- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, Ship histories and stories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Cerberus

- Publication

- June 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By John McGrath

Given that the front cover of this magazine depicts a recent postage stamp with a magnificent image of HMVS Cerberus, this story by one of our contributors from Portsmouth in England is most welcome.

HMS Royal George and HMVS Cerberus

These were two very different ships from either side of the divide between wind powered, wooden warships with armament in broadsides, and ships which were steam powered, built of iron or steel and armed with turrets. Yet, surprisingly, there is a link not in technology but in people. The story began in 1756 at Woolwich Dockyard on the River Thames and seemingly ended in 1924 when a scrapped vessel was sunk as a breakwater at Half Moon Bay in the far distant Australian state of Victoria.

HMS Royal George

A ship of 100 guns, when she was launched in 1756, HMS Royal George was, for a while, the largest warship in the world. The apogee of her service came at the Battle of Quiberon Bay, 20 November 1759, when she was wearing the flag of Admiral Sir Edward Hawke. The French admiral, Conflans, attempted to avoid battle by escaping among the notoriously treacherous shallows and currents of Quiberon Bay but, despite having inadequate charts, Hawke decided to follow him in and give battle. At the beginning of the pursuit the sailing master of Royal George warned his Admiral of the risks he was taking, to which Hawke replied: ‘You have done your duty by showing the danger’. Despite these hazards and the effects of the storm that broke, Hawke obtained a stunning victory and caused the French to abandon their plans to invade Britain.

By 1782 the ship had seen hard service and was overdue for a major refit. However, there was a pressing need to send relief to Gibraltar, which had been under siege by the Spanish since 1779. So Royal George sailed up from Plymouth to Portsmouth and anchored at Spithead. She wore the flag of Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt, one of the subordinate flag officers in the fleet commanded by Admiral Richard (Black Dick) Howe.

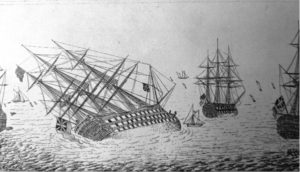

On the morning of 29 August she was in the final stages of preparations for her departure. She was careened to port to repair a drain; Admiral Kempenfelt and all the ship’s company, except the Royal Marines, were aboard as were many dockyard workers, traders, families and friends of the crew, and prostitutes. There was a lighter secured to her port side disembarking barrels of rum. Two appeals by the carpenter, Thomas Williams, to the officer of the watch, Lieutenant Hollingberry, for permission to right the ship were dismissed so Williams went directly to the Captain, Martin Waghorn, who agreed to right the ship. Too late: at about 0930, before the orders could be given, she rolled onto her port beam and sank.

She sank very quickly and, despite being in a major anchorage crowded with boats, only 255 people survived. Among them were Waghorn and Hollingberry. Kempenfelt could not escape from his cabin because the door was jammed and Waghorn’s son, also Martin, perished as well. The number who died is unknown but usually accepted to be over 800 and, possibly, in excess of 1,000.

The subsequent court martials of Waghorn, Hollingberry and the other survivors acquitted them and blamed the rotten state of the ship. Because it was sunk in shallow water, various salvage attempts started immediately and some cannons and timber were recovered. One scheme to move her using the lift generated by the tides could have succeeded had it not been frustrated by bad weather and lack of co-operation from the dockyard. This raised the suspicions of a watching journalist, Sir John Barrow, who concluded that the dockyard did not want her raised because it would have proved the verdict of the court martial. He summed it up: ‘May we not add on this occasion – one murder makes a villain – nine hundred a Navy Board’.

Charles William Pasley

With the wreck posing a serious navigation hazard in a main fleet anchorage and the prospects of money to be made from the recovered materials, further salvage attempts took place, often using novel techniques. In 1784, John Spalding recovered some more guns and other material using his improved diving bell. Then things went quiet until 1834-1836 when two brothers, John and Charles Deane, used their newly invented air-supplied diving suit in a successful campaign that saw them salvage twenty-nine cannons and many other items from the wreck.

With salvage work now uneconomic, Colonel Charles William Pasley, Royal Engineers, moved on to the site in 1839 with the aim of clearing the navigational hazard by blowing up the remains of the wreck. Today the use of explosives underwater is commonplace but Pasley was breaking new ground. First he had to make the charge waterproof. This he did by covering oak cylinders containing the gunpowder in lead. He then used the newly developed Daniell cells to provide an electric current to ignite the charges. Several trials were made using small charges in order to iron out teething problems and then on Monday, 23 September 1839 a cylinder containing just over a ton of gunpowder was lowered on to the starboard side of the wreck and at 1405 the charge was ignited. The resulting explosion caused a column of water to rise, which Pasley described as ‘like a huge hay-cock, in height about 30 feet above the surface’.

Submarine explosion clearing wreck of Royal George, from a painting by Lt R. S. Thomas RN

Work continued until the site was declared clear in 1842, by which time another 30 guns and much other material had been recovered. In 1841 Pasley was promoted to Major-General. In 1844, he also cleared the wreck of HMS Edgar, destroyed at Spithead on 15 October 1711 by an explosion in which all on board died. Pasley was an innovator; not only was he early to develop the use of explosives underwater, but he also introduced the buddy system into diving, still in use today. He was awarded the KCB in 1846, promoted to Lieutenant-General in 1851 and to General in 1860. He died on 19 April in the following year.

