- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, Biographies and personal histories, Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Suva

- Publication

- December 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By John Smith

Possibly not many have heard of HMAS Suva as she had an extremely short history as a commissioned Australian warship. She did however have the distinction of wearing the flag of a full Admiral during most of this period.

Admiral Sir John Rushworth Jellicoe

Let us step back in time to the Great War. At the outbreak of war in August 1914 both the First Sea Lord (Fisher) and First Lord of the Admiralty (Churchill) demanded change and the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet was unceremoniously cast aside. John Jellicoe was promoted full admiral and assigned command of the renamed Grand Fleet and shortly afterwards received a knighthood. Admiral Jellicoe then led the world’s largest Fleet into action at the Battle of Jutland in 1916.

Jellicoe was highly intelligent and self-confident, a man of strong opinions, with an autocratic air which did not make him universally popular. A nation seeking another Nelson was disappointed in his cautious approach in this battle of Goliaths and he is perhaps unjustly criticised for allowing the German High Seas Fleet to escape. In the aftermath, Jellicoe was replaced as Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet by a more dashing Admiral, Sir David Beatty. Jellicoe was, however, promoted to First Sea Lord, but this did not last long, as after a severe disagreement with the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, over the use of convoys in the so called ‘Submarine Crisis’ he was asked to leave his office.

Jellicoe resigned in good grace and as a face-saving gesture was elevated to the peerage. He was also offered the Governor-Generalship of Australia but declined on the grounds he had insufficient financial resources to maintain the position, although his wife came from a rich family. He did however express an interest in becoming Governor-General of New Zealand, if and when this position should become available. From starting the war as a Commander-in-Chief of the world’s largest fleet of warships he finished the war unemployed.

The Empire Mission

At an Imperial War Conference which met in London in March 1917 the Dominion Prime Ministers rejected the Admiralty proposal for a single post-war Imperial Navy under central authority. Preferring they should develop their own navies but recognising the need for uniformity in construction, armament, equipment, training and administration, the Australian and Canadian Premiers took the lead in requesting that a highly qualified representative of the Admiralty make a tour of the Empire on these matters and help to draw up a scheme to enable them to effectively plan for their future naval defence. New Zealand and India supported these proposals and, as South Africa did not then have a naval service, they were not consulted. Somewhat surprisingly, given his firm opinions, it was agreed that Lord Jellicoe would be an admirable choice to lead this mission.

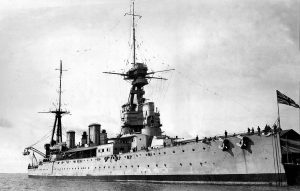

While thoughts of empire are now far removed from memory it should be recalled that at this time with gains from German and Ottoman territory the British Empire reached its zenith. With a full staff, Lord and Lady Jellicoe embarked on his mission in the battle-cruiser HMS New Zealand, departing from Portsmouth on 21 February 1919. During the course of this mission, which was initially seen as both diplomatically and potically successful, he received the prestigious accolade of being created an Admiral of the Fleet. New Zealandsailed via Suez for India, Ceylon, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States before returning via Panama and the West Indies, reaching Portsmouth in late January 1920. The overall voyage around the world and the British Empire took a little under one year.

New Zealand’s first Australian landfall was at Albany which she reached on 15 May 1919. They were met by Rear Admiral Creswell and Captain G. F. Hyde, RAN, the captain being know to Jellicoe who had requested he join his suite. Here the Admiral and suite disembarked and proceeded overland before rejoining the flagship for passage to Port Lincoln, Adelaide, Melbourne , Hobart and Jervis Bay (to visit the Naval College) reaching Sydney on 23 June. In Sydney she was to again meet her sister-ship HMAS Australia.In early August New Zealand was briefly dry-docked at Cockatoo Island.

An interesting summary of daily proceeding taken from the log of the battle-cruiser for 30 June 1919 reads:

New Zealand dressed ship and fired a 101 gun salute on signing of Peace Terms by Germany.

Held Thanksgiving Service with Their Excellencies the Governor-General & Lady Munro-Ferguson and State Governor & Lady Davidson attending.

Address by His Excellency the Governor-General.

