- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Ship histories and stories, History - pre-Federation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2018 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

In an article covering Part 1 of the Australian-Indian Relationship (NHR September 2017) mention is made of the ship Sydney Cove. While she was wrecked on her maiden voyage she had such an important impact on our early maritime history that this small tribute has been prepared. The history of the ship has been particularly well documented, mainly from written records maintained by her principal officers.

The ship Begum Shaw at about 300 tons was an average sized ocean going merchantman of her day, built in Calcutta for the rice trade between India and the Persian Gulf. This was a recognised trade pattern with ships often sailing in company for mutual protection; they did not greatly deviate from known shipping routes and would be unlikely to dip south of the equator. Early in 1796 she was purchased from her owner Captain Guy Hamilton by the Anglo-Indian trading company of Campbell & Clark and fitted out for an arduous voyage, of more than twice her usual length and into the storms of the Southern Ocean, to the new penal settlement in New South Wales. In honour of the new enterprise her name was changed to Sydney Cove.

The ship was loaded with a speculative cargo which comprised 7,000 gallons (31,500 litres) of alcohol, mostly rum, sacks of rice and sugar, tea, tobacco, salted meat, Chinese ceramics, barrels of tar, casks of vinegar, footwear, soap, candles and textiles. Some unusual items in the cargo were a musical organ and a horse-drawn buggy. There was also some livestock with a few cattle and horses and some chicken.

Sydney Cove sailed from Calcutta on 10 November 1796 with a crew of fifty under the command of Captain Guy Hamilton who had been retained by the new owners. The First Mate was Hugh Thompson and William Clark, a nephew of one of the new owners, was employed as Supercargo (an owner’s representative responsible for the cargo and its sale). The three other Europeans were the Second Mate Leishman, the Carpenter Thompson and John Bennet (possibly Sailmaker) and there were 44 Bengali sailors, commonly known as Lascars.

This was a lengthy voyage with course made through the East Indies around the west coast of New Holland and then south of Van Diemen’s Land before heading north up the east coast of New South Wales. Meeting heavy weather on her passage around the southwest of New Holland she sprang a leak, resulting in her pumps being manned continuously. On 9 February 1797 with the holds filling with water and when in danger of sinking the stricken vessel was safely beached at Preservation Island in the Furneaux Group northeast of Van Diemen’s Land. While the grounding was safely executed and there were no fatalities, the Second Mate had already fallen from aloft to his death, and three of the Lascars had perished in the cold and harsh conditions.

The survivors salvaged what they could of the precious cargo and brought it ashore. The rum was ferried to nearby Rum Island so as to be out of reach of her crew. Using ship timbers, a temporary shelter was made ashore. Being completely cut off from the known world with no hope of rescue a decision was made to take the ship’s longboat to reach help at the nearest settlement at Port Jackson.

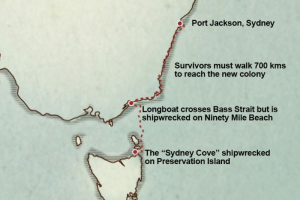

The longboat was repaired by the ship’s carpenter and on 28 February under command of First Mate Hugh Thompson with two other Europeans and 13 of the fittest Lascars, the longboat set off across what is now known as Bass Strait for Port Jackson, some 400 nautical miles (740 km) distant. Fortune was not with the brave and in attempting to land on Ninety Mile Beach (in Southeast Victoria) on 2 March the longboat was wrecked. After resting and salvaging some provisions, on 15 March they set out on an epic walk along the shore to Sydney Cove, still some 600 km distant.

They took some rice with them and with seafood this was their main form of nourishment. They had to ford several rivers and streams and were obliged to build improvised rafts to cross the larger rivers; on one occasion they were ferried across in canoes paddled by friendly natives.