Charles Pasley

In 1824 his son Charles Pasley was born at Chatham. In 1843 he followed his father into the Royal Engineers, going to Canada in 1846 where his great skill in surveying was well utilised. After a spell in Bermuda it was back to Britain to work at the Great Exhibition of 1851 Two years later, still a Lieutenant, he began his fruitful association with the Australian Colony of Victoria when he was appointed as its Colonial Engineer based in Melbourne, being promotedto Captain shortly thereafter. He was also the Colonial Architect and ran the Central Roads Board. When riots broke out at the Ballarat goldfields he helped in the capture of the stockade. In 1855, with a new constitution in operation he became the Director of Public Works, and was elected to Parliament a year later. Many prominent Melbourne buildings are the result of his work. These include the Houses of Parliament, the Post Office, the Botanic Gardens and some of the main roads. He resigned in 1860 but almost immediately went on active service in the New Zealand War, being badly wounded. After convalescing in Melbourne he returned to England in 1861.

Between 1864 and 1869 he was Acting Agent-General for the Colony of Victoria. While he held this appointment, his connection with another important wreck began. Even after moving to new appointments his interest in Victoria remained and he became a Commissioner for the Melbourne International Exhibition. In 1880 he was back in the role of Victoria’s Agent-General and chairman of the Board of Advice. Awarded the CB in 1860 and promoted to Major-General a year later, he died in 1890.

HMVS Cerberus

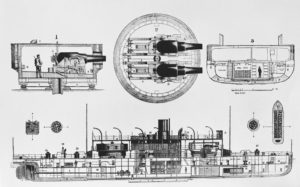

Returning to Pasley’s spell as Agent-General for Victoria, it was then that he got involved in naval ship construction. First he oversaw the equipping of the old ironclad HMVS Nelson. However, the link with a wreck came slightly later when he managed the construction and armament of the breastwork turret ship HMVS Cerberus. The turret armed ship had proved its worth on March 8–9 1862 when USS Monitor sank CSS Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads. Developing this idea, Edward Reed, the Chief Constructor of the Royal Navy, designed an ironclad warship with a central superstructure and armament mounted in centreline rotating turrets. To allow the turrets to rotate through 270 degrees, masts and sails had to be dispensed with and Cerberus was the first British warship to be solely steam powered. This meant that her operational range was short, restricting her to harbour defence duties. Built by Palmers of Jarrow-on-Tyne, she was laid down in 1867, launched in 1868, completed in 1870 and arrived in Melbourne on 9 April 1871. She was armed with two centreline mounted, twin turrets designed by Captain Cowper Phipps Cole, CB, RN. Each of these turrets held two 10 in (25.4 cm), 18 ton (20.16 tonne) rifled muzzle loading cannons, firing shells weighing 400 lb (182 kg) over a range of 4,000 yards (3,700 m). They required a crew of 33 to operate; they were trained by hand cranking and each gun had a rate of fire of approximately one round every 3 minutes.

In 1901 the Australian States federated and Cerberus was transferred to the Commonwealth Naval Force, becoming HMAS Cerberus in 1911. The Royal Australian Naval College was founded in 1913 and staff and students were appointed to Cerberus to satisfy the condition that officers on full pay hold an appointmentto one of HMA Ships in commission. By the time of the outbreak of World War I, she was already over 40 years old and suitable only for support roles, as a guard ship and munitions store ship. When Australia acquired her first six submarines in 1921, she became a depot ship under the new name HMAS Platypus II.

In 1924 over fifty years of service came to an end and she was sold for scrap but her story does not end there. After the removal of all easily recoverable scrap, she was sunk in Half Moon Bay, Port Phillip Bay in September 1926 as a breakwater. She lies very close to the shore and, as the close up shows, she remains in surprisingly good but deteriorating condition. Surely, this survivor from an important era in warship development and a World Heritage wreck is worthy of some form of preservation.

References

General Sir Charles William Pasley

Charles William Pasley – Graces Guide, accessed 24 January 2021.

Institution of Civil Engineers, Obituaries, Major-General Charles Pasley.

Major General Charles Pasley

Biography – Charles Pasley – Australian Dictionary of Biography (anu.edu.au), accessed 24 January 2021.

HMVS Cerberus, History

HMAS Cerberus (HMVS) | Royal Australian Navy, accessed 30 January 2021;

HMVS Cerberus HMVS Cerberus | Naval Historical Society of Australia (navyhistory.au), accessed 11 February 2021.

HMVS Cerberus Preservation Phase 2, Final Report, BMT Design & Technology, 01 July 2013, BMT Report Template (cerberus.com.au), accessed 11 February 2021.

HMS Royal George:

Slight, Henry, True Stories of H.M. Ship Royal George (Ryde, Isle of Wight: E. Hartnall, 1841).

0A Narrative of the Loss of the Royal George at Spithead, August 1783; etc. (Portsea: Printed and Published by S. Horsey, Sen, 14, Queen Street, Seventh Edition, 1845.