- Author

- Sullivan, John

- Subjects

- History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- July 1992 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

On 12th February 1841, Torrens boarded ‘Ville de Bordeaux’ to examine her papers, and two days later an order signed by Governor Gawler directed the ship into Port Adelaide so that unspecified suspicious circumstances might be investigated. Whilst the master was not aboard, the crew was persuaded to sign Articles to work under Customs Officers during the short passage to Port Adelaide. On the morning of 21st February two Customs Officers, Anthony and Lockyer, went on board to take charge of the vessel and sail her to Port Adelaide. The captain was now on board, and he was preparing to sail – but not for Port Adelaide! He requested the Customs men to return to shore, but they refused, as their orders called for them to take charge of the ship. ‘Ville de Bordeaux’ therefore settled with the Customs men on board, and the next day she was seen heading down the Gulf with all sail set.

The only steamer in the area was the paddle steamer COURIER, and Torrens, together with the Harbour Master and a part of armed police, set off in pursuit in ‘Courier’ on the afternoon of the 21st. It was not thought ‘Courier’ would catch ‘Ville de Bordeaux’, which was a very fast vessel because of her original design as a warship.

In the event, it seems that the crew persuaded the master to bring ‘Ville de Bordeaux’ back to Port Adelaide, partly because she was not fully provisioned, but no doubt they were also influenced by the Articles they had signed.

The ‘South Australian Chronicle’ published several editorials over the next few months, in which the actions taken by Torrens were vilified. In the issue of 24th February 1841, the seizure of ‘Ville de Bordeaux’ by the Customs officials was described as ‘gross and piratical, unprecedented and illegal’. The paper forecast a visit by a French warship to reclaim ‘Ville de Bordeaux’. On 9th June, 1841, the paper called for the Collector of Customs and the Advocate General to be dismissed from office because of their ‘amazing actions’ in the matter.

Now we come to the visit of the French corvette ‘L’Heroine’, so accurately predicted by the ‘Chronicle’ more than a year earlier. On the morning of 9th March, 1842, the residents of Glenelg woke to find ‘L’Heroine’ at anchor in Holdfast Bay. Whether the corvette had orders to open fire is a matter for conjecture, but certainly Captain L’Eveque, in command, did not pay the usual formal calls on Government officials which were expected from the commanding officer of a visiting warship belonging to a foreign power. Cooper, in his book from which Lew Lind obtained the entry under 9th March, does not refer to ‘L’Heroine’ as having her guns out, but he does confirm that she was in Holdfast Bay (not off Port Adelaide) and that she was not inclined to be friendly. Maxwell in his book ‘Wooden Hookers’ describes ‘L’Heroine’ as a 28-gun frigate with her ‘guns conspicuously set’, which could be interpreted as being run out. Parsons records the visit of ‘L’Heroine’, but apart from referring to the lack of official calls by L’Eveque, he gives no indication of just how war-like she seemed. ‘L’Heroine’ sailed off after eighteen days when it was obvious her demands would not be met. As a matter of interest, M. Joubert, the owner of ‘Ville de Bordeaux’ was on board ‘L’Heroine’ all the time she was in South Australia waters.

Mr Brian Samuels, of the History Trust of South Australia, says that the claim that ‘L’Heroine’ held the Port to siege is probably a gross overstatement. Certainly the local populace did not think she would open fire, as England and France were not at war. The locals flew the English and French flags side by side in an endeavour to convince the French not to fire, but if L’Eveque had opened fire, perhaps England and France would have been back at war. Perhaps this, more than anything else, influenced L’Eveque to sail away without having achieved his object. The ‘Chronicle’, during the time that ‘L’Heroine’ was at Glenelg, recorded the arrival and departure of many ships, so it would seem the Port was not really under siege.

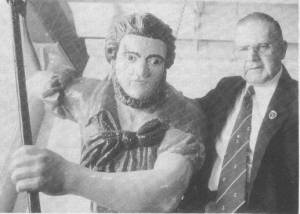

Returning to ‘Ville de Bordeaux’, Joubert eventually received a satisfactory payment for his ship, but the obstinacy of Torrens cost the South Australian government a great deal of money, which the infant colony could not afford. ‘Ville de Bordeaux’ never left Port Adelaide. She was stripped down and used as a lightship for a few years, until one H.C. Fletcher bought her in 1852 for use a coal hulk. In 1865 the hull was broken up, but the figurehead, a man wielding a harpoon, remained in Fletcher’s yard for the next sixty years. It then went to the Port Adelaide Nautical Museum. In recent years it was fully restored by Captain Gillespie, and it is now located in the South Australian Maritime Museum (also at Port Adelaide) in what is claimed to be the finest collection of sailing ship figureheads in Australia.

Finally, and coincidentally, the paddle steamer ‘Courier’, which was involved in the chase after ‘Ville de Bordeaux’, also ended her days as a lightship near Adelaide. The visit of ‘L’Heroine’ probably helped the South Australian government decide to build forts at Glanville and Largs, even though that decision was not reached for another 36 years!