By Ross Gillett

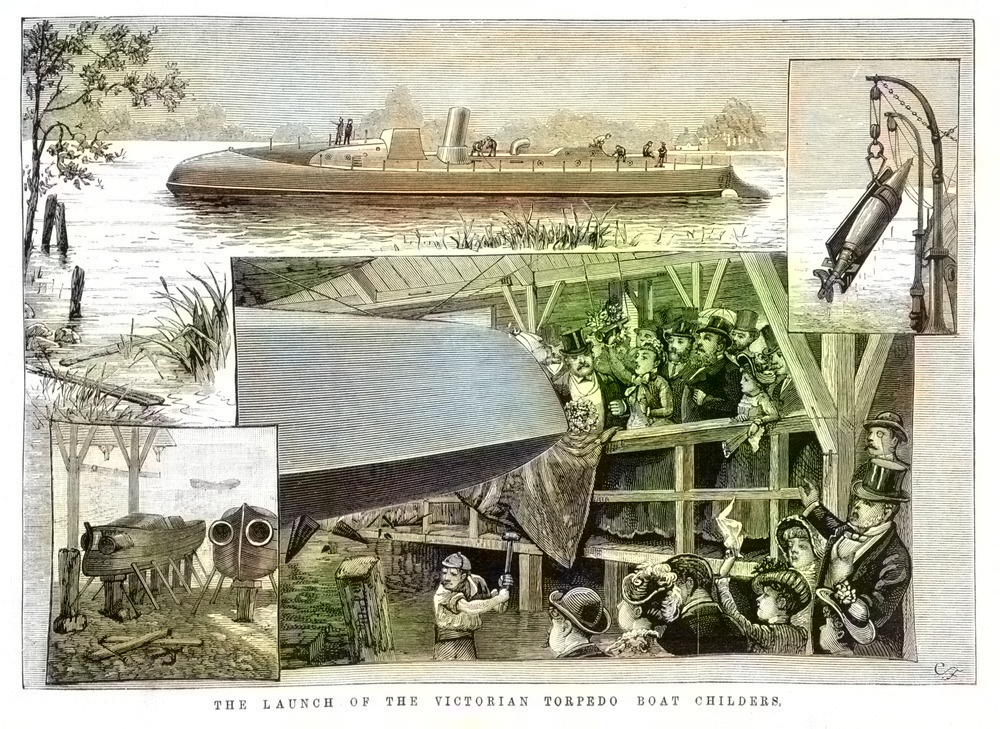

When the Victorian Government’s first-class torpedo boat HMVS Childers had moved safely out of Portsmouth on 3 February 1884, the 26-year-old commander, Lieutenant Martyn Jerram, went down to his tiny wardroom and wrote in his journal: “0700 cast off from jetty and commenced our long voyage, only a few early boatmen giving us a final cheer as we passed out, the Duke and the Excellent not even acknowledging our farewell dip of the colours.” This wistful note is understandable.

