- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2016 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Dr. Carlos Tromben-Corbalán, Centre for Strategic Studies, Chilean Navy

Tuesday 30 August 2016 was an auspicious day in the Chilean naval calendar marking the centennial of the rescue of members of the Trans-Antarctic Imperial Expedition led by British explorer, Sir Ernest Shackleton. After three previous unsuccessful attempts, the rescue, made in adverse conditions, by the crew of Yelcho, a small cutter commanded by Luis Pardo-Villalón1is a remarkable achievement. By way of introduction, readers might benefit from biographical detail of the two main characters involved in this dramatic rescue.

Luis Pardo-Villalón

Luis Pardo was born in Santiago, Chile on 20 September 1882. His grandfather was a veteran of the Chilean War of Independence and his father an Army officer during the border conflict against Perú and Bolivia.

Aged eighteen, Luis commenced training as a merchant marine officer in the navy-run training school at Coquimbo, a fine natural harbour in central Chile. Graduating in June 1903, he made his first deep-sea voyage in a barque bound for Germany.

Three years later, on 27 June 1906, Luis entered the Chilean Navy. At this time, merchant mariners were required to serve in auxiliary ships because the naval academy was unable to satisfy its needs. These officers maintained their mercantile ranks while undertaking naval service. Soon afterwards, Luis married Laura Ruiz-Gaspar, and the union produced three boys and a girl. Continuing the family tradition of military service, the two eldest sons joined the air force.

Promoted Second Mate in 1910, Luis served in several naval vessels. After the 1916 Antarctic rescue, he received promotion to First Mate and in 1917 transferred to the submarine tender Angamos,when Chile acquired its first submarines, participating in the inaugural voyage of this flotilla.2Early in WWI two dreadnoughts building in Britain for Chile were requisitioned by the Admiralty, in partial compensation five H-class submarines building in the United States for Britain were transferred to Chile and a sixth boat was purchased directly by Chile.

At least two authorities confirm3that an offer of £25,000 in prize-money was made to Luis Pardo for his Antarctic rescue, but this he refused, saying he was only completing his duty. Today this would today be worth £1.5 million or US$2.2 million.

After retiring from the Navy in May 1919, Luis was appointed, as his country’s consul, to the busy commercial centre of Liverpool, England.4Here he maintained contact with Lady Shackleton and some of those rescued. He attended the 1930 London Polar Exhibition and was present at the Royal Geographical Society dedication of Shackleton’s statue.

In 1932 Luis and his family returned home. He died at Santiago, on 21 February 1935, at the early age of fifty-three.

Ernest Henry Shackleton

Ernest Shackleton was born in County Kildare, Ireland on 15 February 1874. When he was ten, his family moved to London. On leaving school at sixteen, he became an apprentice in a sailing ship. His first trip was to Chile via Cape Horn facing severe storms amid the austral winter. Years later, in answering a journalist’s question, he said his first idea of becoming an Antarctic explorer came during that voyage.

Upon completing his apprenticeship, he remained in the merchant service eventually gaining a master mariners certificate. During the Boer War, while serving in a troop transport, he met an Army officer whose father was financing an Antarctic expedition. Due to this encounter, he joined the expedition and received a commission as a Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal Navy Reserve.

The expedition used Discovery captained by Commander Robert Falcon Scott, RN. This ship was specially designed to operate in polar regions. The voyage started from London on 31 July 1901 and for Shackleton finished in September 1903 as he was evacuated from Antarctica due to illness. During this expedition Scott, Shackleton and a third member reached a point located 463 nm (858 km) from the Geographical South Pole. In the following years, Shackleton worked as a journalist and advisor to other polar expeditions.

In 1907, he was successful in attracting financial support from industrialists for a new expedition. The voyage under his command started on 1 February 1908 in the ship Nimrod.Again, the goal was the Geographical South Pole. After a long land transit, his expeditionary party reached a point 97 nm (180 km) from the Pole. However, they sensibly returned due to shortage of food. Nevertheless, he had gone further south than any other man. He was now a celebrity, becoming Sir Ernest Shackleton. The following years as a conference speaker he worked hard gathering financial resources for another expedition.

