- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

A shipping venture to service the Australian colonies had unforeseen consequences for gold miners who had struck it rich and were returning to their homelands with wealth. After nearly two months at sea in a modern well-found ship and only hours from their destination, disaster struck. This now long-forgotten story is listed as the greatest maritime tragedy to befall the Australian colonies, although it occurred far from our shores.

Gibbs and Bright form an alliance

Gibbs, Bright & Company was established at Bristol in 1818. The Gibbs family made its fortune as wool merchants, trading cloth to Spain and importing fruit and wine. The family also established a monopoly on the import of guano from Peru for fertiliser and this success led to the establishment of a merchant bank called Anthony Gibbs & Sons. The Bright family-owned sugar-plantations in Jamaica and a connection between the two families was established through their West Indies trading. During the gold rush era the interests of Gibbs & Bright extended to the Australian colonies.

When the company began to acquire ships for the Australian trade they did this with a flourish, first purchasing Brunel’s wonder ship Great Britain which was the largest ship afloat when launched. However, after running aground and needing extensive repairs she was not a financial success. Always seeking a profit,

Gibbs & Bright bought her at a bargain price. Refitted and with new engines she sailed for Australia in August 1851, and a month later the clipper Eagle sailed for Port Phillip. The acquisition of Albatross followed, and in August 1852 she landed the first shipment of gold from the New South Wales gold fields, valued at £50,000.

The Liverpool and Australian Steamship Navigation Company

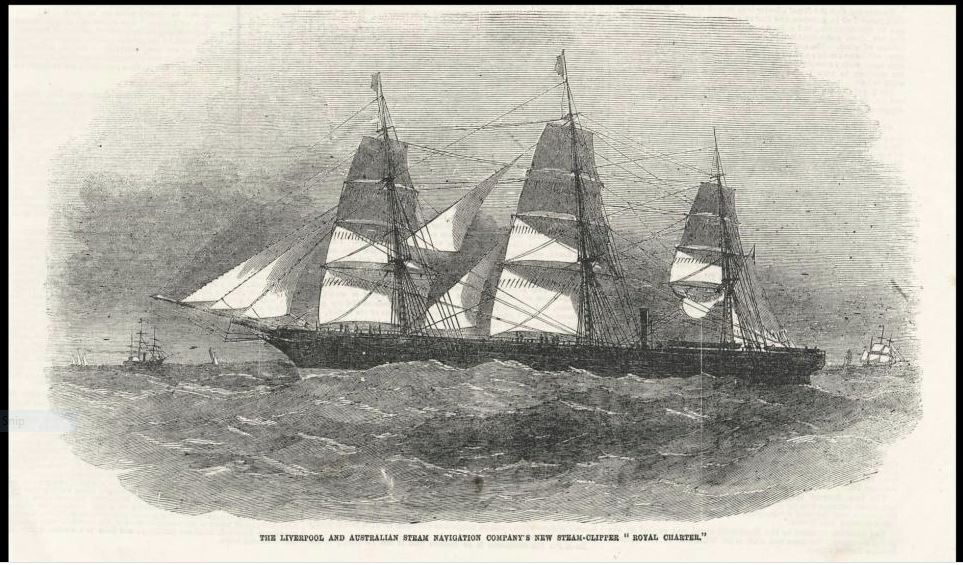

Their next acquisition was another bargain. She was the steam clipper Royal Charter, laid down by Sandycroft Ironworks at Deeside in North Wales. When Sandycroft became bankrupt the ship was bought off the stocks by Gibbs & Bright. After completion she entered service in April 1855, registered under the name of the Liverpool and Australian Steamship Navigation Company, by which time the company had eight vessels on the Liverpool to Australia run.