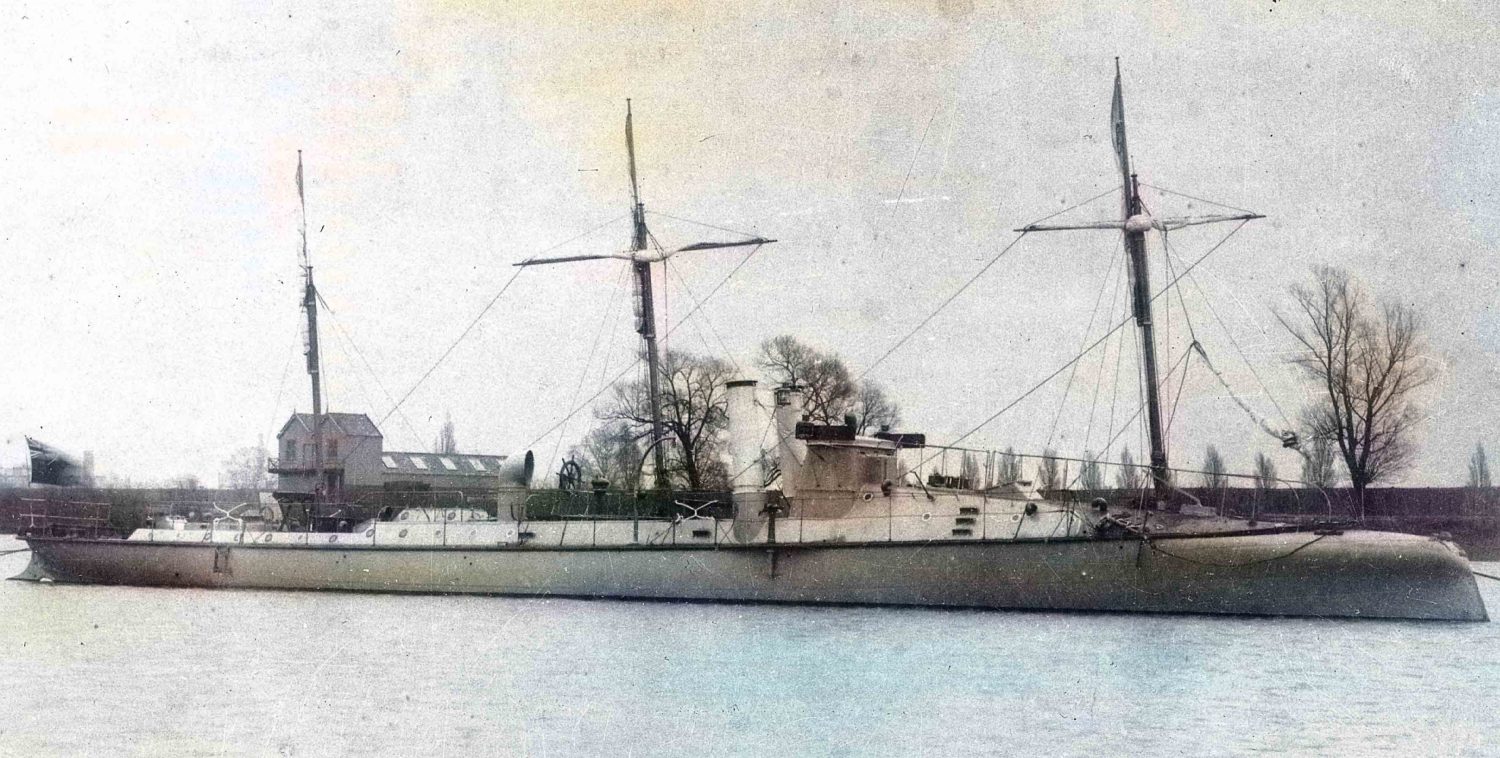

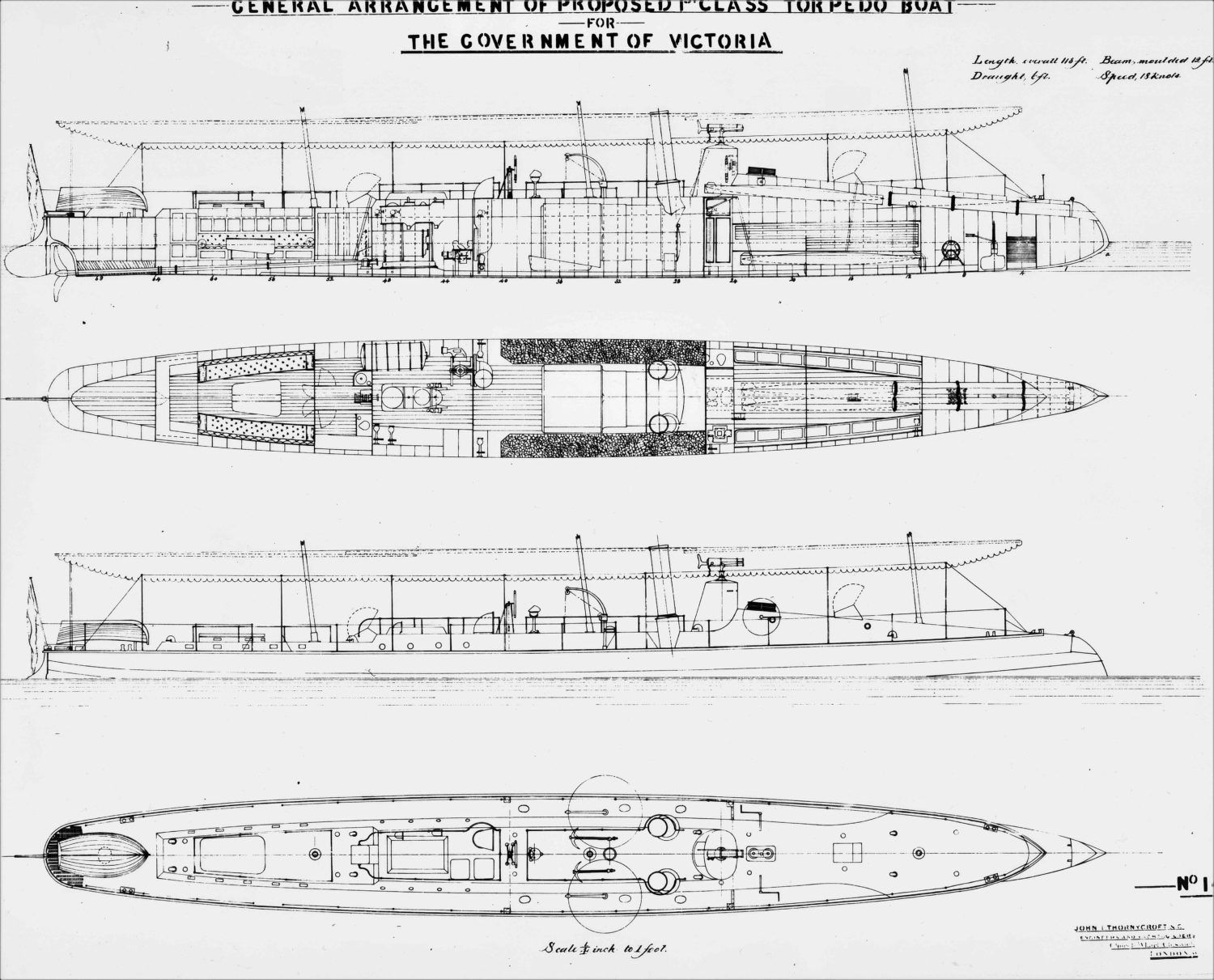

To Jerram and his men the voyage to Australia in their new lightweight warship must have seemed in the nature of a voyage into the unknown, deserving of a send-off, at least. She was only the second of her kind. A sister, sold to the Russians, had distinguished herself. But would Childers survive the heavy, open seas? Would the coal last on the long stretches? Her beam was only 12-ft. 6-in. Her draft, forward was only 2-ft. 6-in. She would be a very wet ship!

First stretch

On the voyage down from Chiswick, where she was built, she had bucked about at anything over seven-knots, everyone had been seasick, and the pilot had remarked that when she lifted her stern, she “rang like a bell.”

Jerram wrote at the time: I found out how tender she is. The mark of a cork fender was actually left in her side bulging in the plates and leaving a distinct impression. The apparatus for feathering the screw was a bit primitive. I don’t like it at all. It will never be a success if there is any sea, or on a dark night. There had been difficulty, too, in getting trained crew. One young man in the decorating line, answering an advertisement for engine room artificers, had wanted to know whether any previous knowledge was necessary.

Jerram commented acidly in his journal: there were various others manifestly unfit, but in their own opinion quite competent to keep engine room watches.

