- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Mary Mennis

For thee we fight, dear Britain, risk our all,

That Freedom’s flag may wave upon the breeze;

Count losses gain if by them we but keep

Our Empire’s ensign greatest on the seas! –

Angus Worthington

World War reaches New Guinea

Spurred on by the desire to come to grips with the formidable German East Asiatic Squadron and ensure German possession in the Pacific did not fall into undesirable hands, Australian forces arrived in New Guinea soon after war was declared between Britain and Germany. The Australian Naval & Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) landed at Neu-Pommern (New Britain) and quickly established that German naval forces had eluded them, but after a brief skirmish took possession of the former German colony.

The Protectorate of Deutsch Neu Guinea (German New Guinea) was divided into two administrative divisions: the ‘Old Protectorate’ comprised all of German New Guinea and part of the Solomon Islands. The other division comprised the scattered island territories mainly lying north of the Equator.

Only a few Europeans were to be found in administrative and commercial centres throughout this large area. It was therefore necessary for the AN&MEF to land troops to formally claim possession.

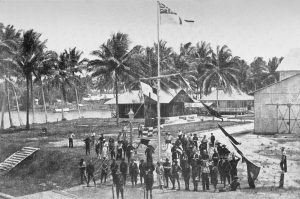

Raising the Flag

In the first instance Signal Boatswain William Hunter, who was involved in the Battle of Bita Paka, carried with him a Union Flag which was raised at Herbertshohe (Kokopo) on 11 September 1914. A piece of this flag can be found at the Australian War Memorial. A formal proclamation was made with due ceremony at Herbertshohe on 13 September when the Union Flag was again raised on a pristine flagstaff in front of all available troops including a newly-enrolled native police force. The band from HMAS Australiaplayed and a twenty-one gun salute was fired from the assembled warships.

Included in the gathering of notables was Royal Marine Lieutenant-General Edward Wylde. The General, together with his wife, had been on a private visit to Rabaul, staying with their daughter, who was married to Captain Moller, in command of the Government vessel Komet (to become HMAS Una). Prior to the AN&MEF landing the General was arrested, possibly making him the highest ranking British officer taken prisoner during WWI; he was later placed on parole and soon rescued by the Australians.

Part of a Tok Pisin (Pidgin) version of the proclamation reads:

Now you look him feller new flag, you savvy him?

He belonga British, he more better flag than other feller.

NO MORE’UM KAISER

GOD SAVE ‘UM KING

A German Imperial ensign captured at this time was hauled down by Lieutenant Basil Holmes, the ADC and son of Colonel William Homes; this is now held at the HMAS Cerberus Museum in Victoria.

To avoid capture the German Governor Dr. Eduard Haber had temporarily moved his headquarters to an inland plantation at Toma; here he managed to delay a formal surrender for several days. Following a bombardment of the ridge above the settlement by HMAS Encounter’6-inch guns, four companies of infantry with a 12-pounder gun and a machine-gun crew were sent to encourage the surrender. Terms were agreed on 17 September but did not come into effect until 21 September.

Following the successful landing on New Britain the commander of the AN&MEF, Colonel Holmes, took a garrison force of half a company of naval reservists and one and a half companies of infantry (about 200 men) to the New Guinea mainland in HMAS

Berrima, escorted by HMA Ships Australia (Vice Admiral Patey)and Encounterand FNS Montcalm flying the flag of Rear Admiral Albert Huguet. They reached Friedrich Wilhemshafen (Madang) on 24 September 1914 and with surrender terms agreed Berrima and Encounterentered harbour with the remaining ships lying off-shore. Admiral Patey, who was infuriated at the protracted nature of the surrender at Kokopo, sent a boat inshore with a simple message ‘Surrender or we will blow you to smithereens’ – this had the desired effect. A few hours later an AN&MEF contingent marched through the town and the German flag in front of the Administration Building was lowered and, it is assumed at Patey’s behest, a White Ensign hoisted signifying British rule.

Formal possession of the outer islands took considerable time. On 17th October an armed party of 15 men under the command of Major Keith Heritage in the recently captured ship Nusa arrived at Kavieng in Neumecklenburg (New Ireland) claiming British sovereignty and raised the Union Flag.

