the basis of comparable information, the comparative analyses noted above would be valid. However, if they operated under qualitatively different conditions, the relevance of the claim that Oliver conducted a model engagement is weakened accordingly.

It may be useful to stand back at this point, and consider changes that have transformed the industrial landscape over the last 70 years.

Human Factors analysis of disasters

The scientific analysis of industrial accidents and disasters has changed out of recognition in the last 70 years. The major change involves the movement away from blame, and towards explanation and understanding and, therefore, learning. The central argument is that only through understanding can we improve performance. There is, I suspect, a measure of tension between the traditional naval model – that Captains accept full responsibility for the loss of their ships – and evolving industrial practice. Industrial practice has moved steadily away from simple blame models in order to facilitate understanding about the causes of industrial disasters, and, by extension, changes in industrial practice designed to minimize risk under a wide variety of design and procedural conditions and practices.

Two more specific issues merit detailed comment. First, inquiries that are judgmental and focused specifically on an individual are likely to overlook organizational and procedural flaws. Second, many errors originate in the same cognitive processes and adaptations that produce skilled behaviour, and they are therefore an integral part of skilled performance.5You cannot have one without the other, so ‘errors’ will always occur. Thus, accidents generally occur because of normal behaviour rather than aberrant behaviour.6

I will illustrate some of these issues by reference to the Piper Alpha disaster in 1988. Piper Alpha (1976 – 1988) was a North Sea oil and gas production platform operated by Occidental Petroleum. On July 6th 1988 an explosion triggered intense oil and gas fires that destroyed the platform, and took the lives of 165 crew plus two people from the rescue crews. There were 61 survivors. Piper Alpha is of particular interest to the search for Sydney for two reasons; first, because the Piper Alpha disasterstands as a beacon on the tortuous road to industrial safety; and, second, because the disaster provided a relatively clear distinction between the people at the Sharp End, most of whom died, and the people at the Blunt End, the owners, designers, managers and instructors in their offices in Aberdeen and Los Angeles.

The chains of errors that contributed to the Piper Alpha disaster are complex. The problems highlighted in Table 1 are only a sample of the critical issues. As indicated above, it is possible to examine the Piper Alpha disaster at two distinct levels. The Sharp End focuses on hands-on errors by the operators and managers on the rig on the day. The Blunt End focuses on engineering, design, training and organizational errors; issues that generally involved earlier and more remote decisions. The distinction between the two ends has obvious parallels in the loss of Sydney. The summary depicted in Table 1 identifies critical decisions that preceded and accompanied the disaster.

Elisabeth Patè-Cornell is Chair of Management Science and Engineering at Stanford University. Whereas the majority of the problems included in the left-hand column can be attributed to individual errors by crew on the oil rig, virtually all of the issues in the right-hand column go to engineering, design, training and organizational issues. Fifty years of research into error analysis have gradually transferred responsibility ‘up the line’ from the person or persons who failed to provide an appropriate report on a pump, to the company and the people who designed the system faced by the operator.

In Paying for the Piper, a film by Prospero Productions, one of the last scenes depicted Ed Punchard – a survivor of the Piper Alpha disaster and a film producer – attempting, unsuccessfully, to access and interview executives from the parent company responsible for the oil well.

| Table 1: Sample of problems revealed by Human Factors analysis of Piper Alpha disaster. Readers are referred to Pate-Cornell7 for a detailed analysis. | |

| Sharp End: between 1200 and 2400 on 6th July, 1988 | Blunt End: Prior to or during the disaster |

| Pressure safety valve removed for routine maintenance but distribution of information incomplete | |

| Active condensate pump stopped and could not be restarted | |

| Inactive and compromised pump switched on, an action that was followed by gas ignition and an explosion. | Design failure: Gas explosion blew through firewall designed to resist fire but not explosion |

| Control room abandoned | Design failure: Lack of provision for destruction of control room |

| Emergency procedures required personnel to move to lifeboat stations | Design failure: Fire prevented personnel from moving to lifeboat stations |

| Design failure: Layout allowed fire to propagate from production modules to critical centres, and destroy control and radio rooms at early stage | |

| Design failure: Location of living quarters, design of topside and safety equipment, blocked evacuation routes, and lifeboats inaccessibility precluded evacuation | |

| Management failure: Costs associated with shut-down precluded actions to terminate flow of high-pressure gas from subsidiary platforms | |

| Management failure: Production levels forced in excess of platform’s design criteria, a point that reflected on the owner, the culture of the oil industry, and the hands-off attitude prevalent in the UK at the time | |

| Technical failure: Water cannon for fire-fighting of limited use because they would injure or kill anyone hit by the water | |

Communication and Procedural considerations

It is possible to identify no fewer than five background or Human Factors issues that touched the loss of Sydney. Consideration of these issues does not exculpate Burnett, but it does place the errors made on the bridge of Sydney in a very different light.