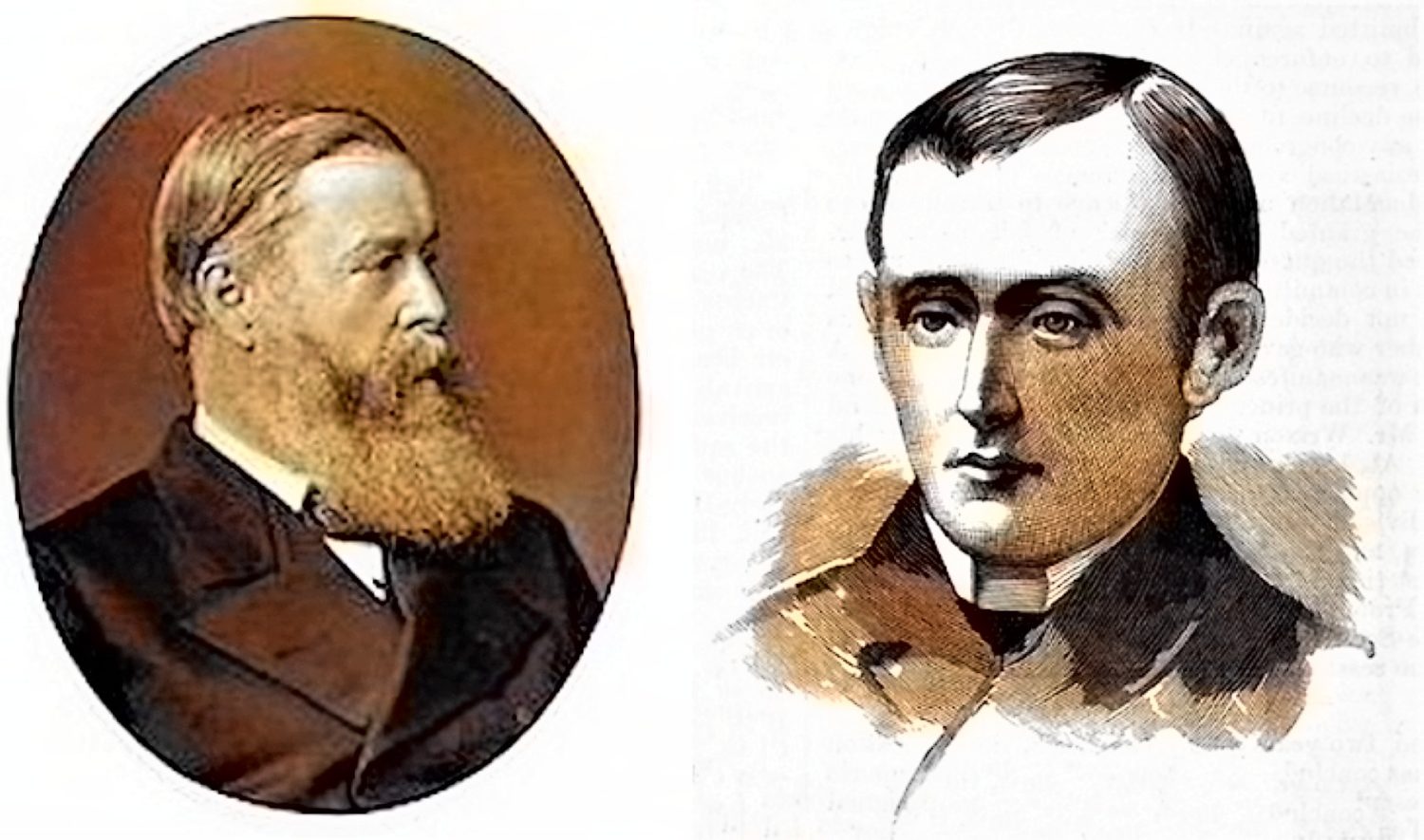

Perhaps, in addition, the lieutenant’s conscience was troubling him, for the day before a portrait of Mr Childers, Chancellor of the Exchequer (he was formerly a member of the Victorian State Parliament) had arrived, with instructions to hang it in the mess. It’s too big the entry in the journal commented (with ‘big’ underlined) so he did not unpack it.

Towards Spain

With her bunkers full, the boat plodded on to Gibraltar, the coal supplies, considered sufficient for this first leg of the voyage. Their modest fears fell away, and they began the run down the Bay of Biscay to Spain. The glass was steady and high, and, in spite of a beastly cross swell, which turned nearly everybody up, Childers kept up a steady 10-knots.

At the port of Vigo in north-western Spain, where the crew took on eight-tons of coal (100-miles a ton at economical speed), there was a small difficulty about status, for Childers, with her slim hulk, seemingly outside masts and the airguns in her bows to discharge the torpedoes, presented an unusual sight.

Jerram noted, with an almost imperceptible turn of humour that often sweetens, an entry in the closely written pages that the Captain of the port inclined to be obstructive. However, eventually the boat was passed off as a man-of-war.

