- Author

- Pacini, John

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

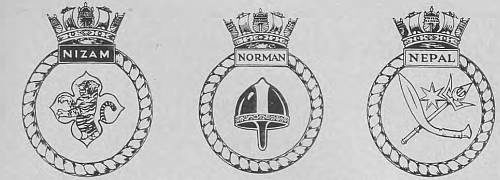

- HMAS Quickmatch, HMAS Napier, HMAS Nepal, HMAS Nizam, HMAS Quiberon

- Publication

- September 1974 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

War correspondent John Pacini was in Napier when he wrote this article in 1945. The Allied Fleets were steaming for Tokyo and World War II was in its last days. Pacini, during his sojourn in Napier, shared the cabin of Lieutenant ‘Buster’ Crabb, who was later to rise to flag rank. The ‘N’ class destroyers were returned to the Royal Navy some six months later.

Lt. Commander W. F. Cook, RAN, commanding HMAS Nizam.

Commander J. Plunkett-Cole, RAN, commanding HMAS Norman.

NO TRUER PHRASE has been concocted than ‘a destroyer is a maid of all work’. In what was a short period at sea the Napier did convoy duties, helped in exercises with elements of the British Pacific Fleet, delivered supplies to ships, transferred hospital cases to the hospital ship during day and night (under blackout conditions and almost entirely by moonlight), distributed secret messages, helped to screen the carrier strike force during its attack on Japan, delivered mail, and dozens of other smaller tasks.

Despite their comparatively heavy armament, one feature of the ‘N’ Class destroyer prevented them from immediately accompanying larger elements of the British Pacific Fleet, including the four carriers, into the strike area. Apparently the high naval authorities considered that the great carriers were protected well enough by anti-aircraft weapons and, therefore, chose the Australian destroyers with the best fuel endurance – the two ‘Q’ Class destroyers Quickmatch and Quiberon, both manned by Australians, because they carried 100 tons more fuel than the ‘Ns’.

Constant requests by Captain Buchanan, however, to join the strike force eventually bore fruit and the Napier accompanied the last six strikes against Japan, including one which was made on the morning of August 15, but which was recalled when news of cessation of hostilities reached the Fleet. On the last few strikes the Nizam came along, too. The honour of being the first Australian ship in Jap home waters goes to Nizam. Just before peace was declared Nizam passed a ship moving between Manus and the strike area, showing lights four miles away from just before dawn. The Nizam challenged the ship, but received no answer.

At first light the Japanese ensign was seen on the masthead, and large Red Cross signs were painted on the craft. On further questioning it alleged that its identity was hospital ship Kiku Maru, but Lieutenant Commander William Cook, RAN, of Victoria, the captain of Nizam, sent a boarding party from his ship to investigate.

The boarding party landed on the hospital ship by whaler, and established visual communication aboard. The party was told that the ship had accommodation for 100 patients. It had none aboard at the time. None of the boarding party spoke Japanese, nor was the Japanese captain able to speak English very well, but was able to explain with the aid of a Japanese-English dictionary that his ship was destined for Marcus Islands. The dictionary did not help our boarding party to translate the ship’s log.

In its report the Nizam said that matting mattresses, apparently used for sick Japanese, were two inches thick, and laid on the deck. No operating theatre existed, and only one small operating table was found. The hospital ship had also one refrigerator, and no supply of blood serum or plasma was seen. The ship itself was clean and members of its crew quite hospitable. The commanding officer of the boarding party was offered a bottle of saki as a gesture, but refused it.

A few days later an American destroyer boarded another Japanese hospital ship, and found arms and ammunition aboard.

Another interesting sidelight of the part played by Australian destroyers in their last hostile tour of operations concerned the hospital ship Tjitjalenka, which was attached to the British Fleet. Tjitjalenka was a Dutch ship, but all its medical staff – doctors and nurses – were English. Because of the sudden changes of position for the fuelling area rendezvous and the fact that under Geneva conventions hospital ships can only be within a certain distance of warships, every now and then some destroyer had to go out, find the hospital ship, and give it the disposition of the new rendezvous by hand signal.