Frequency of close approaches to unidentified vessels. The first consideration is that close approaches to unidentified vessels were common. In the first year of World War II it is possible to identify no fewer than 18 close approaches involving British cruisers or Armed Merchant Cruisers to unidentified enemy vessels. Furthermore, and critically, none of these close approaches, most of which placed a cruiser within 2 nm of an unidentified vessel, had a negative outcome. Most of the unidentified vessels concerned were German blockade runners, however one case actually involved the German raider Atlantis. There were, furthermore, a further 11 cases of close approaches that involved British Q-ships. The actual distances are problematic. In some cases the distance was specified; in other cases it can be inferred from the fact that the unidentified vessel was boarded and captured in the open Atlantic; and in yet another group of cases it can be inferred from the use of pom-pom or machine gun fire to persuade the crew of the unidentified vessel to not abandon ship.

The second year of the war brought several more relatively close approaches to German raiders. HMS Cornwall was down to 4 nm from Pinguin when the latter resolved the Friend/Foe classification problem by opening fire. Similarly, HMS Leander was down to under 2 nm from Ramb I when the weakly armed Italian raider opened fire. The one exception, by HMAS Canberra, involved the destruction of the German supply ships Ketty Brovig and Coburg, but her Captain was subsequently criticized for wasting ammunition, a consequence of the fact that he maintained a range of 9-10 nm for the engagement.

Ambiguity in Admiralty Instructions. The second issue involved the presence of perhaps understandable ambiguity in the Admiralty instructions for dealing with unidentified vessels. According to Captain Ian Pfennigwerth, RAN (Retd.),8for example:

What can be ascertained from German reports is that Sydney was suspicious of Kormoran, which used the identity of the Dutch ship Straat Malakka, but her command team made use neither of the cruiser’s aircraft nor of radio interrogation of the VESCAR system to resolve this identification problem(1). Captain Joseph Burnett of Sydneyand his officers had all the raider intelligence that the system could provide, with the possible exception of the latest WIR (2). Burnett himself had the knowledge gained in his previous posting as Director of the Operations and Intelligence Division of the Naval Staff. Sydney’s actions suggest that she was closely following the instructions of CAFO 143, but she may also have been attempting to board Kormoran in accord with the sense of CAFO 480/1941(3). The final answer will never be known, but had the intelligence system provided Sydneywith sufficient information to perform her role successfully? (italics added). xxx

The numbered and italicized passages are informative.

- No 1 specifies the procedural steps not taken by Burnett; Burnett’s failure to implement these steps is not in dispute.

- No 2 hints at the communication issue considered below.

- No 3 acknowledges an element of ambiguity in the Admiralty instructions; an injunction to not approach a suspect vessel without being confident of her identity cannot easily be reconciled with an argument to board unidentified vessels if the opportunity arises.

Judgement Heuristics. The third issue involves what cognitive psychologists refer to as a judgment heuristic; that is, the ease with which particular instances come to mind. Ease might be determined by recency, where the most recent event generally has an advantage; frequency, where the most frequently occurring event generally has an advantage; or significance, where the decisions that lead to a disaster will stand out relative to other considerations, following the disaster.9A simple analysis of cruiser captain’s decisions during 1941 and early 1942 suggest that the Judgment Heuristic could have been a factor in the sequence of decisions made between February 1941 and March 1942. An obvious hypothesis would involve the following responses to the problems associated with encounters with unidentified vessels (See Figure 1):

- Leander adopted a high risk approach based on the success of close approaches referred prior to the loss of Sydney

- Canberra reacted to the damage to Leander; adopted a low risk approach; and incurred the wrath of the Admiralty, for wasting ammunition

- Cornwall and Sydney reacted to the criticism of Canberra, and adopted high risk approaches, resulting in damage to Cornwall and the loss of Sydney

- Glasgow reacted to the loss of Sydney, classified HMINS Prahbavartias an enemy vessel, and sank that vessel off the coast of India.

- Durban and Cheshire reacted in a different but comparable way to the destruction of Sydney by Kormoran, and Prabhavati by Glasgow, and turned away from night engagements with the German minelayer Doggerbank.

Hindsight Bias. The fourth issue also reflects the Judgment Heuristic referred to above. According to Booth for example,10

‘our knowledge of the outcome of an event unconsciously colours our ideas about how and why it occurred.’

and

‘To the retrospective observer all the lines of causality home in on the bad event; but those on the spot (at the time), possessed only of foresight, do not see this convergence’

Thus, following a disaster such as the loss of Sydney, the information that comes to mind is dominated by the mental considerations associated with the disaster.