Following this expedition, Shackleton and his colleagues returned to their homelands, some joining Imperial forces for the remainder of the First World War. Sir Ernest obtained an Army commission and with the rank of major served in Russia in 1919 as Director of Arctic Supplies and Transport. In 1921, he started his final Antarctic expedition, when at South Georgia on 5 January 1922 he died of a heart attack, just short of his 48th birthday. At his wife’s request, he lies buried at this lonely outpost.

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition – Endurance and Aurora

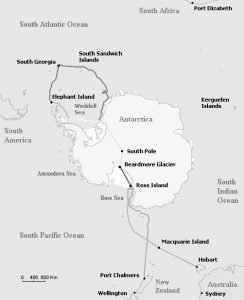

A future expedition depended on the results of those initiated by the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, and the aforementioned Robert Scott, both competing as first to reach the South Pole. Amundsen achieved this accolade on 14 December 1911. Thirty-five days later Scott also arrived at the Pole, but Scott and his team perished during the return journey. The results of these expeditions moved Shackleton towards a more ambitious attempt at transiting the continent. He planned to land on the shores of the Weddell Sea and cross this vast land at its narrowest place through 1500 nm of snow and ice via the South Pole to embark in another ship based in the Ross Sea (McMurdo Sound). Financial backing was obtained from the British Government and private donors.

Shackleton selected fifty-six mariners and scientists of different nationalities. Divided into two groups, one embarked in Endurance5 bound for the Weddell Sea. The second group used Aurora,6which would recover those crossing this continent on their arrival at McMurdo Sound. The crew of Aurora also established supply depots from McMurdo to the South Pole supporting those transiting the continent.

The beginning of the First World War did not stop the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, which set out for the Weddell Sea in August 1914. After some days at the island of South Georgia, Endurance sailed through pack ice until trapped on 19 January 1915, never to extract herself from this vice like grip.

Aurora departed from Hobart, Australia in December 1914. Delay was experienced on encountering sea ice in McMurdo Sound but she managed to make her way further south and then send parties ashore establishing cross continental supply depots. In May 1915, she also was trapped in ice and carried out to sea, stranding those setting up the supply depots. She remained trapped for the better part of a year, drifting some 1600 nm. It was not until 12 February 1916 that she escaped the deathly embrace and reached Dunedin, New Zealand on 3 April 1916.7

The situation in Endurance was if anything worse, when pressure increased on her hull she began taking on water. The crew were forced to abandon ship, taking with them essential equipment and supplies and three boats. Endeavour finally sank below the ice on 21 November 1915. The crew remained camped on the frozen floe expecting the drift to take them to Paulet Island, but this did not happen.

On 19 April 1916, as the ice floe started breaking up, they boarded their open boats and made for Elephant Island. Since this island was uninhabited, and remote from the now seasonally closed whaling grounds, Shackelton decided to leave his men camped on its northern coast. The shelter comprised two boats placed upside down on top of stone bases and covered with canvas saved from the sails. Shackleton then used the third and largest boat named James Caird to go with five other explorers to South Georgia, 800 nm (1,480 km) distant. The voyage took 17 days through stormy seas arriving at King Haakon Bay on 16 May 1916.8

Chilean Navy Ship Yelcho

Early in the 20th century, the Chilean Navy had several cutters used in explorations, lighthouse supply and hydrographical work. They also supported isolated settlements, mainly in southern parts of the country. This remote region, of islands, channels and fiords suffers extremely inhospitable weather from April to November. Some of these ships were operated by Dirección del Territorio Marítimo(Coast Guard), also part of the Navy.

The cutter Yelcho was purchased by the navy in 1908. Two years earlier, she was built in Glasgow as a tug for private operators in southern Chile. Displacing 480 tons she was120 feet (36.5 m) long, with a 23 feet (7 m) beam and could make10 knots.