They had minimal weapons of one gun and two pistols and at one stage were harassed by an armed party of about 50 natives. Many Aboriginal people they encountered were friendly but others not so and one of their party was killed during these encounters, but most perished through fatigue and lack of food. On 15 May, with their strength nearly at an end they had reached a small cove 14 miles south of Botany Bay. Now there were only three survivors: William Clark, a sailor John Bennet and one Lascar. Suddenly they saw a fishing boat and were able to signal it and at last they were in safe hands and taken to Sydney Cove where they arrived on 16 May 1797, completing their journey in 77 days.

After the longboat had departed the only European left on Preservation Island was Captain Hamilton. The other survivors were 28 Lascars. Before their rescue three Lascars were to die on the Island. They mainly survived on a diet of kangaroo meat and seabirds; a cow had been left on the island but she died. A mare on the island survived and was later trans-shipped to Sydney aboard the Francis.

Governor Hunter treated them kindly and using the limited resources of the settlement a rescue mission was soon mounted using the colonial schooner Francis and the small sloop Eliza. They sailed on 30 May to save the people and salvage the cargo on Preservation Island. Both ships reached the island on 8 June but owing to heavy seas were unable to land boats until two days later. Having loaded both vessels with the survivors and as much cargo as possible the two ships sailed for Port Jackson on 21 June. As much cargo remained, five of Captain Hamilton’s men volunteered to remain behind to care for the cargo until he could return with another ship.

On the return voyage tragedy again struck and the small Eliza was wrecked. Her crew of six men plus eight she had rescued from Sydney Cove perished. However Francis returned safely to Port Jackson with Captain Hamilton and 15 Lascars. In December 1797 and February 1798 Francis made two further voyages to the wreck site to salvage cargo. Matthew Flinders was aboard on the final voyage and made a survey of the islands. All the goods recovered fetched enormous prices which were sold for the benefit of the underwriters. At the same time George Bass was making his famous whaleboat voyage down the south coast towards the strait that would later bear his name. He was also intent on reaching the wreck site to replenish his provisions but was driven back by rough weather.

Important features of this disastrous voyage were taken from the observations of her Master who had remained behind on Preservation Island taking care of his depleted ship’s company. He reported that a strong south-westerly swell and tides suggested that a strait existed between Van Diemen’s Land and the mainland. He also observed colonies of seals and soon afterwards seal hunters were active in this area and trading through Campbell & Company. William Clark noted significant amounts of coal in the cliffs in what is now known as Coalcliff near Wollongong. Clark and party had used samples of the coal in helping sustain a camp fire. Showing how near and yet so far some of the survivors were from rescue, in a later investigation of the coastline by George Bass discovered the skeletal remains of the Mate (Thompson) and the Carpenter (also named Thompson) near Coalcliff. The sailor/explorers proved that a land route was possible between Sydney and what now is Victoria.

In September 1797 William Clark and some of the other survivors made their way back to Calcutta to report on the loss of the Sydney Cove,departing in the ship Britannia.The loss of the Sydney Cove did not deter the agency of Campbell & Clark. They acquired another vessel, a 300 ton scow, and renamed her Hunter, after the NSW Governor. Robert Campbell, the younger brother of the senior partner of the agency, accompanied the ship to wind up the affairs of the Sydney Coveand sell the Hunter’scargo. The new ship arrived in Sydney on 10 June 1798. A few days later, having done his duty, Captain Guy Hamilton died. David Collins, the Provost Marshal, in his account of the First Settlement says: He (Hamilton) never recovered from the distress and hardship which he suffered on the loss of his ship, and died exceedingly regretted by all who had the pleasure of his acquaintance.

In 1977 divers discovered the wreck of Sydney Covelying partly covered by sand in about 3 to 6 meters of water. Artefacts and some timbers are now displayed at the Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery in Launceston. In later times further archaeological excavations have revealed the camp sites on Preservation Island used by the survivors.

Possibly demonstrating the power of our diverse maritime history, a version of this story was recently re-told by a young Australian- Indian actress over four very chilly nights at Sydney’s Campbells Cove during the popular June 2017 ‘Vivid’ Festival of Light celebrations.