Royal Charter

Royal Charter was a new type of ship, an iron-hulled steam clipper built in the same way as a traditional sailing clipper but with an auxiliary steam engine which could be used in the absence of suitable winds. She was 2719 gross tons, 236 feet (72 m) in length, with a 39 foot (12 m) beam. She had one boiler servicing a 200 horse power direct-acting steam trunk engine, driving a single propeller. She could carry up to 600 passengers, those in first class in some luxury. The company offered a fast 60-day passage from Liverpool to Australia from £14.

Royal Charter soon developed an enviable reputation as being one of the finest vessels on the Australian run. She was a magnificent ship that in favourable conditions could reach a top speed of 18 knots and with internal appointments to rival that of London’s west-end hotels. Such was her success that her cabins were at a premium.

While the expanding business mainly involved taking thousands of emigrants from the British Isles to the new gold diggings there was a reverse trade, mainly taking successful miners who had struck it rich back to their homeland, together with their families. On one of these return voyages which began in Melbourne on 26 August 1859 Royal Charter was carrying 388 passengers and a crew of 112, a total of exactly 500 souls. The ship was also carrying gold bullion valued at £322,440 and an estimated £150,000 in gold sovereigns belonging to the passengers. Part of this amount was lodged in the strong room but many passengers preferred to use money belts for safe keeping.

The Royal Charter Storm

After travelling non-stop around Cape Horn, on 25 October 1859 they briefly called at the Irish port of Queenstown (Cobh), where mail and thirteen of the passengers were landed via the pilot boat. After leaving port they spoke to the steam tug United Kingdom with eleven riggers on board, bound for Liverpool. Captain Taylor kindly agreed to take them aboard, saving the tug the journey. Royal Charter now had 498 persons on board.

Royal Charter was nearly home and making her way up the Irish Sea when a gale struck. The master Captain Taylor was proud of his ship, his seamanship, and his timekeeping, and had told his passengers he would have them in Liverpool that evening. The opportunity could have been taken to turn back to shelter at Holyhead but this would lose time, a not desirable option when captains of crack ships were given considerable bonuses to reduce passage times. This may have encouraged a philosophy of speed being placed before safety.

Upon reaching Point Lynas a signal gun was fired calling for a pilot to take them on the final phase of their journey to Liverpool. But with the storm still raging to Force 10 and increasing it was impossible for the two pilot boats on station, which were being tossed about like matchsticks, to make the rendezvous. Likewise, later that evening the coxswain of the local lifeboat and his crew refused to launch their boat since this would be condemning them to almost certain death, such was the violence of the storm.

When the wind reached Force 12, and with her propeller having little effect, the ship was out of control. At 11.00 pm the decision was made to drop the port anchor but as she continued to drift inshore the starboard anchor was let go. Early the next morning at 1.30 am the port cable snapped and an hour later the starboard cable parted; now the masts were cut down to reduce drag. The great clipper was then taken by the raging seas and dashed against jagged rocks where she broke up only 50 yards from the shore.

The conditions were such it was impossible to launch a boat but one of the crew, Maltese born Guzi Ruggler, managed to swim ashore with a line, enabling a few to be rescued by bosun’s chair, and a few others struggled through the surf. But most died from being dashed against the rocks, many weighed down by their money belts. The Militia were called in to help with the recovery of bodies, their identification and burial, and to prevent looting. Despite these precautions golden sovereigns were washed inshore, with the sand making some locals mysteriously rich. There were only 39 survivors, made up of 21 passengers and 18 crew; no women or children were saved. Most bodies were buried in local churchyards, with a memorial raised at Llanallgo where the largest number of 140 was laid to rest.

Almost immediately intensive salvage work was undertaken by divers employed by Gibbs & Bright and after four months had recovered all but £30,000 from her bullion. The owners were criticised for focusing on the retrieval of bullion instead of assisting with the recovery of bodies. The wreck was eventually sold to a local consortium who found a further 500 sovereigns.