The propulsion system consisted of a cylindrical boiler supplying steam at 120 pounds per square inch (8.3 bar)9with a compound engine driving a single four bladed propeller. She was coal fired, without electric lighting, radio communications or heating. The steel hull had a low freeboard and without double bottom tanks, she presented serious limitations when sailing into stormy seas and uncharted waters. The single propeller was also at risk from pack ice. Two other similar cutters lost their propellers due to uncharted rocks during hydrographical surveys. One of them, with a few tools, manufactured a propeller onboard, because it was unlikely she would be found without radio.10

Fortuitously, between April and May 1916, before the rescue mission, Yelchounderwent a hull refit in a private dockyard with the naval maintenance shops at Punta Arenas overhauling her engine.

In 1945, Yelcho was transferred to the naval base in Talcahuano. She operated between this port and Quiriquina Island, inside Concepción Bay. Used as a tender, she served the Seamen Apprentices School located on this island until decommissioned in 1958.11Yelcho’s bow is now a monument near the Chilean naval base at Puerto Williams on the Beagle Channel.

The Rescue

Shackleton and his party arrived where the wind and currents took them to King Haakon Bay. They made a shelter similar to that at Elephant Island by placing James Caird in an inverted position. After a few days recovery they needed to find help by proceeding to the inhabited side of the island, 50 km distant over treacherous and previously un-climbed snow covered mountain ranges.

With favourable conditions, at dawn on 19 May Shackleton and two companions set out crossing the daunting South Georgia landscape. They left behind three men in their improvised shelter. After two days fighting over snow covered mountains, they arrived at Stromness Bay whaling station. Their first concern was to send a craft to rescue their three comrades from King Haakon Bay. This mission, accomplished by the whaler Samson,ended happily when James Caird was towed into Stromness on 22 May.

The second urgent action was finding a ship to reach Elephant Island and rescue the remainder of Endurance’s crew. Shackleton chartered the 206-ton steel-hulled steam whaler Southern Sky. Since the whaling season had finished, the engines needed coaxing into action and the ship re-supplied. The Southern Sky’s passage started auspiciously but, on the third day, pack ice12prevented the ship getting nearer than 75 nm (139 km) from the marooned survivors. With increasing ice and fuel shortage, they returned to the closer Falkland Islands for coal.

Upon arrival, Shackleton telegraphed several countries seeking help in rescuing his men. Britain was supportive but did not offer a solution, probably because of wartime emergencies. Norway and the United States offered assistance taking several months, by which time the survivors, already short of food, would starve.

Nevertheless, the Uruguayan Government offered the 80-ton trawler Instituto de Pesca No. 1. This vessel departed Montevideo on 9 June 1916, calling at Port Stanley (Falkland Islands) to embark Shackleton, Worley and Crean (formerly officers in Endurance) on 16 June. The next day they set sail for Elephant Island but again pack ice hindered the approach when only 25 nm (45 km) from their destination.

Upon returning to Port Stanley, they met the cruiser HMS Glasgow, the lone British survivor from the November 1914 Battle of Coronel who found retribution one month later at the later Battle of the Falkland Islands. Regrettably, the Admiralty overruled an offer of assistance by her captain. However, Shackleton had a lucky break meeting Vice Admiral Joaquín Muñoz-Hurtado taking passage from Britain in the liner Orbita to assume command of the Chilean Navy.

Shackleton persisted, also sailing in Orbitato Punta Arenas. Here help was forthcoming by British residents chartering the diesel powered 60-ton trawler Emma. To save fuel, the twenty year old Emma was towed by the naval cutter Yelcho under command of First Mate Francisco Miranda-Bórquez. The voyage started at midnight on 12 June but storms prevented the use of the Beagle Channel and the ships had to sail the much longer Magellan Strait. Then Yelcho experienced engine problems, sheltering at a small inlet for repairs. The ships set out again and close to Staten Island Yelcho transferred Second Mate León Aguirre-Romero who had volunteered for the rescue operations, to Emma13. Aguirre was experienced in sailing the Southern Ocean and those later rescued praised his personal and professional qualities.14

Yelcho towed Emma for 50 nm to open waters, when the trawler started out alone to Elephant Island. Initial good weather quickly changed and on 21 July pack ice was present. This small vessel tried several times to approach the island, but efforts were finally abandoned two days later when because of engine defects Emmaproceeded under canvas to the Falklands.