On 10 February, out of Cadiz, coal trouble began, and Childers had her first taste of one of the high indignities of the sea – being towed:

At 0200, I was informed that there was about two and (the fraction is illegible) tons of good of coal left, ample at any rate to take us to Cadiz and sufficient to take us to Gibraltar. In the forenoon, it was reported that there was less, than had been calculated, but sufficient to reach Cadiz. I therefore altered course for Cadiz, but almost immediately I was informed that we had only coal for 10-miles. Cadiz was then 50-miles off.

S.S. Pathan came to her rescue and towed the torpedo boat into Gibraltar. The bill to the Victorian Government was £180.

Mediterranean Sea

Malta was reached, with only four buckets of coal in hand, a fortnight after leaving Portsmouth. Here, Childers was joined by the two schooner-rigged gunboats, HMV Ships Victoria and Albert, displacing 530 and 350-tons, respectively. Both had also been built for the Victorian Government and were to accompany Childers to Melbourne. The three newcomers would swell the Victorian naval force to five ships, the other two being Cerberus, an iron-plated turret ship, and Nelson, an old wooden warship dating back to 1814.

Here, with great relief, the feathering screw was removed and a new one, brought by the gunboat Victoria, was fitted. During this port visit Captain Thomas from Victoria purchased musical instruments for the crew to relieve their boredom. Also, orders were received, with some excitement, to join Admiral Sir William Hewett’s squadron at Suakin, Red Sea port of the Sudan, where Osman Digna, the slave dealer, was fighting with the Mahdi against British troops and marines.

The three vessels sailed on 8 March, with the new screw seeming to have made a difference, with Childers making 500-nautical miles in 48-hours, surprising the local Turks by the speed the boat came up Suda Bay.

Sudan

At Port Said, however, the little boat suffered another of the sea’s unbecoming experiences. She went aground, due to the “quartermaster being drunk.” Next day it happened again. This time no explanation was given, except that it was “unfortunate”.

She entered Suakin roads with her airguns bristling and Lieutenant Jerram on a special seat rigged to the mast to get a better view, but the fighting there was over . . . “it was very provoking.”

Then followed an entry which points up much more than quaint descriptions of old-fashioned ships can do. That is, what has happened in the world since Childers missed out on the Sudan campaign.

In the afternoons I generally went ashore, walked about the camp, &c., trying to pick up spears, &c., and am very glad we came in as war is certainly worth seeing even on this limited scale.

On the way to Aden, Childers gave an alarming demonstration of how she could roll like a pig. In a steep head sea, she took water everywhere, even down the funnel. Towed by Victoria, she behaved as if she were about to leave, yawing all over the place, ducking beneath the waves, and the towrope parted.

Some of the crew had a week in hospital at Aden. Lieutenant Jerram was laid up aboard Albert for three days with salt-blistered feet. Departing on 31 March, again in tow, the torpedo boat moved steadily on smooth waters across the Indian Ocean. Two other officers, Williams and Stewart, were learning the semaphore and all had learned the Morse alphabet and played numerous Rubbers of the dummy whist card game.

Ceylon

The vessels left Aden on 31 March. The larger of the two gunboats, Victoria, began towing Childers to save the boat’s coal supply, with Colombo reached on 13 April. There they cleaned up the boat. Jerram noticed a Russian transport for Vladivostok with 500-convicts aboard and went to Kandy for 36 hours – “glorious scenery going up and down but not much to see there.”

Between 20 April and 3 May Childers and the gunboats were moored in Batavia. The torpedo boat needed to steam under her own power again on 13 May after the tow line to Victoria parted. The following day another line was attached but also parted on 16 May.

Down the picturesque coast of Sumatra, through seas of pumice thrown up by Krakatoa the year before, and Childers was in the Arafura Sea and on the verge of the worst experience of the voyage.

May 13, 1884, … all serene, when a heavy rain squall came up and we had a regular dog’s life for the next five days. The boat knocking about like a cockleshell, water, water everywhere, on deck, through the hatches, through the bottom; wet all through the time. Twice the tow-line broke. They had to ‘parcel’ the hawser, which was chafing against the hinges of one of the airguns – very easy to talk about, but difficult to do.