Now, when we move back down the road to Burnett on the bridge of Sydney on 19 November 1941, we may note that he had seen no action, so the obvious questionconcerns the most likely memories or ‘mental models’ available to him for decision making. The following might have emerged during the 90 minutes between contact and combat:

- Critique of HMAS Canberra for wasting ammunition at 9-10 nm on the Ketty Brovig and Coburg

- A risky but more or less successful approach by HMS Cornwall to 4 nm from Pinguin, when Cornwall incurred some damage and encountered an engineering problem

- A risky but more or less successful approach by HMS Leander to RambI, when Leander incurred some damage

- Vague impression that numerous blockade runners had been successfully approached in the North Atlantic

- Review VAI to determine what ship Straat Malakka could be

- Admiralty Rules/Guidelines governing contact

- Admiralty Rules/Guidelines governing close approaches to unidentified vessels

According to Hindsight Bias the items in the box encompassing numbers 5, 6 and 7 are critical because, allegedly, Burnett’s failure to comply with them led to the loss of Sydney. Consideration of the problem faced by Burnett at the time might have reflected numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4 however. To the extent that authors reviewing the loss of Sydney have tended to concentrate on the boxed candidates, their reviews may be subject to Hindsight Bias or, as some authors have put it, being ‘wise after the event’.

Communication system supervised by the Admiralty. The fifth and perhaps critical issue involves the role of the communications system supervised by the Admiralty. Did the Admiralty possess information that it failed to communicate to Sydney during the weeks leading up to the disaster? If so, and if the information could have influenced Burnett’s situational awareness for example, interpretation of the loss of Sydney must be reviewed accordingly. Contemporary authors including the Cole Commission and Peter Hore have given benchmark or ‘model engagement’ status to the destruction of the raider Atlantis by HMS Devonshire on 22 November 1941, three days after Sydney was lost. However, the engagement between Atlantis and Devonshire was governed by the fact that Devonshire had received unambiguous but secret intelligence about the location of a scheduled meeting place between Atlantis and two German submarines. Devonshire arrived on the scene expecting to find Atlantis, and she had aircraft up from dawn to ensure detection of the enemy vessel. Combat did not commence until the late afternoon by which time Devonshire had had Atlantis under indirect or direct surveillance for more than eight hours, more than sufficient time to communicate with the Admiralty. In fact, intriguingly, classification of Atlantis proved anything but easy. The CHECKMATE11system was anything but fool-proof in 1941, and Captain Oliver missed a CHECKMATE ‘error’ by only a minute or two. According to Turner, Gordon-Cumming and Betzler:12

‘.. the luck that had accompanied her (Atlantis) cruise had very nearly intervened once more on her behalf. A moment after the signal went out repudiating the claim [of Atlantis] to be Polyphemus, someone at Freetown had misgivings and wrote out a message ‘Cancel my [previous signal]. Ship may possibly be genuine’. But before it could be sent, Devonshire opened fire. An Admiralty document drily remarks: ‘Most immediates’ were flying about the ether for a day or so before the real Polyphemus was located safely in New York harbour’.

Apart from a near-disaster from the CHECKMATE system, the circumstances leading up to the engagement between Atlantis and Kormoran were radically different from those that applied to Sydney, and the comparison is therefore inappropriate. In fact, evidence that Devonshire received information from decryption took decades to emerge, and the success was originally attributed to RN expertise in regard to the sea conditions in candidate re-supply areas in the South Atlantic.

During the 1990’s I purchased Room 39: A study in Naval Intelligence by Donald McLachlan, a member of the Naval Intelligence Division (NID) during World War II. The index to the book does not include any reference to Sydney, and I only recently discovered the following gem buried on page 280,13

‘If one intelligence lesson of the raider campaign is the amount of information that can be built up from small bits of apparently unrelated details, the other is that letting one’s own forces know what has been learned about the enemy is just as important. Promulgation – that is to say the passing on – of intelligence was quite often slow or incomplete, either because of excessive secrecy or because of the sheer administrative difficulty of reaching ships all over the world. There is no doubt that the casualties – for example, the loss of the cruiser Sydney – from raider action might have been substantially smaller if what was known about them had been circulated more fully and swiftly’.

McLachlan served on the personal staff of the Director of Naval Intelligence from 1940 to 1945, and he was writing in the years before the absolute ban on publication of anything to do with cryptography was lifted. Sadly, that is all we know, because the British Ministry of Defence removed the balance of the papers deposited by McLachlan at Churchill College after his untimely death in 1971. I suspect that that is all we will ever know, officially!

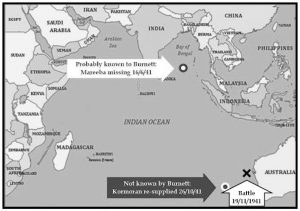

My best guess as to the missing information draws on the scholarship of Barbara Winter. It is evident from her book14that the German supply ship Kulmerland sent a short-signal to Germany stating that ‘SUPPLY SHIP DETACHED RENDEZVOUS 17TH DAY FOLLOWING MONTH SCHIFF 41’.