Shackleton now became aware the British Government had chartered Discovery from new owners to undertake a rescue mission. However, it would take at least two months to make the journey. Considering this too long, Shackleton directly approach the Chilean Navy to have Emma towed back to Punta Arenas. Admiral Muñoz authorised the naval authorities at Punta Arenas to send Yelcho.15

At Punta Arenas, Rear Admiral Luis López-Salamanca ordered First Mate Miranda, commanding Yelcho,to comply with this mission. Many delays were experienced until finally the captain declared himself sick. As a doctor could find no physical illness, the Admiral transferred Second Mate Pardo from command of the cutter Yáñez to command Yelcho.A few other less enthuastic Yelcho crewmembers also received sudden postings.

Yelcho then sailed to the Falklands on 7 August and returned to Punta Arenas seven days later with Emma in tow. This transit was not without setbacks as the towing hawser parted several times in extremely heavy weather. Emma’s difficult trip to Elephant Island with Aguirre on board and the successful towing operation performed by Yelcho under command of Pardo created a trusting relationship between Shackleton and these two Chilean officers.

Pardo acknowledged the perils involved in a letter to his father immediately before departure, saying:

Although the mission is difficult, and full of risks, I did not hesitate in accepting it due to its humanitarian character, among other reasons. These huge ice blocks provoke respect. But the work proposed to me is also big and nothing will intimidate me: I am Chilean.

I would be happy if I achieve something where others had failed. If I fail and die, you will take care of my Laura and my children because there will be with no other support than yours. If successful, it would be in compliance with my duties as a mariner and as a Chilean. That would be my glory.

Yelcho, under Pardo’s command but with Shackleton and two of his men aboard, sailed from Punta Arenas in the early hours of 25 August 1916. The small cutter used interior waters to avoid the worst of the weather and spent the first night sheltering, then proceeded through the Beagle Channel to Ushuaia, on the Argentinean coast of Tierra del Fuego, where they remained overnight. At dawn she weighed anchor to reach Picton Island, where the navy had coaling facilities. After replenishing, with a fuel reserve stowed in sacks on the upper deck, the ship was ready for the final push towards Elephant Island.

The passage, in fine conditions, provided good astronomical fixes. Next day, icebergs were sighted before entering fog. When 150 nm (178 km) from their destination, conditions grew worse and speed was reduced. On Wednesday 30 August, with the horizon again visible, speed was increased, although Yelchowas close to reefs and still sailing among icebergs. At 10:30 that day, the coast was observed and two hours later they approached Cape Wild, where Shackleton had left his men five months previously. Pardo recalled this last obstacle:

If the fog had not been an enough obstacle, the sea currents placed a big floe between the island and our ship. It not only prevented us the observation of the shoreline, but also closed completely the way towards a landing place.16

As they approached the shore, one of the shipwrecked mariners saw with astonishment the silhouette of a ship. At his call, others rushed from their precarious shelter to the welcoming sight of a ship flying Chilean colours. The survivors were first seen from the cutter at 13:30 and their calls were heard.17Soon a boat with Shackleton and one of his men and a Chilean crew member was rowing towards the refugees. The first encounter was truly emotional, as it was also when the twenty-two shipwrecked mariners arrived in Yelcho, bringing with them their most valued possessions, including scientific instruments, photographic and cinematographic materials, and precious testimony of their odyssey.

Significant images taken by the Australian photographer James Francis (Frank) Hurley, were saved. Hurley later became an official photographer of his country’s forces during both world wars.18When the Chilean training ship Esmeralda called at Sydney for the first time in 1961, Hurley visited the ship (the author of this article was a midshipman onboard). Perhaps this was the second time he had ventured aboard a Chilean navy ship. Sadly, he died the following year.

A few days later in a newspaper interview Pardo described his thoughts on having all the rescued men aboard:

It is impossible to give you an impression of the excitement of that moment; I can only tell you that this has been the most beautiful reward for the efforts that we had made in favour of the expedition members…19

These men had remained five months between autumn and winter, surviving in primitive and inhospitable conditions with scarce provisions, on a rocky foreshore in the worst of weathers. Sometimes they managed to hunt mammals and birds or they collected seaweed to improve their meals, but there were periods when weather conditions prevented them from moving from their narrow, damp and dark shelter.