Jerram held on to Williams, Williams held on to a bowline around A.B. Norman, and Norman held on to an old coal bag and a palm and needle, with which he finally stopped the chafing. They all were nearly washed overboard … I never spent such an awful time in all my life. Captain A. B. Thomas, who was in charge of the convoy, later described the condition of Childers….At one moment a glistening prow would be seen emerging from the body of an immense wave at an angle of some 45-deg., while at another a quivering stern with a wildly whirling screw would appear jutting into mid-air.

At Thursday Island, Childers recovered, Jerram played cricket, watched the pearl divers (they were earning £50 a month), and had dinner at the resident magistrate’s on the Queen’s birthday.

The hotel keeper clears £2000 a year. Nothing can be got except tinned grub and live sheep, and sometimes coal. No water. All houses wood. Two hotels, one big store – Burns, Philp and Co. – a few shanties.

The next port of call was Townsville, with its shop fronts food, meat at 4d.-lb., vegetables and liquor dear … but very Sabbatarian, population mainly from Germany and China and heaps of bluejackets, deserters from the Royal Navy.

Down the east coast

The flotilla visited Thursday Island between 18-25 May, then Townsville 31 May to 2 June, Brisbane between 7-9 June and Sydney, arrving at 2300 on 13 June. In Port Jackson, Childers anchored in Farm Cove and painted herself for the later Melbourne arrival. Martyn Jerram and his crew created an excited wave of popular interest that must have sent their minds back to the lonely departure at Portsmouth. The hazards of their voyage were described in the local newspapers, in columns of praise of the gallant torpedo boat, and special reporters from Melbourne sent despatches to their offices, giving details of the fortitude and lethal powers of the Victorian Navy’s latest acquisition. The Governor and the Premier came on board and sightseeing tours were conducted.

A small crowd gathered on the Domain foreshores to farewell the vessels on 21 June. Many onlookers would have been perplexed to see Childers issuing forth masses of black smoke as she readied herself for the voyage down the coast. A witness at the scene commented that Childers seemed very eager to begin sailing and the harbour was buzzing with excitement. For locals the stopover provided a brief glimpse of these naval vessels.

Port Phillip

Sailing along the New South Wales and Victorian coasts, the trio headed for the southern colony (Childers again under tow by Victoria), arriving on the morning of 25 June. Harsh weather was waiting off Cape Schanck, at the southern tip of the Mornington Peninsula, but Childers, kicking and bucking with final determination, came through it and entered the Heads at 0900 on the 25th, 20 weeks and four days after leaving England.

Rough seas made it impossible for the crew members to play their instruments on deck as they had planned for the last part of their journey up the bay to the Williamstown depot. Childers‘ voyage from England spanned 13,323 nautical miles. A total of 121 days were spent with Albert and Victoria.

The captain then made one of the last entries in his journal:

Now the cruise is really over (‘over’ underlined twice). I need hardly say very much to my relief; and perhaps I may add that I feel not only glad it’s over but rather proud of having done it.

One of the crew went on record in a newspaper with a more vivid impression of the voyage:

We were under water all the way; you takes a dive at Portsmouth and you comes up at Gibraltar; you takes another at Gibraltar and you comes up at Malta; and that’s how we got here.

There are two footnotes to the story of Childers, additions that Lieutenant Jerram could not mention in his journal. When he saw the monitor Cerberus halfway up Port Phillip Bay he noted, almost in awe:

… with all the members of Parliament on board. Inter changed cheers.

However, all members of Parliament were not on board. Newspapers carried the story next day, with undisguised glee, that most of the gentlemen had been deterred from making the trip because of the weather. The second footnote is a statement made later by a member of the Gladstone Cabinet to support the view that the torpedo boat should be used only for defence:

One of those boats went the other day to Australia, under the command of an enterprising lieutenant of the navy, and the description he gave of the voyage of the boat … was such as to convince anyone who read it that it would be impossible to expect that boats of that class could accompany a fleet to sea.

Postscript

Despite the above opinion, the first-class torpedo vessel Childers would serve the colony and then Australia, for a total of 32 years, including duties during the Great War, until being decommissioned at 1630hrs on 15 September 1916. Her hull was beached ashore on Swan Island in Port Phillip. The remains of the boat now lie in water, several hundred metres off the north-east side of the island.