Major Heritage next took command of an expedition which left Rabaul on 19 November in the prize steamer Siar bound for the Admiralty Islands. As they neared the township of Lorengau armed Germans and native police were observed retreating inland. A belt was fired over their heads from Siar’s machine-gun and the enemy surrendered. This was the last occasion during the campaign that shots were fired. A garrison of SBLT Hext, RANR and 12 naval ratings was posted ashore and the British flag hoisted.

The remote phosphate rich island of Nauru which lies only 25 miles south of the Equator had been captured by HMAS Melbourne on 9 September and its radio station destroyed. After Melbournedeparted the island remained under de facto German rule and in an act of defiance a British Red Ensign was publicly burned. On 7 November a garrison of half a company of infantry was landed and the German flag was hauled down and replaced by the British ensign.

On 7 December a force of two companies of infantry and a machine-gun section under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Watson was despatched from Rabaul in the steamer Meklongto occupy Kieta on Bougainville Island. They landed two days later when the German colours were hauled down and replaced by the British flag. A garrison of half a company was left behind.

One Man’s Stand

The occupation of German New Guinea was successfully carried out with minimum bloodshed. All Germans and their native followers surrendered except for one Robin Hood like character, Hermann Detzner, who tormented Australian troops attempting to capture him and in the end they gave up the chase.

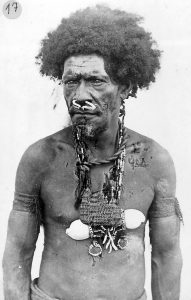

Otto Dempwolff

The final German settlement to be occupied was at Morobe, near present day Lae and close to the border with British New Guinea. This did not occur until it was visited by HMAS Yarra on 8 January 1915. Hermann Detzner was a lands surveyor based here and had surveyed much of the border between British and German New Guinea. Detzner was also a Lieutenant in the local militia. At the outbreak of war he was leading an expedition to remote parts of the territory accompanied by an armed troop of native police. In late October he received a note delivered by a despatch runner from Morobe telling him of the war and inviting him to surrender together with his men. The tone of the note affronted Detzner’s sense of Imperial dignity; accordingly he continued carrying his country’s flag into far distant parts of the territory until after the armistice in 1918 when he formally surrendered. A book of his escapades became a best seller in Germany but was not translated into English until 2011.

Pre-War Uprising

In 1904 there was a revolt by native people in Friedrich Wilhemshafen (Madang) against colonial rule. Forced labour, as a form of taxation, was used in reclaiming the marshy foreshore for future town development and road works – this was hard and tiresome work. Plantations were spreading and taking away native land. But possibly the major cause of unrest was the introduction of colonial currency which broke the centuries old monopoly, especially enjoyed by the Siar, Yabob and Bilbil people who traded clay pots along the coast in exchange for food and other materials.

The warlord of Siar Island was Maszeng and he organised a meeting of the headmen of Siar, Kranket, Yabob and Bilbil held in the men’s house on Bilbil Island. They planned to attack the German garrison on the next occasion when a supply ship was due. They knew this to be a time of celebration with much drinking when the garrison would be off-guard. The assailants planned to sail their canoes into harbour taking vegetables to market but underneath weapons would be hidden. After killing the guards they intended to raid the armoury for guns and ammunition and then rid themselves of the colonialists.

However a Biliau villager informed a missionary and the plot was thwarted. On the fateful day German troops fired over the approaching canoes, killing one man, and taking the ringleaders prisoner.

The Siar and Kranket people bore the brunt of the German anger when they realised how close they had been to annihilation. Six men from Siar and Kranket were arrested and on 17 August 1904 they were blindfolded and lined up against the stone pig fence on Siar Island and shot with the villagers forced to watch.

However Maszeng, the warlord, escaped to the mainland and hid. The Germans arrested his son Amangzen and gaoled him at Madang. Word was sent out by the local police, that should Maszeng surrender, Amangzen would be released. To save his son, Maszeng surrendered and together with his son-in-law, Kinang, they were taken to the gaol. All three men were kept in custody but the son was not released.