Within one hour of arrival all were onboard and the return voyage started, aiming to be clear of the shore before the formation of pack ice. Visibility was again poor and the next day worsened with periods of snow. Pardo intended using the Beagle Channel to reach Punta Arenas. Fog thwarted this and they continued sailing the longer route before entering Magellan Straits on the evening of Saturday 2 September. Rough seas prevented sending a boat inshore to telegraph news of the successful rescue.

At 11:30 Monday 4 September, Yelchoanchored off Punta Arenas after nine arduous days with Pardo spending long hours on the bridge. Leon Aguirre, the second in command, said: ‘he (Pardo) only went asleep during daylight, when there was no fog and the navigation offered no danger’.20Pardo said the greatest danger was navigating among ice floes in fog conditions in non-charted waters.

The arrival of Yelcho drew crowds at the dock to greet the Shackleton expedition and their rescuers. News of the success of the fourth attempt spread through the telegraph and aroused great enthusiasm at national and international levels reflected in front pages of the major newspapers worldwide.

Then came celebrations with local families taking home the rescued men. Shackleton expressed his gratitude in a letter to the Naval Director General, and answered by Admiral Muñoz, saying that this service had received the news of the rescue as if it had been of its own members. The British explorer also expressed his feelings in a media interview, saying: ‘My admiration for your navy is largely due to the effort on saving my colleagues. I thank you on behalf of my men, myself and of England’.21

The day after arrival, Pardo delivered his official report. It stressed that the mission came to a successful conclusion thanks to the collaboration of all the ship’s company. The Base Admiral, when sending this document to the Naval Director General proposed Pardo’s promotion to First Mate. On 7 September, he was officially promoted to the higher rank. On the same date, the Director General approved the appointment of Second Mate León Aguirre to the Navy List, since his previous appointment was as a reservist.22

Shackleton wished personally to thank the national authorities. To do this, Yelcho steamed to Valparaiso with the same crew, also carrying Shackleton and most of his men. Some from the expedition had already begun their return in a merchant ship.

Dressed overall, Yelcho arrived at Valparaiso on 27 September 1916, causing one of the largest demonstrations of rejoicing by the people of this great maritime city. All naval ships in port manned their decks and cheered in salute to the gallant little ship, while all the merchant ships blew their whistles and sirens. They received a well-deserved heroes’ welcome.

They then travelled to Santiago with more tributes. Shackleton and Pardo were hosted by the Sociedad Chilena de Historia y Geografía (the National Society devoted to Historical and Geographical Research). President Juan Luis Sanfuentes-Andonaegui granted them an audience where Shackleton was able to express his gratitude. Also involved were the Foreign Minister, Juan Tocornal-Dourscher, and Minister for War and Navy, Jorge Boonen-Rivera, who authorized the rescue.

Upon leaving Chile, Shackleton with one of his officers, travelled to New Zealand. Between December 1916 and February next, they participated in the rescue of the ten men left on the shores of the Ross Sea by Aurora.23The rescue was achieved after Aurora had been refitted in New Zealand and made contact with the Ross Sea Party on 10 January 1917; by this time, three of the castaways had died from their long exposure.24

The aftermath

Memories of Pardo and his subordinates were soon forgotten, being overshadowed by Shackleton’s skilled publicity, necessary for him in raising resources for yet another Antarctic expedition. However, locally Pardo and his men continued to be honoured. Two ships have used the name of this outstanding officer; an Antarctic ship built in the Netherlands that operated between 1959 and 1997 and, an oceanic patrol boat locally built by ASMAR,25entering service in 2008. A monument to Pardo was placed at Point Wild on Elephant Island during the Antarctic expedition of 1987-1988.26Replicas of this monument are in the Chilean Antarctic bases of Arturo Prat and President Frei.