The storm, which was one of the most powerful recorded in the British Isles, accounted for the loss of 113 vessels and another 90 severely damaged, plus over 800 lives lost. The hurricane became known as the ‘Royal Charter Storm’. The disaster had the effect of further development of the Meteorological Office, then under the control of Captain Robert FitzRoy, RN. He produced a detailed report to prove that the storm could have been tracked and predicted. Through this analysis FitzRoy demonstrated the validity of his models leading to a weather forecasting and storm warning service. To help prevent similar tragedies a weather forecast for shipping services around the British Isles was established in February 1861, using telegraph communications.

The moment news of the disaster reached London and Liverpool, agents from Lloyd’s and the owners of the ship were despatched to the scene. They were accompanied by representatives of the principal London and Liverpool journals. Charles Dickens visited and described the disaster in his weekly magazine All the Year Round. This account was later reprinted as the first chapter in his book The Uncommercial Traveller, and it says:

So tremendous had the force of the sea been when it broke the ship, that it had beaten one great ingot of gold deep into a strong and heavy piece of her solid iron-work: in which, also, several loose sovereigns that the ingot had swept in before it, had been found, as firmly embedded as though the iron had been liquid when they were forced there.

The Inquest and Inquiry

An inquest commenced in the Llanallgo schoolroom on Tuesday 2 November 1859 before Mr William Jones, coroner for Anglesea, supported by a jury of local men, witnessed by two magistrates and attended by a solicitor acting for Gibbs & Bright. The inquest was not entirely satisfactory as it was conducted in English and after being recorded it had to be translated into Welsh for the benefit of the mostly Welsh speaking jurors.

On the Friday evening the jury came to a verdict, having found that the wreck of the Royal Charter was caused by purely accidental circumstances; that Captain Taylor was perfectly sober and that he did all in his power to save the vessel and the lives of the passengers.

The inquest was followed by a Board of Trade inquiry which opened in Liverpool on 15 November before Mr J. Mansfield, stipendiary magistrate of Liverpool, and Captain Harris RN, a nautical assessor. Some of the sad facts which marked the loss of this ship, in which her captain and all her officers perished, were brought to light. However, by the end of the inquiry the court was satisfied that the ship and its equipment had been in good condition and carried an adequate supply of coal (fuel) at the commencement of the storm. They concluded that the captain and officers had done all their duty demanded to try and save the ship and those aboard her.

The press however was not convinced, being of the opinion that the investigation had been feebly conducted. More demanding questions could have been asked regarding the options available and the courses of action taken leading to this disaster which claimed the lives of four hundred and fifty-nine men, women and children.

Some Observations and What Remains

What is remarkable about this tragic event is the speed of action that took place over 160 years ago in times of primitive communications. The ship, completing its voyage half way around the world, primarily under sail, was remarkably fast. So too were subsequent actions after she was wrecked. Within days the Militia had been called out, bodies recovered, identified and buried, salvaging was underway, and a Coronial and Board of Trade investigations called when witnesses were still available with fresh memories. The system may have been less rigorous than expected but they did reach a conclusion. Compare this to the present, with almost instantaneous communications but complicated by layers of bureaucracy, consultants, lawyers and public relations experts, when decisions would now take not days, but years.

Today the remains of the wreck lie close inshore in less than five metres of water and are uncovered by shifting sands at certain times of the year. A few gold sovereigns and other items have been discovered by scuba divers over the years. In 2012 a prospector found what is believed to be Britain’s biggest gold nugget (albeit Australian) at 97 grams (3.4 oz.) but rather unsportingly the Receiver of Wrecks took possession of it on behalf of the Crown.

References:

Fowler, Frank, The Wreck of the Royal Charter, Sampson Low, London, 1859.

Gater, Dilys, Historic Shipwrecks of Wales, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, Wales, 1992.

Hamer, Gillian E., The Charter, Self-Published, North Wales, 2012.

Heaton, J. H. (Ed), Australian Dictionary of Dates & Men of the Time, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Jones, Ivor Wynne, Shipwrecks of North Wales, Landmark Publishing, Ashbourne, Derbyshire, 2001.