Manned and Cheered Ship and Spliced the Mainbrace.

Illuminated Ship, Searchlight Display and Firework Display.

With the Admiral and staff absent in July, New Zealand spent a considerable time exercising out of Jervis Bay; during this period 120 Cadets from the Naval College visited the ship.

HMAS Suva

With the Empire Mission’s visit to Australia it was also planned to visit some northern Australian ports and those of nearby Pacific islands. It had been decided beforehand that it would be unwise to take such a large ship as New Zealand inside the still largely uncharted waters of the Barrier Reef. The RAN having nothing suitable to accommodate the Admiral and 16 staff plus ladies, a smaller vessel was accordingly pressed into service as a de-facto Admiralty yacht.

The 2,229 ton steamer Suva had been built in Belfast in 1906 for the Pacific island trade of the Australasian United Steam Navigation Company. In July 1915 she was requisitioned by the Royal Navy as an armed patrol vessel and was used in the Red Sea. She played a significant role in supporting T. E. Lawrence’s (Lawrence of Arabia) Arab Revolt when she bombarded several Turkish garrison towns and with her naval landing parties helped secure three towns.

At the end of the war she returned to Sydney but for some time remained under naval control. After refitting at Garden Island, with her main armament removed and replaced by two 3 pounder saluting guns, she was commissioned into the RAN on 24 June 1919. The new HMAS Suva was under the command of Captain G. F. Hyde, RAN1and only 50 days later paid off, on 12 August 1919. Shortly afterwards was returned to her owners. And so ended possibly the shortest history of a commissioned ship in the RAN. Suvawas sold to Philippines interests in 1928 and was sunk following Japanese bombing of Manila on 16 April 1942.

Suva had a crew of 11 officers and 50 men; owing to her merchant origins many of the engine room crew were supplied by her previous owners under short-term RANR contracts. An addition to her complement was Rear Admiral E. P. F. Grant, RN who had recently arrived from England to relieve Rear Admiral Creswell as First Naval Member of the Commonwealth Naval Board. Rear Admiral Grant was accompanied by his Secretary Paymaster LTCDR Eyre S. Duggan, RN and another passenger was Captain the Hon. B. Clifford, Private Secretary to the Governor-General.

The long serving public servant and one-time Assistant Secretary of the Department of Defence, Robert Hyslop2, makes the following comments regarding Jellicoe’s time in Suva.

The indiscipline after 1918 and also the fact that some British officers identified with the Australian navy are illustrated in the sorry (and exceptional) story of the commissioning of a merchant ship HMAS Suva by Captain G. F. Hyde, RAN, in 1919 to take Admiral of the Fleet, Viscount Jellicoe, on a cruise of the Pacific Islands. Hyde had reported that ‘speaking generally the conduct of the very large proportion of the ship’s company was that of a dirty, untrained and ill-disciplined mob’. Jellicoe had said, ‘I could not fail to be struck with the untrained and ill-disciplined crew of HMAS Suva ….. there are of course exceptions amongst the ship’s company but taken as a whole I regret to state that I am in agreement with the remarks of Captain Hyde’.

On 28 June 1919, after partaking of afternoon tea in the flagship, officers, staff and retinue from the Empire Mission transferred to Suva. At 0900 the following morning the flag of the Admiral was broken in Suva and struck in New Zealand. At 0930 Suva sailed for Brisbane, but without her admiral as Lord and Lady Jellicoe had arranged to go there by train. At 1630 on 5 July Suvaslipped and proceeded via Cairns to Port Purvis in the Solomon Islands. This was the start of her cruise to the northern Australian ports, Solomon Islands, New Britain and New Guinea.

Though relatively small, Suva was quite comfortable. To ensure that there was adequate office accommodation, the saloon and three deck cabins and a further three cabins below had been fitted out as offices, with the staff being divided amongst them. The respite from interruptions caused by festivities and entertainment was very welcome but the work pressed forward unremittingly as the various ports visited hitherto were analysed and considered by the Admiral, as well as the larger questions dealing with the Pacific generally.