Stories published abroad do not do justice to the participation of Pardo and the Chilean Navy. Nelson Llanos says that in over one hundred and twenty articles published by the British and American press they only receive four mentions.27From such literature, it can be assumed Yelcho completed the rescue under Shackleton’s command. While Shackleton at first acknowledges the role played by Pardo, he later changed emphasis to suit his own interests. For example his book published in 1919 recognizes the participation of Chileans in the preface, but the main text presents facts in a way that can be misunderstood.28

This attitude relates to the historic period. Explorers enjoyed fame in the era of the great empires. In the British Empire, which had begun to wane, and in the United States, an emerging power, little attention was paid to peripheral countries like Chile. National luminaries such as Shackleton helped distract attention from the horrors of war and, when the conflict ended, peacetime heroes were welcomed.

Summary

Shackleton was a great explorer who failed in his attempt to cross Antarctica. His story is, however, a great lesson in leadership. Firstly, Shackleton carefully selected and led his people through extremely difficult circumstances. Then, at Elephant Island, he made a momentous decision involving taking the best boat and his five strongest companions to reach South Georgia, leaving the rest under the leadership of his deputy and unsung hero, Frank Wild.

On the Chilean side, there are also demonstrations of great leadership. Pardo as captain of Yelcho knew the risk of going to Elephant Island as he had extensive experience in southern waters with this type of vessel. Meanwhile, Second Mate Aguirre had lived through the experience of approaching the same island in Emma. Pardo was decisive; he sought volunteers to complete his ship’s company and skilfully took advantage of all environmental conditions in making the rescue.

Published material of these events does not recognize the importance of the high command of the Chilean Navy. The Director General made difficult decisions, relying on the ability of those under his command serving in the Magellan region, while the Admiral at Punta Arenas readily made changes regarding the positioning of ships and personnel.

The rescue by the Chilean Navy of Shackleton’s expedition is a milestone of great importance for this country. It was the starting point of the presence by the Republic of Chile in Antarctica. This is reinforced by the establishment of the Prat Base, the first of other Chilean Antarctic bases. Since this initial rescue countless others have been made by ships and aircraft in compliance with national tasks or derived from international obligations in safeguarding human life in these distant waters.

Notes:

1 In Chile (and many other Spanish speaking countries) the full name of a person is: first, the given name (Luis) then, father’s family name (Pardo) and last, mother´s family name (Villalón). In this article names are put in the following format: given name and father’s family name after the first entry.

2 Extracto de la Hoja de Servicios del ex piloto 1° Sr. Luis Pardo Villalón, 07 de Agosto de 1957. En: Archivo Histórico de la Armada. Luis Pardo. Summary of Personal Record, Chilean Naval Archive, Valparaíso.

3 One is: Alfonso Filippi- Parada, ‘Shackleton versus Pardo’, Revista de Marina, v. 117/858 Septiembre-Octubre 2000. Another is: Regina Claro Tocornal, ‘La Odisea de Sir Ernest Shackleton y su rescate, Proeza de la Marina Chilena’, Boletín de la Academia de Historia Naval y Marítima de Chile,N° 10 (2007), p. 103.

4 Decreto Supremo (Supreme Decree) N° 927 del 23 de mayo de 1919. Extracto de la Hoja de Servicios del ex piloto 1° Sr. Luis Pardo Villalón, 07 de agosto de 1957. Summary of Services Performed by retired First Mate Luis Pardo. In: Chilean Naval Archive, Valparaíso.

5 Endurance is described as a three-masted barquentine. See: Endurance (1912 ship) in: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endurance_(1912_ship). Access: 24 May 2016.

6 SY Aurora is described as a steam yacht. See: Aurora in: http://everything.explained.today/SY_Aurora/. Access: 23 May 2016.

7 These subjects are covered in: Ernest Shackleton. Sur. Historia de la última Expedición de Shackleton 1914-1917, (Usuhaia, Argentina: Editorial Sudpol, 2014), chapters XIII to XVII. This is a Spanish translation of the original English version published in 1919.

8 Regarding this part of the voyage, the excellent narrative of: Alfonso Filippi-Parada, Lecciones de un Rescate, (Valparaíso: Corporación Cultural Arturo Prat Chacón, 2 ed., n.d.) was followed.