In summary, the NID knew the location of Kormoran near the coast of Australia on October 26th (about 800 nm off the coast as illustrated in Figure 2) and they would or should have assumed that she had been re-fuelled and re-supplied during an extended 10-day meeting with Kulmerland. A signal to cruisers engaged in convoy protection would surely have provoked an appropriate state of situational awareness.

The latest information about raiders available to Burnett probably involved the disappearance of the merchant vessels Mareeba and Velebit off the Maldive Islands five months earlier. The raider responsible for these actions – if raider it was – could have been off Murmansk or Vladivostok by late November. Furthermore, there is evidence that the Admiralty transmitted information derived from signal decryption to both Devonshire, to guide the search for German raider Atlantis, and Dorsetshire, to guide the search for the German supply ship Python, then in the process of shipping survivors from the Atlantis back to Germany. Thus, for Devonshire,15

‘November 13th: Consequent on decryption of ENIGMA traffic (Devonshire was) deployed for the interception of German commerce raider ATLANTIS known to be operating in South Atlantic and also providing fuel for U-Boats.’

And Dorsetshire,16

‘November 11th: Deployed for search for German commerce raiders ATLANTIS and U-Boat Supply ship PYTHON, known to be operating in Atlantic (Note: These movements had been the result of interception of signals and decryption of ENIGMA at Bletchley Park.)’

‘December 1st: Sighted German U-Boat supply ship PYTHON with submarines UA and U68 alongside.

Submarines departed and made torpedo attack which failed. PYTHON scuttled.’

Radio silence in November 1941 was not therefore a critical issue.

Consideration of the organizational and communication issues does not absolve Burnett of responsibility for the loss of Sydney, but it does underline the fact that Sydney was part of an essentially British weapons system, and that a measure of responsibility rested with the Admiralty as well as Burnett.

In conclusion, it is not my intention to remove responsibility for the loss of HMAS Sydney from Captain Joseph Burnett. Rather, it is to argue that the focus on Burnett has enabled us to avoid a number of uncomfortable issues. Perhaps the most disconcerting of these involves the decision by the Admiralty to not inform the Australian station about the known proximity of Kormoran to the West Australian coast in November, 1941. A second involves the role of Hindsight Bias in historical review, a factor that can distort interpretation of accidents and disasters in ways that do no credit to people who have given their lives for their country. But perhaps the most disconcerting problem of all concerns the extent to which undue focus on blame can draw our attention away from the complexity and ambiguity of combat environments, and limit our learning opportunities accordingly.

1 Gill, H. (1957, 1985). Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942, Collins in association with the Australian War Memorial.

2 Turner, L.C.F., Gordon-Cumming, H.R. & Betzler, J.E. (1961). War in the Southern Oceans 1939-1945. Page 85.

3 Hore, P. (2009). Sydney, Cipher and Search. Seafarer Books. WS Bookwell. Finland. Page 255.

4 Max Blenkin: AAP: August 14th, 2009.

5 Myles-Worsley, M., Johnston, W.A. & Simons, M.A. (1988). The influence of expertise on X-Ray image processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 14, 553-557.

6 Green, M. (2004). Nursing Error and Human Nature. Journal of Nursing Law, 9, 37-44.

7 Patè-Cornell, E.P.C. (1993). Learning from the Piper Alpha Accident: A Post-mortem Analysis of Technical and Organizational Factors.Risk Analysk, 13 (2), 215-232.

8 Pfennigwerth, I. (1971). Missing Pieces: The Intelligence Jigsaw and RAN Operations from 1939-1971. Papers in Australian Maritime Affairs, No 25. Sea Power Centre Australia.

9 Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability.Cognitive Psychology, 5 (2), Pages 207–232

10Booth, R. (2011). How Hindsight Bias distorts history: An iconoclastic analysis of the Buncefield explosion. HASTAM. http://www.hastam.co.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/hindsight-bias-full-2012.pdf

11The CHECKMATE system was used by the RN for ship identification during World War II. The system depended on reference to the Admiralty in London, and became fully operational during 1943.

12Turner, L.C.F., Gordon-Cumming, H.R. & Betzler, J.E. (1961). War in the Southern Oceans 1939-1945. Page 103.

13McLachlan, D. (1968). Room 39: A study in Naval Intelligence. Athaneum; New York. Page 280.

14Winter, B. (1984). HMAS Sydney: Fact, Fantasy and Fraud. Brisbane; Boolerong Press. Page 113.

15Mason, G.B. (2003).Service Histories of Royal Navy Warships in WORLD WAR 2. HMS Devonshire– County-type Heavy Cruiserincluding Convoy Escort Movements, Edited by Smith, G. Navy History Homepage.

16Mason, G.B. (2003).Ibid.