The weather conditions at first were rather worse than expected with the benefit of the South East Trade and for two days the ship rolled heavily over about 30 degrees either side. At times her speed fell from about 10 knots to 8 knots; this was largely attributed to the inferiority of the New South Wales (Bulli) coal she carried. Later on, due to poor steaming qualities of this coal, a certain amount of the original programme had to be curtailed.

Admiralty charts show Port Purvis lying about 12 km south east of the township of Tulagi on the island of Tulagi, which until 1942 was capital of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate. The visit commenced in embarrassed silence as on arrival the Resident Colonial Administrator was unable to find the ship owing to the anchorage being unknown locally by this name. The Admiral and staff embarked in a motor launch looking for some habitation and surprised a mission settlement before eventually meeting the Administrator.

Visits were also made to Florida Island in the Solomons and Rabaul in New Britain where they were met and were saluted by another yacht-like companion, HMAS Una. For a while the Admiral’s flag was transferred to Una while he made a visit to the Duke of York Islands. Thence homeward via: Samarai, Port Moresby and Thursday Island. Several overnight anchorages were made inside the reef before reaching Gladstone. From here the Admiral and staff departed by special train calling at Newcastle, where they inspected military facilities and investigated the potential of Port Stephens, before reaching Sydney. From Gladstone Suvaproceeded independently to Sydney. From 06 to 08 August New Zealand was briefly dry docked at Cockatoo Island So it was not until 08 August 1919 the Admiral and his staff returned to New Zealand when his flag was transferred from Suva to the battle-cruiser. Lord and Lady Jellicoe with their staff departed from Sydney in New Zealand bound for her namesake land on Saturday 16 August 1919.

The Jellicoe Report

In preparing his Australian report Jellicoe was not starting with a blank piece of paper, having the advantage of an earlier report commissioned by the fledgling Commonwealth Naval Force. This report, prepared by Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson in 1910, formed the basis for the establishment of ships and establishments necessary to sustain an Australian Fleet.

Before departure from Australia the ‘Report of Admiral of the Fleet Viscount Jellicoe of Scapa on a Naval Mission to the Commonwealth of Australia’ was personally presented to His Excellency Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson, Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief, Commonwealth of Australia on 13 August 1919; a copy was also received by the Prime Minister. With the Australian First Naval Member and the Secretary to the Governor-General onboard Suvait can be assumed any potential difficulties in the report’s findings had been ironed out well before its release. The Report was very thorough, outlining a proposed, if ambitious, composition of a future Australian fleet together with its administration and training requirements and estimating the anticipated costs.

It supported many of the previous Henderson recommendations such as the development of a new fleet base at Cockburn Sound in Western Australia, another at Port Bynoe near Darwin and called for the Sydney Fleet Base to be relocated to Port Stephens. Somewhat progressively the Admiral was not wedded to graving docks, considering these could be replaced by floating docks. With uncanny accuracy the Report highlighted the potential threat in the Asia-Pacific region from a militarised Japan. Jellicoe, in common with many other senior Royal Naval officers, had difficulty appreciating local values of eglitarianism which he saw as leading to a critical lack of discipline within the Australian naval service.

His work completed, Admiral Lord Jellicoe, soon to be Admiral of the Fleet, sailed from Sydney in New Zealand on 16 August and arrived in Wellington four days later. After returning to England the grand old sailor received his wish and from 1920 to 1924 served as a dedicated Governor-General of New Zealand. Lord Jellicoe died at his London home on 20 November 1935, just short of his 76th birthday.

In a post-war environment where the world sought peace and reduced expenditure on armaments, implementation of the Report’s recommendations, although well received, was politically unacceptable. However, in general terms it became the basis for future planning of the RAN. It is perhaps quite remarkable that the future of the RAN was largely shaped, planned and decided by staff working diligently for a few weeks in the island trader and part-time warship Suva.

Notes:

- Captain George Francis Hyde was to have his own distinguished naval career, as Admiral Sir Francis Hyde, he became the first RAN officer to achieve this rank. The Admiral’s term as First Naval Member had been extended from five to six years but just before his intended retirement he developed bronchial pneumonia and died prematurely on 28 July 1937, a week after his 60th birthday.

- Quoted from Robert Hyslop’s book Australian Naval Administration 1900-1939, published by Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, 1973.