9 Bar is the International System unit of pressure equivalent to 14.5 pounds per square inch.

10Carlos Tromben-Corbalán, Ingeniería Naval, una Especialidad Centenaria(Valparaíso: Dirección de Ingeniería Naval) pp. 208-210.

11Decreto supremo (Supreme Decree) N° 190 27 January 1958. In http://www.armada.cl/armada/tradicion-e-historia/unidades-historicas/y/escampavia-yelcho-1/2014-02-14/164005.html. Access: 6 NOV 2015.

12Pack Ice also known as ice pack or packis any area of sea ice(ice formed by freezing of seawater) that is not land fast; it is mobile by virtue of not being attached to the shoreline or something else’. Encyclopedia Britannica. In: http://global.britannica.com/science/pack-ice. Access: 18 May 2016.

13Filippi,Lecciones de un Rescate…, p 237.

14Biographical information in Jorge Sepúlveda-Ortiz, ‘Piloto 2° don León Ramón Aguirre Romero, Segundo Comandante de la escampavía Yelcho’, Revista Mar, N° 201 ISSN: 0047-5866,2015, pp. 91-93.

15Telegrama del Director General de la Armada al Gobernador Marítimo de Magallanes de 7 de julio de 1916. In Archivo Histórico de la Armada. Telegram message from General Director, Chilean Navy, to Punta Arenas Naval Base on 7 July, 1916. In Naval Archives, Chilean Navy, Valparaíso.

16‘El salvamento de los compañeros de Shackleton’. El Diario Ilustrado, Santiago 6 de septiembre de 1916, p. 2. Adaily newspaper published in Chile’s capital city.

17Bitácora de la escampavía Yelcho. En Archivo Histórico de la Armada. Cutter Yelcho Log Book, Chilean Naval Archives, Valparaíso.

18More about Frank Hurley’s work in: Filippi, ‘Lecciones de un Rescate….’., p. 118. See also, Kodak. Endurance, In https://www.kodak.com/US/en/corp/features/endurance.Access: 21 May 2016.

19‘El salvamento de los compañeros de Shackleton…’, El Diario Ilustrado, Santiago, 6 Septiembre 1916, p. 2.

20‘Una charla con el comandante de la Yelcho’, Revista SucesosN° 732 (5 de octubre de 1916). In Consuelo León Wöpke, Mauricio Jara Fernández (editores), El Piloto Luis Pardo Villalón, visiones desde la prensa 1915, (Valparaíso: LW Editorial, 2015), pp. 247-251.

21‘Llegada de la expedición de Sir Shackleton a Valparaíso’, Diario Ilustrado, Santiago, 14 Septiembre 1916.The arrival of Shackleton expedition as covered by El Diario Ilustrado, a Chilean newspaper.

22Oficio del Director General de la Armada al Director del Personal del 7 de Septiembre de 1916. En Archivo Histórico de la Armada, Oficios de la DGA, folio 0033. Official letter from Director General of the Navy to Director of Naval Personnel, Chilean Naval Archives, piece 0033.

23By Regina Claro, p. 103 and Shackleton, pp. 333-368. This part of this memoir covers extensively these subjects on Chapters XVI and XVII.

24Shackleton, pp. 365-368.

25ASMAR Astilleros y Maestranzas de la Armada is the Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Company created by the Chilean Navy.

26It is recognized as Historical Antarctic Monument No. 35 by the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. In http://www.ats.aq/devPH/apa/ep_protected_detail.aspx?type=1&id=5&lang=s. Access: 12 January 2016.

27Nelson Llanos Sierra, ‘Una historia distorsionada: el rescate de la Isla Elefante a través de la prensa Anglosajona, 1916’. In Consuelo León Wöpke, Mauricio Jara Fernández (editores), El Piloto Luis Pardo Villalón, visones desde la prensa 1915, (Valparaíso: LW Editorial, 2015), pp. 85-99.

28Shackleton’s original book has a translation into Spanish made in Argentina: Ernest Shackleton. Sur. Historia de la última Expedición de Shackleton 1914-1917, (Usuhaia, Argentina: Editorial Sudpol, 2014), p.17.