On 17 September 1904, the three prisoners were taken to the spot where the Madang Coastwatchers Memorial Lighthouse now stands. Three posts had been hammered into the ground and the men were tied to each of them, where they were blindfolded and shot. The Siar village people turned their backs, as they could not bear to watch. The three men were buried nearby. After this the Siar villagers were banished to the Rai Coast, where they stayed with their friends at Mindiri Village until about 1907 when they were allowed back home. However in 1912, after more unrest the Siar people were once again banished to the Rai Coast. Two years later in 1914, they decided to return to their island even if it meant defying the German officials.

A gift from Vice Admiral Patey

The Siar people had bought a western style boat named Kapok from German missionaries and some of them were returning home on this, with others in canoes. When lookouts from Australia first saw Kapok she was apprehended as it was assumed she was manned by Germans. It was therefore a surprise to find a totally local crew. The Siar were just as surprised to find Australians as to them all warships were German. The locals told their sorrowful tale which was relayed to Admiral Patey. As a gesture of goodwill the Admiral gave their chief Walok a flag. According to their oral traditions the Admiral said: ‘Take this flag back to Siar with you as a protection. From now on no-one can tell you to leave your island.’ The date that Walok received this flag was probably on the morning of 24 September 1914 when Admiral Patey in Australia was approaching the then German held town of Madang.

This flag was greatly esteemed and displayed in their local church until lost, possibly burned in 1942 following Japanese bombing and invasion, when yet another World War reached this remote locality. Many years later a school teacher knowing of the history and importance of the flag wrote to the Queen at Buckingham Palace seeking help with a replacement. This request was not forgotten.

A gift from Prince Phillip and others

In 1971 His Royal Highness Prince Phillip made an official visit to PNG in the Royal Yacht Britannia, escorted by the patrol boats HMA Ships Aitape and Samarai. The Prince took a launch to Siar Island and presented the descendants of the islanders with a Royal Naval White Ensign as a replacement flag. There was a great feast and rejoicing but the hosts were too polite to tell His Highness that this flag was not the same as the original which did not bear the emblem of the Union in the upper canton. Although now much faded this flag remains a proud trophy in the church to this day.

The author recently visited Madang and on Anzac Day 2015 attended the Centennial Dawn Service held at the Coastwatchers Memorial Lighthouse. The following day she visited Siar village and during the Lutheran Church service presented two flags. One was a Royal Navy White Ensign similar to the one the Duke of Edinburgh gave them.

The other ensign, the Flag of St George (similar to an Admiral’s Flag), was presented to Pastor Leo, the great-grandson of Walok who had been given the original flag by Admiral Patey in 1914. She mentioned the centenary of Anzac Day and told the congregation that they had their own centenary to celebrate as it is now just over a hundred years since Walok had received that flag. The local congregation, who have a strong sense of their history, erupted with cheers and clapping.

The query was then posed to the Naval Historical Society – what flag had Admiral Patey given his new found friends? This could possibly be explained by a coincidence in the timing of the original gift. Only days before, Patey had been promoted Vice Admiral and would have broken out his new flag. The Admiral may well have given his personal standard to the Siar people or a now surplus flag, signifying his previous rank. In either case this would be more in keeping with the type of flag described through local oral tradition.

In little more than a century the flags of Britain and Germany, followed by Australia and now an independent Papua New Guinea have flown over this remarkable land. Perhaps the last word belongs to Hermann Detzner who introduces the story of his travails with the following words ‘Be Proud: I Carry the Flag’.

Bibliography

Detzner, Hermann, Four Years Among Cannibals in New Guinea, Berlin: August Scherl, 1921 – English translation by Gisela Batt, Pacific Press, Gold Coast, 2011.

Mackenzie, S.S., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914 – 18, Vol. X, The Australians at Rabaul, Sydney: Angus & Robertson Ltd, Eleventh Edition, 1942.

Mennis, Mary R., A Potted History of Madang, Aspley, Qld: Lalong Enterprises, 2007.

Munday, Toni. <http//www.australian-naval-military-expeditionary-force-the-battle-of-bita-paka-a-different-perspective-toni-munday.pdf-adobe-reader> accessed 31 May 2015.

Pfennigwerth, Ian, Under New Management – The Royal Australian Navy and the Removal of Germany from the Pacific, 1914-15, West Geelong, Victoria: Echo Books, 2014.

Worthington, Angus, Our Island Captures, Adelaide: Hassell & Son, 1919.